Vengeance Trails: 4 Classic Westerns (1966-1970)

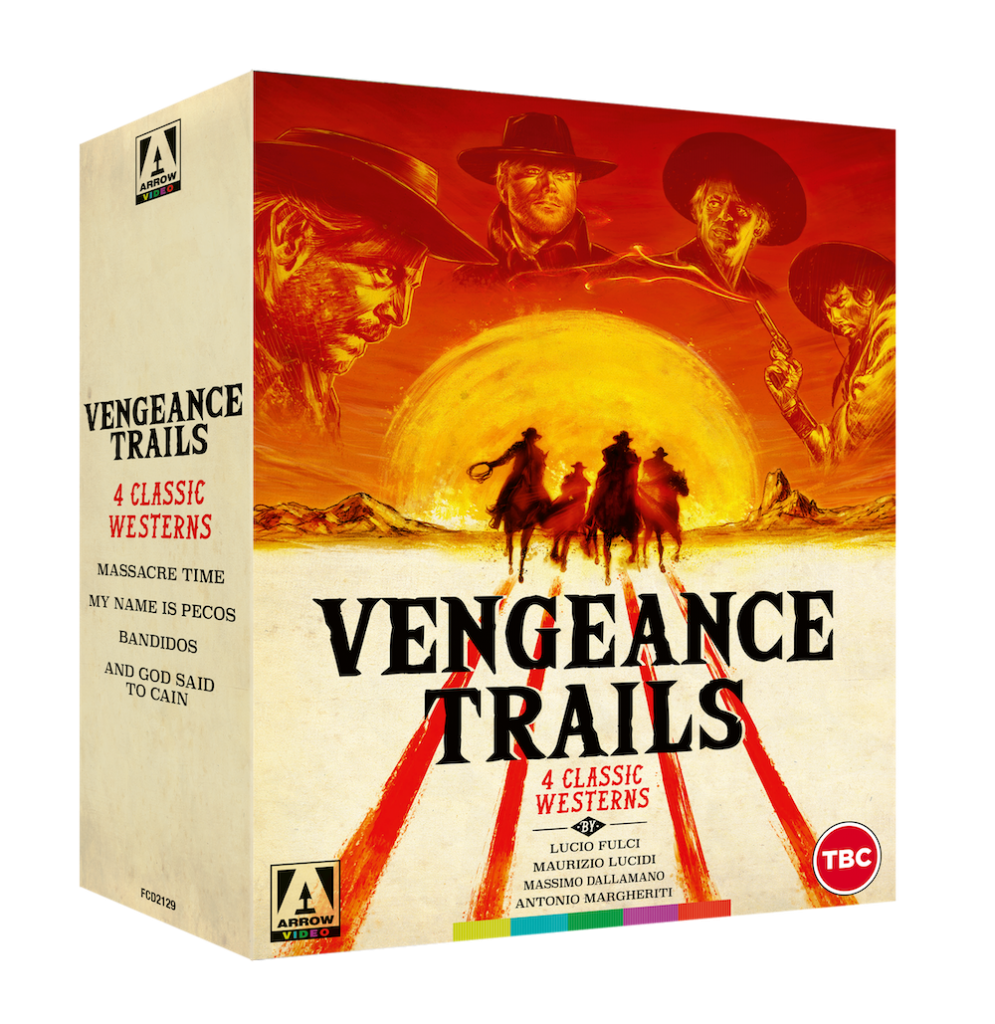

Vengeance Trails is a handsome new box-set of classic European westerns from Arrow Video. The four films, nicely packaged on separate Blu-ray discs, each with individual artwork and its own informative extras, are lesser-known variations on a theme and remain exceptional examples of the genre from a set of solid pulp directors just as readily associated with other types of films.

Horror maestro Lucio Fulci gives us the stylish and super-violent Massacre Time, with Franco Nero and George Hilton sharing the lead; pulp and peplum specialist Maurizio Lucidi delivers a very satisfying by-the-numbers ‘spaghetti western’ with My Name is Pecos, starring Robert Wood; Bandidos is a classic that should be seen by any western aficionado, directed by accomplished cinematographer Massimo Dallamano; and Antonio Margheriti, better known for his cannibal-themed video nasties, rounds things off with And God Said to Cain…, a precisely paced Gothic western starring cult actor Klaus Kinski.

All four films presented here were made at a time when the Italian movie industry seemed unstoppable. Filone, or genre-driven Italian ‘pulp’ cinema, fuelled most of the domestic output with around 30 westerns a year coming out of the Italian studio system from the mid-1960s to mid-’70s—mostly co-funded with Spain and with a suitably international cast and crew. The term ‘filone’ is thought to have originated from the name of a type of ‘everyday’ bread popular in Italy, so it’s like saying the studios made their ‘bread-and-butter’ with a certain type of film.

In the 1950s, the primary filone had been the ‘peplum’, a historical ‘sword-and-sandal’ epics inspired by Old Testament tales and Greek myths. They proved immensely popular and were the keystone of domestic Italian cinema. The first filone to find international appeal were Italian westerns that hijacked the tired iconography of the Wild West and presented a significant challenge to Hollywood’s dominance of the genre.

And because they weren’t made by Americans, the ‘spaghetti westerns’ weren’t obsessed with revising and romanticising the history of the pioneers and settlers. Instead, they exploited the setting as a backdrop for mythic stories that also revitalised the cinematic landscape and language of the western. In the mid-’60s, Sergio Leone and Sergio Corbucci are cited as the two breakthrough directors at the vanguard, but for the ensuing decade pretty much any jobbing director working in Italy would’ve made a western or two. As would be expected, the majority are predictable pastiche but, among the 600 or so titles, there are some classics that still ‘ride tall in the saddle’, and four of those are showcased here.

A prospector and his drunkard half-brother must fight a rancher and his sadistic son after they seize control of his farm.

This is probably the closest in the box-set to what one might expect from limited exposure to just Leone’s Dollars trilogy, which shouldn’t be surprising as the writer here, Fernando Di Leo, also had a hand in scripting A Fistful of Dollars (1964) and For a Few Dollars More (1965), as well as another equally seminal Euro-western, A Pistol for Ringo (1965) along with its sequel Return of Ringo (1965). Although Massacre Time is Di Leo’s first solo credit, he was given uncredited help by Fulci, as one might expect, and also repeat collaborator Enzo Dell’Aquila. But for all the team’s creative credentials, the story doesn’t really make sense and ends up being needlessly convoluted for such a simple plot, but that’s not to say it isn’t a satisfying viewing experience.

Massacre Time still works well, but only because of the fortuitous meeting of two of the genre’s top stars, Franco Nero and George Hilton, with a superb visual stylist in Lucio Fulci. This was the director’s first of three ventures into the western territory. He’s better known as a director of some memorable 1970s gialli, such as Lizard in a Woman’s Skin (1971) and Don’t Torture a Duckling (1972), and would later establish himself as one of Italy’s important horror auteurs with the notorious Zombie Flesh Eaters (1979) and its follow-up ‘Gates of Hell’ trilogy, beginning with City of the Living Dead (1980), a set of films that helped define the ‘video nasty’ in the early-1980s.

Considering this was one among hundreds of pulp films being churned out by the Italian film industry, and Fulci was hired as a ‘jobbing director’, it’s way better than it had any right to be. There’s plenty of visual pleasure to be found and Fulci ensures that every shot counts—both ballistically and photographically! He’s helped here by veteran cinematographer Riccardo Pallottini, who’d already shot around 50 films in 15 years (see what I mean about churning ’em out?) and it won’t be the only time you read his name today…

Franco Nero was fresh from playing the lead in Sergio Corbucci’s Django (1966), which was to be a surprise international hit and spawn a series of sequels. In some territories, Massacre Time was promoted as the first of these. But although his character, Tom Corbett, looks similar with a sheepskin jerkin, black hat, and riding cape, they have little else in common. However, the film does its best to live up to the ultraviolent template set down by Django. In fact, the Spanish investors pulled out during preproduction because of the script’s amoral attitude to violence, forcing Fulci to seek alternative locations in Italy. Although this meant a significant reduction in budget, it seemed to work in his favour and the less familiar locations help to give Massacre Time its distinctive look, another thing that sets it aside from many of its contemporaries.

Tom Corbett (Franco Nero) is prospecting for gold when he receives an enigmatic note asking him to return home with haste. It seems he’s been away for a while and things have really changed, as he finds his family’s old homestead run down and occupied by strangers. The tyrannical Scott family now uses fear and random violence to rule the town he grew up in. His brother, Jeff ‘Slim’ Corbett (George Hilton), is now an alcoholic outcast living in an adobe shack, still cared for by their old nanny, Mercedes (Rina Franchetti), and she’s the only person who seems happy to see Tom again.

He’s keen to uncover the truth about what’s happened in his absence, but nobody, not even his brother, will tell him who the Scotts are or even where to find them. The best source of information turns out to be the old Chinese undertaker (Tchang Yu) who questions the wisdom of Confucius a lot and plays piano in the saloon. Yes, several cliches for the price of one! But even he fears telling Tom too much and doesn’t want to spoil the story too early.

Tom decides to visit Carradine (John Bartha) who sent the summoning note and finds him just saying grace with his wife and two children. He takes Tom out to the barn to talk but Carradine is shot by an unseen gunman before he has the chance to explain anything except to mention the Scotts. Tom rushes back to the house to find the entire Carradine family executed at the dining table. We now realise that Massacre Time, as well as entertaining us with cliches, also has a dark and uncompromising side. Suppose we should’ve guessed that from the title!

This oscillation between light and dark is a notable feature of the film which is all about different types of conflict. The two protagonists embody opposites, with Jeff laughing at nearly everything and constantly swigging from his ever-present flask of tequila, whilst Tom remains sober and stoic throughout. Together, they may just manage the semblance of a complete, balanced person. They’re so different that one wouldn’t guess they were siblings, and therein lies the crux of the confusion…

Clearly, the Carradines knew secrets about the Scotts that someone desperately wanted to be kept from Tom. What baffles him is that he’d been just as easy to kill out at the barn but had been spared for some reason. He’s a quick draw, sure, but he also seems to get out several life-threatening situations with miraculous ease, as if Scott’s henchmen are trying to keep him alive. It’s hard to understand why his brother, Jeff seems so keen to see the back of Tom and refuses to explain anything either, but maybe the tequila has affected his memory?

There’s also a generational conflict between old man Scott (Giuseppe Addobbati, credited as John M. Douglas) and his sadistic, clearly unbalanced son, Jason (Nino Castelnuovo), who enjoys playing the organ, crushing rose blossoms, and creepily caressing his father. That’s when he’s not gunning people down at the merest provocation or bull-whipping Tom to within an inch of his life in a grueling sequence that marks the symbolic death and resurrection of our hero.

I watched Massacre Time twice—once in the dubbed international version, which I strongly advise against as it makes the performances come across terribly, and once in the Italian with subtitles, in which Hilton, Nero, and Castelnuovo are infinitely more convincing. However, I’m sure much of the dialogue had been changed, and maybe even the explanation of who’s related to who was different! Or perhaps it’s just too confusing to keep track of but, without spoiling things too much, the big secret at the heart of the narrative is to do with whose father killed whose father, and out of the several candidates who are actually blood relatives and who are simply spiritual siblings.

Confused? You will be… but by then, you really won’t care because you’ll know who the very, very bad guys are and will just be waiting for the titular massacre when they’re sure to get their just deserts. Which, rest assured, they do, in a suitably ludicrous all-action shoot out of two against the many. What more could one want for from a euro western?

Le Colt Cantarono la Morte e fu… Tempo di Massacro was given a summer release in 1966 but the international, dubbed and trimmed version wasn’t distributed until 1968 when it was picked up by American International and retitled The Brute and the Beast to associate it with The Good, the Bad, and the Ugly (1966), and in the UK it was first released as Colt Concert. Italian and English-language versions of the main title song, Back Home, Someday (A Man Alone), sung by Sergio Endrigo with lyrics by Lucio Fulci, was released to help market the film.

ITALY | 1966 | 92 MINUTES | 2.35:1 | COLOUR | ITALIAN

A Mexican pistolero exacts revenge on the man responsible for the murder of his family, who has taken over his hometown in an effort to recover money that was stolen during a recent robbery.

My Name is Pecos is the least surprising of the quartet but, sometimes, one wants a film that delivers exactly what’s expected. For those wanting a great Euro-western, that’s what director Maurizio Lucidi delivers here, plain and simple. For its time, though, it would’ve offered a refreshing twist on the tried and tested western tropes, not least by having an itinerant Mexican peon as the hero and tackling the inherent racism following the white conquest of North America. The script was by Adriano Bolzoni, who’d been on the writing team for A Fistful of Dollars, along with Massacre Time’s writer Fernando Di Leo.

Italian-made westerns tend to focus on power struggles and family feuds, often employing the ‘dysfunctional Gothic family’ trope; stories that could just as easily be told against a gangland backdrop, or as generational melodramas. Partly due to the ease of access to suitable locations, and the lack of First Nation actors, spaghetti westerns didn’t do stories about the white frontiersman in conflict with indigenous Americans. If they referenced a specific historical context, it was often the American civil war or, more usually, the Mexican revolution—mainly because Latino actors were plentiful and looked the part. So, it may seem odd that they cast Robert Woods, an ‘imported’ American actor, as Pecos Martinez. My Name is Pecos was the sixth spaghetti western for Woods, so he carries the role with the cool confidence one might expect and would go on to be a major genre star.

The film opens with the wondering Mexican carrying bags and saddle as he staggers in from the desert. It seems he’s outlived his hapless horse. When he stops to drink from a well, a lone gunman notes that he appears to be unarmed, offering to sell him a gun. The wanderer buys the unloaded pistol, but as he walks away, the other man chides him for turning his back and for not introducing himself. Realising it’s a ruse to goad him into turning around, pistol in hand, he surreptitiously loads the gun with bullets from his hatband. Of course, he spins and shoots in one fluid motion and as he stands over the corpse, he replies “my name… is Pecos,” and the peasant villagers seem happy with the outcome.

There’s not a lot of character development beyond that, as Pecos plays it cool throughout as his backstory unfolds alongside the linear narrative. He finds his hometown under the control of an outlaw gang who’ve cut the telegraph lines to prevent anyone alerting the rangers. Turns out Pecos is on a trail of vengeance, of course, after his entire family was killed by the gang’s ruthless leader, Joe Clane (Pier Paolo Capponi). Pecos soon locates a barrel of loot that one of the outlaws has hidden away after double-crossing their boss, who’s in the process of tracking down the culprit with his men out and about, being mean, whilst searching for the missing money.

In most spaghetti westerns, there must be a climax where the hero is almost, but not quite, defeated before coming back ‘from the dead’ with almost supernatural powers, and this is no exception to the rule. The psychologist Carl Jung identified self-sacrifice and resurrection as an essential, archetypal motif in many myths, as well as in the life stories of several major religious figures. This is one of the many elements that position the genre within the mythic and most work best as fables.

Pecos sustains a prolonged beating but manages to stay alive by using his wits and it’s a fellow Mexican, the courageous barmaid, Nina (Cristina Iosani), who comes to his rescue. He recovers with the help of Mary (Lucia Modugno) and her father, the town doctor (Giuliano Raffaelli) who, in the past, had both his hands broken for failing to save the life of one of Clane’s favourite henchmen. Again, broken hands as a sort of castration metaphor often crop up in the psychodrama of the spaghetti western, and also in another of the films in this collection…

Tragic deaths start to mount up before a suitably shocking sequence finally tips the balance and sets the brutal finale in motion, this time involving the shooting of a young Mexican boy as he tries to intervene and stop Clane’s men from raping his sister. With its cool, understated hero, merciless murdering villains, a few truly good townsfolk, the buxom saloon girl, an ambiguous undertaker (Umberto Raho), robberies, and dirty double-crossers, My Name is Pecos ticks all the boxes.

Even at the time, it was considered a superior western and several films that followed it used the title formula of ‘My Name is…’ so it’s a little ironic that it was retitled Jonny Madoc in Germany. As was the case with Massacre Time, My Name is Pecos didn’t get an English-language release until 1968, and only after some of the violence had been cut out.

ITALY | 1966 | 83 MINUTES | 2.35:1 | COLOUR | ITALIAN

After his hands are mutilated by his former pupil during a train robbery, a performing sharpshooter trains a young man framed for the crime so that they can seek their revenge.

Bandidos is perhaps the highlight of the set with a superbly shot, strong story that blends all the right ingredients into a sort of familiar yet not quite predictable mix. The cinematography is ambitious right from the opening sequence of a well-staged train robbery. This should come as no surprise as it’s photographed by Emilio Foriscot, a veteran of the craft who began his career in the min-1930s under the direction of Massimo Dallamano who, in turn, had been Sergio Leone’s cinematographer on A Fistful of Dollars and For a Few Dollars More. Bandidos was Dallamano’s first feature in the director’s chair and his only western, though he used the pseudonym Max Dillman, presumably to appeal to the overseas market.

The previous year, Romano Migliorini had written the excellent mystery horror Kill, Baby… Kill! (1966) with Mario Bava and, here, he collaborates with Giambattista Mussetto and Juan Cobos on a meticulous screenplay with plenty of interesting twists and unexpected turns. Bandidos is as stylistically stunning as Massacre Time, but the storytelling is more assured with a near-perfect balance of enigma and ellipsis. By that I mean there are questions raised and the audience is given enough time to consider possibilities and work things out before the solution is provided, but then another mystery has been presented. The enigmas here all centre on the linked histories of three men and they follow the mythic story structure of the master and the two apprentices, the first bad and the second good. (Think Obi-Wan, Anakin, and Luke.)

Two gangs, one ‘Tex’ led by Billy Kane (Venantino Venantini), the other ‘Mex’ led by Vigonza (Cris Huerta), have banded together to pull off a daring train robbery. The ruthless massacre of all the passengers is proceeding as planned when one of them puts up some unexpectedly effective resistance. The sharpshooter showman, Richard Martin (Enrico Maria Salerno, just happened to be on board and adds a significant number of the bandidos to the bodies strewn around the tracks. Despite his superb shooting, there are simply too many for one man to dispatch and they soon arrive at an impasse. Kane, recognising the shooting style calls on Martin by name to face off in a draw and it’s clear the two men are already known to each other.

It doesn’t turn out well for Martin, but instead of killing him, Kane cruelly puts a bullet through each of his opponent’s hands, preventing him from ever handling a gun in the same way again. Then, due to the delayed getaway, Kane double-crosses Vigonza and his Mexican gang, sending them off as a decoy to cover his own tracks and lead any pursuers in another direction… what a set-up! Even if the film wasn’t included in the Vengeance Trails box set, it’s clear there’s plenty of vengeful motivation primed to play out as Kane won’t be popular with Vigonza and his gang. And why did he leave Richard Martin alive?

Bandidos is set in a Wild West rife with inequality, where life is cheap and power is won with a gun. It’s a brutal portrayal of harsh lawless times when a sheriff’s best bet for survival was to hide his badge in a pocket. Since being maimed, Martin has taken on a succession of protégés for his touring show of trick shooting, each one inheriting his old moniker of Ricky Shot. When the latest hopeful is shot dead during a performance, a young drifter (Terry Jenkins) volunteers to replace them.

As the two men bond, it gradually becomes clear that each has an ulterior motive, but also there grows a manly affection between them akin to father and son. The narrative strands never quite untangle and slowly but surely the lives of Kane, Vigonza, Martin, and now Ricky Shot, are destined to be drawn together again by the lure of vengeance.

Bandidos boasts some fantastic photography with lots of shots that typify the genre, including double close-ups facilitated by the use of wide lenses, deep focus so a hand and holster can dwarf a figure further away, stubble-clear close-ups cleverly combined in the same frame with other characters in what would be medium and long shots. Basically, Dallamano draws upon the visual language he helped to innovate with Leone for the Dollar movies.

It all makes for exhilarating viewing, but what’s more, the story’s inventive enough to hold its own and meets style with content, including a prolonged death scene that must be one of the most original in the western genre and is both macabre and amusing at once. A man has been shot with such surgical precision that his death is assured and yet he remains lucid enough to discuss the meaning of ‘The Death of Sardanapalus’, a famous painting by the revolutionary romantic artist Eugène Delacroix, that hangs over the saloon bar. The painting depicts a scene from a poem by Lord Byron in which the world-weary Sultan drinks from a poisoned chalice and it’s unclear if he does so knowingly or not. That’s not the only example of pertinent symbolism and there’s fun to be had considering the similarities and profound differences between card games and chess—both recurring motifs that have kings and queens and hierarchical power structures. Yet in one game their rise and fall may be dictated solely by chance, whilst the other is governed by a purely logical progression of cause and effect. The mirrored duality of a chess set also gives a big clue to how the finale will play out against expectations… and I shall say no more but move on to the final film presented here.

ITALY • SPAIN | 1967 | 95 MINUTES | 2.35:1 | COLOUR | ITALIAN

A man takes his revenge on the family responsible for his wrongful sentence of 10 years hard labor.

Directed by Antonio Margheriti, written in collaboration with Giovanni Addessi, And God Said to Cain is an effective mood piece; a stylistic exercise with a poetic pay-off. The events of just one day and night cleverly tell a tale that spans more than a decade using a crisp, fat-free narrative that never resorts to the use of flashback.

We meet Gary Hamilton (Klaus Kinski) on the morning of his last day in prison, having served a 10-year stretch of hard labour. He’s obviously spent every minute of that time playing out a scenario of revenge in his imagination and wastes no time putting his plans into action. By the next morning, he expects that all of those who framed him for a stagecoach robbery to be laying dead at his feet.

He travels on the same coach as young Richard Acombar (Antonio Cantafora), just returning home from service in the Union Army, and as Hamilton disembarks, he leaves his water canteen and asks that Acombar deliver it to his father and that he’d be along to visit him in person that evening. Acombar junior wrongly assumes that he’s carrying a message from an old friend.

Hamilton stops off to buy a rifle from an old hardware dealer (Franco Gulà), who obviously knows him well and sells him a particularly shiny gun he’d been saving for something special, and we learn a little about Hamilton’s motivations and the targets of his seething wrath. It seems that Acombar Snr. (Peter Carsten) not only framed Hamilton for a stage-coach robbery, he also acquired his woman, Maria (Marcella Michelangeli), who now lives with him up at the big ranch house.

With a hurricane approaching, Hamilton single-mindedly heads off to exact his revenge and by nightfall he arrives in the hometown he knows so well. Just like Dracula arriving on storm winds, Hamilton ‘blows into town’ amidst a similar pathetic fallacy. The wind and dust not only heaping on the atmosphere for Margheriti to exploit with inspired visual flair, but providing cover that helps Hamilton move without being heard and disappear into billows of dust.

Using the underground labyrinths of an ancient Indian burial ground, he’s able to move from place to place like a ghost, and the film shape-shifts into an unusual and highly successful chimera that’s as much gothic horror as it is western. Instead of secret passages beneath a castle, we have the tunnels under an old western town and its timber-built church presided over by a mute priest who consistently plays dramatic music on the organ, providing a suitable soundtrack. Is timber-Gothic a recognised sub-genre? It is now!

Although Klaus Kinski was German, he spent a lot of time in Italian pulp. A prolific actor known to accept any part if his schedule allowed, and his basic fee was met. This resulted in him having more than his fair share of interesting films, or perhaps it was his presence that made them interesting. Of course, there was a scale, and some were duds, but others turned out to be cult classics.

Kinski is one of those stars with an undeniable screen presence. He doesn’t need to do much to command attention and often his face alone is enough to draw the viewer’s gaze. With an added twitch of the lips, narrowing of the eyes, or raising of the brow, he could speak volumes. So, he’s a perfect fit for this minimal script. That face is also highly mobile and can sometimes border on the gurn. As Hamilton, though, his precise control is perfect and just skirts the expressionistic—he would’ve been a fine silent movie actor.

And God Said to Cain has succinct dialogue and nearly every line’s loaded with intimations, but for the most part, Margheriti relies on visual storytelling and the skills of cinematographer Riccardo Pallottini, who also shot Massacre Time and makes this film look beautiful, too. Most of the action takes place at night, filmed at the familiar western town at Rome’s Elios Studios, providing plenty of opportunity for dramatic lighting with the beautiful velvety darkness all adding to the baroque atmosphere. When we follow Hamilton into the comparative brightness of the ranch house, that’s also when enough light is figuratively shed on the subject. All the narrative details that’ve been hinted at and teased throughout come together and are finally revealed. It’s a film that could be used to teach narrative structure on a film studies course and should be a required text. It’s also brutally effective pure entertainment.

For such a unique movie, it does draw on a few predecessors, and the finale riffs heavily on the climatic hall of mirrors shoot-out from the Orson Welles noir classic, The Lady from Shanghai (1947). There’s a story strand lifted from The Return of Ringo, and the whole plot bears remarkable similarities, including character names, to A Stranger in Paso Bravo (1968), which if viewed back-to-back serves to show how similar material can result in both a decidedly mediocre flop and a beautifully realised masterpiece. And God Created Cain is the latter, by the way.

ITALY • WEST GERMANY | 1970 | 109 MINUTES | COLOUR | ITALIAN

directors: Lucio Fulci (Massacre) • Maurizio Lucidi (Pecos) • Massimo Dallamano (Bandidos) • Antonio Margheriti (Cain).

writers: Fernando Di Leo (Massacre) • Adriano Bolzoni (Pecos) • Romano Migliorini, Giovan Battista Mussetto & Juan Cobos (story by Juan Cobos & Luis Laso) (Bandidos) • Giovanni Addessi & Antonio Margheriti (story by Giovanni Addessi) (Cain).

starring: Peter Carsten (Pecos, Cain) • Franco Nero, George Hilton & Nino Castelnuovo (Massacre) • Robert Woods & Pier Paolo Capponi (Pecos) • Enrico Maria Selerno, Terry Jenkins & Maria Martin (Bandidos) • Klaus Kinski, Marcella Michaelangeli & Guido Lollobrigida (Cain).