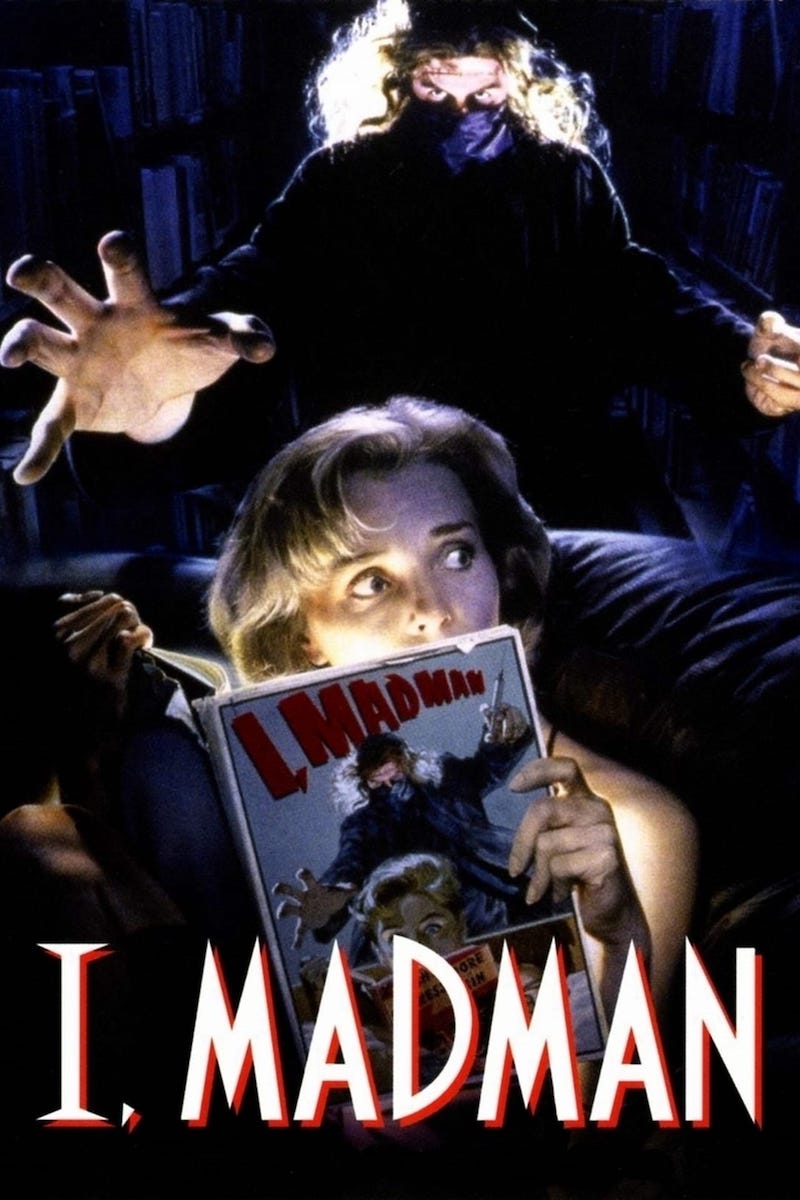

I, MADMAN (1989)

A bookshop clerk finds that an insane and murderous doctor from one of the store's horror novels has come to life.

A bookshop clerk finds that an insane and murderous doctor from one of the store's horror novels has come to life.

There are cult films that become huge over time, gradually accruing legions of loyal fans until they go mainstream. Others remain cult, loved by a handful of acolytes, but never discovered by the majority. It’s a mystery to me how a film as good as I, Madman remains in the latter category. Ever since renting it on VHS, back in the early-1990s, I’d been anticipating a sequel… which never happened because it was considered a flop.

A year after it bombed at the box office, it went on to win the Grand Prix at the 1990 Avoriaz International Festival of Fantastic Film, a much-revered accolade that must have been a salve for director Tibor Takács (The Gate). Past recipients had included Stephen Spielberg, Brian De Palma, David Lynch, James Cameron, David Cronenberg, Jim Henson, and Frank Oz.

I suppose it was difficult to market, being a little out of step with the late-1980s horror audience’s appetite for more and more gore, with less and less story. But there is some gore in I, Madman… just nothing gratuitous. However, there’s definitely a story; an unusually well-thought-out and cleverly structured one at that. What it lacks in visceral bloodshed is more than made up with its psychologically disturbing concepts and three ‘nested’ narratives. Now that may make it sound pretentious, but it isn’t and at no point does it forget to entertain us.

The opening scenes of I, Madman lead audiences to expect a very different film to what they’re about to get. It starts out in a ‘very comic’ book version of the 1950s with stilted dialogue worthy of a David Lynch film. Dr Kessler (Randall William Cook), looking sinister in a long coat, black beret, and muffler, leaves his hotel and, in his absence, the manager (Bob Frank) decides to check the room of this “weirdo and troublemaker” because there’ve been complaints of animal noises. What he finds is something between a mad scientist’s lab and a filthy freakshow, with pickled specimens, cockroaches, and excrement on the floor. As he’s about to leave in disgust, he hears the noises for himself… coming from a large travel chest… and as he approaches a child’s voice comes from within. What he releases from the chest is indeed a child, of sorts, but a monstrously inhuman one.

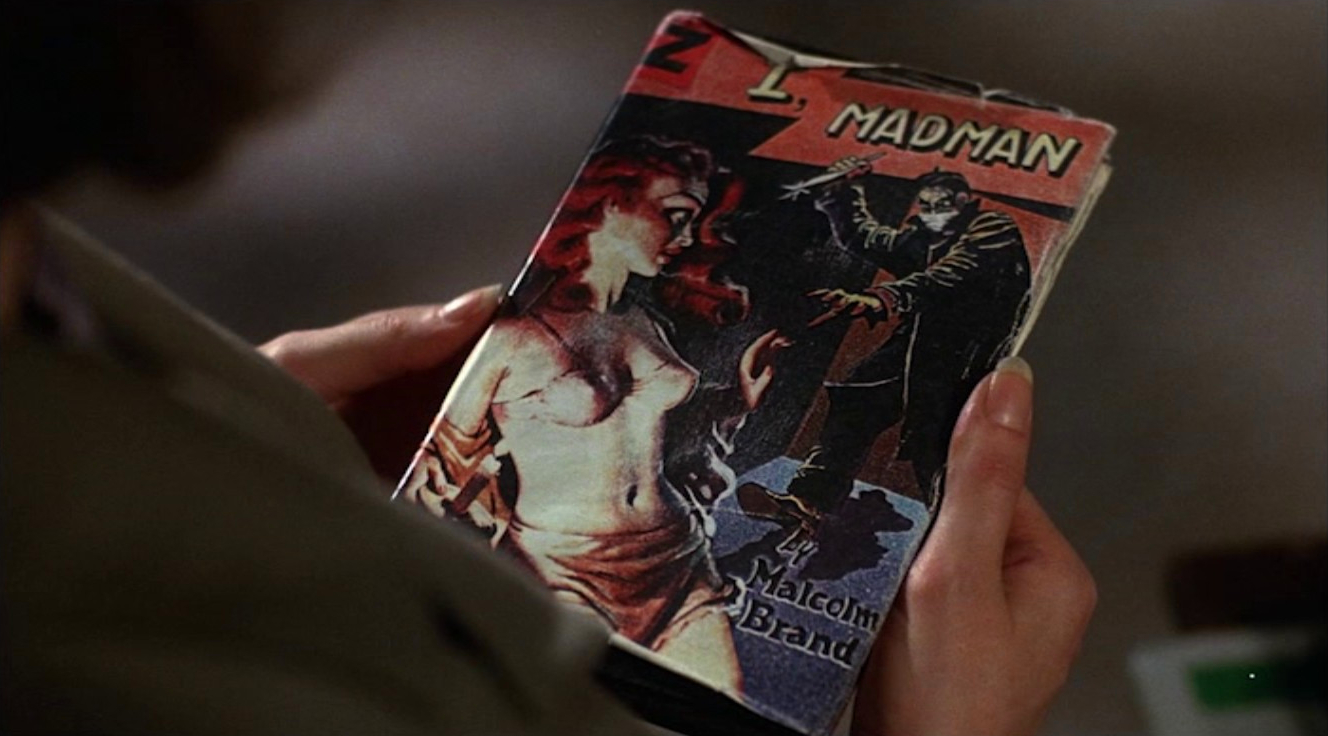

But that ‘reality’ is different from the one inhabited by Virginia (Jenny Wright) who works at a second-hand bookstore in modern-day Los Angeles. She’s been reading a rare book with the inspired title Much of Madness, More of Sin, that was delivered as part of a consignment from the estate of the author Malcolm Brand, presumed dead. She’s an avid reader but this book affects her on a deeper level than any other.

So, this is the blurb from that fictional book’s flyleaf: “Tortured and ridiculed by the scientific establishment for his investigations into the creation of superior lifeforms, noted zoologist Dr Erlan Kessler continues his experiments in the cloaked secrecy of his basement laboratory. Finally, after years of failure and frustration, he manages to successfully mate his own seed with an egg excised from the ovaries of a jackal and plants it in the womb of an unwitting human surrogate…”

I’ll just leave that here and move on.

Screenwriter David Chaskin started out with a story about a cursed book, some sort of magical grimoire that has the power to call forth demons. That may not sound very original, and he’d already explored his interest in metafiction, where one reality seeps into another, in his script for A Nightmare on Elm Street Part 2: Freddy’s Revenge (1985). Don’t worry, I, Madman is by far the superior film! Instead of an ancient black magic book, inspiration struck and he decided to make it a ’50s pulp novel, bringing in all the lurid imagery suggested by that bygone genre. And instead of a ghost that comes to life through dreams, we have an author who’s somehow written himself into the pages of his novels and can be brought into reality by the imagination of a captivated reader. Interestingly, this was written 15 years before Cornelia Funke wrote her 2003 best-selling novel Inkheart.

Chaskin’s second screenplay had been The Curse for Transworld Entertainment and, luckily, one of the executive producers, Moshe Diamant, came to him with a commission for another script whilst it was in post-production. Otherwise, they may have thought twice about hiring him again! The Curse was supposed to be a fairly faithful adaptation of H.P Lovecraft’s The Colour Out of Space. It had some potential for sure and even had the legendary Italian horror director Lucio Fulci as associate producer, but Chaskin had a hard time retaining his initial vision. Between them, David Keith (an actor who was trying his hand at directing), and producer Ovidio G. Assonitis pulled the script apart and completely rearranged it. Chaskin’s flashback structure was reordered into a traditional linear narrative that also skipped much of the planned story arc! The result was both a creative and a commercial disaster. But by the time the distributors realised this, Chaskin was already onto the second draft of his I, Madman script.

Hungarian director Tibor Takács, who’d just had a surprise success with his low budget high-earning third feature The Gate (1987), suddenly found himself being offered an array of projects. Among them, it was one brought to him by producer Rafael Eisenman that caught his eye: I, Madman. Although it came with another low budget, the script was exactly what he was looking for. He saw in Chaskin a kindred spirit. They both had fond memories of watching The Twilight Zone and Outer Limits as kids and shared a love of classic black-and-white monster movies; sensibilities they successfully weaved into this film.

In contrast to his experiences on Elm Street and The Curse, Chaskin described the production process of I, Madman as a “delight” and worked closely with Takács from the moment he was brought on board. Because of the recent success of The Gate, there was very little interference from the studios and they enjoyed almost total creative freedom, albeit with the budgetary restrictions. The lack of funds can only be glimpsed here and there and, for the most part, the film looks a lot more solid than many of the more expensive ’80s horrors. Some of the credit for this certainly goes to the director of photography Bryan England, who wanted to light it like the ’50s classics of George J. Folsey—the cinematographer behind Forbidden Planet (1956).

Takács realised that good make-up effects were called for and needed the monstrous jackal-boy to make an appearance. Randall William Cook had brought the nightmarish hell spawn creatures to life for The Gate. He’d also been responsible for the aliens in Laserblast (1978), the animation effects in John Carpenter’s The Thing (1982), and the hell-hounds in Ghostbusters (1984). But I, Madman didn’t have the budget and Takács had to think of another way to entice him to join the production. He knew Cook harboured acting aspirations and had long wanted to play a classic movie monster like the ones fleshed out by his hero, Lon Chaney. So when offered the chance to appear as the titular Madman, Cook jumped at the chance!

The results are admirable. Cook discussed what he was planning with his mentor, Ray Harryhausen, who thought it over-ambitious given the time and money constraints. Reportedly, he was suitably impressed when shown the final results. The stop-motion sequences for the jackal-boy monster are clearly animation but do have the magical Harryhausen vibe that Cook was looking for. They only happen when reality is breaking down, so their unreal feel helps rather than hinders.

The prosthetic make-up effects are also surprisingly good. They’re done using the old-school method favoured by Italian horrors of the ‘80s, which is basically sculpting in plasticine and sticking the pieces onto the actors. The illusion is completed with skilful painting along with sympathetic lighting and editing. And those elements come together impressively. It’s one thing to make a mutilated corpse look convincing, but quite another to act through the patchwork of a plasticine mask. Cook does an excellent job as the undead Kessler, relying almost totally on his eyes and creepy body language. There’s an undeniable Dr Phibes vibe going on, but apparently he was aiming for a Phantom of the Opera-style villain… only less sympathetic.

The entire cast all turn in committed performances, but Jenny Wright stands out in the dual lead as 1980s Virginia and 1950s Anna Templar, the fictional heroine of Malcolm Brand’s lurid second novel I, Madman. Takács was more than happy with what he described as her “interesting choices” in how she played the part. Wright was a bit of catch for the lead, having just turned in a breakthrough role for Kathryn Bigelow in the innovative vampire movie Near Dark (1987). Here, she plays a much more quirky, vulnerable, not to mention effortlessly sexy, character.

Virginia’s police-detective boyfriend, Richard (Clayton Rohner), is more of a classic handsome hero type. He’s easy on the eye and slow on the uptake when murders from the books she’s reading start to happen in real life, seemingly at the hands of a crazed serial killer who mutilates each of his victims in strange and specific ways…

Y’know in thrillers and horror films when they don’t go to the police because “they’ll never believe it, anyway”? Well, here she does sensibly tell all to the cops when she witnesses a murder, giving them every detail she can:

He thinks I’m this actress named Anna Templar, from the book… He cut off his hair, his ears, his lips and his nose—everything! And now he’s gonna go around and take things from other people so he can graft them onto his own face… because he thinks it will please me.

Y’know what? They don’t believe her, anyway.

See what I mean by ‘psychologically disturbing concepts’, though? So many delicious subtexts to explore! It opens discussions about the legacy of the war and its influence on so-called body-horror. Gender issues are explored relating to ownership of the female reproductive system, and how a patriarchal society punishes women who seek autonomy. There’s even a lovely lighthearted deconstruction of the themes explored in Roland Bathe’s 1967 essay The Death of the Author!

The horror element is mainly in the disconcertingly outre ideas with the gore used sparingly, partly so the lack of cash didn’t show on the screen but mainly because it’s not necessary. Late ’80s gore-hounds, expecting a run-of-the-mill slasher movie, would’ve been disappointed and the marketing may have been misleading. But after the glut of gore, a return to the sensibilities of classic horror like Mad Love (1935) and Eyes Without a Face (1960) was most welcome.

All in all, this is a highly satisfying viewing experience that wrong-foots its audience right from the start and keeps hooking us in with little twists and surprises. There are some beautifully poetic moods too. Although clearly chilly, Virginia enjoys reading with the window open…. so she can enjoy the sound of a piano drifting up from the music shop across the street. The performances are fresh, intriguing and as believable as they can be in the context. Some added appeal comes from being shot on location in a vanished Los Angeles over the festive season from November 1987 to January 1988. So, it accidentally becomes a great alternative Christmas movie as well as being absolutely ideal for Halloween!

1989 was a good year for left-field horrors with the likes of Santa Sangre, Shocker, The Church, Warlock, Puppet Master, Parents, Society, Tetsuo The Iron Man, and certainly I, Madman remains as deserving of the genre fan’s attention as any. One feels that if it had been re-released with more sympathetic marketing after its huge success on the festival circuit, it may have upped its box office taking to more than its meagre $150k. It did get a home video release in 1990, but instead of capitalising on its recent award, it was retitled Hardcover! An unsympathetic full-frame DVD release then came along in 2003, but it was finally given some respect with a remastered 1.85:1 Blu-ray boasting great extras (including an audio commentary with Tibor Takács and Randall William Cook) from Shout! Factory in the USA and Canada. That was 2015, but Europe only got a sneaky 2018 budget DVD release with no extras from NSM Records (it’s dubbed in German, but with an option for original English-language track). Alas, no news of a UK Blu-ray version as yet.

director: Tibor Takács.

writer: David Chaskin.

starring: Clayton Rohner, Jenny Wright, Randall William Cook & Stephanie Hodge.