SAMURAI REINCARNATION (1981)

Amakusa Shiro resurrects other dead historical figures to overthrow the Shogunate, while Yagyū Jūbei Mitsuyoshi rises to fight him and his warriors of the dead.

Amakusa Shiro resurrects other dead historical figures to overthrow the Shogunate, while Yagyū Jūbei Mitsuyoshi rises to fight him and his warriors of the dead.

The events of Kinji Fukasaku’s highly entertaining Edo-period chanbara fantasy Samurai Reincarnation / Makai tenshô take place in the wake of the Shimabara-Amakusa Rebellion, a real piece of 17th-century Japanese history. In late-1637, a group of Catholic ronin, led by charismatic teenager Shiro Amakusa, took up the peasants’ cause in resisting the overbearing rule of the Shimabara region by its feudal daimyo.

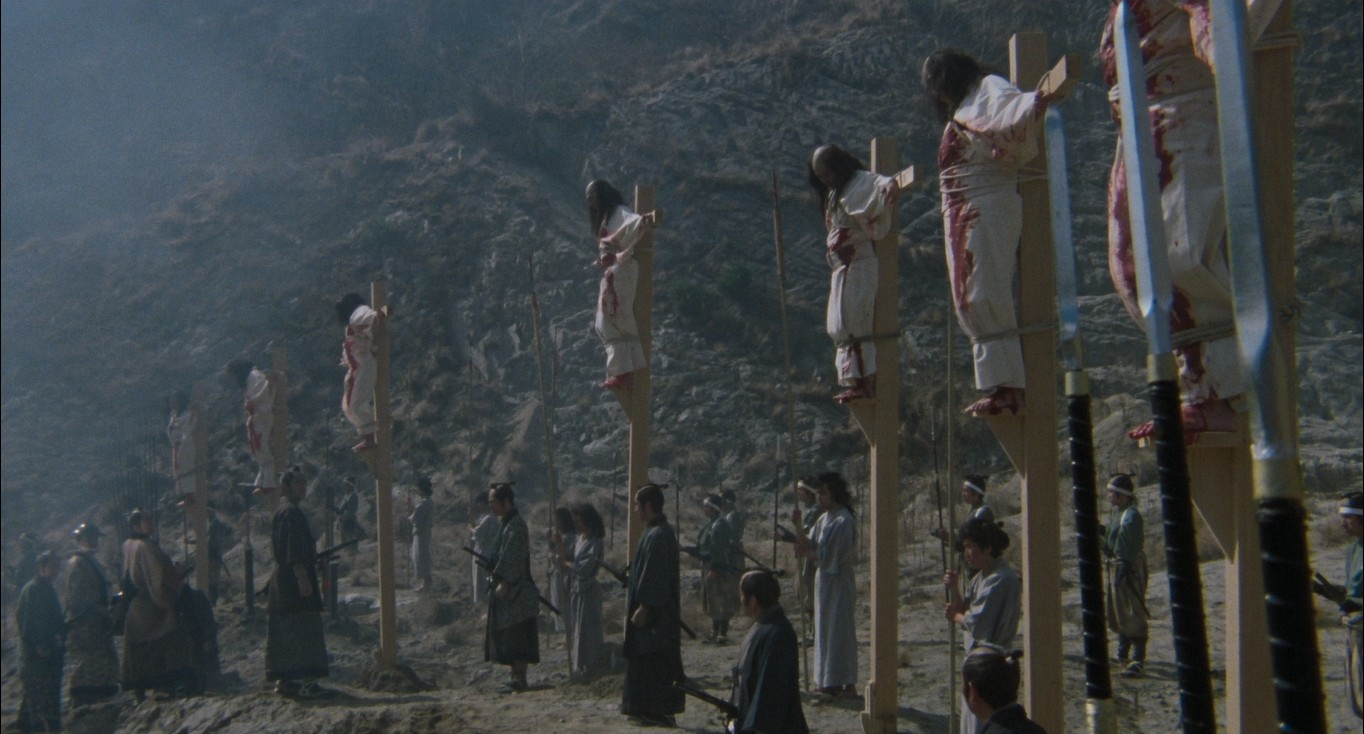

The uprising was eventually put down by the Tokugawa shogunate with the infamous massacre of 37,000 Christian rebels and peasants in mid-1638. Many had died in battle against overwhelming numbers of the Shogun’s soldiers, sent to suppress the rebellion, but it seems the majority were rounded up and executed by beheading. The daimyō, Matsukura Katsuie, enthusiastically persecuted Christians and ruled by fear—forcing troublesome peasants to wear straw overcoats so they could be easily set alight if disobedient. He was subsequently investigated and executed by the Edo Shogunate for dishonour, misrule, and cruelty.

The film opens with a kabuki performance, presumably on the massacre site and probably upon some significant anniversary. It seems the actor playing the part of a demonised Shiro Amakusa gets into the part so much that he’s possessed by the spirit of the rebel leader. A sudden storm devastates the stage, and the audience is struck down by lightning as he wanders through an echo of the past among a vast field of corpses and severed heads.

The scene is gruesome yet beautifully shot, like a combination of Hammer Horror and a New Romantic pop video. So it seems fitting when the kabuki player removes the demonic drama mask to reveal the face of Shiro (Kenji Sawada), reincarnated. Kenji Sawada was a famous pop singer at the time, often described as Japan’s answer to David Bowie, and plays Shiro with the style and charisma befitting a glam rock star. It’s been surmised David Bowie was taking notes for his performance as the Goblin King in Jim Henson’s Labyrinth (1986) as there are passing similarities!

During this arresting opening sequence, Shiro monologues to his fallen comrades and vows to avenge their deaths. He passionately denounces God and Christianity, invoking the demonic powers of Hell. The theatrics and sentiment of the sequence would be echoed in the opening of Francis Ford Coppola’s Bram Stoker’s Dracula (1982). Just like Vlad Dracula, Shiro Amakusa was a real historical figure with bloody associations, who became a romantic antihero, accruing mythic status over the centuries.

The first act then plays out like a kind of supernatural Dirty Dozen (1967), or more like a half-dozen, as Shiro collects a band of historic personages who died with troubled spirits, convincing them to return as demons to complete unfinished business or to sate unfulfilled desires. In a series of vignettes, we get a portmanteau of backstories that briefly introduce each in turn, so we know the circumstances of their deaths and the nature of the various injustices and resentments powerful enough to bring them back as the undead.

First, Shiro visits the tomb of Lady Hosokawa Gracia (Akiko Kana), a 16th-century aristocrat and Christian convert whose faith prevented her from committing seppuku to avoid being taken hostage by a rival clan during the battle of Sekigahara. Instead, she was murdered by staff, possibly on the instructions of her husband. Her death triggered events that ended the Sengoku period of warring states and established the Tokugawa shogunate, in turn leading to the comparatively stable Edo Period.

Shiro manages to draw her decaying ghost from its grave and after encouraging resentment of a God that failed to protect her from dishonourable death, appeals to her vanity and unsatisfied womanly desires. Using a very western-looking magic circle, summoning triangle, and some 1980s video effects, he manages to restore her beauty whilst instilling her new demon form with a seductive, sadistic streak.

Then we meet the aged Miyamoto Musashi (Ken Ogata), legendary samurai and 17th-century Kensei; a title only ever awarded to an undisputed master swordsman… and there can be only one. He was famously undefeated in battle, surviving shifting political allegiances as a samurai, spending time as a wondering rōnin, devising and teaching the iconic two-sword technique so well suited to cinematic portrayals. Remarkably for any active samurai, he eventually died of natural causes as an old man after spending his latter days as a hermit, painting and writing poetry in the mountains.

He’s awaiting death in his cave when Shiro and Lady Hosokawa Gracia visit him and plumb the depths of his memories for some regret. He’s sad that he chose the way of the sword over a relationship with a woman he loved but is convinced that was best for them both. The demons manage to coax an admission he could never be sure he deserved his reputation as Kensei because he never battled either Lord Yagyu or his son, Jubei, and he suspects they may’ve been able to defeat him during his twilight years. Isn’t that just typical macho samurai reasoning?! He’s tricked into dying with this admission of regret on his lips and Shiro is then able to reanimate him as a demon.

This introduces Jubei (Sonny Chiba), a popular recurring character in Japanese fiction, inspired by a renowned samurai and instructor of sword techniques for the Tokugawa Shōgunate. As a real master samurai with little known about him and long gaps in his biography, he has been repeatedly reinvented, appearing again and again on the big and small screen… I lost count at 66 titles! I suppose a western equivalent would be King Arthur or Robin Hood. Here we have the best-known eye-patch-wearing version from the Jubei Yagyu Trilogy by novelist Futaro Yamada—part of his long-running Ninpō-chō series of historical mysteries and fantasies.

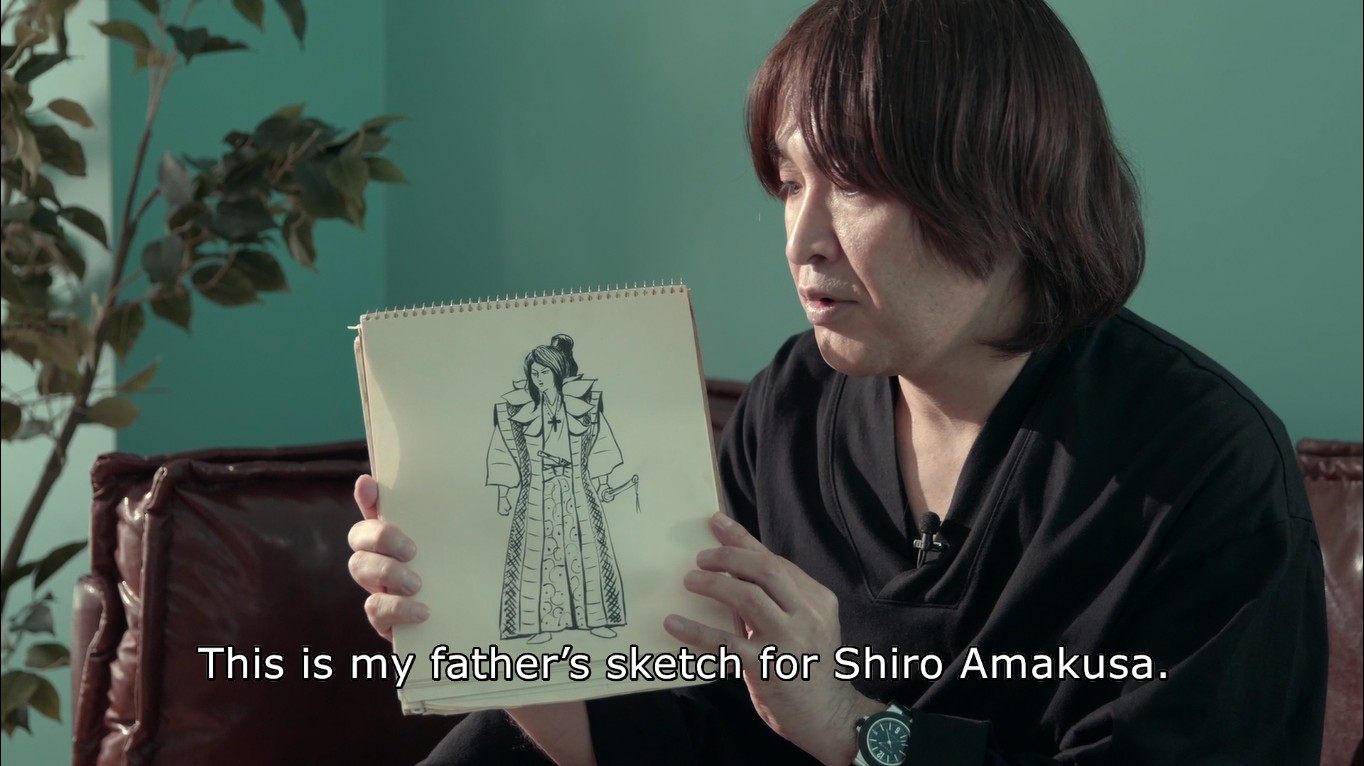

Samurai Reincarnation is a loose adaptation of the second in the trilogy, Makai Tensho (literally ‘Hell Reincarnation’), first published in 1967. In Kenji Fukasaku’s reimagining, Shiro is elevated from a minor role to replace the novel’s main antagonists, an allegiance of two necromancers, and Jubei is the central protagonist.

One of the main twists—don’t worry, I won’t give too much away—involves Jubei’s father, Lord Yagyu (Tomisaburo Wakayama), dying after battling one of the demon spirits only to be offered resurrection by Shiro so he can face his own son, whom he trained with a strict regimen, in battle. Remember, this is the great father and son team that Musashi also desires to prove himself against. Tomisaburō Wakayama was a master swordsman in real life and an iconic actor in samurai cinema after starring as Ogami, better known as Lone Wolf in Shogun Assassin (1980) and Kenji Misumi’s Lone Wolf and Cub franchise.

The showdown between father and son has added depth because there’s an echo of real life. Tomisaburō Wakayama trained Sonny Chiba in sword technique. Their fight choreography is both spectacular and realistically understated, taking place in an infernal sequence as Tokyo burns down around them.

Another big change from the novel is the introduction of the young Kirimaru (Hiroyuki Sanada), the only survivor of his village after a vicious raid by rivals. His resurrection is fuelled by a desire to avenge his family, but he manages to retain a portion of his youthful innocence as a conflicted character. He serves as a moral bridge between the demonic realm and the world of mortals, helping to keep a complex narrative cohesive.

Anyone who watches chanbara films, or has at least seen Crouching Tiger, Hidden Dragon (2000), knows the sword has a spirit and is the soul of the samurai. So, one can reason that a pure spirit may be corrupted if used against demons from beyond. So, Jubei seeks out a disgraced swordsmith (Tetsurô Tanba) known to make ‘evil blades’ inspired by Sengo Muramasa, the real maker of swords for the Tokugawa shogunate. His swords were said to be so well-made that using them became addictive and the wielder would become consumed by blood lust, craving the aesthetics of dismemberment.

The swords were blamed for inspiring several historic massacres and murder-suicides and, as with the folklore surrounding metalsmiths the world over, Muramasa was credited with magical powers that stemmed from devils. Tetsurô Tanba was already a veteran actor, best known outside Japan for his appearance as Tiger Tanaka in You Only Live Twice (1967), but also appeared in several key chanbara such as Masaki Kobayashi’s Harakiri (1962) and Hideo Gosha’s Three Outlaw Samurai (1964).

Nowadays, director Kinji Fukasaku is best known for his final film, Battle Royale (2000) which, along with Ryûhei Kitamura’s Versus (2000), is often cited as triggering the ‘Asia Extreme’ trend and revitalising Japanese cinema’s international appeal. However, that wasn’t the first time he’d shaken up Japan’s genre cinema. His first film had been the yakuza crime thriller Drifting Detective: Tragedy in the Red Valley (1961) starring Sonny Chiba.

Fukasaku was soon indelibly associated with Japanese gangster films, but perhaps his brutal yakuza pentalogy, Battles Without Honor and Humanity (1973-74) and follow-up triptych, New Battles Without Honor and Humanity (1974-76), are his most significant legacy. Portraying Yakuza as amoral thugs their lack of romanticism and a gritty, almost verité style impacted pretty much all Japanese gangster movies that followed effectively trapping the director in the genre for years.

He also made a smattering of war films, notably co-directing, with Toshio Masuda and Akira Kurosawa, the Japanese sequences for Tora! Tora! Tora! (1970). There were a couple of comedies starring Sonny Chiba in the title role as the Hep Cat in the Funky Hat (1961) and its sequel, The 20,000,000 Yen Arm (1961). He first dabbled in science fiction with The Green Slime (1968) and was in the director’s chair for Virus (1980), a post-apocalyptic bio-thriller again starring Sonny Chiba. At the time, it was the highest-budget film to have been made in Japan.

Clearly, he could turn his hand to a variety of genres and, having made only one samurai film before, The Yagyu Clan Conspiracy (1978), he was nevertheless bold enough to fuse chanbara, period drama, supernatural fantasy, Japanese ghost story, and Hammeresque gothic horror in Samurai Reincarnation.

The longevity of any genre always comes down to innovation, usually brought about by inventive fusing of aspects from other genres. Although there had already been minglings of chanbara and supernatural aspects—such as Kwaidan (1964), The Sword of Doom (1966), and seven of the Lone Wolf and Cub movies—this was far less subtle and brought in western occultism. Shiro even invokes powers and demons from the pantheon of qabalistic magic and Beelzebub is called upon.

As well as making this more accessible for a world market more familiar with such imagery, it also highlights one of the film’s subtexts exploring the contrast, and philosophical conflicts, between East and West. Despite this, the overseas reception was lukewarm, and no major distribution was secured ahead of a VHS home entertainment release that unsympathetically chopped the duration down to just 88-minutes with utter disregard for key scenes, effectively rendering the plot unfollowable.

It performed very well in Japan, winning two major Japanese Academy Awards—‘Best Newcomer’ for Hiroyuki Sanada and ‘Best Art Direction’ for Tokumichi Igawa and Yoshikazu Sano—and rekindled interest in the popular novels of Futaro Yamada and informed subsequent adaptations on stage and screen. There were two loosely related sequels, Reborn from Hell: Samurai Armageddon and Reborn From Hell: Jubei’s Revenge, both directed by Kazumasa Shirai (his only films) and released straight to video in 1996. Ninja Resurrection (1998) was the pilot for an abortive anime series version. There was a 2003 remake, directed by Hideyuki Hirayama which I haven’t viewed but was reputedly let down by its poor CGI visuals.

JAPAN | 1981 | 122 MINUTES | 1.85:1 | COLOUR | JAPANESE

Long overdue for reappraisal, so kudos to Eureka! Entertainment for releasing this new 2K restoration from original film elements as the latest addition to their ever-expanding ‘Master of Cinema’ imprint for this 1080p presentation on Blu-ray.

director: Kinji Fukasaku.

writer: Kinji Fukasaku & Tatsuo Nogami (based on the novel by Futaro Yamada).

starring: Sonny Chiba, Kenji Sawada, Tomisaburo Wakayama, Ken Ogata, Akiko Kana, Hideo Murota, Hiroyuki Sanada & Tetsuro Tamba.