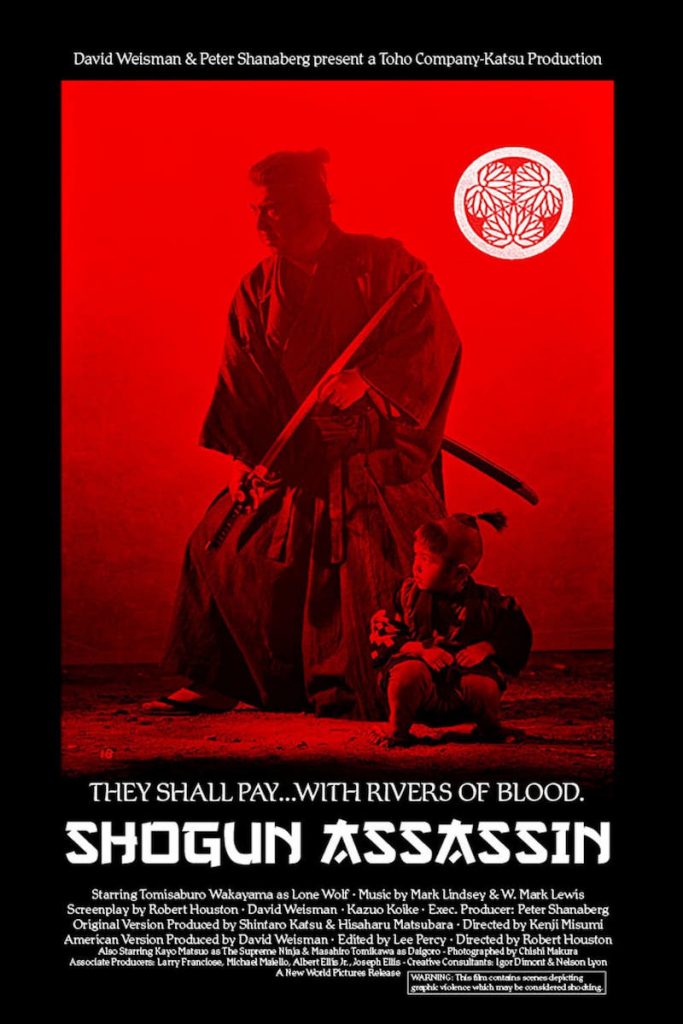

SHOGUN ASSASSIN (1980)

When the wife of the Shogun's Decapitator is murdered and he's ordered to commit suicide by the paranoid Shogun, he and his four-year-old son escape and become assassins for hire...

When the wife of the Shogun's Decapitator is murdered and he's ordered to commit suicide by the paranoid Shogun, he and his four-year-old son escape and become assassins for hire...

Shogun Assassin is an exceptional movie. It’s a beautiful samurai film and a cult classic infamous for its widespread ban during the 1980s. It’s still referred to as one of that era’s infamous ‘video nasties’, but it’s so much more than that! In fact, with Shogun Assassin, you’re getting three films for the price of one, and I can’t think of another example of such an approach. At least none as successfully executed.

Shogun Assassin is certainly a film in its own right, but apart from a few minutes of stock footage, it was made by cutting two existing movies together. The resulting hybrid, perhaps not greater than the sum of its parts, is at least as rewarding and eminently re-watchable. This really shouldn’t be so! Isn’t it a cardinal sin to re-dub and re-cut the work of another director to such an extent as to change the narrative? Especially when that director is the great Kenji Misumi. But that’s what Robert Houston and David Weisman did with the first two films in the Lone Wolf and Cub franchise.

Shogun Assassin was the ‘directorial’ debut of Robert Houston, but it was more like the editorial equivalent of a remix because there was no actual production involved. He rewrote and cut together existing footage. Houston had made his acting debut in Wes Craven’s The Hills Have Eyes (1977) and this whetted his appetite for indie filmmaking, so he Houston teamed up with artist David Weisman as co-producer and co-writer.

Weisman came from an interesting background and his route into film was unconventional. He’d trained in graphics and designed the poster and marketing materials for Federico Fellini’s 8½ (1963) and also the titles for Otto Preminger’s Hurry Sundown (1967). A protégé of the Andy Warhol Film Factory, he also co-directed Ciao! Manhattan (1972), in which Warhol’s muse Edie Sedgwick played Susan Superstar, a fictionalised version of herself. Appropriating the films of another director from another foreign culture probably didn’t seem all that weird to him!

It was an experiment that shouldn’t have paid-off at all. But it did. Maybe I’d feel differently had I already been a fan of the original films but, for me, like so many others, this was my introduction to what I now call ‘the dishevelled samurai genre’—a sub-genre of chambara which Kenji Misumi played no small part in defining. He directed The Tale of Zatōichi (1962), the first of the Zatōichi movies, plus a further five of its 25 sequels. He also helmed a couple of episodes for the long-running namesake TV series (1974-79). Featuring the titular blind swordsman. Zatōichi became one of the most popular and longest-running franchises in Japan.

Not content with just the one influential chambara franchise, Misumi also created the legendary Lone Wolf and Cub series of films, beginning with Sword of Vengeance (1972), based on the popular graphic novels by Kazuo Koike and illustrated by manga artist Goseki Kojima.

The manga were already a huge success in Japan, serialised in Weekly Manga Action Magazine and then running for 28 volumes, between 1970-76, totalling around 8,700 pages of what was effectively a readymade storyboard. So, Kenji Misumi’s movies were fairly faithful realisations of the saga of Ogami Ittō, a rogue samurai (or ronin) who takes the road of vengeance as a single parent…

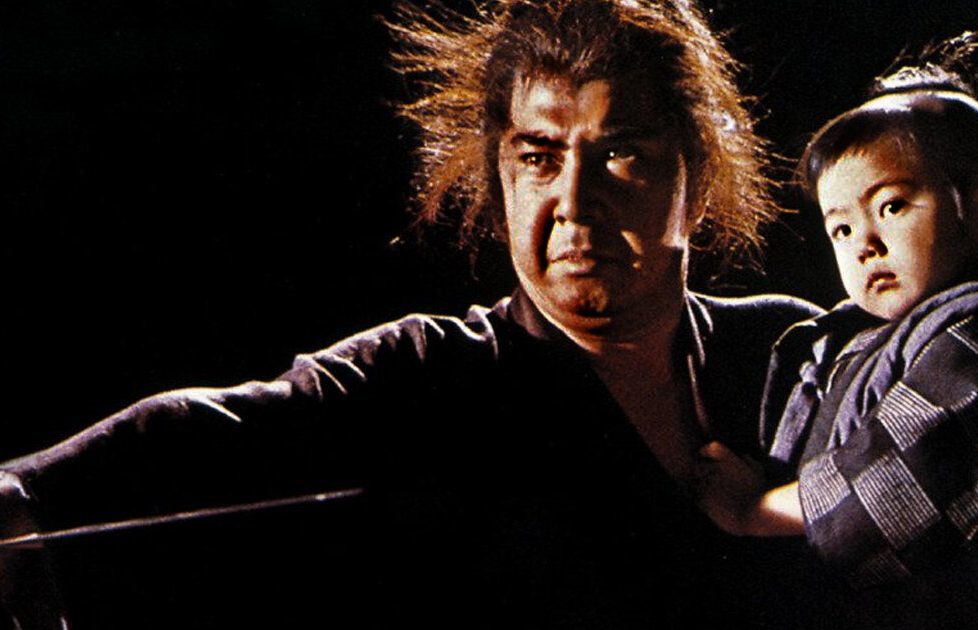

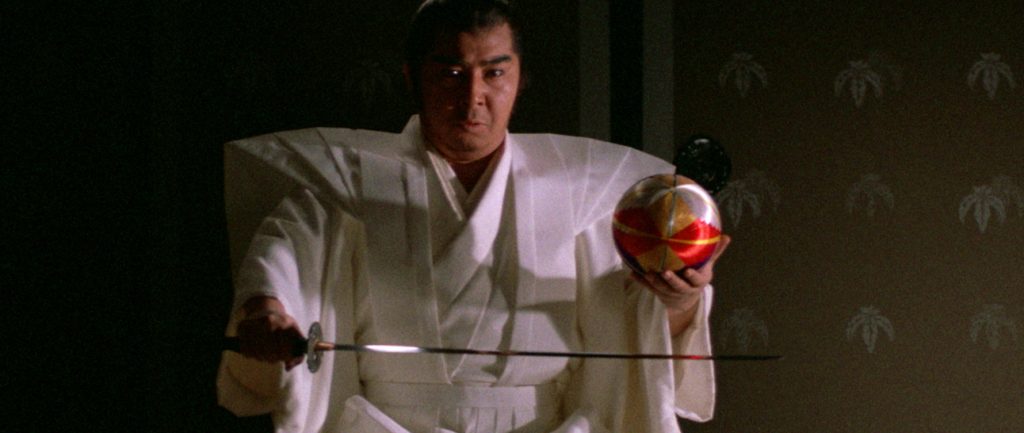

In the original six films (1972-76), Ogami (Tomisaburō Wakayama) is the highest-ranking samurai in an Edo era shogunate, framed by the rival Yagyu clan, who want to infiltrate the court of his master. As part of the plot, they murder his wife, Azami (Keiko Fujita), and he’s forced to flee with his three-year-old son Daigorō (Akihiro Tomikawa).

Not only is he pursued by Yagyu clan assassins, but his former master also believes him to be a traitor and puts a bounty on his head. So Ogami must live by his wits and his blade, all while raising his son and instructing him in the ways of combat, while biding his time until opportunities for vengeance come along.

The stories, of the manga and films, were inspired by tales told of Miyamoto Musashi—a real historical personage who evolved into a folk hero. He wasn’t just any samurai, he was the Kensei of the early 17th-century. The title of Kensei was only held by the greatest living swordsman at any one time.

Musashi became famous for his unconventional two-sword technique which he developed and taught. For periods of his life, he was a wandering, masterless samurai with plenty of adversaries. During these times, he rarely took a bath and, if ever he did, he would keep his hand on his sword, even when in the tub. He was known to look like a wild man as he never felt at ease enough to drop his guard for personal care, so his hair grew and was only combed rarely.

He would live like this until all of his outstanding enemies were dealt with. Then, he’d begin his life on the road again, travelling from village to village as a sword for hire and samurai teacher. For the last portion of his life, he became a hermit, living in a cave where he concentrated on his art and writing.

He authored two important books, too. Go Rin No Sho / The Book of Five Rings was an instructional manual on the way of the samurai, swordsmanship and battle strategy. Dokkōdō / The Solitary Path was a philosophical work about the importance of finding and following one’s own path through a lonely life. He remained undefeated and, rarely for an active samurai, died of old age.

Musashi was clearly the inspiration for Ogami Ittō. Tomisaburô Wakayama’s deportment in the lead role is so impressively authentic, I long assumed he’d been to samurai school! I wasn’t far wrong… he came from an acting background, both his parents being stars of Kabuki theatre, in which he began his career before showing a natural prowess in martial arts.

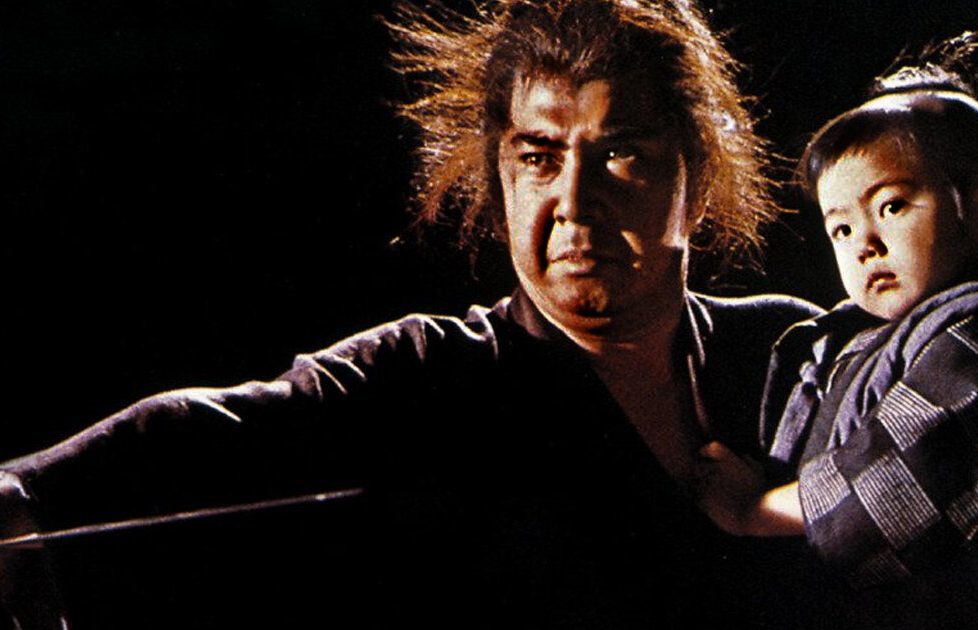

He became a judo instructor and was skilled in Shaolin-style kung fu, Bōjutsu (combat using a staff) and Kendo (based on the samurai ‘way of the sword’). He also trained in the advanced technique of Iaidō which is brilliantly demonstrated in Shogun Assassin. This is a focus on smoothly combining a sequence of moves where the wielder draws the sword, cuts an opponent, flicks the blood from the blade and returns it to its sheath, ideally completing the fluid gesture before the victim falls.

Shogun Assassin set the bar for what western audiences expected from a samurai movie and opened the mainstream market for Japanese swordplay films. It followed-on nicely from the kung fu craze sparked by Bruce Lee films like Enter the Dragon (1973)… and there had also been the popular TV series Kung Fu (1972-75), which literally westernised the genre. I still have the bubble gum cards!

So, kung fu was all the rage for the second half of the 1970s. Carl Douglas even sung about its prevalence, which was a little bit frightening, but the craze was cooling off when James Clavell’s Shōgun (1980) shifted emphasis from Chinese martial arts toward Japanese historical drama.

Shōgun, the NBC mini-series, was by far their most successful and attracted the second largest audience in US TV history, after Roots (1977). Clavell’s novel became the year’s bestselling book. So, the time was ripe and, when Houston and Weisman were trying to think of a snappy title instead of Kozure Ôkami: Sanzu no Kawa no Ubaguruma, which directly translates as Wolf with a Child: a Perambulator of the River of Sanzu. It didn’t take too long to settle on Shogun Assassin.

They attempted to keep the film self-contained and, to that end, rewrote the central narrative. Their take simplifies the story and dispenses with the plot involving the rival clan. The opening 10-minutes of Shogun Assassin set up the backstory and are a condensed edit of events from the first Lone Wolf film, Sword of Vengeance.

Daigorō, excellently voiced by Gibran Evans, narrates an alternative version in which the shogun has become insane, or as he puts it, “people said his brain was infected by demons and that he was rotting with evil…” The white-haired leader of the Yagyu clan (Tokio Oki) is presented here as the mad shogun. Incidentally, it was Gibran’s father Jim Evans who provided the titles and original promotional art, including the striking poster illustration depicting Ogami wielding two swords.

The remainder of the film’s made up of a tightened and re-ordered cut of the second Lone Wolf instalment, now known as Babycart at the River Styx (1972), in which Ogami and Daigorō take on a succession of bounty hunters and would-be assassins. One startling difference, that truly alters the mood, is the heavy synth score that’s very much of the ’80s. It was a collaborative effort between W. Michael Lewis and Mark Lindsay which ended up rather reminiscent of John Carpenter films of the decade. Robert Houston also contributed the orchestral overture.

More than anything else, it’s really the sound of Shogun Assassin that makes it a film in its own right. Much of the story is told as voiceover, and the dubbed dialogue is minimal. The small English-language voice cast do a brilliant job, creating a singular quality that differs from the raw Kenji Misumi movies.

The main narrative changes relate to a thread concerning the subtle, unrequited romantic frisson between Ogami and the supreme ninja (Kayo Matsuo). For me, the pacing seems quicker than the original, though there’s really little difference in most of the scenes. Lee Percy did much of the hands-on editing. He’d go on to work with Weisman again on his Academy Award-winning Kiss of the Spiderwoman (1985) the same year he also edited Stuart Gordon’s Re-Animator (1985), followed by From Beyond (1986).

The fights remain fluid and functional and are certainly the main attraction. The brutality of the plentiful gore-gushing dismemberments and decapitations is balanced by their balletic beauty. Despite their artistry, the battle sequences were just too bloody for western audiences, new to the chanbara style, to handle.

The most gruesome scene, possibly what clinched its 10-year ban, is when the team of lady ninjas take on the shogunate’s strongest man. The sequence is played out in silence except for the pattering of slippers, the whoosh of blades and the wet thuds of body parts hitting the floor as the unfortunate victim is taken apart. One feels for the guy—he was outnumbered and his mates just sat there and watched! The demonstration shows that ninjas will be more effective at bringing down the rogue decapitator than regular soldiers because they won’t adhere to the code of honour code kept by aspiring samurai.

There’s also a scene that begins as if rape is intended, but in a matter of seconds it’s pretty clear that’s not the case. There’s certainly an aspect of gendered power-play involved, but the intention is an honourable one, to save the life of the woman and others. It’s a key scene in developing the dynamics between three main characters.

There’s also some outrageous bloodletting in the ultimate confrontation between Ogami and the notorious Masters of Death (Minoru Ôki, Shôgen Nitta and Shin Kishida). They finally face-off in a stark, colour-drained desert, culminating in some quotable dialogue delivered during a poetic death scene…

It’s a bit weird to talk about the different cuts of the print when the film itself is a ‘collage’ of two older films combined into a third that’s not the same as either. As far as I know, the full version is around 85-minutes in duration, passed by the BBFC as an X certificate in 1981, with just a few seconds shaved off some scenes. This is the edit released by Vipco, the home video label infamous for taking advantage of a legal loophole that allowed video releases to slip past the censors a few years before the 1984 Video Recordings Act came into force. This was the illicit edit that so impressed me before the film was banned and withdrawn from circulation in 1983, ensuring it became a much sought after cult classic, widely shared as bootlegged copies.

I imagine it was this version that left its mark on the young batch of future filmmakers that have cited it as a huge influence. Frank Miller is a known fan and also provided the cover art for the English language editions of the original comics, published by Dark Horse in the US. Quentin Tarantino based the sword fights in his Kill Bill (2003-04) duology on those in Shogun Assassin, and included an explicit nod when the Bride’s four-year-old daughter requests it for her ‘sleepy time’ film.

A rather poor-quality print was re-submitted in 1992, with around three minutes missing, and granted an 18 certificate. Later, in 1999 a DVD version was released on the Horror Video label, promoted as the ‘uncut version’ but with only about 30-seconds restored. It was also billed as a ‘widescreen edition’ but, far as I could tell, is just the old 4:3 format, weirdly cropped, stretched and disconcertingly distorted, not to mention terribly duplicated. Unfortunately, that’s the only version I now own as my original Vipco VHS succumbed to some kind of white mould years ago.

A restored and remastered version was put out by AnimEigo for the US market in 2006, but deleted soon afterwards. That edit was rebuilt from the ground up, using original material from the first two Lone Wolf films in their uncompressed 2.35:1 anamorphic form. Then the visuals were synced, edit for edit, to the original. Some of the additional stock footage used for establishing shots remained in poorer quality and I’m not sure which print they used as their template. I’m guessing the 1980 cinematic version released in the US by New World Pictures. In 2017, the original six-film Lone Wolf and Cub sequence was remastered and released as a Blu-ray box set by Criterion.

Darren Aronofsky has been talking about making his own version of Shogun Assassin for a while. As has Justin Lin (Star Trek Beyond), who seems the better match of the two. Steven Paul, who produced the Ghost in the Shell (2017) live-action remake, acquired the rights in 2016 and began putting together a production package…

Most recently, Disney borrowed heavily from the plotline for a central thread in their Disney+ main attraction The Mandalorian, set in the Star Wars universe. The similarity between the titular character caring for a ‘yoda-ling’ in a hovering baby cart, beset by bounty hunters is no coincidence.

Even now, 40 years later, it’s difficult to believe that a remake will ever capture the distinctive vibe of the ‘original’ 1980s re-hash, and certainly won’t muster that nostalgic appeal for those who saw it in their formative years, when its whole stylistic approach seemed so bloody fresh. Accept no substitutes!

JAPAN • USA | 1980 | 85 MINUTES | 2.35:1 | COLOUR | ENGLISH

directors: Robert Houston & Kenji Misumi.

writers: Robert Houston, David Weisman & Kazuo Koine (based on ‘Lone Wolf and Cub’ by Kazuo Koike & Goseki Kojima).

starring: Tomisaburo Wakayama, Kayo Mautso, Akiji Kobayashi, Minoru Ôki, Shôgen Nitta, Shin Kishida & Tokio Oki.