PINK FLAMINGOS (1972)

Notorious Baltimore criminal and underground figure Divine goes up against a sleazy married couple who make a passionate attempt to humiliate her and seize her tabloid-given title as 'The Filthiest Person Alive'.

Notorious Baltimore criminal and underground figure Divine goes up against a sleazy married couple who make a passionate attempt to humiliate her and seize her tabloid-given title as 'The Filthiest Person Alive'.

Criterion continues their restoration of John Waters’ early work with this month’s eagerly anticipated 50th anniversary Blu-ray edition of Pink Flamingos. It’s the first of Waters’ so-called ‘Trash Trilogy’, which also included Female Trouble (1974) and Desperate Living (1977). After its 1972 premiere at the third Baltimore Film Festival and a disastrous screening in a Boston gay porno theatre, where, according to Flamingos actor David Lochary, “there was more action in the bathrooms than in the theatre”, distributor New Line shelved it for a year, completely flummoxed about how to market the film. This was an understandable quandary, given the film contained nudity, bestiality, rape, fellatio, cannibalism, coprophagia, and a singing bum hole.

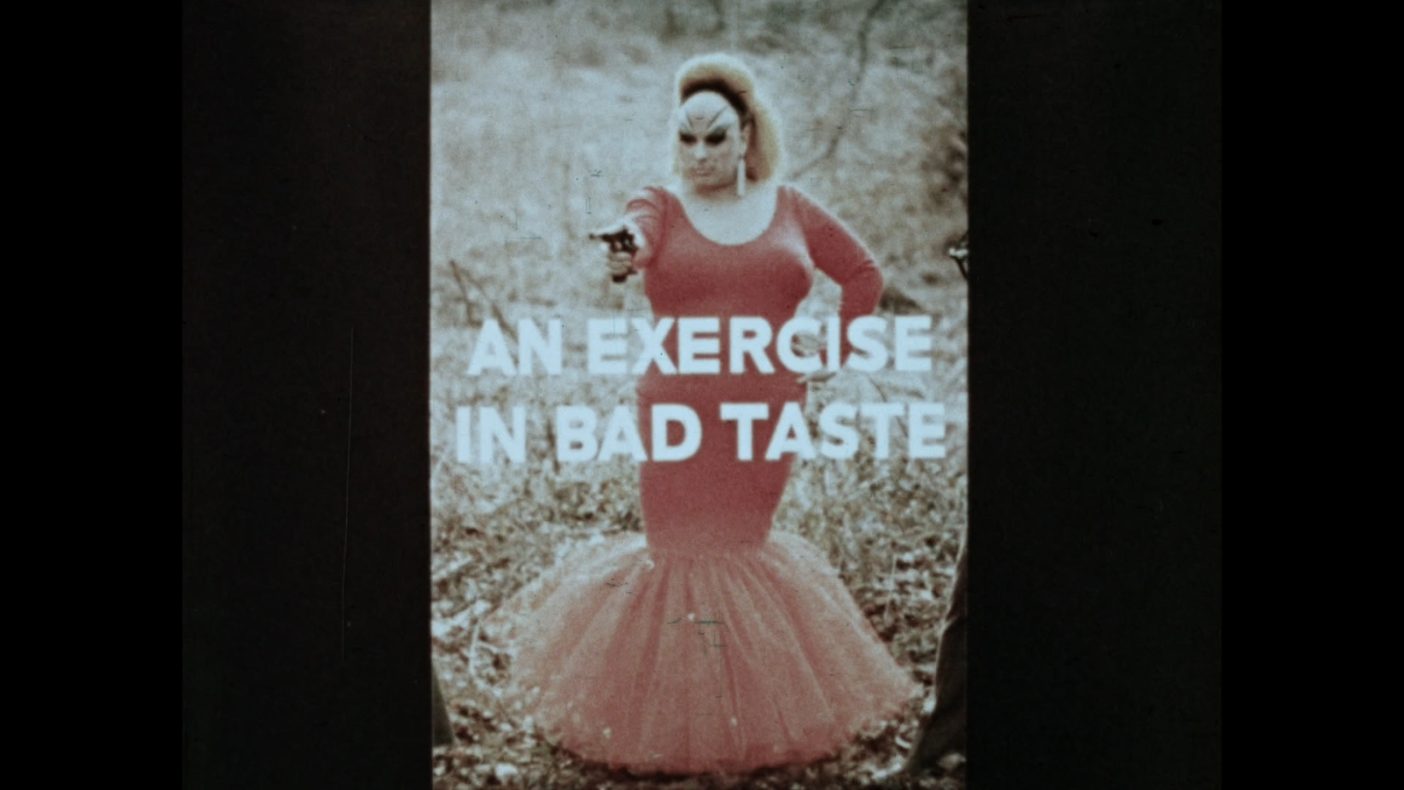

Waters instinctively understood how to market exploitation films and was somewhat furious his slice of wholesome entertainment was failing to reach the right audiences. The film’s notorious success began in February 1973, when New Line agreed Waters could open and promote it as a midnight show at Manhattan’s Elgin Theatre, with its reputation for art house programming. Pink Flamingos is the embodiment of Waters’ mantra “bad taste is what entertainment is all about. If someone vomits from watching one of my films, it’s like getting a standing ovation.” As the original promotional campaign stated, it’s “an exercise in bad taste” that offers a disturbing and often hilarious non-PC gross-out. Waters believes it’s more likely to upset today’s liberals (and he counts himself as “a bleeding-heart liberal”) than the raging conservatives of its 1970s and 1980s heyday. As Pink Flamingos turns 50 against the background of past radicalism and present culture wars, he declared “I’m against separatism — that’s my main message. I try to understand unfathomable behaviour and talk about people we don’t agree with.”

It’s described as an ‘underground’ film and, as Waters points out in the archive 1997 commentary on this disc, it could be constituted as a Weather ‘Underground’ film, given his obsession with that radical left-wing militant group. Recently added to the US Library of Congress National Film Registry as both “culturally, historically or aesthetically” important and a “landmark in queer cinema”, Waters is shocked Flamingos has been given the respect he never wanted. He never won any of the obscenity cases brought against it, and it was either banned or subject to censorship internationally. Criterion’s UK Blu-ray release presents the uncut film for the first time, after many entanglements with the British Board of Film Classification (BBFC). Back in 1973, its UK distributor was reconciled to either releasing a significantly cut version or an outright ban. Rare UK screenings in the 1970s and 1980s were, according to the BBFC, seen at members-only clubs, notably at the legendary Scala rep cinema. An uncut, uncertificated VHS was released in the early 1980s because, at the time, video was in a “legislative vacuum” until it was subject to 1984’s Video Recordings Act introduced after the ‘video nasties’ debacle.

Flamingos didn’t appear on the UK’s ‘video nasties’ list. However, when it was resubmitted for video certification in 1989, the BBFC considered either outright rejection, “in part because cutting the most offensive moments would remove the entire point of the film”, or an offer of cuts to the distributor. A cut version, removing just over three minutes of material —from the ‘chicken sex’ sequence, scenes featuring artificial insemination, fellatio, the singing bum hole, and Divine eating dog shit—made on the grounds of “sexual violence, degradation, animal cruelty, and obscenity”, was released as an 18-certificate in 1990. Did the US Library of Congress National Film Registry watch the same film?

The 25th anniversary UK theatrical release of 1997, also given an 18, still suffered over two minutes of cuts and many remained in place after it was resubmitted in 1999. For a proposed DVD release in 2008, it was granted an 18, finally without cuts, after the BBFC considered its new guidelines, the amendments to the R18 certificate to allow (and justify contextually) the depiction of real sex, and the context of freedom of expression enshrined in the 1998 Human Rights Act, that incorporated the European Convention on Human Rights into UK law (a context that could be erased if the current UK government carries out its threat to strike the Act). However, its distributor withdrew the film before the 18-certificate was granted in 2008 and until now, only the cut version was available in the UK.

I documented Waters’ creative development and childhood inspirations in reviewing Multiple Maniacs (1970). Similarly, the portrayal of villainy in Flamingos emerges from his early obsessions with The Wizard of Oz (1939), the wicked stepmother from Disney’s Cinderella (1950), The Howdy Doody Show (1947–1960), a children’s puppet and variety TV show hosted by Buffalo Bob Smith and featuring the scene-stealing Clarabell the Clown, and his violent fantasies inspired by roller coaster rides, car accidents and hurricanes. His own William Castle-inspired horror houses and puppet shows and the birthday gift of an 8mm camera then sparked off a career in filmmaking with the help of his repertory of close-knit friends.

Several key inspirations for Flamingos came from his and David Lochary’s drive to California in 1970, not only for the premier of Maniacs but also, having referenced the Manson murders in the film, an opportunity for Waters to witness for himself the theatrics of the Charles Manson trial. On the drive, he became fascinated by the numerous trailer parks scattered along the highway and imagined the terrible lives eked out in such circumstances. A mobile home eventually became the Flamingos horror house abode of Babs Johnson (Divine), a notorious criminal given the accolade of ‘the filthiest person alive’ by a local tabloid, and her very strange family, including delinquent hillbilly son Crackers (Danny Mills), voyeuristic travelling companion Cotton (Mary Vivian Pearce), and her egg-obsessed, mentally ill mother Edie (Edith Massey), who lives in a playpen (a nod to Waters’ obsession with 1956’s Baby Doll). However, criminal rivals Connie and Raymond Marble (Mink Stole, David Lochary), who run a black-market baby ring selling children to lesbians, a chain of porn shops and heroin dealers, set out to claim the title for themselves. The battle to be named ‘the filthiest person alive’ culminates with the film’s infamous final scene.

Waters had casually discussed this taboo-busting scene with his muse Divine (the alter-ego of friend Harris Glenn Milstead) when, in May 1971, they completed a San Francisco engagement of his film Mondo Trasho (1969) at North Beach’s legendary Palace Theatre. It was also one of the last appearances of genderfuck drag troupe The Cockettes. Originally entertaining filmgoers between screenings at the Palace, their shows gradually became more important than the films. Divine, thrilled to be invited by The Cockettes to participate, “pelted the audience with dead mackerel, struck glamour poses, tore telephone books in half, and threw star fits.” In the aftermath, Divine started teasing journalists about Waters’ next film, confirming that “in my next picture, I plan to eat dog shit.”

Divine’s consumption of said canine turd was one of the first scenes included in the script for Flamingos, which Waters was about to make that autumn on a budget of $12,000 loaned from his dad. It unofficially began five months of weekend shooting with the purchase of a burnt-out mobile home for $100. After relocating it, with some difficulty, to the inaccessible grounds of his friend Bob Adams’ Baltimore commune and farm, production designer Vincent Peranio rebuilt and refurbished it with his inimitable bad taste aesthetic, complete with plastic flamingos in the drive. Connie and Raymond Marble’s place was the house that Waters shared with co-star Mink Stole in Baltimore during the making of the film. Given she “had over-theatrical decorating tastes similar to mine”, Waters thought it entirely appropriate. The house became the hangout for the Dreamlanders, the regular gang of “gay, hippie pimps” that worked with Waters both in front of and behind the camera. Divine, Lochary, Stole, Pearce, Massey, Peranio and Adams were a mix of Waters’ childhood friends and a delinquent, alternative crowd from Baltimore’s gay scene.

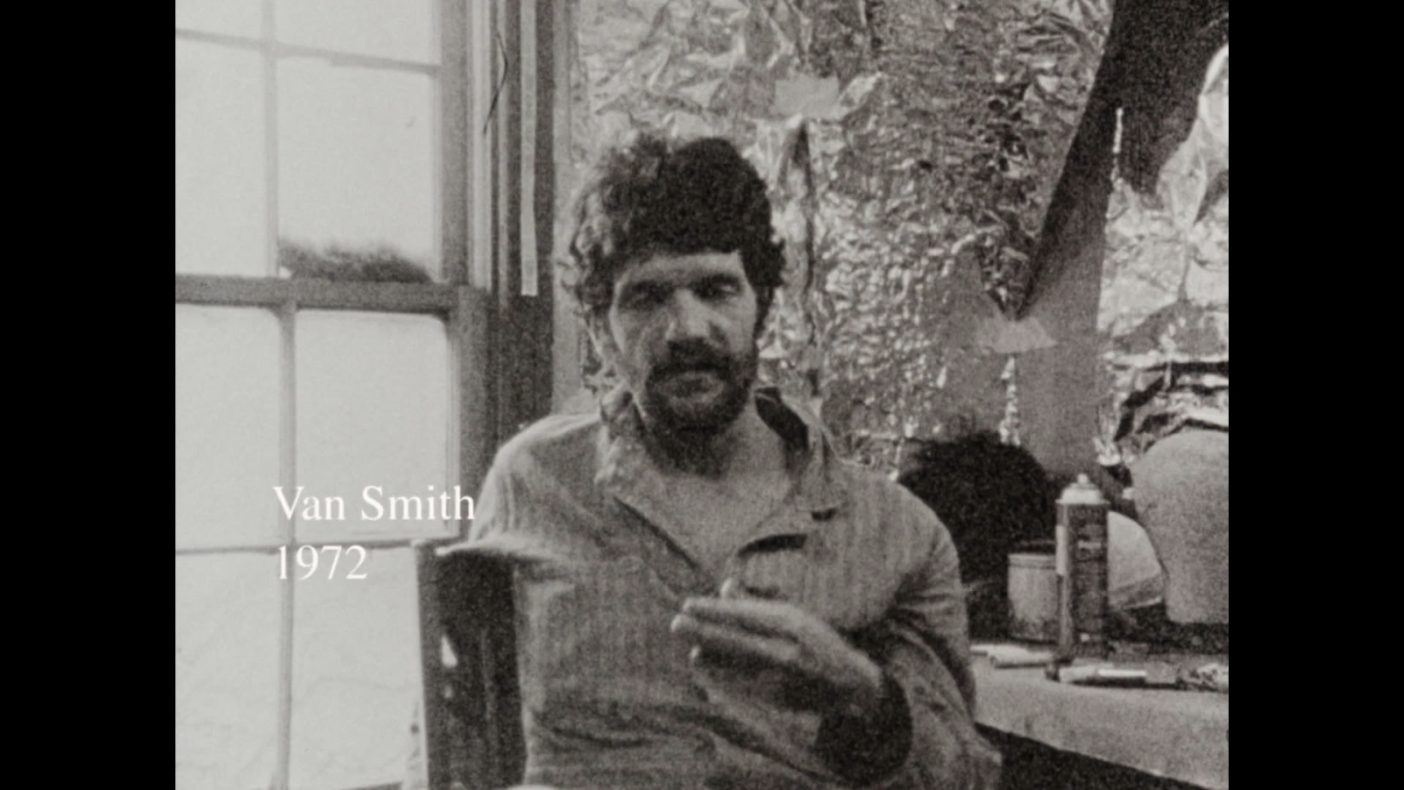

Costumes and make-up were by Van Smith, who would scour Baltimore’s second-hand shops and Salvation Army dumpsters to clothe Waters’ characters. It was a DIY aesthetic, long before Punk went mainstream, that extended to Lochary and Stole’s use of red ink and blue marker pens to dye their hair. Smith’s make-up for Divine was refined from an earlier, original look that shaved her hair back to the crown to provide a much bigger area for make-up, including “acres of eye shadow topped by McDonald’s-arch eyebrows; lashes so long they preceded the wearer; and a huge scarlet mouth.” He also had Divine’s costumes run-up “by a Baltimore woman who made outfits for strippers.” Skin-tight attire, including the signature red fishtail dress in the film, emphasised Divine’s grandiose appearance as Babs, “a cross between Jayne Mansfield and Clarabell the Clown.” When Babs parades through the streets of Baltimore, Waters doubles down on the homage by using the song “The Girl Can’t Help It”, from Mansfield’s 1956 film of the same name, on the soundtrack.

The shoot at the trailer’s Phoenix location included long days in freezing temperatures using a 300-foot extension power cord running from the commune’s farmhouse. Its basement was also used for the Marbles’ ‘dungeon’ (shades of 1991’s The Silence of the Lambs), where their servant Channing (Channing Wilroy) impregnates women kidnapped by the Marbles. Waters’ original cameraman, ‘hired’ along with the camera and sound equipment, was freaked out by the production. Technical problems, with the camera freezing, jamming and wasting film, irritated Waters because filming fell behind schedule, but this was compounded by his cameraman’s increasing inability to deal with the off-camera ‘friendly’ antics of Divine and Edith Massey (she kept the freezing cast going with a ready supply of speed), the filming of Babs receiving a dog turd in the mail, and the sex scene between Danny Mills, Cookie Mueller and freshly killed chickens. Waters fired him and, apparently, “he couldn’t have been happier.” Both cast and poultry were pushed to extremes, admittedly, but Waters reasoned that the chickens, cooked and eaten by the cast after the filming was completed, were fortunate because they “also got famous in a movie to boot.”

Mueller, having tolerated headless chickens clawing at her, also refused to take part in another scene, later dropped from the film, after she was advised not to smash a working TV set. There were concerns it would explode during Crackers and Cotton’s murderous revenge for Cookie’s betrayal of Babs to the Marbles. For one scene, Waters also intended to set Mink Stole’s hair on fire, offering to stand by with a bucket of water to douse the flames and a wig he’d bought for her to wear in the aftermath. She also drew the line. The night before filming the sequence where the Marbles send a turd in the mail to Babs, Waters casually asked Divine, “would you shit in a box and gift wrap it?” The fact that he obliged (look at the reactions when Crackers and Cotton open the box) demonstrates Divine was a star prepared to do anything as Babs, including performing fellatio on Danny Mills, as her son Crackers, and the dog shit-eating finale.

Waters later regretted the fellatio scene between Crackers and Babs. Although he claimed that friends and actors Mills and Divine didn’t feel too awkward and uncomfortable at the time, its parody of the porno chic of ’70s cinema, exemplified by Deep Throat (1972), became less and less relevant to audiences. Yet, he wouldn’t cut it now as, ironically, it would incite questions about censorship and, in part, it immortalises in celluloid what Hanjo Berressem called “a complete lexicon of abjects/abjection” in the presentation of bodily matter and fluid, citing the film’s gallery of blood, shit, saliva and semen as representational of the ‘filth’ that Waters’ outsider characters embody and the ‘assholism’ that Babs finds the Marbles guilty of in the kangaroo court scene after they burn down the trailer.

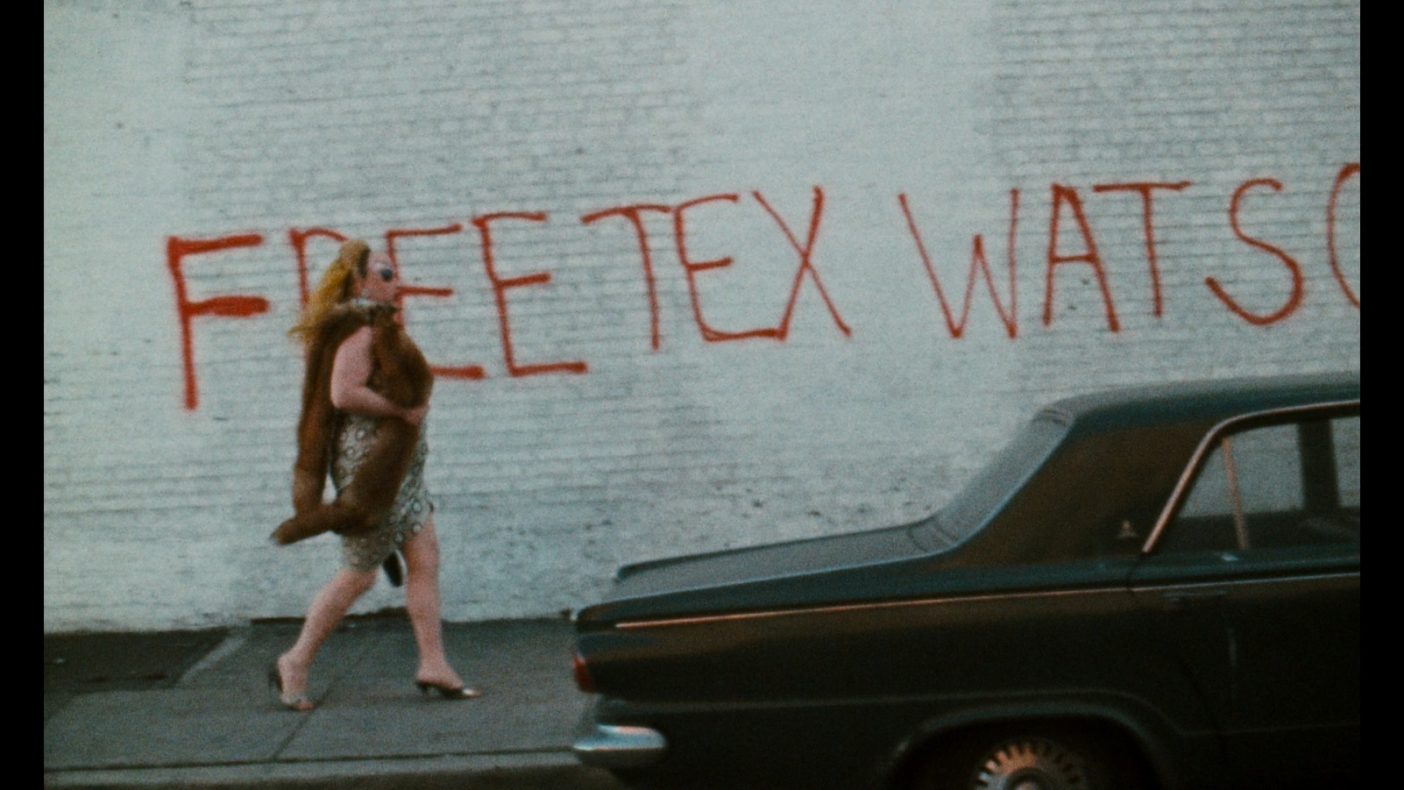

Happy to drop provocative politically incorrect statements into most interviews, Waters’ fascination with radical politics, celebrity and criminality continues to cause outrage on both the left and right of the political spectrum. As a self-confessed “terrorism voyeur”, Flamingos was his own “terrorism against hippies” and was made “as if we were all committing a comedy crime”. His preoccupations with the criminal trials of the Manson family, between mid-1970 and ’71, were reflected in the film’s dedication to ‘Sadie, Katie and Les, February 1972’. These were the aliases of three female members of the ‘family’ — Susan Atkins, Patricia Krenwinkle and Leslie Van Houten — who took part in the Tate/LaBianca murders in August 1969, under the indoctrination of Manson and Charles ‘Tex’ Watson. Divine is also seen sashaying past a wall declaring, in graffiti, ‘Free Tex Watson’, which repeats a motif, in Maniacs and, later, Female Trouble, of Divine taking to the streets, with a camera following her from a car, to declare herself to the world as a ‘filthy’ outsider. Little wonder that people were appalled by the graffiti’s appearance then and that the use of these references, as a form of ‘comedy terrorism’, still generates outraged commentary.

Flamingos’ orgy of destruction, including the numerous home invasions by rival claimants to the ‘the filthiest person alive’ accolade, is a skewed representation of the Manson family attacks. The film’s class and cultural inequalities are filtered through Waters’ view of Manson as “the great American bogeyman” and the threat his LSD-crazed hippy cult represented the middle-class straight white people. Waters’ advocacy for mass murderer Leslie Van Houten’s parole, whose fifth recommendation was rejected by the California Supreme Court as recently as February 2022, continues to polarise people. He has since regretted his treatment of the Manson murders in “a jokey, smart-ass way… without the slightest feeling for the victims’ families or the lives of the brainwashed Manson killer kids who were also victims in this sad and terrible case.”

His uncomfortable observation that “that the Manson family looked just like all my friends at the time”, does problematise an anarchic, divisive comedy that was destined for “an audience of people who were angry and had a sense of humour about themselves and didn’t fit in their own minority.” Babs spouts a ridiculous manifesto of sorts at the end of the film when she is being interviewed by journalists: “Kill everyone now! Condone first-degree murder! Advocate cannibalism! Eat shit! Filth is my politics! Filth is my life!” The scene conflates the Manson family with many other radicals who came to trial in the 1970s, including another Waters inspiration, the Weather Underground group that emerged from the student protests of the late-1960s and organised riots, bombings, arson attacks, and jailbreaks.

The class and culture warfare in Flamingos is startlingly current. The Marbles believe, in their surreal ‘keeping up with the Joneses’ campaign, that they have the cultural whip-hand over the trailer-dwelling Babs Johnson and her family. Babs’ authority wins out as the lesser of two evils. The war between families and against authority is a recurring theme in many of Waters’ films, as is an anger that’s the antithesis to suburban normality. The gory homage to Night of the Living Dead (1968), where Babs and her birthday guests kill and eat the cops sent by the Marbles, symbolises this “hatred of authority and using humour as a weapon.”

It extends to the film’s audience who are invited to vicariously experience a visceral and transgressive vindication of the glamour of criminal notoriety and the toxicity of celebrity. While the film continues to bubble and seethe with subversion and outrage, it’s worth appreciating Divine’s outstanding work in a cast of true eccentrics and misfits. It combines a natural acting talent and gift for comedy to create, in Babs, a complete character and confirms Divine’s own ‘stardom’. Despite its awkward aesthetics —single camera setups, long takes, and reams of dialogue punctuated by shock tactics —there’s still a great sense in Flamingos that Waters, always one to touch a nerve to this day, was testing the “limits of suffering”, seeing how far his actors and his audience would go for art and entertainment. The ‘Pink Phlegm-ingo Barf Bag’, originally handed out at some screenings, has not yet been made redundant for this ridiculously filthy, not in the least bit respectable, film that continues to revolt and amuse in equal measure.

USA | 1972 | 92 MINUTES • 107 MINUTES (1997 RE-RELEASE) | COLOUR | ENGLISH

writer & director: John Waters.

starring: Divine, David Lochary, Mink Stole, Mary Vivian Pearce, Danny Mills & Edith Massey.