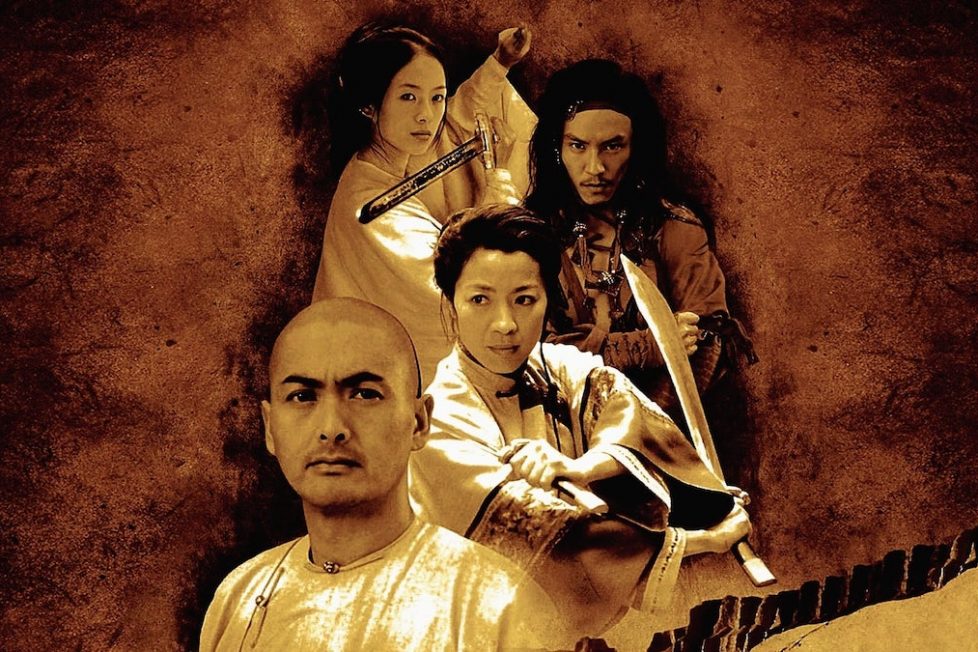

CROUCHING TIGER, HIDDEN DRAGON (2000)

A young Chinese warrior steals a sword from a famed swordsman and then escapes into a world of romantic adventure with a mysterious man in the frontier of the nation.

A young Chinese warrior steals a sword from a famed swordsman and then escapes into a world of romantic adventure with a mysterious man in the frontier of the nation.

Much has been said about Crouching Tiger, Hidden Dragon’s role in the popularisation of wuxia films in the early 2000s, and its legacy since. The surprise hit, with dialogue in Mandarin and subtitles in English, triggered a slew of wuxia films such as Hero (2003), House of Flying Daggers (2004), and Curse of the Golden Flower (2006)—all directed by Zhang Yimou.

What is this film’s legacy? In retrospect, the interesting thing isn’t the mainstream introduction of the fantasy wuxia genre. It’s clear, especially to western audiences that hadn’t grown up with them, that this wasn’t realistic. There were heroes and heroines climbing up walls and practicing Qing Gong on bamboo forests while fighting!

The fascinating thing is how this period drama (set during the Qing Dynasty) was also a work of fantasy, besides the gravity-defying fights. Taiwanese filmmaker Ang Lee made this as ‘China of the imagination’, which meant that, as a depiction of Chinese culture, large swathes are a mix of different period eras, making it confusing to period drama experts. The fact Lee’s fantastical vision, only representing Chinese culture, led to a huge influx of wuxia films, is ironic now. In 2020, audiences have come to expect more from films and are aware of how stereotypes can be damaging.

Even in 2000, however, there was confusion amongst Chinese audiences that resulted in Crouching Tiger, Hidden Dragon tanking at the Chinese box office. Across the Pacific, it became the highest-grossing foreign-language film at the US box office, and then clinched a record-breaking four wins at the 73rd Academy Awards. It’s clear to say it was more popular with western audiences than Chinese ones, and has remained that way even two decades later.

The story, popular with audiences for featuring two strong female heroines, might have been a part of what made Crouching Tiger a surprise hit—but considering it came out only two years after Disney’s Mulan (1998), there should’ve been more films capitalising on the idea of a strong female Chinese heroine. You can’t say Ang Lee didn’t do a shrewd job crafting this film to appeal to Hollywood.

It’s therefore confusing for me to watch Crouching Tiger, as my understanding of Mandarin, plus familiarity with wuxia, makes me sensitive to the mistakes western audiences easily overlooked. For one, the dialogue veers wildly between traditional language (idioms, period-accurate poetry) and modern sentences—especially about love.

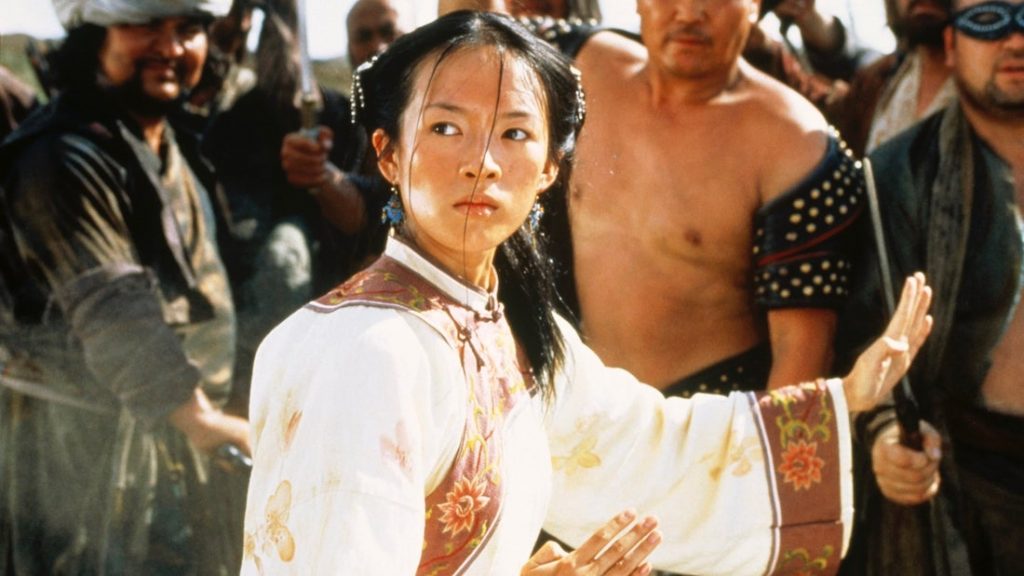

There’s also criticism in terms of the accents, as only Zhang Ziyi was born and bred in China. Chow Yun-fat was raised in Hong Kong (where Cantonese is the norm) and Michelle Yeoh is from Malaysia and grew up speaking English and Malay. Chang Chen is Taiwanese. This might seem unimportant to western audiences, but it’s akin to watching a film set in London while most of the main cast has Yorkshire and other regional accents. Does it matter that much? Well, in a film with a lot of talking, it does. Michelle Yeoh had to learn her dialogue phonetically, while Chow Yun-fat has said he did 28 takes on the first day just to correct his accent.

You can hear the strained pronunciation and the effort expended in speaking coherently throughout Crouching Tiger. At one point, I had to just rely on people’s faces and read the subtitles, just as western audiences did, in order to enjoy the performances. And enjoy I did, because the actors are sublime, using their faces to emote what they might’ve failed to verbalise emotionally. In 2020, we expect extra time to have been spent on dialect coaching, but for 2000 it’s pretty darn good.

Zhang Ziyi, especially, in one of her first few roles, is transcendent, using her ample screen time to lay bare the nuances of the youthful, arrogant, and yet demure Jen. She’s the string that holds the story together and keeps it chugging along, even until the end. Original choice Shu Qi (who turned it down) would have been too outwardly feisty, and it wouldn’t have played as well opposite Cheng Pei-Pei (Jade Fox), recently seen as the matchmaker in Disney’s live-action Mulan (2020).

Another universally-acclaimed segment of Crouching Tiger has always been its martial arts sequences, choreographed by Yuen Woo-Ping, then well-known with western filmgoers as the genius behind The Matrix (1999) fight sequences. Honestly, as martial arts choreography goes, it doesn’t stand out amongst the long history of wuxia films, but it’s still spectacular today due to how the main cast were doing the wire-fu. This is an uncommon sight in modern action films, where stunt doubles are used liberally.

Looking back at the film 20 years later, it’s odd to think of the decades in which Asian films worked and tried so hard to appeal to Hollywood and western audiences. Even last year, when Parasite (2019) won the Academy Award for ‘Best Film’, it was hailed as a huge validation for Asian cinema with trade magazines constantly reporting on its US box office gross. This is happening while Hollywood is, conversely, trying to break the ever-growing Chinese film market.

Can we tie this development to the legacy of the fantasy wuxia Crouching Tiger, Hidden Dragon? To some extent, sure. There’s no doubt western audiences found a taste for wuxia after this film’s release. The kung fu genre had long ago come and gone in Hollywood, but here was another piece of (inaccurate) Chinese culture that could be consumed and enjoyed, only with strong female characters for a change!

However, international wuxia movies had lost their allure by the end of the decade, with the only interesting outlier being the Kung Fu Panda animated trilogy (currently still popular in China). At this point, the Chinese film market had already stepped up its own game, churning out many of their own domestic hits. So, while Crouching Tiger might have assisted in turning Hollywood’s eye toward China, it definitely didn’t create a huge boom in Chinese filmgoers.

In the end, the legacy of Crouching Tiger is one steeped in the idea of a Chinese film: with stellar Asian actors of Chinese ethnicity, showcasing a story with overt Chinese culture, it made Chinese period films cool in Hollywood. The Academy Award-winning soundtrack, composed by Tan Dun, is nothing but an ode to Chinese period dramas. That mattered a lot at the time, and has had a huge impact in increasing the appeal of China to Hollywood within the last 20 years.

In looking back, there are definitely some areas that could be improved upon, but considering the time in which this was made and its impact on world cinema, there’s no doubt Crouching Tiger, Hidden Dragon is a classic slice of film history.

TAIWAN • HONG KONG • USA • CHINA | 120 MINUTES | 2.39:1 | COLOUR | MANDARIN

director: Ang Lee.

writers: Wang Hui-ling, James Schamus & Kuo Jung Tsai (based on the book by Wang Dulu).

starring: Chow Yun-fat, Michelle Yeoh, Zhang Ziyi, Chang Chen, Sihung Lung & Cheng Pei-pei.