FEMALE TROUBLE (1974)

A spoiled schoolgirl runs away from home, gets pregnant while hitchhiking, and ends up as a fashion model for a pair of beauticians who like to photograph women committing crimes.

A spoiled schoolgirl runs away from home, gets pregnant while hitchhiking, and ends up as a fashion model for a pair of beauticians who like to photograph women committing crimes.

This month Criterion return to the work of John Waters with a feature-packed high-definition release of Female Trouble (1974). The film and its ‘trash trilogy’ companions Pink Flamingos (1972) and Desperate Living (1977) are justly celebrated as “instances of outlaw cinema ne plus ultra.” Shot on a budget of $27,000 between Autumn 1973 and Spring 1974, Female Trouble defines the essence of Waters’ aesthetic sensibility. It also makes no concessions to political correctness. More than an oft-labelled camp trash fest, it’s Waters’ wickedly funny take on outsiderdom, sexuality, gender, the criminal classes, and the power of celebrity.

In my reviews of the previous Criterion releases of Multiple Maniacs (1970) and Polyester (1981), I’ve explored the development of Waters’ work in parallel with the rise of his repertory company of actors, set and costume designers, and producers, collectively known as the Dreamlanders. After Pink Flamingos was crowned “the sickest movie ever made” and went on to play the Elgin Theatre in Greenwich Village seven nights a week for three years, Waters and his Dreamlanders rose to the daunting challenge of following it up with what many believe is Waters’ best film, Female Trouble. Originally known as Rotten Mind, Rotten Face, it was changed to Female Trouble because Waters felt critics would add ‘Rotten Movie’ to that title. As he reassembled the Dreamlanders again in Baltimore, Waters realised that a different approach was needed and, instead of trying to “top the shit-eating scene in Pink Flamingos”, he decided he “wanted the ideals rather than the action of Female Trouble to be horrifying.”

The budget was a combination of earnings from Flamingos and money borrowed from Jim McKenzie at the University of Maryland’s Cinémathèque and a wealthy friend, Jimmy Hutzler. With it, he was able to attract, courtesy of uncredited line producer Leroy Morais, the Head of Fine Art at University of Maryland Baltimore County (UMBC), a professional crew to help him and production manager Pat Moran. They included future line producer Bob Maier, editor Charles Roggero, and cinematographer Dave Insley. While Insley and Roggero were unaware of what they were about to let themselves in for, Maier knew of Waters and his entourage after they’d been pointed out to him during a trip to Provincetown in 1969.

Maier worked at the UMBC when Waters came looking for crew and equipment. Having taken the trouble to familiarise himself with Flamingos, his trepidation at actually meeting Waters turned to an endearment that sealed their social and professional friendship across five films. “You expect a monster, but he could pass for an assistant Presbyterian minister trolling for church members,” he recalled of that first face-to-face encounter. Maier was able to get Waters access to the University’s superior audio-visual equipment under Morais’ proposal that, in exchange, the film department’s more competent student interns could gain work experience on the production.

Initially, Maier worked out of an office but was urgently pressed into action as a sound recordist on Female Trouble when the previous incumbent was found shooting up in a bathroom and was banished from Waters’ set. As Maier noted of Waters’ aim for greater professionalism: “he did not want to be known as an uncivilised geek who lived in a trailer surrounded by deranged misfits.” While Insley, a teaching assistant at UMBC, worked as a camera assistant and on lighting, Waters was also joined by Masters student Roggero during the editing process and became the de facto editor of Female Trouble. Again, like Insley and Maier, Roggero became part of the Waters family. He continued as editor on several films until he sued Waters, and won, in a dispute with producers New Line over breach of contract on Hairspray (1988).

The relationship between the more professional members of Waters’ crew and his Dreamlanders entourage was a little fractious. Regular collaborator Vincent Peranio meticulously constructed and dressed the sets but found it hard to adjust to the technical step up that the film represented when his work was moved around for better lighting and angles. As Maier recalled, Waters was equally irked when his UMBC crew tried to inject the same professionalism into filming: “John’s style was to plop the camera down and never move it, and he’d argue every time we tried to get him to shoot a close-up, reaction shot, or other cutaway.” Even the catering arrangements and daily payments for the UMBC crew were contentious. The latter triggered the Dreamlanders to petition Waters, during the making of Female Trouble, about their share of the profits from his films.

Waters’ script was partly inspired by his early obsession with criminal trials, including those of Alice Crimmins, the Chicago Eight, and Charles Manson. He developed a friendship with Charles ‘Tex’ Watson, one of Manson’s infamous ‘family’ sentenced to death for his involvement in the Tate-LaBianca murders. Visiting Watson in prison, he recognised the allure of criminality in all the celebrity hangers-on and disciples in the visiting rooms. Criminality and celebrity, ‘crime as beauty’, and the effects of media saturation on ordinary people became the central tenets of Female Trouble and, although the film was dedicated to Watson, in his book Role Models Waters later questioned his decision to do so.

While Waters’ early films have, in retrospect, been accommodated within a contemporary camp, gay sensibility, Chris Holmlund rightly points out that Female Trouble is a synthesis of many other influences rooted in the countercultural aesthetic of the 1960s. The Dreamlanders were the successors to absurdist Charles Ludlam and the legacy of his Ridiculous Theatre Company, Jack Smith’s satirical take on Hollywood, Flaming Creatures (1963), and the work of experimental filmmakers Kenneth Anger and George and Mike Kuchar. Female Trouble also throws into the mix Diane Arbus photography, anarchic Dadaism, and the resistance that Waters and his Dreamlanders had to the establishment represented by schools and the Catholic church. The film also consolidates Waters’ own cinematic acknowledgement of Douglas Sirk, Herschell Gordon Lewis, Russ Meyer, and William Castle in its evocation of melodrama, horror and exploitation.

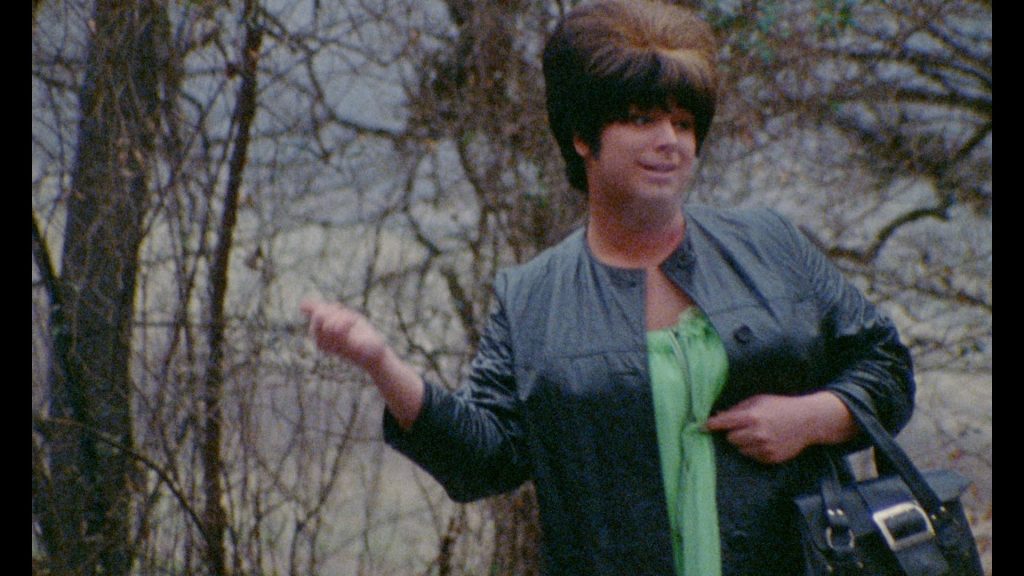

With a crew assembled, Waters began shooting on a film that eventually left critic Rex Reed wondering, “Where do these people come from? Where do they go when the sun goes down? Isn’t there a law or something?” Female Trouble was filmed over ten days and mainly at weekends, guerilla-style on the streets of Baltimore (without any permits) and at various indoor locations, including a law school, a church, a hospital medical school, the Lipstick Beauty salon, Pat Moran’s thrift shop ‘Divine Trash’, a tent store, Peranio and Waters’ homes and, the cherry on the cake, Baltimore city jail (apparently, the warden was a Flamingos fan). Maier recalled the astonishment of passers-by when the film’s star Divine (a.k.a Harris Glen Milstead) was being filmed on the street from a moving car or the alarmed neighbours of the house loaned to the production in Lutherville when Divine, as lead character Dawn Davenport, storms out of her home, berating her parents for not buying her the cha-cha heels she wanted for Christmas.

The combination of Vincent Peranio and Van Smith’s sets, costumes and makeup and the Dreamlanders’ unorthodox performance styles supported a narrative that traces the life of headline-seeking criminal Dawn Davenport (“the best vehicle for Divine”, as Waters acknowledged) from teenage brat to a non-repentant criminal executed in an electric chair. After the opening song, with lyrics by Waters and recorded by Divine in an LA recording studio, the film commences with Dawn’s high school years, heralded with the title card ‘Dawn Davenport —- Youth —- 1960′. It’s interesting to note the structure of the film at this point, the narrative progressing as each title card appears, perhaps emulating Tony Richardson’s film of Henry Fielding’s Tom Jones (1962) or Kubrick’s adaptation of Thackeray’s Barry Lyndon (1975).

While such high art influences on Female Trouble don’t include an off-screen narrator, both novels and their respective films share with Female Trouble a mock-Bildungsroman fable that explores questionable morality, social pressures and outsiderdom, and genres such as melodrama, tragedy and comedy. Certainly Waters’ film reflects some of Fielding’s bawdy, carnivalesque qualities but the triumph of a comic hero over his or her betters is taken to a nightmarish extreme.

Of greater importance, Waters is recreating his memories of Towson Junior High School, where he first encountered what he refers to as “trashy girls” and learned “about fashion and extreme teenage styles.” Dawn was based on the “worst delinquent in the school” and she’s a recognisable representation of his and the Dreamlanders’ attitudes, ever-present in his work and that reached a peak in Hairspray. Her rebellious nature is typical of his many teenage rebels that were either determined to be on the wrong side of the tracks or were very susceptible to being tempted onto them. It also sets up the template of the rebellious teenager versus concerned parents that forms the crisis around sexuality, gender, class, criminality and violence Waters explores in many of his films.

The styling of the school sequences also acts as a rebuff to the Hollywood vision of delinquency seen in everything from Rebel Without a Cause and Blackboard Jungle (both 1955) to the musical framework of West Side Story (1961) and, the more sugar-coated fantasy of Grease (1976). It’s clear the class snitch informing on Dawn’s behaviour and demanding “I’m trying to get an education!” represented those targets the Dreamlanders were keen to mock. The sequence where Dawn, Chicklette (Susan Walsh) and Concetta (Cookie Mueller) discuss setting the school on fire and Dawn’s hatred of her parents is how Waters saw the triumph of the bad girls over the good girls. Waters wants you to root for the bad girls. This is all heightened by the bold production design by Peranio, the superb costuming and make-up by Van Smith and the wonderful bouffant hairstyles by Chris Mason.

The Christmas sequence is one of the best-remembered scenes in the film. When Dawn receives a pair of flat shoes as a present rather than the cha-cha heels she’s been longing for, her thwarted desire manifests as a violent rejection of cosy suburbia. The cha-cha heels are symbolic of her career trajectory, of how much of a bad girl she aims to be. Divine’s performance, as Dawn’s parents sing carols on the sofa and exchange gifts, is a brilliant essay of pent up rage and boredom. Dawn’s subsequent rampage, a direct assault on the ‘goodwill to all’ message of Christmas, that results in her mother pinned under the tree and her father chasing her out of the house, is conducted, in laughably incongruous style, with Dawn wearing a lime green shorty nightie and fluffy blue slippers. Fleeing, as jolly Christmas songs play on the soundtrack, she has a fateful encounter with the predatory Earl Peterson. Waters describes what follows as “the ugliest scene I ever did.”

Earl (also played by Divine, who later took great pleasure in responding to insults of “Go fuck yourself” by referring to this scene with “I’ve already done that”) has his wicked way with Dawn on a discarded mattress. This infamous Earl and Dawn coupling, witnessed by perplexed garbage men during filming on location at a dump in a Baltimore park, underlines the Divine/Harris Glenn Milstead character/actor divide and subtextually suggests Divine’s character is made pregnant by herself/himself. It’s a twisted version of the immaculate conception that shows Waters again deconstructing normative heterosexuality. He’s subverting the notion of the family unit in America of the 1960s in a Freudian, parodic flipside to the wholesomeness of the festive period.

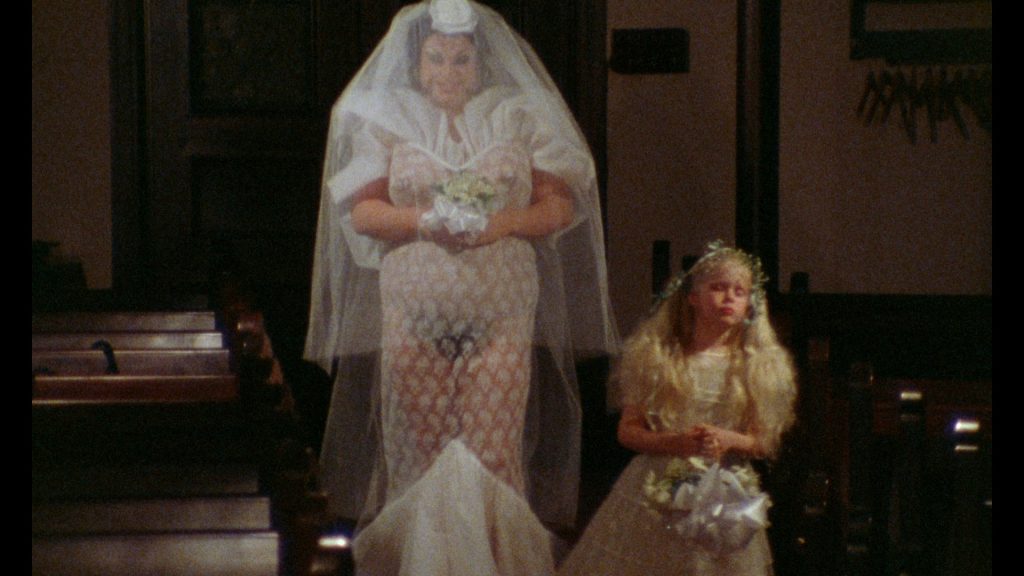

After Dawn gives birth to daughter Taffy (played by Susan Lowe’s three-day-old baby son, hidden up Divine’s skirt, covered in fake blood), the film moves to ‘Dawn Davenport —-Career Girl—-1961–1967’. It’s a wonderfully sleazy montage of Dawn as hamburger waitress, go-go dancer, street corner prostitute (filmed in Baltimore’s red-light district) and as one of a girl gang of petty thieves. In ‘Dawn Davenport —-Early Criminal —-1968’ we witness Dawn’s ‘parenting skills’. This involves dragging her daughter Taffy (now played by Hilary Taylor) upstairs to her bedroom where she is chained to the bed and hit with a car aerial. It wouldn’t surprise me if you’ve got your head in your hands at this point as the film’s child abuse nonchalantly collides with proto-punk drag and petty crime. However, Waters goes one better with the arresting introduction of Aunt Ida (Edith Massey), resplendent in her leather peek-a-boo S&M outfit. In a perverse reverse of the trauma of coming out, she tries to turn her hairdresser nephew Gater (Michael Potter) into a homosexual, suggesting “I’d be so proud if you was a fag” because the “world of a heterosexual is a sick and boring life.” However, Dawn, in Van Smith’s stunning see-through wedding dress design, marries Gater, much to Ida’s disappointment.

‘Dawn Davenport — Married Life —1969’ and ‘Dawn Davenport — Five years Later — 1974’ depict Dawn’s disastrous marriage. Sexual abuse, rendered with components of a tool kit, pushes Dawn to throw Gater out and instruct him to “go fuck a garage”. When Gater takes off to Detroit to join the auto industry, Ida’s emotional, gap-toothed, cleavage-framed breakdown has to be seen to be believed. In a nod to Waters’ own childhood fantasies simulating accidents using toy trucks and asking his parents to take him to junkyards, the maladjusted Taffy (Mink “for 14, you don’t look so good” Stole) plays at car accidents in the living room. She later tracks down and murders her father and, just to irritate her mother, becomes Hare Krishna.

Dawn’s bitterness over her failed marriage transforms her into a gloriously exaggerated version of Liz Taylor and the perfect candidate for the effete beauticians Donald and Donna Dasher (David Lochary, Mary Vivian Pearce), in their bid to topple societal norms with their ‘crime is beauty’ philosophy (influenced by Waters’ reading of Jean Genet). Although she briefly offends them by thinking they want her to make a porno, Dawn is chosen to model and represent Donald and Donna’s Dada art-terrorist project. Urged on by promises of stardom and celebrity, she injects liquid eyeliner into her veins, styles out her acid-ravaged face (courtesy of Aunt Ida’s revenge) and then runs amok during her trampoline act at a local nightspot. After tearing up telephone directories and, in homage to Russ Meyer’s Vixen (1968), smothering herself with fish, she turns a gun on the audience in the name of ‘art’ and declares “I’m so fucking beautiful, I can’t stand it myself!”

Dawn’s spiral into criminal fashion-terrorism pushes the film into outright surrealism, a Theatre of Cruelty maelstrom of deformity (Dawn’s acid burns and Ida’s hand replaced by a hook) eyeliner, Hare Krishna murder (Taffy is strangled), fish, Dawn desperately swimming across rapids to avoid capture by the police and lesbian love. One comes away with so much admiration for Divine, giving a performance that ultimately cemented his own celebrity and style. Kudos to him for going above and beyond during production, actually shooting up on camera, swallowing ipecac so he could projectile vomit, and shaving his head for Van Smith’s signature mohawk hair and makeup. What a trouper. While the film does tend to run out of steam, its final act is topped by a jaw-dropping, extraordinary sequence where Dawn, arrested and sentenced to the chair, gives her acceptance speech for the “equivalent to the Academy Award in her chosen profession of crime.” The eerie finale to this unique, bizarre, carnivalesque film is a disturbing frozen frame on Dawn’s face after tens of thousands of volts have coursed through her body.

USA | 1974 | 97 MINUTES | COLOUR | 1.66:1 | ENGLISH

writer & director: John Waters.

starring: Divine, David Lochary, Mary Vivian Pearce, Mink Stole, Edith Massey, Cookie Mueller, Susan Walsh & Michael Potter.

I’m indebted to the following sources: John Waters, Shock Value (Running Press, 2005) • Robert L Pela, Filthy —The Weird World of John Waters (Alyson Books, 2002) • Chris Holmlund, Female Trouble—Queer Cinema Classic, (Arsenal Pulp Press, 2017) • Bernard Jay, Not Simply Divine!, (Virgin Books, 1993) • Robert Maier, Low Budget Hell: Making Underground Movies with John Waters (Full Page Publishing, 2008) • James Egan (ed), John Waters Interviews (Univ. Press of Mississippi, 2011) • Ed Halter, ‘Female Trouble—Spare Me Your Morals’, (Criterion Collection, 26 June 2018) • David Chute, ‘Still Waters’, (Film Comment, May-June 1981)