Hollywood Meets Hong Kong: The Stunt Performers Who Changed American Action

With Extraction 2 getting ready to drop (the sequel to what was then the highest-streaming Netflix film ever), star Chris Hemsworth is back in the spotlight for something other than his role as Thor. But Hemsworth would likely be the first to admit the real star of Extraction (2020) was director/cameraman/stunt coordinator/actor Sam Hargrave. With Extraction 2, Hargrave is confirming his place in the pantheon of new action film directors who’ve forced open the sometimes miserly gatekeepers of film criticism.

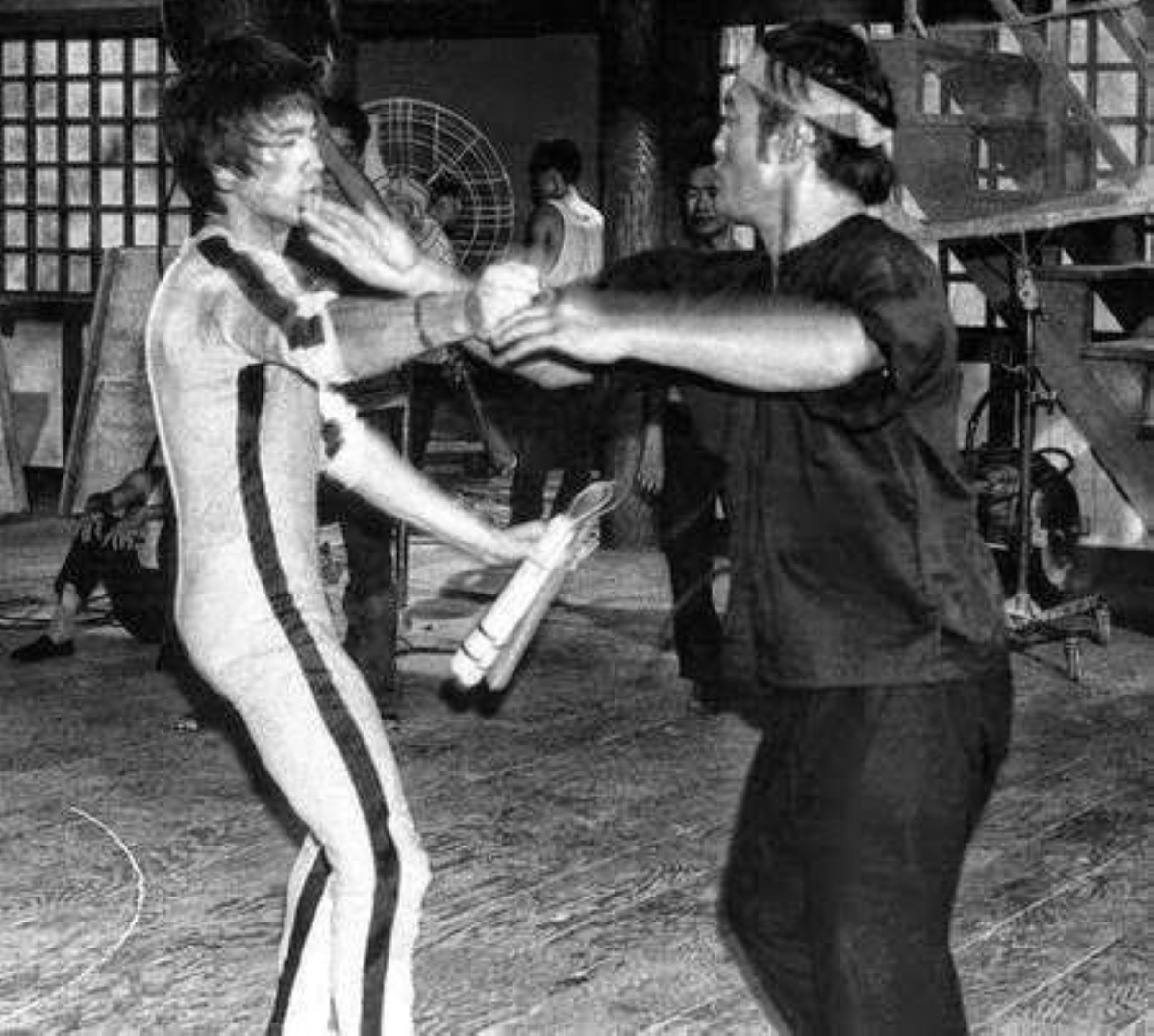

Even film snobs who might look down their nose at an action film that takes itself seriously have been forced to praise the phenomena of The Matrix (1999), John Wick (2014), and other taut actioners of late. And no offence to Keanu Reeves, but that’s less to do with him and more to do with those behind-the-scenes. Intense action scenes, paired with cameras capturing what the performers are doing and not hiding it with edits. Something Jackie Chan figured out a long time ago is that if you really do the work, and you let the audience see, they’ll show up. It’s been slow-going for Hollywood to come on board to that philosophy, however, and it actually didn’t even start with Chan. It began with one of his heroes he met, flying out a window, early in his Hong Kong stuntman career: Bruce Lee.

Sam Hargrave also grew up in the era of Bruce Lee… not his actual life, but the era of his second life. Like Jesus, Lee rose again in the form of Enter the Dragon (1973), his best-known film in the west, released there just days after he had died. A cinema god promising action film salvation, suddenly the recently-departed Lee had a congregation clamouring for more sermons from the mount, and film studios obliged. They brought over his earlier films and released them in the US, re-titling them to make sense for a Western audience. 猛龍過江, actually released in 1972, became Return of the Dragon for the US in 1974. With its long, gritty showdown between Bruce Lee and Chuck Norris in the Roman Coliseum, this served as a perfect follow-up to Enter the Dragon for Western audiences, setting a new standard for what action stars, and what action in film should be.

But there were so few Bruce Lee films, and there were so many supplicants. So the 1970s saw a rise of false prophets, with names like Li and Lei and Lai and Leung, but audiences saw through them. The 1980s were spent trying to figure out how to possibly follow up Lee and create another superstar like that. In the real world too, Lee’s students were trying to figure out how to carry on his teaching philosophies and spread martial arts to an eager group of kids and young men inspired by his movies. Hong Kong studios tried to force Jackie Chan into Bruce’s mould, but his training was completely different from Bruce’s, and so were his sensibilities. While he did produce a few gems in his early kung fu films, he wouldn’t find his groove until a decade later when he transitioned to modern settings with more comedy and big stunts. Chan’s path was very different from the film vision Lee had portrayed: where violence was real, deadly, and tragic.

Back in California, Lee’s own son Brandon was training with Lee’s friend and first disciple, Dan Inosanto, who’d carried on Bruce’s teaching legacy through several martial arts schools. Brandon had an eye on going into films early on as well but was mostly acting on stage during his teens. However, his friend and another Inosanto student, Jeff Imada, had gotten work as a stuntman throughout the ’80s, and by the end of that decade had impressed enough people that he was getting to call the shots on “stunt coordinating”. You see, Hollywood still didn’t have a dedicated term for a fight choreographer. But as Imada put down some of the most iconic brawls on film, like the alley fight in They Live (1988), or the many scenes from Road House (1989) that your old college roommate would play on repeat, the industry was starting to change. Still, Imada needed someone to bring in the depth of technique he wanted, a team of people who were highly skilled and could pull off high-octane action scenes on a budget that didn’t allow weeks and weeks to rehearse. He wanted to bring in Brandon.

Brandon Lee’s early life seemed blessed with all his father’s strengths and none of the “weaknesses”. He grew up learning English alongside Cantonese, punching and kicking along with walking. His “uncles” Steve McQueen and James Coburn would drop by the house, and he grew up with Hollywood connections and more westernized, traditionally handsome features. The only problem was… he was Bruce Lee’s son.

Perhaps because of this, he was a rebellious, leather-jacket wearing, Kerouac-quoting, motorcycle-riding, street-brawling, Shakespeare-acting young bad boy. But he was also legitimate Hollywood gold, poised for a breakthrough once he got back from proving his bona fides in Hong Kong. Jeff Imada teamed up with him for his first US starring role in the film Rapid Fire (1992), a B-rate blockbuster with action scenes rivalling anything Jean-Claude Van Damme was doing, and proving that Brandon had the charisma to grow into Hollywood’s next big summer tentpole star.

Then he was shot and killed on the set of his next film, The Crow (1994).

Not only a dark, ironic, mysterious tragedy but also a setback for the current movement of Hollywood action. It was trending towards the Hong Kong style: fast, loose, doing stunts for real, with a small, highly-skilled team. But now safety became a top priority again, and even though Imada was not responsible for Brandon’s accident, his future film work didn’t push in this direction again for another decade. Instead, it would take some of his friends and training partners from Inosanto’s school to push things to the next level. Two other stuntmen named Chad Stahelski and David Leitch.

Stahelski and Leitch met through doing stuntwork that sprung out from the Inosanto schools in the 1990s. They’d both worked with Imada but were looking to make their own names, and as they followed in his footsteps, they eventually teamed up to create their own stunt team, 87Eleven. However, they’d also freelance, still working as actors themselves and appearing in separate projects in some of the best action scenes of that decade, like the original Blade (1998) and 300 (2006), or the visceral and realistic knife fighting in 2003’s The Hunted and SWAT. But it was their collaborations with the Wachowskis that really changed the game, first on The Matrix films, then on V for Vendetta (2005) and eventually into the world of superhero films. And this is where Sam Hargrave comes onboard.

From Lee in the ‘70s, Imada in the ‘80s, Leitch and Stahelski in the ‘90s, and then Hargrave in the 2000s, Hollywood was always in need of young, tough guys who could take a fall, take a beating, and still snap off a couple of kicks that look super real every single take. The stuntman’s life is a hard one though, where you often get paid per day or per stunt and have little say over what the final result looks like. Each generation had progressively gotten to share more of their own experience and ideas and techniques, but it was only in their small pet projects like Ninja Assassin (2009) that you got to see them push the action genre forward. Otherwise, you might just remark that ‘those fights were actually pretty good!’ nestled into a much bigger Brad Pitt or Hugh Jackman story (who Stahelski and Leitch had doubled for). It was the latter’s Wolverine movies that provided the lads with their entrance to the new Hollywood royalty of action films: the Marvel superhero movie.

Turning in riveting action scenes on this kind of scale in front of major Hollywood producers is what blew the lid off for 87Eleven. They came on to Captain America: The Winter Soldier (2014) with the Russo Brothers, and created some of the grittiest, most intense action scenes in any Marvel film to date. Then they went off to go re-team with their buddy Keanu (who Stahelski often doubled for) on John Wick. Hargrave had gotten connected with them by then, a younger martial artist still trying to make a go of his acting career. But he took over for Stahelski as stunt coordinator on Captain America: Civil War (2016) while Stahelski and Leitch did Second Unit directing on it. This triumvirate of ass-kicking talent coordinated throughout the next several Marvel films while they lined up their own projects. They would kick off a virtual Renaissance of the Hollywood action film industry, with pressure to have more authentic action, with less editing cheats, closeups and cutaways. More real, “old skool” HK stuff, and consequently, a more highly-skilled team that worked with the actors to help transform them far beyond the abilities that had been expected from action stars of the past.

Stahelski continued to lead this charge with John Wick: Chapter 2 (2017). Leitch got his shot to direct solo with Charlize Theron (who Stahelski had been wanting to work with again since 2005’s Æon Flux) as a Wick-meets-Bond cold war spy in the astounding actioner Atomic Blonde (2017). Hargrave did the stunt coordinating, as well as continuing to do that for all the Russo Brothers’ stuff. Then Stahelski put together John Wick: Chapter 3 (2019) while Leitch filmed Deadpool 2 (2018). Aside from audiences being fully on board, critics found themselves surprised to not be getting tired of… action film sequels? Unprecedented.

With 87Eleven films starting to dominate the action landscape so much that they were competing with themselves (Tron: Legacy and The Mechanic had been released only weeks apart for example), the question was: when was Hargrave going to direct? Stahelski was starting to move more into nurturing new talent and the business side of 87Eleven, and Leitch was getting more big bombastic action work like Hobbs & Shaw (2019), so it seemed like Hargrave was the heir apparent to make lean, mean actioners. And boy did he show his pedigree with Extraction.

The role of Tyler Rake in Extraction has finally given Chris Hemsworth that iconic character he’s been looking for outside of the realm of funny costumes and wigs. It’s a stripped-down, visceral film world that capitalizes on the decade-long fitness journey of the Aussie pretty boy which took him from soap opera star to fit-biz entrepreneur. Nowadays, Hemsworth is probably as well-known for his Instagram workout routines and his bromance with stunt double Bobby Holland as he is for any particular one of the many stabs he’s made at leading a film. Collaborations with Ron Howard, Michael Mann, and F. Gary Gray have failed to pay off, and his attempts at getting a franchise role going outside of Marvel have fumbled. But in Extraction, Sam Hargrave uses Hemsworth’s natural talents to create a character worthy of John Wick’s legacy… should the Baba Yaga ever finally go back into retirement.

Extraction in many ways seems like a culmination of many techniques that have been growing and developing since Bruce Lee first started demonstrating real martial arts on film. Lee initially had to slow his movements down so that the cameras could catch them, but the push as technology has developed has been to make action scenes faster and more intense. Lee pushed for more immersion, by just leaving the camera on the actor at mid-distance so you could see their moves. Hong Kong films ran with his lesson, though Hollywood tended to obscure action with shots that were too close and too blurry. For all the work that Jeff Imada did with Matt Damon on The Bourne Identity (2002), you can’t see any of the quality of it through Paul Greengrass’ shaky cam on the sequels. However, in films from Leitch, Stahelski, and Hargrave, they trust the actor’s execution of all the training and show that to the audience. To glorious effect.

As much as it can seem like a marketing “gimmick”, audiences have been pulled in by seeming “one takes” at least since Alfred Hitchcock hid the cuts in his film, Rope (1948). Cinephiles can get a bit over-obsessive about these and let it overshadow the film, as happened with all the advance press for Sam Mendes’ 1917 (2019). But when the “oners” help to serve the story, to pull you into a particularly gripping scene, they become far more than good press. And the level of difficulty doing that with stunts is far greater than with acting performances. That’s what makes the nearly 12-minute action scene in Extraction such a show-stopper. It’s far from the only gripping scene in the film, but it follows Hemsworth’s Rake as he drives, shoots, knifes, and brawls his way through walls, out windows and into traffic in an effort to extract the targeted son of a crimelord.

The sequence shows off many of Hemsworth’s talents, blanketed by the kind of archetypal, injured anti-hero character-building that made John Rambo, John McClane, and John Shaft tortured action heroes cut from a different cloth. Of course, you put any kid into an action movie and you can guess where the relationship is going. This is a genre film through and through and more about heightening and elevating the genre rather than upending it. The plot is fairly straightforward, the streets are fairly dusty, the physical punishment is fairly inhuman. But it has a few nice surprises, makes two hours fly by like it’s 80 minutes, and it leaves you hoping that somehow, despite all odds, Tyler Rake and his team will be back for more. Either as a prequel or an absurdist sequel in the vein of Crank: High Voltage (2009), the fact is that Hemsworth has found his new leading man role, and Hargrave has founded a worthy franchise.

Extraction 2 will be released by Netflix this year, and Hargrave and Hemsworth seem driven to exceed themselves. Soon after, Leitch will be blessing us with a new ensemble action film led by Brad Pitt as an assassin stuck on a… Bullet Train (2022). The trailer looks like “a bit o’ the ol’ ultraviolence” and dark comedy of Deadpool 2, but in Japan. Stahelski will be bringing us John Wick 4 in 2023, which adds HK legend Donnie Yen to the Wick-verse, as well as Scott Adkins (whose own podcast episodes with Stahelski and Hargrave are jam-packed with clips from their careers.) Simply put, the 87Eleven action train keeps rolling, and as long as their films keep finding an audience, we can expect that Hollywood will have to keep listening. As an action fan, I’m here for it. The HK film industry might’ve died, but the next best thing would be Lee’s students passing down his knowledge and vision, building on it and improving where they could. I have to think that if he watched Yen and Reeves in John Wick 4, he’d have a few pointers. But he’d look at how far the industry had come since Kung Fu (1972), and he’d be proud.

Written by Jeff Light