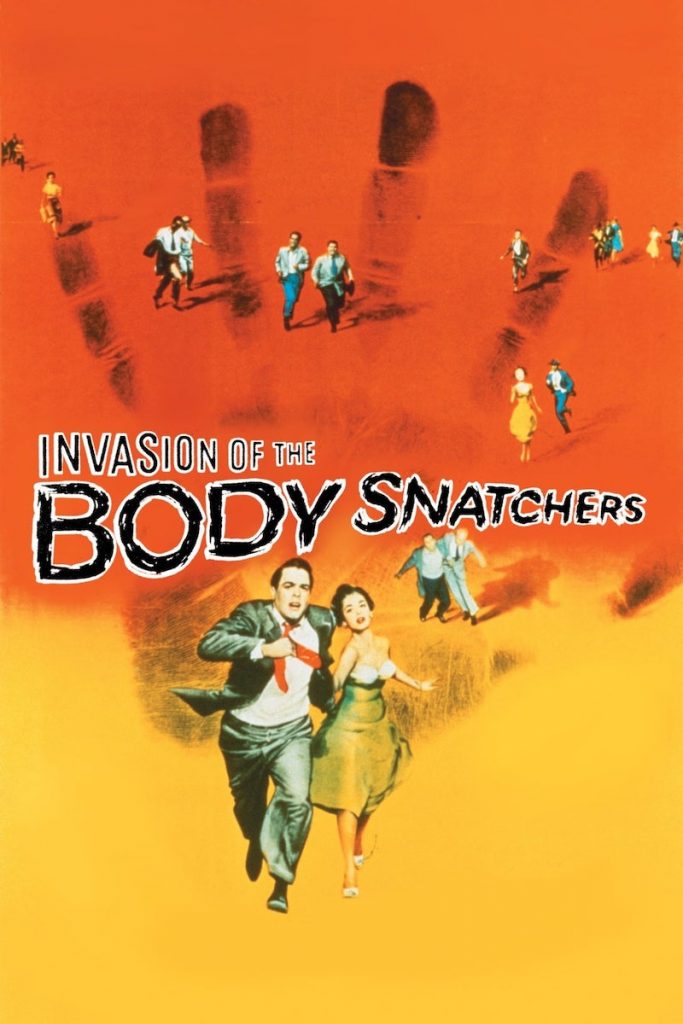

INVASION OF THE BODY SNATCHERS (1956)

A small-town doctor learns that the population of his community is being replaced by emotionless alien duplicates.

A small-town doctor learns that the population of his community is being replaced by emotionless alien duplicates.

Shortly before the long chase sequence that leads Invasion of the Body Snatchers to its climax, Dr Miles Bennell (Kevin McCarthy) and his recently reacquired girlfriend Becky (Dana Wynter) watch warily through the window of his medical office in downtown Santa Mira, California. In the town square below, citizens silently converge, coming together in a shared mission that threatens to destroy Kevin and Becky, the town, and likely the world. They’re tidy and efficient but unmistakably resemble zombies in their single-minded purpose.

Invasion of the Body Snatchers was “the first postwar horror film to locate the monstrous in the normal”, as horror and sci-fi film historian Barry Keith Grant wrote, and those abnormal townsfolk in the square typify it. Don Siegel’s film is not generally one where specific events are terrifying—not even when a replicant woman is found vampire-like in a large box from which she’ll soon rise to kill. But the cumulative effect of them gives a real sense of desperation and fear, and by the end there’s a rawness to Miles and Becky’s panic that’s far more frightening than any number of blood-soaked monsters.

Based on Jack Finney’s 1955 novel The Body Snatchers (first serialised in 1954), the movie starts at a hospital where we see a distraught Miles protesting to sceptical doctors that he’s not crazy. This prologue, and a similarly brief epilogue, was added late in production at the behest of the studio, who feared Siegel’s ending would be too depressing for audiences. What Siegel intended is therefore presented as a flashback sandwiched between them.

It begins with Miles returning to Santa Mira after an absence, and immediately noticing small signs of weirdness in the town: a young boy fleeing from his mother, a flourishing roadside produce stand unaccountably closed. Already the groundwork is laid for later revelations. Several of Miles’s patients, among them Wilma (Virginia Christine), start making strange claims that family members have been replaced by lookalikes. “There was a special look in his eye,” Wilma says of her Uncle Ira. “That look’s gone. There’s no emotion.”

Miles’s psychiatrist friend, Dr Dan Kauffman (Larry Gates), insists it’s rationally explainable and nothing more than an “epidemic of mass hysteria” caused by “worry about what’s going on in the world”. The lack of specificity about exactly which aspects of the world are worrying has made Invasion of the Body Snatchers fertile ground for interpretation.

But another friend, Jack (King Donovan), soon finds evidence there’s a bizarre physical explanation: the people of Santa Mira are indeed being replaced by doppelgängers. One by one they succumb, until apparently only Miles and Becky remain as their true selves.

Invasion of the Body Snatchers has several powerful scenes, and at least one—where Wilma is revealed to be a replicant, or “pod person”—is genuinely chilling. Siegel’s original ending, with Miles running along a crowded highway ranting like a madman about the end of the world, is shocking too; and Becky’s slip-up where she reveals herself to be a human being rather than an emotionless pod person (she cries out at a dog dashing in front of a truck) provides a real frisson of anxiety.

It would, of course, also have been more impactful to 1950s audiences for whom this story was unfamiliar. For modern audiences, meanwhile, there are some great period California locations. But individual moments and a few nice directorial touches from Siegel—for example, the noirish deep shadows, the composition of shots where Miles and Becky are hiding behind a door with a small window, the energetic reverse tracking in the final chase, the ominous poster for “Mirroir Noir” suggesting an inversion of normality—all come second to the overarching thrust of the story, and for the most part it’s filmed in a straightforward manner.

The cast are competent and convincing, if unremarkable, and the film benefits from none of them being big names. (It would have been far harder to believe in Miles’s plight if he’d been played by, say, Joseph Cotten as once intended). Carmen Dragon’s score, similarly, is mostly mundane though it can be unsettling and effective on occasions, most notably at the opening of the chase sequence.

Altogether, then, Invasion of the Body Snatchers is very much a film about what is depicted rather than how it’s depicted. The big question is what it all means; beyond recounting a rather far-fetched apocalyptic sci-fi scenario (and the last transition of a human into a pod person is famously baffling, since it seems to break physical laws that have been respected by the film up to that point), what is Invasion of the Body Snatchers trying to say?

Seeing the pod people as a metaphor is almost irresistible. In reality, this might not have been intended by the filmmakers in anything but the most general sense. Siegel said:

… many of my associates are certainly pods. They have no feelings… The pods in my picture and in the world believe they are doing good when they convert people into pods… It leaves you with a dull world, but that, my dear friend, is the world in which most of us live.

But that hasn’t stopped the film becoming the object of multiple interpretations, in which the pod people could represent communists—like the giant ants of Them! (1954)—or they could stand for the inhumanity and repressiveness of Senator Joseph McCarthy’s anti-communist crusade… rendering the lead actor’s surname somewhat ironic!

They might simply be symbols of 1950s conformity. “You’re reborn into an untroubled world”, a pod person explains to Miles. One of their most interesting features is that they’re aware of their nature, and enthusiastic about it. “Where everyone’s the same?” he responds dubiously.

Or perhaps the movie’s talking about tranquillisers (which started to be widely prescribed in mid-1950s America). Or perhaps, as Grant says, we shouldn’t look for such a specific, literal explanation. “it is above all a centrist nostalgic lament” about changing society. Not so much homeland insecurity, then, as things not being what they used to be.

That’s persuasive, but still—despite the impeccably liberal credentials of veteran producer Walter Wanger, who was heavily involved with shaping the film—a reading of the pod people as communists seems credible. The erasure of family attachments in favour of the wider society, the highly organised way fresh pods are distributed in the town square to spread pod-ism further, the elimination of private enterprise (at least two businesses are seen closing, while a farmer’s greenhouses are turned over to mass production for the common good) all point to the pods being Reds rather than McCarthyites.

Whatever they do or don’t represent, though, the disturbing possibility they hint at is much more fundamental, and explains why the film’s ensured as a cult classic long after the political circumstances changed. As film historian Carols Clarens (author of An Illustrated History of the Horror Film) wrote:

The ultimate horror in science fiction is neither death nor destruction but dehumanisation, a state in which emotional life is suspended, in which the individual is deprived of feelings, free will and moral judgment… This type of fiction hits the most exposed nerve of contemporary society: collective anxieties about the loss of individual identity, subliminal mind-bending, or downright scientific/political brainwashing.

Or, as Miles puts it: “Only when we have to fight to stay human do we realise how precious it is.” It’s perhaps significant that near the end, he and Becky are forced to hide out in a cave, reduced to the state of the earliest humans.

Released in the US on a double bill with the now little-known The Atomic Man (renamed Timeslip in the UK), Invasion of the Body Snatchers was shot in only three weeks on a budget greatly reduced from the original proposal, and received the sniffy critical reception that such pictures often did. The Los Angeles Times, for example, noted “suspense and some sharp acting” but opined that it “degenerates into a rather trite, hectic chase with a thoroughly unresolved ending.”

That ending, insisted on by the studio Allied Artists and sometimes compared to the framing device imposed on The Cabinet of Dr Caligari (1920), seeks to add an optimistic indication that the pod people would soon be defeated (as indeed they are in Finney’s novel) and contrasts with the far bleaker conclusion envisaged by Siegel, Wenger, and their writer Daniel Mainwaring.

Some have tried to interpret it and the prologue as sneakily subversive, implying the doctors to whom Miles protests his sanity are themselves pod people, but in honesty it’s difficult to see them that way—even if one of the breathless original poster tagline, “Incredible, insatiable cosmic hordes take over every living human!”, does suggest it. The epilogue in particular feels stuck-on, and it’s little surprise that both it and the prologue were cut when Crystal Pictures bought the rights to Invasion of the Body Snatchers and rereleased it to cinemas in the 1970s.

But while the studio-mandated ending doesn’t work, it didn’t do much to detract from the film’s power either, and nor did the cheapo transfer to the SuperScope format, which involves shooting in a conventional ratio rather than in widescreen and then blowing up the image at printing stage. (A loss of definition can result, though it is not obvious in this case, at least not on a small screen.) Invasion of the Body Snatchers was a commercial success and it had its early fans, not least renowned critic Pauline Kael. Despite harrumphing that it “employs few of the resources of the cinema”, she frequently booked it for late-night shows when she was managing a movie theatre. It was eventually admitted into the National Film Registry.

Siegel, who had started out more than a decade earlier as a junior director on movies like Casablanca (where he shot the opening montage) eventually went on to make a series of prominent films including Dirty Harry (1971) and The Shootist (1976). His brainwashing thriller Telefon (1977) bears some thematic resemblance to Invasion of the Body Snatchers too.

And, of course, one of the bit-part players in Invasion of the Body Snatchers, a certain Sam Peckinpah, also became a legendary director. Peckinpah claimed, controversially, to have substantially rewritten Invasion of the Body Snatchers, though his contribution was likely very minor.

More than through individual’s careers, though, the influence of Invasion of the Body Snatchers has been felt in other works for the screen. It’s been remade overtly three times—under the same title by Philip Kaufman in 1978, as Body Snatchers (1993) by Abel Ferrara, and as The Invasion (2007) by Oliver Hirschbiegel. It also strongly influenced countless other movies, from Seconds (1966) to The Stepford Wives (1972) and Get Out (2017), as well as much of the zombie genre. There’s even a reference in Gremlins (1984).

For a film whose makers insisted, or liked to pretend, that it was nothing more than a fun alien-invasion fantasy, that’s an impressive legacy. And for all its lack of slickness and occasional clumsiness, it remains a movie that leaves a lasting impression on audiences.

Whatever Invasion of the Body Snatchers is trying to tell us, it disturbs on a level far deeper than the narrative, on a level where our humanity and our trust in other people feel threatened. It may be a modest film in terms of running time and budget and production values, but it takes us to some profound places.

USA | 1956 | 80 MINUTES | 1.85:1| BLACK & WHITE | ENGLISH

director: Don Siegel.

writer: Daniel Mainwaring (based on ‘The Body Snatchers’ by Jack Finney).

starring: Kevin McCarthy, Dana Wynter, Larry Gates, King Donovan & Carolyn Jones.