HENRY: PORTRAIT OF A SERIAL KILLER (1986)

Arriving in Chicago, Henry moves in with ex-con acquaintance Otis and starts schooling him in the ways of the serial killer.

Arriving in Chicago, Henry moves in with ex-con acquaintance Otis and starts schooling him in the ways of the serial killer.

John McNaughton started as a delivery many for a business renting video equipment, who was then hired by his bosses, brothers Malik B. Ali and Waleed B. Ali. to direct a documentary about arms dealing. His resulting low-budget film, Dealers in Death (1984), was received well by critics, so the Ali’s asked McNaughton to make another film about the 1950s Chicago wrestling scene. A modest budget of $110,00 was agreed, but after the owner of a collection of vintage wrestling tapes doubled his asking price, the project was cancelled and the money instead used to make a horror film…

The 1980s was a boom time for horror, helped by the new home video market making films more accessible and catering for more niche tastes, so McNaughton decided to make a fictionalised version of real-life serial killer Henry Lee Lucas’s life after seeing an episode of the newsmagazine 20/20 on his conviction in 1983 of murdering his own mother and others. The Ali brothers duly hired Steven A. Jones to help McNaughton write a screenplay for Henry: Portrait of a Serial Killer, and the movie went into a fast 28-day production in 1985. It was shot on 16mm and because of the small budget most of the cast were friends, family, crew, or even strangers captured on camera during scenes. Locations, clothes, and vehicles all belonged to people involved with the production.

Henry: Portrait of a Serial Killer tells the story of the eponymous Henry (Michael Rooker), a vermin exterminator and drifter who currently lives with his deadbeat friend Otis (Tom Towles) in a gloomy apartment, where they mostly pass the time watching trash TV. Although we soon realise Henry has other pursuits, which involve murdering random people in intentionally different ways so the police can’t see a pattern to his killings. Then, Otis invites his sister Becky (Tracy Arnold) to stay with them, who starts to question Henry’s back story—including the murder of his own mother when he was a young boy, which landed him in jail—and this unusual trio coexist under the same roof.

This film marked the debut of Michael Rooker, who’s today best known for his early role in The Walking Dead series or as Yondu on the Guardians of the Galaxy movies (director James Gunn being a frequent collaborator). Rooker took the part of Henry incredibly seriously and stayed in character throughout the month-long shoot and didn’t socialise with anyone off set. Rooker’s wife didn’t even tell him she was pregnant until filming was over, presumably because she didn’t want the happy news to disrupt his mindset as Henry.

McNaughton tried to drum up interest in his film by sending tapes to critics, as they could only afford video distribution, although Henry premiered at the Chicago International Film Festival in 1986. Its ongoing success on the festival circuit led to positive reviews from notable critics, including Roger Ebert in 1989, but the MPAA gave it an X certificate rating and so a potential nationwide theatrical release with Atlantic Entertainment Group was nixed. The debate over its release did help usher in the NC-17 rating in the US, for non-pornographic adults-only films, and Henry eventually got a wide release in 1990, four years after its premiere. The UK censors, the BBFC, are notoriously stricter than their US counterparts, the MPAA, as the “video nasties” furore saw many titles banned for decades in the UK, and so Henry wasn’t available in fully uncut here until 2003.

Decades later, Henry: Portrait of a Serial Killer still maintains a scabrous reputation, but there are certainly more transgressive and sickening examples of the horror genre. I wouldn’t say it’s become tame, but it unsettles more through its tone and mood than anything we see (although a few shots are certainly memorable for their almost casual gruesomeness, such as when Henry calmly severs a man’s head in a bath tub). The low budget certainly helps the movie in that regard, as the filming techniques and acting style give Henry a pseudo-documentary feel. It’s like we’re somehow snooping on these characters and catching their depraved acts on film.

It’s easy to see why Henry stood out from the pack in the ’80s, as the era was dominated by horror that was more crowd pleasing in nature—particularly thanks to the prominence and cult appeal of slasher franchises like Halloween (1978), Friday the 13th (1980), and A Nightmare on Elm Street (1984). Ones that treated the subject of serial killers with the utmost seriousness were rarer, but often better produced and elevated by artistic filmmaking and fancier cinematography. Michael Mann’s Manhunter (1986) springs to mind. Henry is more of a throwback to the grimier days of the 1970s, with horror films like The Texas Chain Saw Massacre (1974) and The Driller Killer (1979) also having similar vérité filming styles.

This is certainly a film that will be an acquired taste, as even those who find entertainment in serial killer stories may have to recalibrate themselves to Henry’s particular pace and mood. It only has an 83-minutes runtime, but feels twice that because not a lot actually happens. We’re simply put in the company of a psychopath going about his daily life, a loser he takes into his confidence (and turns just as monstrous), and the sweet unassuming woman who’s living with them both. The tension comes from not knowing how this dynamic is going to develop, or if it might explode. Will Henry be caught thanks to Becky realising the company her brother’s keeping? Or might Henry create a worse monster in Otis who comes after him instead? There are a lot of directions the story could have gone in, and the one it chooses is thankfully the least predictable.

It’s easy to say there’s not really a lot going on in Henry and its ability to shock has waned over the years, if you’re coming to this fresh, but I did find some intrigue in how the characters of Henry and (particularly) Otis eventually come to film themselves committing crimes using a camcorder and then relive the experience from the sanctuary of their sofa on television. Otis starts the film being a typical couch potato, and doesn’t develop much more than becoming the star of his own show. Knowing what was going on in the ’80s culturally, with people worried that VHS horror would pervert the minds of the young and impressionable, it’s darkly amusing that in Henry it’s just a means to catalogue experiences. A new form of the psychopath’s sketch drawings, or a Polaroid in a tin case hidden under a floorboard.

The way we’re shown these characters also brings to mind them being animals for study, as none of them are particularly good examples of humanity, and yet this is perhaps what a human being is without education, social interaction, moral teaching, and other things that civilise us as children. Henry’s frightening because he resembles a caveman thrown into the late-20th-century; illiterate, incurious, aimless, and only really killing people because it’s something to do and feels like a reasonable response to difficult people who are in his way. He can dispose of a body and they’re gone. It makes him feel better to permanently end their lives. He’s only motivated by awareness his behaviour isn’t normal for most people, so he doesn’t want to get caught (the one lesson from adolescence after killing his own mother), but he’s otherwise operating on pure primal instinct. And it’s chilling to reckon with that idea, in contrast to other portrayals of serial killers on film that are more often tortured geniuses or motivated by things we can sympathise with on some level. The only vaguely redeeming feature of Henry is that he seems to find incest abhorrent, but then rescuing someone from that ordeal doesn’t mean he has their continuing safety foremost in mind.

USA | 1986 | 83 MINUTES | 1.37:1 | COLOUR | ENGLISH

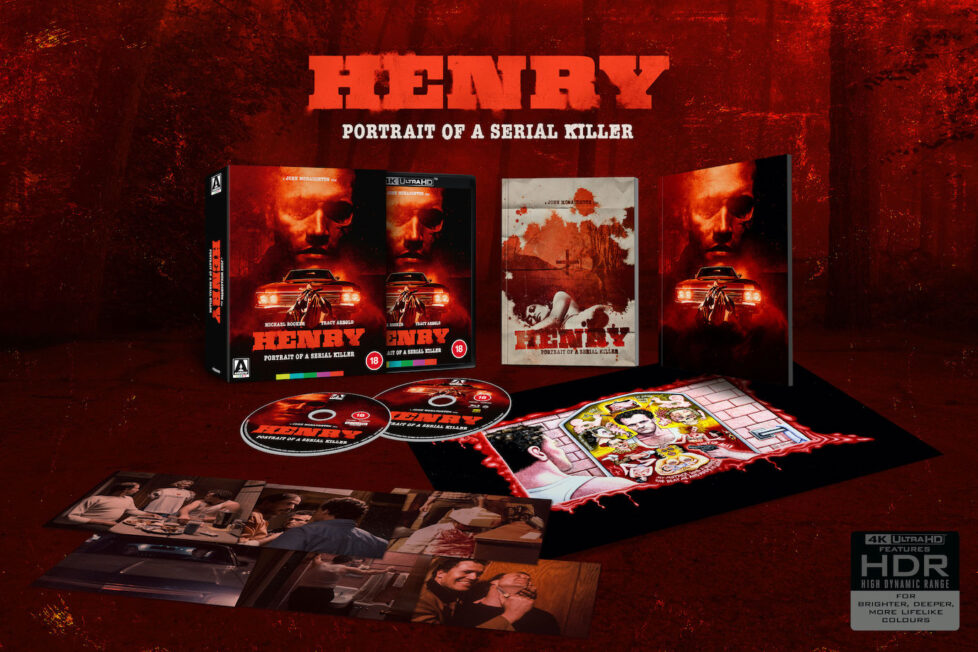

Henry: Portrait of a Serial Killer isn’t a film I saw back when it was first released, so I have no recollection of the image quality being presented on VHS or DVD, but I’m sure those who only saw it that way will be bowled over by Arrow Video’s 4K restoration here. I’m sure many British horror fans saw it on a bootleg tape, in its uncut form, so the disparity will be even more pronounced. But this is still a cheap 16mm film shot decades ago, so don’t expect miracles! The ‘pillar boxed’ 1.37:1 ratio image is grainy and often noisy, which suits the tone of the film and reflects how it was made, but if you’re expecting a pin-sharp 4K resolution and HDR10 that stand out… prepare for disappointment. This is merely the best a grubby-looking film from ’86 has looked on home video.

The 5.1 DTS-HD Master Audio mix is primarily focused on the front channels, so in many ways you’re better off sticking to the original 2.0 stereo mix. However, switching between the two, there’s a touch more impact to the 5.1 DTS version, which I grew to favour even if the stereo mix offers perhaps slightly more clarity with the dialogue because there’s little else getting in the way of that.

director: John McNaughton.

writers: Richard Fire & John McNaughton.

starring: Michael Rooker, Tom Towles & Tracy Arnold.