Giallo Essentials (1972-74)

Only a few years ago, the term giallo wasn’t common parlance, even amongst cult movie enthusiasts. Recently, that’s changed, and the genre’s enjoyed a renaissance along with critical reappraisal. Now younger filmmakers are picking and mixing the tropes and we’re starting to see an influence in a new batch of post-modern neo-gialli thrillers, most recently exemplified by Michele Civetta’s Agony (2020), Prano Bailey-Bond’s Censor (2021) and Edgar Wright’s Last Night in Soho (2021). So, basic background knowledge is now essential for any movie buff.

The genre has become so strongly associated with one particular set of auteurs—Mario Bava, Dario Argento, Sergio Martino—that some notable contributions from others during its formative years have been overlooked. This new Giallo Essentials box set from Arrow Video partly redresses this by showcasing a trio of neglected examples from directors who only dabbled in the genre. The two earlier films here—Silvio Amadio’s Smile Before Death (1972), and Francesco Mazzei’s The Weapon, the Hour, the Motive (1972)—were made when the giallo formula was still fresh and are, as one might expect, more interesting than the third offering, Giuseppe Bennati’s The Killer Reserved Nine Seats (1974), released just two years later when the popularity of the genre was already beginning to wane…

A teenage schoolgirl returns home after the death of her mother to inherit the estate, but her stepfather and his lover have other plans for her.

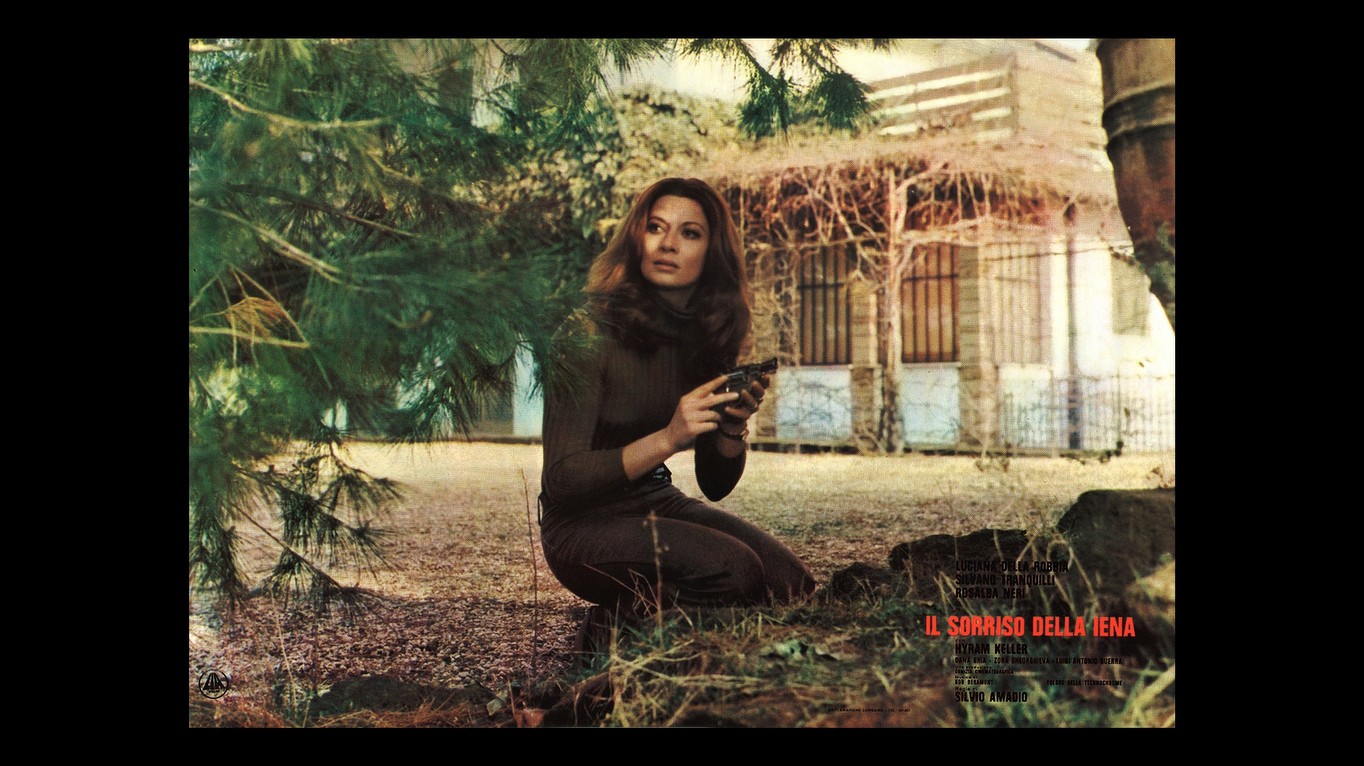

Smile Before Death stands out as the strongest among these early and lesser-known examples of this resurgent genre. It’s also the most welcome as it’s been rarely seen outside Italy and certainly never before in its pristinely restored, full-screen glory. It’s pretty much a definitive example and would serve as a good initiation for those new to giallo.

A scream leaps out from blackness before a woman, in a yellow negligee, with almost fluorescent blood streaming from her slashed throat, staggers and falls to the floor of a starkly modern bathroom. We then cut to close-ups of the police crime scene photographs and hear the coroner summarising that the victim, Dorothy Emerson (Zora Gheorgieva), had high levels of alcohol in her blood and the shard of glass found in her hand bore only her fingerprints and, what’s more, the bathroom was locked from the inside. The conclusion is a suicide, but observant viewers may notice subtle differences between the scene we just witnessed and how it looks in those forensic photos. Poor continuity or deliberate misdirection?

After that abrupt, slap-round-the-chops opening, we then have the title sequence of establishing shots in and around Rome, accompanied by the incongruously upbeat and potentially annoying theme consisting of the word ‘achoo’ vocalised with playful sexuality by Edda Dell-Orso. She’s now best remembered for her expressive vocal contributions to many scores by Ennio Morricone, including the sublime Ecstasy of Gold from the climax of The Good, The Bad, and the Ugly (1966). Here, the composer is Roberto Pregadio, who serves a quirky array of moods throughout, from euro-pop more suited to a romantic comedy to manic organs and off-key pianos. It’s a strong, distinctive soundtrack that some may find obtrusive, though most will be humming that title theme earworm days later!

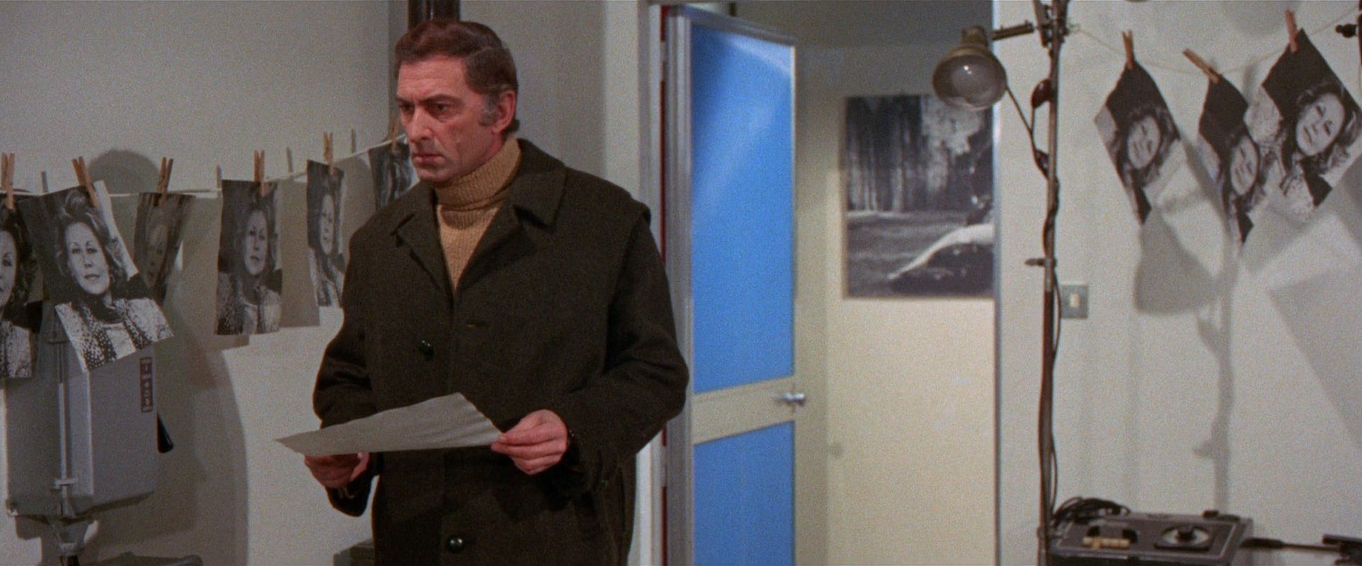

Dorothy’s estranged daughter, Nancy (Jenny Tamburi), who’s been away at boarding school in England, arrives at the well-appointed Emerson abode and seems surprised to be greeted there by a stranger, Gianna (Rosalba Neri), who explains she’d been a good friend of her late mother and had been using the basement as her studio and darkroom. Neither of them seems too upset about the death of Dorothy as they strike up a friendship, with Nancy becoming Gianna’s model and muse.

The central concept of photographing people who are roleplaying a character or, conversely, attempting to capture someone’s true personality on film is used as a clever narrative device. Photographing a photographer at work draws the viewer’s attention to what’s been selected for their eyes and how it’s shown to them. Every image is mediated in some way, and we’re trained to think about the choice of angle and framing. What is just outside the picture we see? What happened just before the edit or the moment following the cut? What is obscured by something in the way? Are we interpreting what we do see correctly? A good giallo will nearly always employ such methods.

It was the first leading role for Jenny Tamburi and for such a young actress, aged just 19, there’s plenty to get her teeth into. Her portrayal of a precocious teenager is nuanced and layered. Nancy’s not shy about flaunting her nudity to manipulate and seduce both her stepfather, Marco (Silvano Tranquilli) and Gianna, who had been his illicit lover—perhaps also Dorothy’s. Yes, seventies libertine sensibilities abound and may not sit well with a modern, politically correct audience. Then again, gialli don’t usually attract that kind of conservative viewer.

The abundant female nudity is presented as if to satisfy the male gaze, however, even this perception is subverted to some extent as we come to realise that Nancy’s seductive poses are also aimed at seducing her female photographer. Admittedly the nudity is there for audience titillation but dismissing it as ‘gratuitous’ would be a disservice. It’s tastefully done and does play an important narrative role.

All the cast conduct themselves with confidence and although the acting style couldn’t be described as naturalistic, it’s clear and serves the story admirably. Silvano Tranquilli also plays a multi-faceted character who is not quite as he appears to be. He’d already appeared in three formative gialli, The Black Belly of the Tarantula (1971), The Double (1971), and Duccio Tessari’s The Bloodstained Butterfly (1971), and went straight onto filming a fifth, So Sweet, So Dead (1972). Fan favourite Rosalba Neri was a veteran of pulp cinema with around 80 previous appearances and fresh from the set of Amuck (1972), the only other giallo from the same director…

Interestingly, Hiram Keller, who only appears briefly, got top-billing on the promo materials—although his name was misspelt. He’d starred in the first stage production of Hair on Broadway and this launched his screen career in the starring role of Fellini Satyricon (1969) instantly making him a hot young actor in Italy. His career didn’t take off as expected though he does appear in another entertaining giallo set in Scotland, Antonio Margheriti’s Seven Deaths in the Cat’s Eyes (1974). Dana Ghia also deserves an honourable mention here as the ambiguous Magda, the housekeeper who makes a key incriminating discovery and then some bad choices about what to do with the knowledge. She was fresh off the set of The Bloodstained Butterfly, where she’d just worked with Silvano Tranquilli.

Writer-director Silvio Amadio is the most experienced of the three showcased in this box set, so it may come as no surprise that his offering is, by far, the most accomplished. His debut had been Lupi nell’Abisso / Wolves of the Deep (1959)—a claustrophobic maritime war drama set onboard a stricken submarine. Then, he’d turned his hand to the usual mixed bag of peplum, spaghetti westerns, crime dramas, and a few sex comedies. He’d skirted the giallo with Assassination in Rome (1965), a thriller with Hitchcockian intrigue surrounding a kidnapping of an American tourist that tried to capitalise on the success of Mario Bava’s similarly plotted The Girl Who Knew Too Much (1963)—often cited as the progenitor of the genre.

The slick cinematography of Silvano Ippoliti is superb. His compositions use the full potential of a widescreen frame, and he shows off the stylish 1970s décor to great effect. He was already just over a decade into a prolific, 35-year career and had turned his hand to many genres, including some striking work on two Sergio Corbucci spaghetti westerns, Navajo Joe (1966) and The Great Silence (1968) and, just the year before, Ricardo Freda’s giallo set in Ireland, The Iguana with the Tongue of Fire (1971).

Smile Before Death was released a couple of months ahead of Sergio Martino’s well-regarded Your Vice Is a Locked Room and Only I Have the Key (1972) and shares several remarkably similar plot points. Inevitably, the two films have drawn comparisons but they’re different enough in tone to make it difficult to judge which is superior. The former is a sexy playful giallo that doesn’t demand to be taken too seriously. It certainly makes for easier viewing overall, though the murder scenes are suitably harsh, and it’s the clear winner in the seventies chic stakes with sets dressed like an interior design expo, whereas the latter riffs on its more gothic Edgar Allan Poe source material in crumbling mansion surroundings and revels in sadistic and resentful interactions between characters.

Smile Before Death may not have a high enough body count for some giallo aficionados but there’s still a cleverly contrived mystery at the core of this well-executed thriller. Although anyone paying attention will have worked it all out by the end of the second act, the interpersonal intrigue means we’re hooked by then and still want to see how the machinations will play out. Will they get away with it? Are there any reasonably redeemable characters? Who will survive to the end credits? It may not be the greatest giallo, but it’s certainly a stylish and very satisfying one that does everything a fan wants from the genre.

ITALY | 1972 | 88 MINUTES | COLOUR | ITALIAN

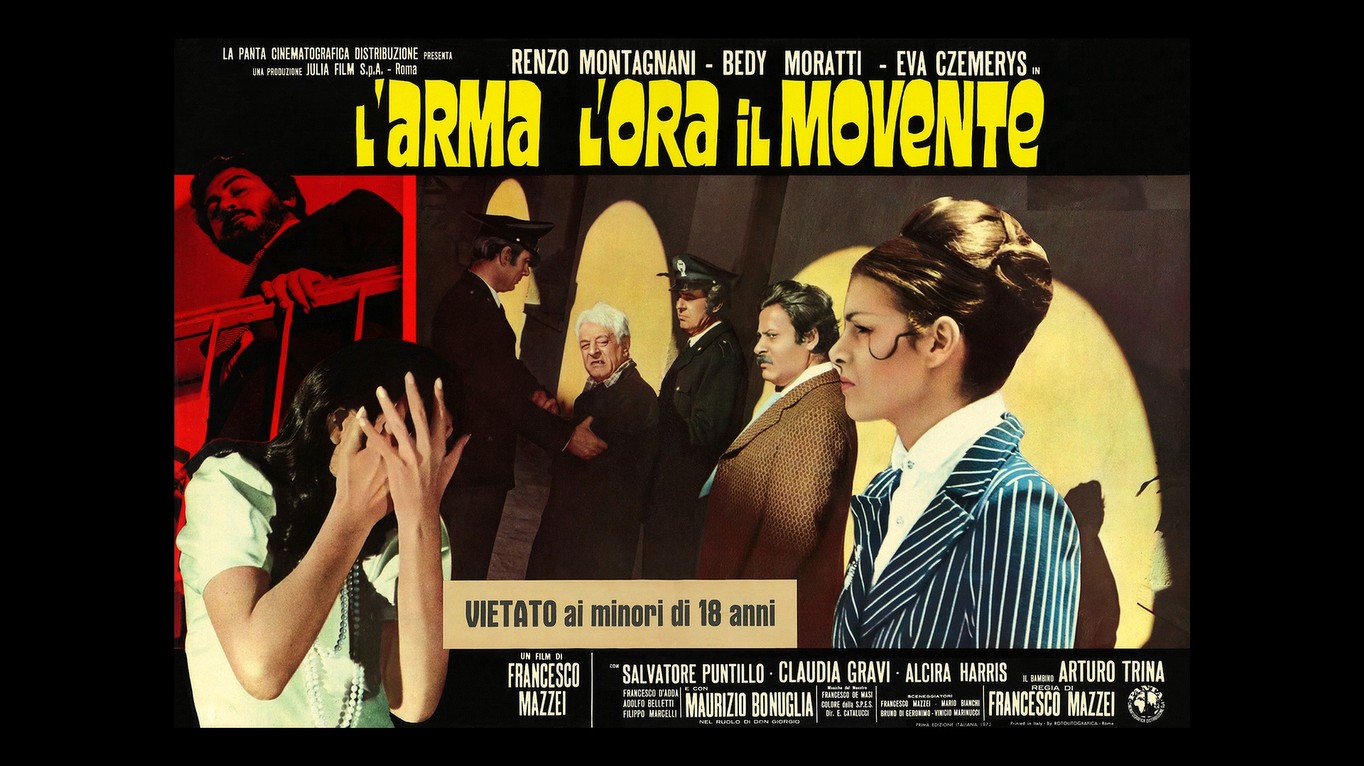

Horny priests and perverted nuns lead to murder at the altar in this off-beat police procedural thriller.

The Weapon, the Hour, the Motive is an interesting movie that never gets boring but relies too much on a certain degree of suspension of disbelief. The audience is expected to simply accept that Mediterranean temperaments are all volatile and libido driven. It’s unpredictable and almost, but not quite, clever. There are original and rather inspired plot components, though it shares some thematic parallels with Lucio Fulci’s Don’t Torture a Duckling (1972), as both films feature a clergyman lacking in self-restraint, though here he’s the victim whose death triggers a convoluted whodunnit. It also borrows a lot from Edgar Allan Poe’s story The Black Cat. (But it seems a giallo that doesn’t is a rare thing!)

Director Francesco Mazzei is marginally better known as a producer of a few exploitation ‘documentaries’ and sexploitation ‘comedies’ and this is his sole stint in the director’s chair. Maybe he was trying to cram all his ideas into one vehicle? He certainly manages to maintain visual interest throughout. He appears to be using a rather heavy subtext concerning the conflicts of church and state, law and liberty, to justify eroticism and a gratuitously long sequence of topless nuns engaged in gasping self-flagellation that fits into the trashy Italian subgenre of nunsploitation.

Much is made of the contrast between handsome Father Don Giorgio (Maurizio Bonuglia) and the old and toothless Sacristan (Adolfo Belletti) as the only two adult males in a convent. It’s quickly established that the Sacristan has a dark past and Don Girogio is providing more than spiritual comfort to some of his more glamorous parishioners whilst wrestling with this weakness within himself. There is a famous artwork called ‘The Vision after the Sermon’—painted by Paul Gauguin in 1888 after spending time with Vincent van Gogh—that depicts a bunch of wimpled nuns seeing a vision evoked by the impassioned sermon given by a priest (the only male in the composition). There’s a seemingly knowing reference to the painting in the scene where the dead priest is discovered by the sisters.

The main plot hook, and source of much of the suspense, is that the audience knows that Ferruccio, the altar boy (Arturo Trina) witnessed the murder. His secret hiding place was in the chapel’s attic space where he’d made, or found, a spy hole through the ceiling. Presumably positioned to provide a bird’s eye view of nude nuns whipping themselves—just the sort of thing to interest and confuse a young lad. Problem is, that in his shock, one of his prize marbles dropped through the peephole and alerted the killer to the presence of a voyeur. Who has the marble, and which marble was retrieved from the chapel, becomes significant.

When Inspector Boito (Renzo Montagnani) turns up at the crime scene, he’s frustrated that Sister Tarquinia (Claudia Gravy), a somewhat glamorous nun, has already moved the body for ‘preparation’. Lacking forensic evidence, he decides to build a picture of the victim as he’d been in life and so questions those close to the promiscuous clergyman. It’s not long before he embarks on an affair with Orchidea (Bedy Moratti) a married woman who had also been one of Don Giorgio’s lovers. She’s also the carer for the orphan altar boy and administers his regular injections as treatment for a mystery ailment.

So many red herrings! One gets the impression that the plentiful, unexplored subplots are perhaps more interesting than the thread we’re following. I mean, what about that goth crypt with dead monks and nuns set up in some sort of satanic tableaux around a snooker table? Not sure why no one mentioned that to the police. I guess it was so we’d assume it was the handiwork of the glamorous nun. Which it must’ve been, or perhaps the boy’s…

There are plenty of interesting ideas lost in a morass of admirable misdirection that keeps things interesting but ultimately feels like a cheat. Some great imagery can also be enjoyed along the way, but none of that really comes together or contributes to the central narrative. Perhaps the whole thing was just one big excuse for the naked nuns and orgies of self-flagellation. There’s an implication that the murderer may be the product of the societal-scale repression of sexual urges as the 1970s liberal lifestyles erode the traditional dominance of the church. But even that fails to come to the fore, well not any more than a mention of Haiti and the implication of voodoo or maybe some good old-fashioned black magic.

ITALY | 1972 | 105 MINUTES | COLOUR | ITALIAN

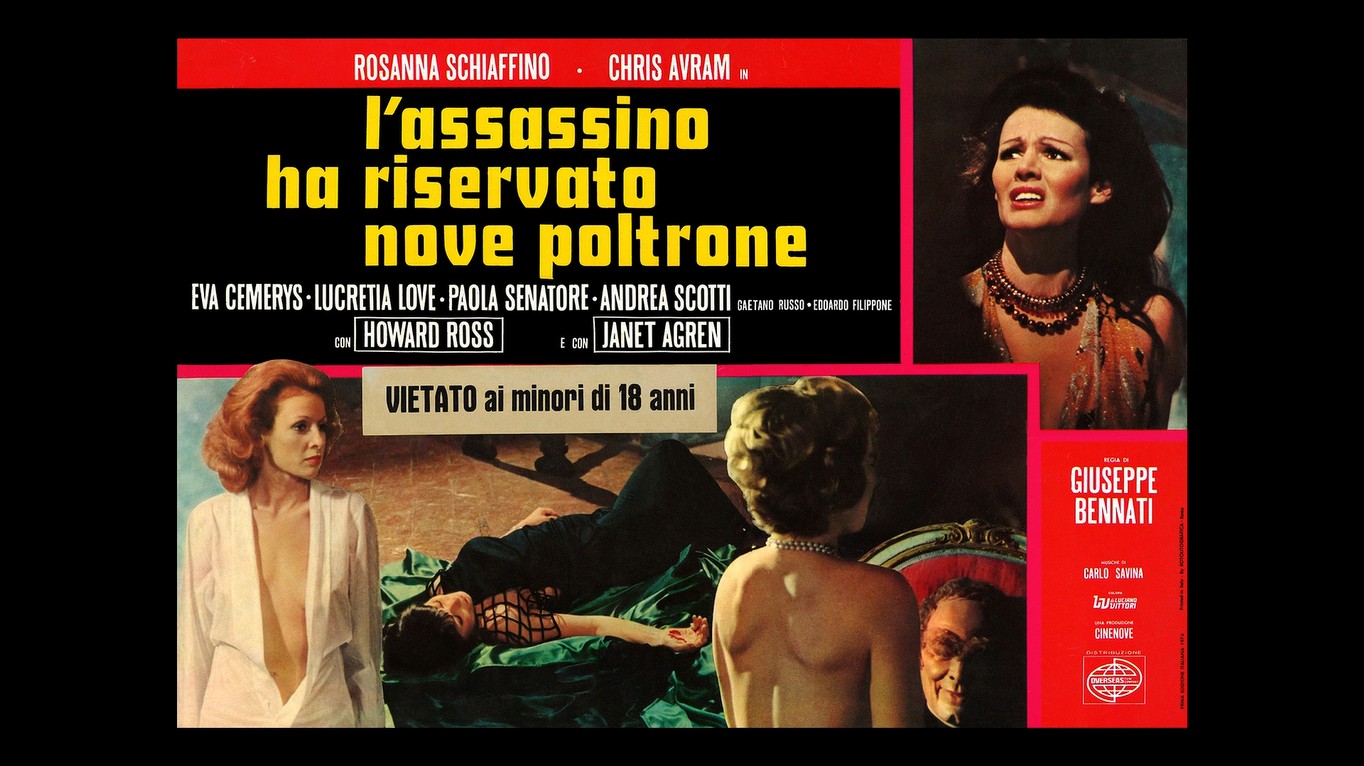

A group of rich degenerates gather to spend the night in a spooky theatre and masked killer takes advantage of the situation to murder them one by one.

In a career spanning three decades, writer-director Giuseppe Bennati only made nine unremarkable films, an assortment of comedies and dramas. That’s meagre for a jobbing director during the golden age of Italian cinema. The Killer Reserved Nine Seats was his only giallo and a lack of experience in the genre comes through with clumsy pacing and a confused, if not corny, denouement.

In the come-down after a society party, a group of wealthy acquaintances—they can’t really be called friends—decide to spend the night together in an old, abandoned theatre belonging to their host, Patrick Davenant (Chris Avram). The lavish theatre was once the palatial home of his ancestors and is said to be haunted. He recounts a legend that once every century, on a particular date, the heirs to the noble family’s fortune gathered in the palace for an orgy of incest and murder, from which only one ever escapes alive to continue their cursed line.

To add to the spookiness all the exits are closed, and the sturdy old doors are locked, barred and bolted. The keys are left in the foyer for anyone who wants to chicken out. The whole scenario is unashamedly based on Agatha Christie’s best-selling mystery thriller, And Then There Were None—first published in 1939 under the unacceptable title of Ten Little Niggers—in which the guests at an isolated mansion are knocked off one by one. Each murder is prescribed by the 1860s children’s rhyme of the same title. The Killer Reserved Nine Seats was a deliberate reference to this and in place of the rhyme, an old parchment portrays nine horrific ways to die. It’s supposed to be 500 years old, placing it in the Renaissance period, though its style of illustration is anachronistic and clearly contemporary.

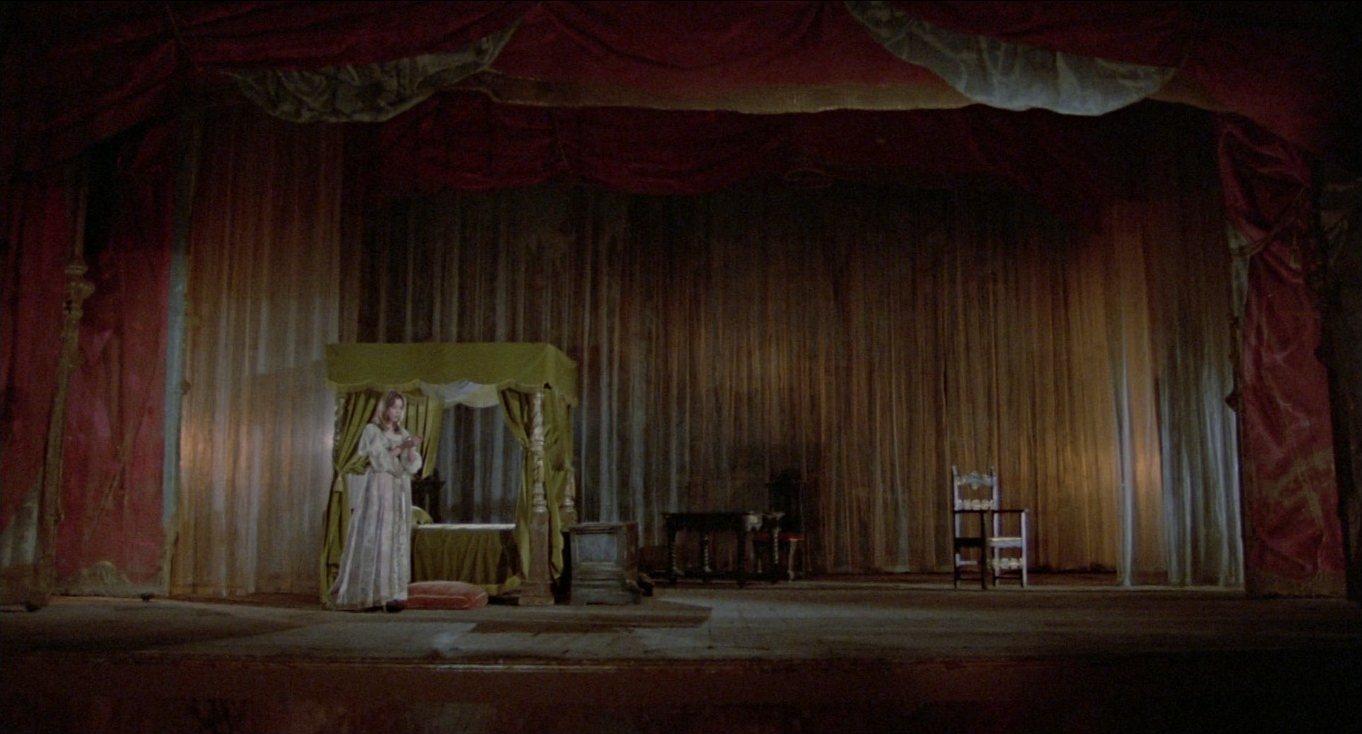

We’re 20-minutes in when we see the black-gloved hands of the killer use a knife to sever the cord suspending a counterweight over the stage which falls, narrowly missing Patrick. One good thing about this movie is its moody use of a theatre setting that owes much to Paul Leni’s final film, The Last Warning (1928) a classic mystery thriller also set in a supposedly haunted theatre.

The first successful killing occurs as Kim (Janet Agren) is demonstrating her acting prowess by delivering Juliet’s death monologue from Romeo and Juliet when she stabs herself after delivering the line, “O happy dagger, this is thy sheath, there rust, and let me die.” Her death is a little too convincing to those watching. Russell (Howard Ross) rushes onto the stage to discover that she’d been stabbed in the back with a real dagger. In the ensuing panic, it’s difficult to work out if anyone was missing from the auditorium at the moment of the murder…

Of course, when they try to call the police, the telephone line has been cut and yes, you guessed it, the set of keys has been removed from the foyer. Add to this that most of the party is worse for wear after a night of cocktails and recreational substances and perhaps we can go along with the irrational behaviour that follows, enabling the unconvincing scenario peppered with set-pieces that would be rather silly if they weren’t so nasty.

All the players are suspects, at least until they wind up dead, because everyone seems to have had an affair with everyone else, or they know some blackmailable secret about one another. There’s lots of barbed dialogue and gaslighting going on. The only sympathetic character turns out to be ex-prostitute Vivian (Rosanna Schiaffino). The cast doesn’t seem to understand their roles and, for the most part, are simply called upon to deliver plenty of cryptic mumbo-jumbo which they do rather robotically. Perhaps they are conveying the ennui of their bourgeois lives? Or, maybe, that should be la noia, in Italian.

The murder scenes are varied with a few successfully building the suspense until a well-choreographed crescendo is reached. Others seem a bit rushed and throw-away as if the budget ran out. The one truly giallo-style climax is when a tableau featuring the naked corpses of Doris (Lucretia Love) and Rebecca Davenant (Eva Czemerys) is dramatically lowered onto the theatre stage.

One murder stands out for its misogynistic sado-sexual brutality that suggests a maniac with a juvenile mind. Was there a mention of a missing brother who was taken away to an asylum years ago? Oh, yes, there’s also a mystery man (Eduardo Filipone) who poses with roses to deliver dire warnings to Patrick. He may, or may not, be a ghost and may, or may not, be the caped person behind the rubber mask. Yes, at times it does get a bit Scooby-Doo!

There’s a tight plot hinted at but left terribly frayed around the edges. Although there’s only a small cast, there are still too many characters and red herrings to keep track of and, by the end, it’s hard to care too much about who survives or what the murderous motives were. Indeed, the final reveal of who the villain orchestrating the murders actually was may have been a real let-down if we weren’t just happy to get out of the theatre by then. There’s a blatant but brief hint, but it’s never really made clear enough, leaving much for the viewer to surmise.

What we’re left with is a poor imitation of an Agatha Christie ‘whodunnit’ with some particularly nasty death scenes thrown in, hoping to distract from a flimsy plot with bitchy bickering, drug-fuelled incest, gratuitous sex, and sexualised violence. When the most positive thing to be said is, that it would’ve been banned in the UK the first time around, one realises there aren’t many redeeming factors. And, although this is the only film in this set with a masked and black-gloved killer, boasting the biggest body count, it fails to tick several of the essential giallo boxes. Ultimately, one wonders if it really deserves to be included here.

ITALY | 1974 | 104 MINUTES | COLOUR | ITALIAN

directors: Silvio Amadio (Smile) • Francesco Mazzei (Weapon) • Giuseppe Bennati (Killer).

writers: Silvio Amadio & Francesco Villa (Smile) • Francesco Mazzei, Marcello Aliprandi, Mario Bianchi, Bruno Di Geronimo & Vinicio Marinucci (Weapon) • Biagio Proietti, Paolo Levi & Giuseppe Bennati (Killer).

starring: Jenny Tamburi, Silvano Tranquilli & Rosalba Neri (Smile) • Renzo Montagnani, Eva Czemerys & Bedy Moratti (Weapon) • Rosanna Schiaffino, Chris Avram & Eva Czemerys (Killer).