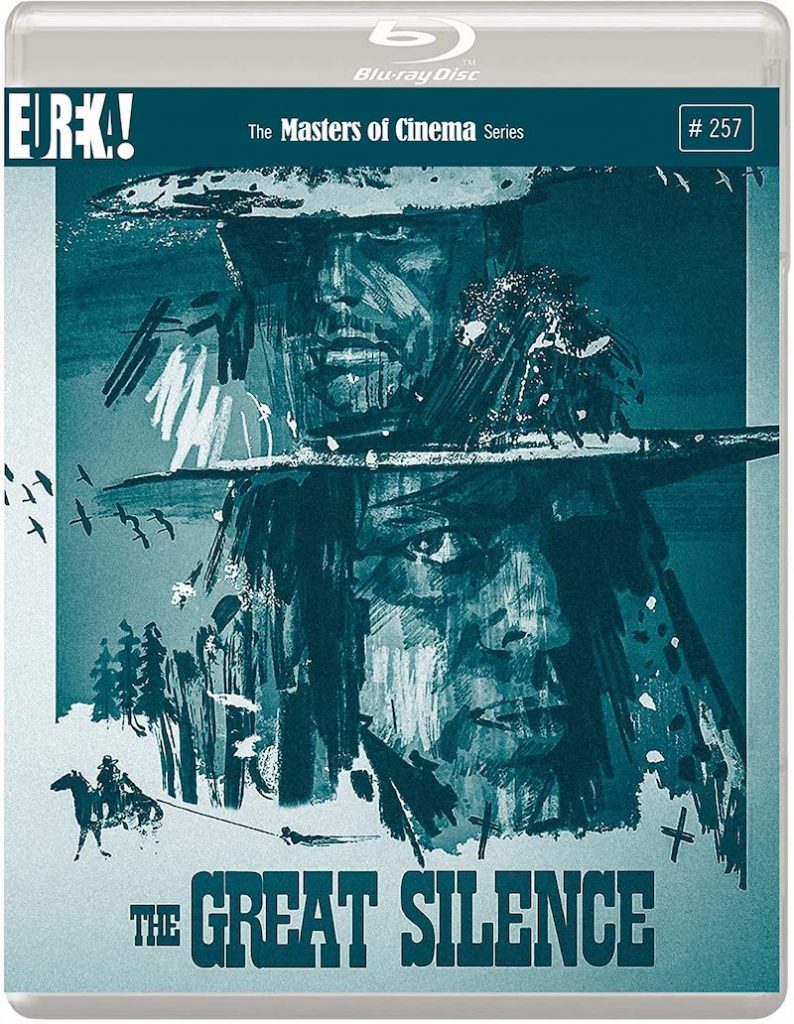

THE GREAT SILENCE (1968)

A mute gunfighter defends a young widow and a group of outlaws against a gang of bounty killers in the winter of 1898...

A mute gunfighter defends a young widow and a group of outlaws against a gang of bounty killers in the winter of 1898...

If The Great Silence / Il Grande Silzenzio could be summed up in a single word, that word would be… bleak. I wouldn’t be the first to say so, either! Considered by many to be amongst the greatest Spaghetti Westerns ever made, writer-director Sergio Corbucci’s dark opus is certainly a stand-out, if not unique, example of the genre. When I say ‘dark’, though, I don’t mean visually; immediately, the glaring starkness of its snowbound setting marks it aside from the typical dusty desert backdrop one expects from the genre. However, its central strength lies in ticking nearly all the other Spaghetti Western tropes, whilst becoming increasingly unpredictable and building toward a shockingly uncompromising finale.

I would only recommend this film to people who are in an emotionally robust mood, but for western aficionados it’s required viewing. This beautiful, limited edition 2K restoration on Blu-ray from Eureka Entertainment is a welcome addition to their ever-growing ‘Masters of Cinema’ imprint, presented with no less than three full-length audio commentaries, some nice extras, and a worthwhile collector’s booklet.

Like most jobbing directors working in the genre-driven Italian ‘filone’ film industry, Corbucci had made a few ‘peplum’ sword-and-sandal adventures, before jumping on the western bandwagon set in motion by Sergio Leone’s A Fistful of Dollars (1964). The Great Silence was Corbucci’s seventh western in just four years and the middle part of his so-called ‘Mud and Blood’ trilogy, beginning with Django (1966) and concluding with The Specialists (1969). Apart from their blunt brutality, these three Euro-western classics are only linked by style and common themes including political undertones.

The Great Silence screenplay started life as a sequel to Django, which had performed exceptionally well at the domestic box-office, but things changed when Franco Nero turned down the opportunity to reprise his lead role. By then, pre-production was underway as an Italian-French co-production and the French producer, Robert Dorfmann, brought the replacement lead onboard. Jean-Louis Trintignant had attracted international attention starring opposite Brigitte Bardot in And God Created Woman (1956), and then as the male lead opposite Anouk Aimée in A Man and a Woman (1966)—which, at the time, was the most internationally successful French film ever. As a result, he’d earned a reputation for romantic leads in somewhat intellectual films and was ready to expand his repertoire. Foreign markets were always the safest bet when doing this because, if the movie flopped, it wouldn’t seriously register on the international radar and cause major career damage, but a success could only help one’s export potential.

Corbucci now felt he needn’t pick up any narrative continuity from Django and, with a French-speaking actor in the lead, he revisited an old idea he’d had for a mute gunslinger that would take the strong, silent hero archetype to a new level. Reputedly, he was also saddened by the recent, high-profile deaths of good men who stood up for the oppressed and spoke truth to power only to be abruptly silenced: President Kennedy had been assassinated in 1963, Malcom X was murdered in 1965, Che Guevara was executed in 1967, and both Martin Luther King and Robert Kennedy were assassinated in 1968. Corbucci wanted to reflect these tragedies and remind audiences that good can defeat the wicked, but only for a short time before being crushed by those in power and the incremental rise toward freedom is painfully slow and beset with many tragedies.

Another idea he’d been toying with was a western set in a barren, snow-bound location that would resonate with the bleak premise. Apparently, this had been intended for Django but budgetary constraints forced him to compromise with an excess of mud instead. However, with that film’s surprise success, he found he had sufficient funds this time round for some location filming. Plus, staying at a famous ski resort whilst filming in the Italian Dolomites became an extra incentive for the cast when negotiating their contracts.

The opening scenes are suitably striking, capitalising on the graphic opportunities of the brightly blank terrain. A distant, isolated figure on horseback appears near the top of the paper-white frame slowly approaching the camera, which jerks a little disconcertingly to track their approach as they leave a trail in the snow behind them. Abruptly, fragments of faces are revealed in close-up, part obscured by the snowbanks they hide behind and we realise we’re seeing through the eyes of one of these men who lie in wait to ambush the traveller. We then get an extreme close-up of the horseman when he’s alerted to the trap by a flurry of crows taking flight, like black rags against the white. The confrontation is over quickly and only one of the would-be waylayers is left standing, but only long enough for some essential exposition. As he pleads for his life, we learn that the man on horseback is known as Silencio (Jean-Louis Trintignant) and the others had been bounty hunters. Instead of killing the man, Silencio shoots off his thumbs to guarantee he’ll never be able to use a gun again.

As Silencio turns to continue his journey into the wilderness, the bounty hunter fumbles his pistol in bloody hands but is felled by the shot from an unseen gun. A gang of peasants reveal themselves and explain that they are no friends to the bounty hunters either, as they too have a price on the heads, simply for trying to survive in desperate times. This opening scene sets out one of the central themes of money being a tool to influence laws that can, in turn, be used to oppress and conquer the American West.

There’s no way The Great Silence could’ve been made in 1960s America! It may be pure fiction and yet it’s based on a mash-up of different dark periods in US history, of which there are admittedly plenty to pick from. It proports to be based on events leading up to the Snow Hill Massacre of 1898, for which I could find no direct reference. However, that same year saw the terrible events of the Wilmington Massacre in which a white supremacist American militia lead a coup destroying swathes of the city and murdering more than 60 people in one day. Those victims were black Americans, but in The Great Silence it’s ambiguous who the oppressed are, except its clear they live on land that has become valued by wealthy incomers and are therefore ‘in the way of profitable progress’.

Despite warnings not to, one of the young outlaws, Miguel (Jacques Dorfmann) decides to go home to his mother (Pupita Lea Scuderoni) for respite from the blizzards, and it’s there that bounty hunters Charlie (Bruno Corazzari) and the coldly efficient Tigrero (Klaus Kinski) find and dispatch him. Around this time, the versatile Kinski was almost ubiquitous in euro-westerns. He made more than 20 of them following his appearance in For a Few Dollars More (1964), with The Great Silence giving him one of the few starring roles in the genre, along with his memorable protagonist in And God Said to Cain (1970)…

Here, he’s a cold-blooded killer who, while clearly the villain of the piece, is actually operating within the legal parameters of the day. Technically, he’s in the right when he guns down his victims and, as he will point out, is acting on behalf of the authorities who place the bounties with the proviso to bring them in dead or alive. Alive is more expensive, so he always opts for the easier method.

It’s a great, underplayed performance in which his self-righteous smugness becomes increasingly infuriating, keeping a tally in his little accountant’s notepad. To him, life and money are interchangeable currencies. It’s just business and he’s already convinced himself he’s helping to make the world safer for decent white folk by clearing out the “perverse and godless criminals.” After one kill, he jovially comments “what a world we live in! A negro worth more than a white man.”

That so-called outlaw, Middleton, had a bounty placed on his head by the local governor and justice of the peace, Henry Pollicut (Luigi Pistilli), who lusted after the mans’ young wife, Pauline (Vonetta McGee), and wanted to force the sale of their homestead. Pollicut, who we later learn is entwined with Silencio’s lifelong quest for vengeance, hoped that the penniless widow would then be indebted to him for his financial support and need somewhere to live. Pistilli is another euro-western regular who’d also appeared with Kinski in For a few Dollars More. By now, though, news has reached the town of Snow Hill that the Silencio is coming and both Miguel’s mother and Middleton’s wife both send word that they want to hire him to exact vengeance on their behalf.

Caught in the middle of the powerplay between Pollicut, Tigrero, and Silencio is the newly appointed Sheriff of Snow Hill (Frank Wolff) who arrives on the same stagecoach as Silencio. Y’see, both men have lost their horses, on the way, Silencio’s to the bitter cold and the Sheriff’s to the band of outlaws who stole it for food because to them it’s just as good as beefsteak. Being a mute, the conversation is definitely one-sided and this is a device Corbucci exploits throughout, leading to characters feeling the need to deliver monologues and tell all to fill that silence. This also reinforces the old adage that actions speak louder than words. For the most part, Silencio’s enigmatic and stoically still, but when he does move, his actions for better or worse are decisive.

The dialogue remains sparse throughout, though combines into a balanced and eloquent indictment of the American way, or any such money-driven power structure for that matter. The characters make judgements of each other according to perceived gradients of power and authority. Some lives are worth more than others, some people are more or less godly than others. There are three sheriffs involved at different points—one wears a badge, but is an imposter, one is simply corrupt, but the new Sheriff intends to uphold the law, not realising that he’s really just as much the puppet of a corrupt system.

Ennio Morricone’s stand-out music underpins the emotional depth throughout and really does half of the actors’ jobs for them. Having said that, the cast is strong all round, though I suspect that the harsh conditions of filming in the snowbound Dolomites partly contributed to the convincing performances. One feels chilled just watching and the cinematography of Silvano Ippoliti, capitalises on the contrast between the cold blue-whiteness of the exteriors and the warm, almost orange, lighting of interiors. The beautiful Eastman colour process also enhances his subtler, some might say murky, colour palette.

The film was shot mainly on location using purpose-built sets in the mountains of northern Italy and at the western town backlot at Elios Studios, which will be familiar to some viewers from so many Italian westerns. Corbucci manages transitions between location and studio-based shots seamlessly with brilliantly matched lighting and visual grading. In one scene, Frank Wolff walks down a street at Elios and rounds a corner in the perfectly matched mountain location.

Apparently, the snow and sub-zero temperatures presented many technical problems, interfering with camera operation and film speeds whilst making it impossible to use dollies. So, Corbucci opted to use small Arriflex cameras, sometimes shooting from horseback to add a dynamic urgency to many sequences, as well as filming from the backs of trucks or resorting to hand-held. The weather conditions fluctuated rapidly so gauze filters were placed over the lenses to protect them from sudden snow flurries, reduce troublesome snow-glare, and lend a foggy softness that would help cover the joins. In some of the opening shots, these gausses have left a mesh-patterned artefact which is now rather more obvious in HD than it would’ve been on release!

The Great Silence performed moderately in Italy but faired better at the box offices of France and Germany where its two stars, Trintignant, and Kinski, had respective traction. The extreme ending ensured that no US distributors were brave enough to take it on and realising this, Corbucci filmed a more up-beat ‘fairytale’ ending that just highlights how fitting the harder-hitting version is.

International distribution was potentially bagged by 20th Century Fox. However, Darryl F. Zanuck hated the film with a vengeance and shelved it, suggesting using the rights to make a version fit for the US market. This project is believed to have resulted in Joe Kidd (1972) the wintery western in which Clint Eastwood totes the same distinctive Mauser repeating pistol used by Silencio… but the similarities end there. So, The Great Silence sank into relative obscurity until championed by Alex Cox who screened it in 1990 as an episode of his Moviedrome series. Since then, interest in this unusual spaghetti western has grown until it warranted this 2K restoration in 2017 followed by a limited theatrical release. It has since undergone another digital restoration and preservation at 4K and is now widely recognised as one of the most important Italian westerns… it doesn’t have to be fun to be entertaining!

ITALY • FRANCE | 1968 | 105 MINUTES | COLOUR | ITALIAN

director: Sergio Corbucci.

writers: Vittoriano Petrilli, Mario Amendola, Bruno Corbucci & Sergio Corbucci (story by Sergio Corbucci).

starring: Jean Louis Trintignant, Klaus Kinski, Frank Wolff, Luigi Pistilli, Mario Brega, Marisa Merlini & Vonetta McGee.