LOVE ACTUALLY: Consuming Christmas

I love Christmas. I also love films. However, I tend not to like Christmas films. There are some exceptions to this personal rule of mine. It’s a Wonderful Life (1946) is a beautiful drama, one that becomes all the more endearing with the annual re-watches. Miracle on 34th Street (1947) is another classic Christmas film that manages to charm and captivate over and over again. Meanwhile, The Nightmare Before Christmas (1993) is modern phantasmagoria on celluloid, a magnificent blend of festive cheer, adventure, and Gothic psychedelia, all captured in jaw-dropping stop-motion.

However, many Christmas films feel more like an advertisement for the holiday season, with paper thin stories that would probably not be tolerated—let alone cherished—if it weren’t for the underlying Yuletide theme. These films are easy to watch specifically because they’re so simplistic, and since the themes surrounding Christmas (love, forgiveness, kindness, community) are self-evident, no work is done to weave them into the narrative. Such ideas are simply implied by the season and we are expected to do all the legwork.

At this point, perhaps it’s worth mentioning that I’m not going to write a grouchy review of why your favourite Christmas movie is actually terrible; there are lots of films I haven’t mentioned which I think are absolutely fine. Neither will I list the Christmas movies I find to be shallow and cheap—we haven’t got all day, after all. The Hallmark Channel released over 20 Christmas films last year, which means it probably takes them less time to write those things than it took for me to write this essay.

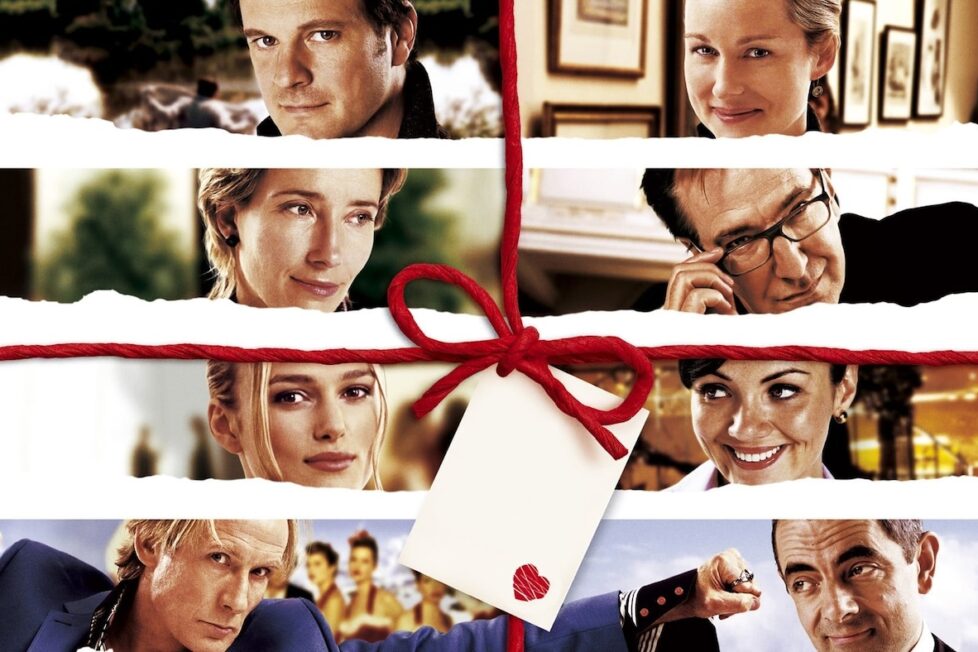

Instead of dissecting the entire genre, I’ll focus on one film in particular: Love Actually (2003). What movie captures the quintessential Christmas spirit more potently than Richard Curtis’ holiday-themed romance? I don’t necessarily dislike the film and I understand its appeal. In fact, my main criticism lies in the fact that it’s designed to be liked. With its charismatic cast, fan-favourite soundtrack, Love Actually is manufactured to give you that warm and fuzzy Christmas feeling. However, this sensation was created in a lab.

My argument is a teleological one: the film is rather obviously just another object of Christmas consumption, designed to be easily digested by the largest number of people possible, thus becoming another product in a season increasingly dominated by capitalist pursuits. With nine plot lines, a sensation of excess permeates this film. There’s so much love, so much romance, so much Christmas! Without sounding like the Grinch or Ebenezer Scrooge, this unrestrained surfeit can be seen as a metaphor for seasonal splurging. Noel Carroll wrote that consumerism “is a perpetual motion machine—always churning, always expanding.” In large part, that describes Love Actually.

First and foremost, let’s take a look at the stories that populate the film. There are nine stories, though Curtis originally wanted to cram in a monstrous fourteen stories of mind-numbing, incessant love and loss. It’s 21st-century attention deficit incarnate. Unlike Jim Jarmusch’s anthology films Night on Earth (1991) or Coffee and Cigarettes (2003), there is no patience, nor musing on existential questions in Love Actually. Instead, we’re whisked away to the next vignette so the entire piece never features a dull moment.

This is often used as means of praise. However, I find this sensation of constant, ceaseless stimulation to be overwhelming. Love Actually is a bit like when you’ve eaten too much Christmas cake: no matter how sweet it is, you probably feel a little sick afterwards. And Love Actually isn’t just sweet—it’s overtly saccharine. Each story features ecstasy or tragedy in various forms, but the defining principle is that they all must be extreme emotions. On top of that, all who experience their own personal nadirs in life get a happy ending; in this life, there’s no bitter pill to swallow. Nuance be damned—it’s Christmas!

This sensation of being rushed off to the next story, the next meet-cute, the next thing to be seen or had, is emblematic of the frenetic compulsivity that consumerism instils in us. Noel Carroll also wrote, “As soon as one desire is satisfied, another one is instilled.” Similarly, as soon as one plot line reaches a dramatic low-point, another exciting development is taking place in the next story. Narrative thrust is achieved by stuffing in the highlights of any and every romantic arc, picking up and dropping off in the most expedient moments.

This is true of all the characters in Love Actually, all of whom desperately pursue their desires—no matter how bizarre or unscrupulous—and perhaps even convince us we should be doing the same. Grand romantic gestures are demonstrated to be chivalrous and honourable, not harmful (like flirting with your best friend’s wife) or myopic (such as starting a trade war with the United States).

Love Actually becomes a modern odyssey of love. But much like Homer’s epic tale, it’s a myth, no matter how hard it masquerades as truth. The film spouts impenetrable platitudes ceaselessly, ensuring you’d have to be a real grump to point out how simplistic a worldview it’s suggesting. However, since I’m already here: there’s an argument to be made that such facile depictions of life, relationships, and the world at large can have an insidious effect. It can make people adverse to nuance. Political philosophers have long since made the argument that consumerism abates a person’s desire to engage in democracy. Unlike Christmas shopping and Love Actually, civic discourse is slow, laboursome, and brimming with complexity.

A romantic comedy doesn’t have to fit any of these descriptions, but ideally it could be realistic, particularly considering Hugh Grant’s voiceover assures us that everything depicted is true to life. However, much like a lobster in the nativity play or Colin’s erotic voyage to America—which plays like a very bad porno, albeit it seemingly does this intentionally—things don’t necessarily need to make sense so long as they’re fun. This is something that I would argue has become more prevalent in cinema in recent years. With Jurassic World (2015) featuring velociraptors running alongside motorbikes, and with Furious 7 (2015) showcasing a car jumping through The Etihad Towers (not once, but twice), it seems as though this is a phenomenon in franchises which is getting worse, not better.

Of course, Love Actually isn’t the sole perpetrator of this, nor is it the first. However, when we decide that a story doesn’t need to make sense or be coherent, we tacitly agree that the parameters for judging the work have been altered: it’s mere entertainment. Any criticism levelled at conflicting messages, nonsensical bromides, or problematic depictions of women is to miss the point entirely. Much like Christmas, things happen in the film that are only designed to maximise pleasure. If we’re to continue mining food analogies, Love Actually is similar to fast food in that, even if you know it isn’t good, you don’t quite care—it is what it is and you deserve a treat.

I want to clarify that there’s nothing wrong with seeking a little escapism. We do all deserve a treat every once and a while. However, stating that we require films like Love Actually to facilitate that would be conflating need with desire, which is a misunderstanding that consumerism actively encourages. Robert G. Dunn made the argument that consumer society merges need, want, and desire into an amalgam of impulsive actions and compulsive spending or consumption, becoming a “whole complex of subjective feelings and meanings surrounding the commodity.”

Love Actually is exactly this: a commodity that attempts to tackle one of the biggest abstractions in human culture—namely, love—with a vague, diffuse approach. The film meanders at breakneck speed, without reaching any definitive conclusions on the concept, though it may have convinced you it did. Curtis wanted to explore what love means, but instead, the finished product is simply lots of stories about romance, flung together with a catchy soundtrack. It’s less of a treatise and more of a treat. The film inspires an emotional response without having any genuine foundation and the story is propelled more by raw emotion than rationality, introspection, or good taste.

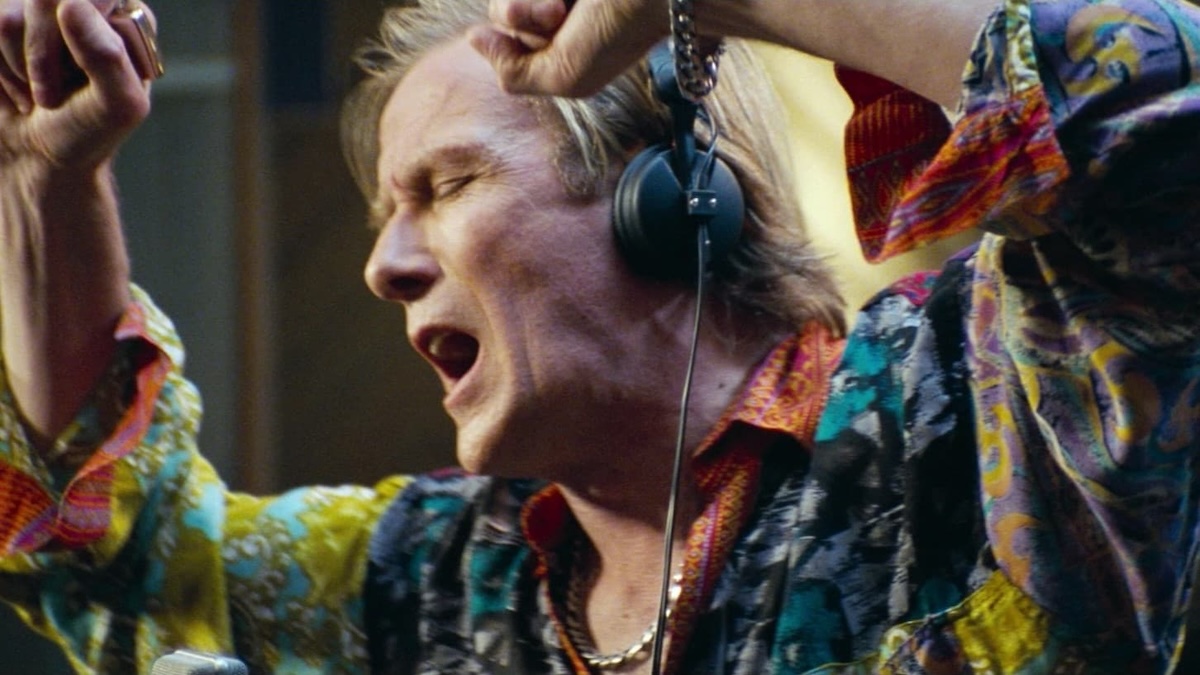

At the beginning of the film, Billy Mack (Bill Nighy), an aged rock-star, turns to his manager as they’re revamping a song into a Christmas hit, saying “This is shit, isn’t it?” Joe replies, with glee, “Yep! Solid gold shit, maestro!” This very well may have been the conversation that Curtis had with producers financing the motion picture. The film isn’t good, but after grossing a quarter of a billion dollars, it shows that Christmas sells: originally, the stories weren’t even to take place during the holiday season. Now, it’s one of the most popular Christmas films of all time. Still, for my money, I’ll take It’s a Wonderful Life.