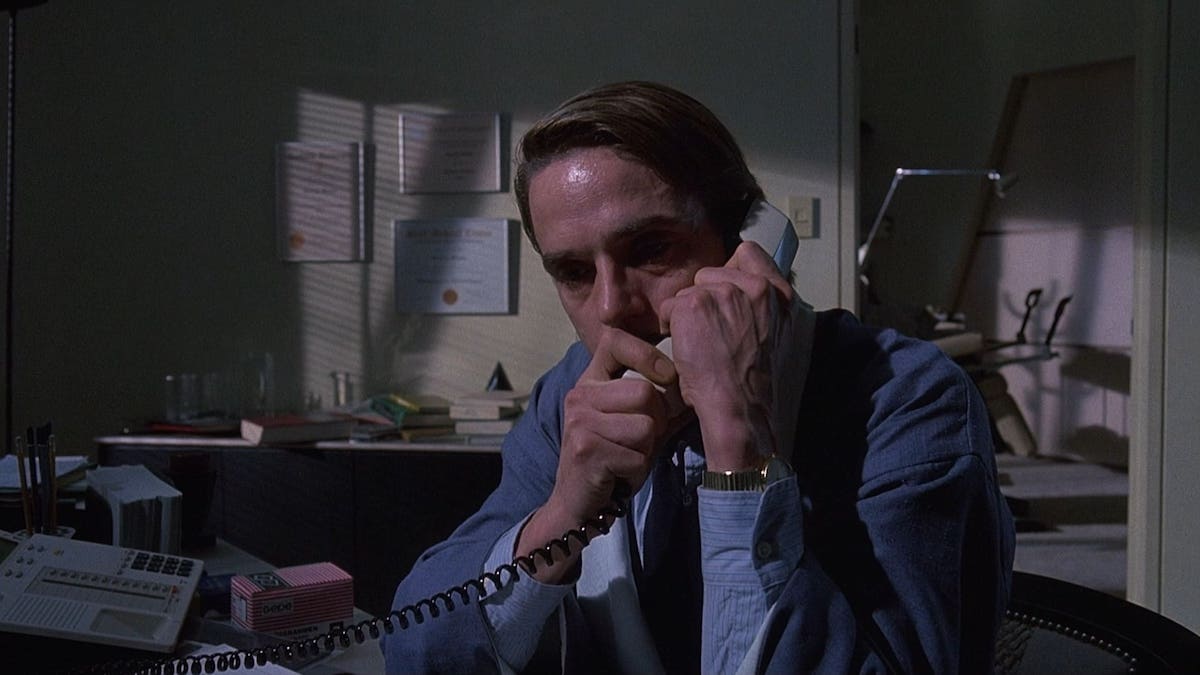

DEAD RINGERS (1988)

Twin gynecologists take full advantage of the fact that nobody can tell them apart, until their relationship begins to deteriorate over a woman.

Twin gynecologists take full advantage of the fact that nobody can tell them apart, until their relationship begins to deteriorate over a woman.

David Cronenberg’s Dead Ringers is a strange tale, but it’s even stranger when you realize it’s based on the true story of identical twin gynaecologists Stewart and Cyril Marcus, who were found dead in Cyril’s Manhattan apartment in July 1975, at the age of 45. The cause of their untimely deaths remains uncertain.

Stewart is believed to have died between 10–14 July, but Cyril was seen walking about in the city after then, so he’s suspected to have died between 14–17 July. Although their addiction to barbiturates is considered to be the main factor in their deaths, rumours of mental illness have led to theories of a suicide pact. Whatever happened in the final days of their lives, their deaths were incredibly peculiar.

Cronenberg, who had just finished directing the Kafkaesque nightmare The Fly (1986), was drawn to the strangeness of the Marcus twins’ real-life story. It provided the plot points necessary for a chilling psychological horror film, but Cronenberg added his traditional phantasmagoria.

Dead Ringers begins as a discomfiting portrait of the unhealthy codependency of two twin brothers. Given the director’s history in creating macabre, psychological terror—often with a touch of body horror and technological angst—one could have expected a harrowing depiction of the fraternal bond. Instead, the plot gently meanders into the territory of a sad family drama. While haunting in its own tragic way, one can’t help but feel as though the story could have been taken in more interesting directions.

The film commences with the twin brothers as prepubescent little boffins. Elliot and Beverly Mantle stroll around the neighbourhood, discussing sex and science just like any normal children would. They both court the same woman, presenting her with the offer to have sex with them in their upstairs bathtub in order to settle their theory about how fish reproduce. Unsurprisingly, they’re rudely rebuked. One can’t help but postulate that this is exactly what Cronenberg would have been like as a child: innocently concerned with inveigling women to fornicate with him in bathtubs under the guise of it all being for the sake of science… and fish too, of course.

When we cut forward a few decades, the identical twins are creating industry-defining technology, to the chagrin of their professors. These two seem destined to become superstars of the gynaecological world, innovating the field through ground-breaking research and unconventional—yet effective—technology. When the Mantle twins first encounter Claire Niveau (Geneviève Bujold), a famous actress desperate to have children, they’re both struck by how aberrant her biology is: she has a trifurcated cervix, a strange, previously unseen mutation.

Elliot takes Claire out on a date, though she’s led to believe that he’s actually Beverly. For the twins, this is just another day in the gynaecological office: Elliot seduces the patients, and then Beverly takes over when his arrogant older brother becomes bored. Due to their uncanny similarity, no one can ever tell the difference. However, Elliot becomes concerned when he realises that the pair of them are wading into unknown territory: Beverly’s fallen in love with Claire and wants his controlling brother out of the picture.

Much like the two primary protagonists, the film appears to be one seamless whole but is really split into two distinct parts: the horrifying and the dramatic. The pace is slow, creating an unnerving atmosphere through the seedy exploits of the brothers and their strange relationship. It’s soon apparent that the connection Elliot and Beverly have is an unhealthy form of co-dependency. They share everything: the women they sleep with, their apartment, and even their careers. The success of one means the success of the other and it’s equally true of failure. It doesn’t seem quirky or amusing, nor does Cronenberg intend it to be; instead, it comes across as the disturbed manifestation of the Mantle twins’ confusion regarding where one of them ends and the other begins.

Early on, Elliot reveals himself to be more socially competent than his shy, introverted twin. Naturally, he is also the more aggressive and domineering of the two. When Beverly refuses to share intimate details about his erotic tryst with Claire, Elliot becomes indignant, pushing his dinner aside and sternly informing Beverly “You haven’t had any experience until I’ve had it too.”

Here, we’re provided insight into how this pair of sophisticated, educated socialites are actually severely stunted in terms of their psychological development. They are, as Ronald David Laing has termed it, ontologically insecure. Laing has described ontological insecurity as the anxiety that surrounds a person when they believe their position in the world is vaguely defined and constantly at risk, that their personal identity is threatened and their autonomy is always in question. This describes the Mantle twins pretty aptly.

Though Elliot presents himself as highly competent and, above all else, autonomous, the older twin finds himself insecure and deeply anxious when in conflict with his acquiescent brother. He sees the pair of them as a unit, a singular entity. He claims that they are “perceived as one individual”, but it’s arguable he does this more than anyone else. The discord that occurs between the two over Beverly’s relationship with Claire represents internal turmoil in both of them at the level of the soul.

Elliot wishes that they could be together forever, both as a paragon of gynaecological innovation and as charming ladykillers. This frequently takes disconcerting forms: when he hires two escorts, who are also identical twins, he instructs them to call him by different names. “I’d like you to call me Elly. And you, Mimsy, you call me Bev.” No matter how high he flies, he considers it all for nought if his brother is not by his side.

These twins have always been close, both literally and figuratively. The fact that they don’t still share a uterus almost appears to be an irreparable loss, a wound that they cope with through various means. Beverly blithely dismisses their sharing an apartment together as the result of them having the same taste in Italian furniture, but it could just as equally be interpreted as an attempt to return to a pre-natal state where they shared a womb, the moment when they were at their closest. There are other examples of how the Mantle twins appear to act out infantile desires unconsciously. The fact that they share women could be seen as the pair replacing the first woman they shared in their life: their mother. In the sex scene with Beverly and Claire, when she rolls her head back in ecstasy, Beverly buries his head between her breasts. Needless to say, Freud would probably have a lot to say about that.

Perhaps psychoanalysing the two protagonists would be misleading if another director were at the helm, but with Cronenberg’s history as a filmmaker—one need only look at the likes of Shivers (1975) and The Brood (1979) to see his penchant for dramatizing subconscious fears—it appears to be the only logical interpretation. We’re provided with the first glimpse of quintessential Cronenberg when Beverly wakes up in the middle of the night, with Claire on his right and his brother on his left, physically attached to him by some alien-looking, pulsating flesh. Claire offers to separate them: she sinks her teeth into their bond and rips it apart. For fans of the Canadian auteur’s classic work, this seems like the moment when the madness, psychosis, and horror are about to kick into second gear.

However, what happens is just the opposite. At around this point in the story, there’s a tonal shift: Dead Ringers goes from a dark, brooding psychological horror to the final act of a Shakespearean tragedy and the focus of the story turns to the downfall of the dynamic duo. With Claire gone, Beverly begins using drugs more and more frequently to cope. As he becomes increasingly unstable, the Mantle twins are practically expelled from medical practice. With frightful suddenness, they find themselves cast adrift. As though he cannot stand the thought of his brother suffering through things alone (a stark reminder of how their equilibrium has been completely ruptured), Elliot follows Beverly into the world of barbiturate abuse. He soon finds himself just as lost. As tormented exiles, they wander helplessly from prestigious award ceremonies into the lonely clutches of drug addiction.

In a short time, it appears as though there is no light at the end of the tunnel. The two brothers are rendered children once again, eating cake and weeping at the heart-breaking lack of ice cream. Though you probably found yourself disgusted with their initial turpitude and unscrupulous treatment of those around them, watching them in such a pitiful state truly is gut-wrenching. In their utter desolation, it becomes difficult not to sympathise. This is both a testament to Irons’ incredible performance as well as the unwavering direction from Cronenberg behind the camera.

Doomed to descend into addiction together, the symbolism of the conjoined twins is never more apparent: it is as though Beverly has contaminated both of their bodies through his substance abuse. The true story of Chang and Eng Bunker, Siamese-American conjoined twins who became two of the most widely studied people of the 19th-century, is referenced by Elliot as he laments the sorry fate that has befallen his brother. At this moment, he seems cognisant of the fact that they are both on their way out—after all, how else could they make this final journey if not together?

However, while tragic, it’s undeniable that the film lacks the kind of impactful, shocking finale that a classic Cronenberg film normally delivers. Though we nervously anticipate the spiral into madness à la Videodrome (1983) or The Fly, filmed as a disorientating nightmare, there is instead a spiral into drug abuse, depicted with realism that is uncharacteristic of Cronenberg’s other work from this time period. Personally, as a fan of Cronenberg, I was disappointed he didn’t go full Cronenberg; it felt as though he had squandered a marvellously creepy set-up by not delving headlong into some disturbing science-fiction/psychological terror. What could have become an all-time classic of the horror genre ends up being initially discomforting, but ultimately just plain old sad.

Perhaps the director wanted to steer away from such grotesque depictions of our deepest inner fears. Maybe he had become cautious of turning into a caricature, so decided to omit a monstrous descent into freakish territory. But then again, his next film was Naked Lunch (1991), which is the epitome of his stylised fever dreams. Unfortunately, there’s an argument to be made that Cronenberg’s imaginings of a disturbed psyche are his most compelling trademark as a director; some of his other films that I listed all serve as stellar case studies where he demonstrates his capacity for depicting Freudian fears and existential dread in original ways.

With all of that being said, there is still something that brings me back to this film. Perhaps it’s the very believable depiction of a rather unsettling, insidious co-dependency. Or maybe it’s the fantastic acting, or the stark depiction of loneliness that each of the three protagonists all feel. Their malaise seeps through the screen and watching their attempts to quell their ennui is truly haunting. Though Cronenberg doesn’t go over the top, his measured approach to the story creates an atmosphere of beautiful sorrow akin to that of Greek myth. In doing so, he turns it into one of his best films, even if the deviation from his normal style may disappoint some fans. Overall, Dead Ringers is a superb film, one that defies formula and becomes something entirely unique—much like the story that inspired it.

CANADA • USA | 1988 | 115 MINUTES | COLOUR | ENGLISH

director: David Cronenberg.

writers: David Cronenberg & Norman Snider (based on the novel ‘Twins’ by Bari Wood & Jack Geasland).

starring: Jeremy Irons, Geneviève Bujold, Heidi von Palleske, Barbara Gordon, Shirley Douglas & Stephen Lack.