Fantômas Returns! The Fantômas Trilogy (1964-67)

André Hunebelle’s beloved Fantômas trilogy, which revived the master of disguise character with a comedic twist...

André Hunebelle’s beloved Fantômas trilogy, which revived the master of disguise character with a comedic twist...

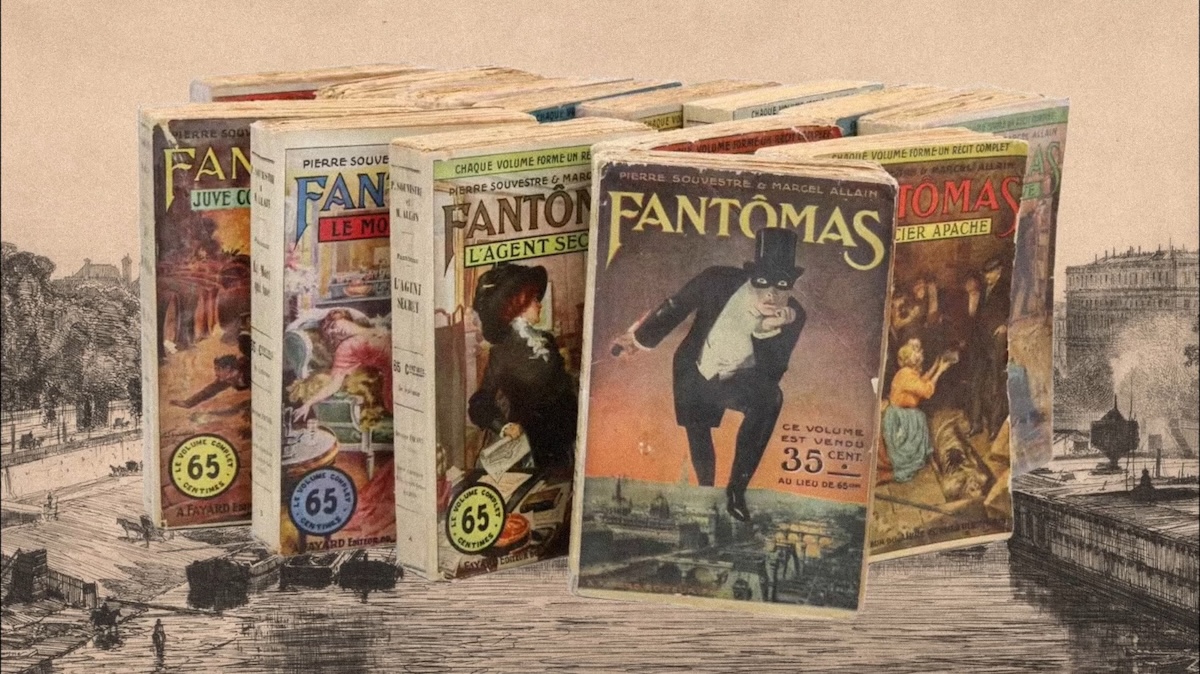

In France, the Fantômas franchise has been a phenomenon for more than a century, with books, films, and comics chronicling the anarchic exploits of the titular arch-villain. Unsurprisingly, over several incarnations and reincarnations, the character has undergone many changes since 1911, when he first appeared in a series of 32 volumes rapidly written by Marcel Allain and Pierre Souvestre and voraciously read. The original Fantômas was an embodiment of societal fears. He was a master of disguise who could assume the identity of anyone, a dark presence that lurked in the shadows and could strike anywhere at any time. Drawing some parallels with Moriarty, Conan Doyle’s ‘Napoleon of Crime’, he was an irrational genius whose only motivation seemed to be creating a climate of fear and amassing enough stolen wealth to fund his own inscrutable brand of Surrealistic sadism.

The books were so popular that they formed the basis for one of the earliest film series from genre pioneer Louis Feuillade, who directed five silent Fantômas films (1913-14). These were included in last year’s Blu-ray collection, Louis Feuillade: The Complete Crime Serials (1913-18), a landmark addition to Eureka’s ‘Masters of Cinema’ catalogue. Although those films initially installed Fantômas in the wider French cultural consciousness, they’d been neglected for so long that a new generation knew the crime lord from a 1960s trilogy of colourful and crazy action comedies directed by André Hunebelle, which are presented in this new Blu-ray box set from Eureka’s ‘Masters of Cinema’ line, resplendent in all their HD Pop-Art audacity after careful restoration by Gaumont. I’m certain a cult following eagerly awaits this Blu-ray box set.

They are often referred to as part of the Bondmania boom following the spectacular global success of Dr No (1962). This may well be the case, but their spy thriller roots reach further back than 007 to his French predecessor, OSS117—a similar secret agent who first appeared in 1949, in the novel Tu parles d’une ingénue ici OSS117 / You’re Talking About an Innocent Girl Here, OSS117 by Jean Bruce. It was a big hit and would spawn more than 80 sequels, with the later books penned by the author’s widow, Josette, as J. Bruce. Ian Fleming’s James Bond wouldn’t appear until four years later in 1953’s Casino Royal. OSS117 n’est pas mort / OSS 117 Is Not Dead (1957) was the first film adaptation, with actor Ivan Desny starring as Hubert Bonisseur de La Bath OSS 117. His British counterpart, James Bond 007, would make his screen debut five years later.

André Hunebelle had been a prolific director since the late 1940s, known mainly for comedies and swashbuckling adventures, many starring Jean Marais, who fancied himself in the role of OSS117. Amid the spy thriller boom of the early 1960s—spawned by the super-success of James Bond—-the actor approached the director with the idea of collaborating on a new, ’60s-style OSS117 movie. The result was OSS117 se déchaîne / OSS117 Unleashed (1963) but, with an eye on US markets, American actor Kerwin Mathews took the lead role.

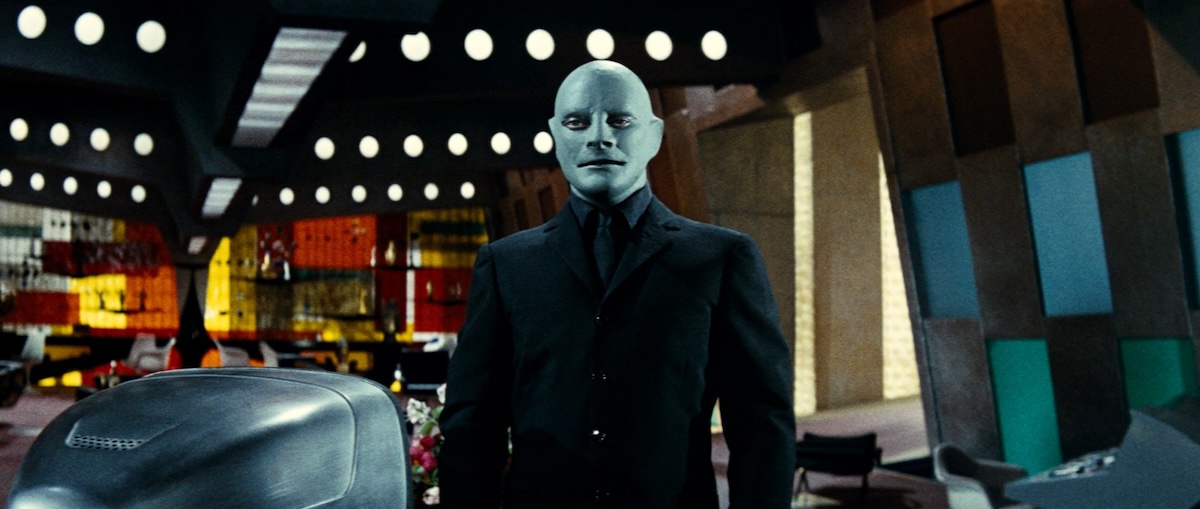

Don’t worry, Marais and Hunebelle hadn’t fallen out. Instead, their imaginations had been captured by another dormant franchise, and they were already collaborating on a new, ’60s-style Fantômas movie that would become the first of the trilogy presented here. All three star Jean Marais in the dual role as Fandor, intrepid gonzo reporter, and the fabled Fantômas—although sometimes his disguises are so convincing that the character must be played by another actor. The result is a mash-up of spy-style action adventure and crime-caper with chases across land, sea, and sky, plus plenty of gadgets and secret lairs, as the sometime slapstick cops counter the macabre machinations of a madman with camp comedy. It’s not as bad as that sounds and the trilogy is great fun with a unique personality that can be quite addictive.

Believing that Fantômas is a myth, a journalist fabricates an interview with the master criminal who turns out to be real and demands a retraction on pain of death.

Lord Beltham (Jean Marais) and Lady Beltham (Marie-Hélène Arnaud) arrive at the famous Van Cleef & Arpels jewellers in Paris in their shiny new Rolls Royce Silver Cloud III. After viewing a choice selection of ostentatious necklaces with sets of coordinated brooches and earrings, the Lord buys them all, paying a huge amount by cheque. However, not long after the couple leave, the sum on the cheque fades away and another signature appears in place of Lord Beltham’s: Fantômas.

Commissaire Juve (Louis de Funès) addresses the public via television proclaiming that although Fantômas may have a thousand faces, he has but one head… This is intended to be reassuring. Appearing on a screen within a screen emphasises that the information that reaches the public through mass media is, by that very fact, mediated and perhaps unreliable. Meanwhile, Fandor (Jean Marais) voices the opinion that Fantômas is indeed fake news, a handy myth the police exploit to distract from their failure to solve so many crimes. His press photographer colleague, Hélène (Mylène Demongeot), jokes that if Fantômas didn’t exist, you’d have to invent him. Fandor is inspired to do just that, fabricating an interview and posing for the accompanying photograph in a cemetery, wearing a ninja hood and bat cape. Here, he’s cosplaying a fusion of imagery from two of Feuillade’s famous silent krimi series, Fantômas and Les Vampires. But one can’t help think of the high camp ABC Batman series (1966-68) starring Adam West, which has plenty in common with this predecessor.

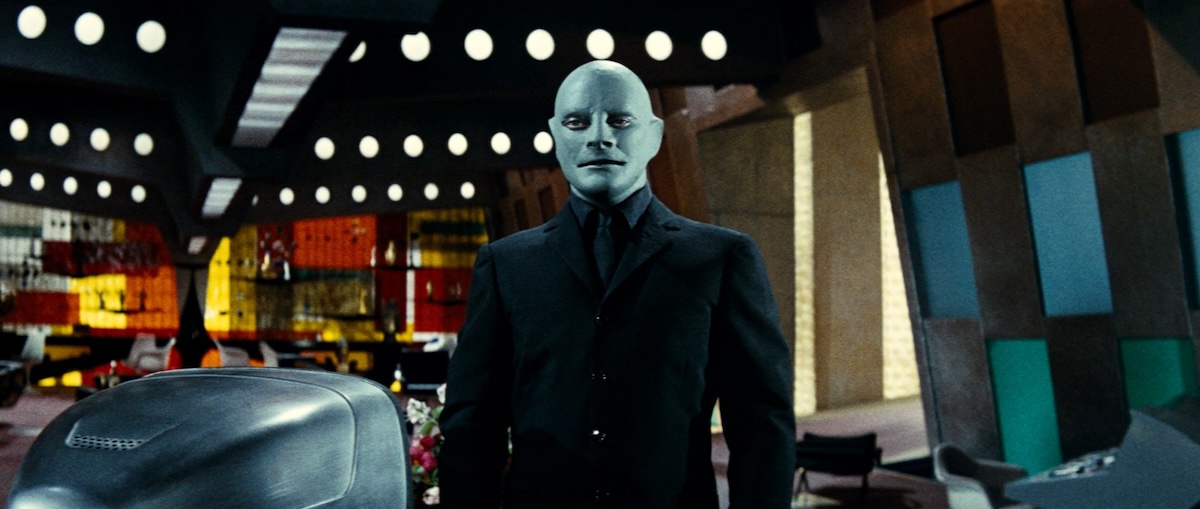

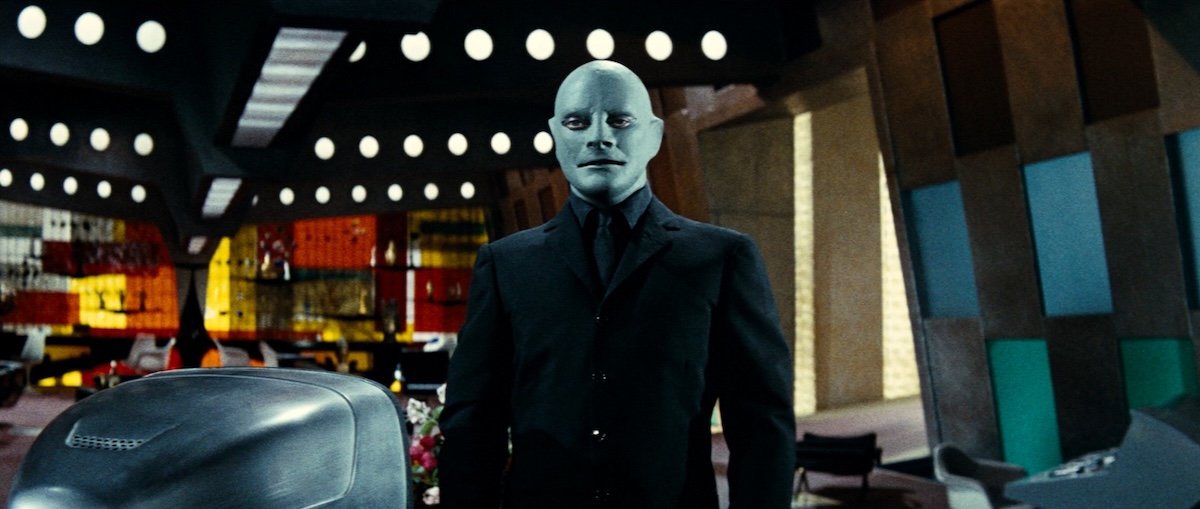

Fandor wakes up in an underground lair resembling the vaulted catacombs of a gothic cathedral, where Fantômas makes his entrance heralded by a burst of grandiose organ music. This brings to mind The Abominable Dr Phibes (1971), who would take the organ-accompanied entrance to a yet more grandiose level. Phibes readily sits in a shared lineage with Fantômas as an elusive supervillain, capable of orchestrating overly elaborate and deadly scenarios and always outwitting his pursuers. Also, the extensive use of realistic masks. In the case of Phibes, this is to look more like his old self. For Fantômas, it’s always for the purpose of deception. In his original pulp fiction manifestation, he would often take on the likeness of his murdered victims and was said to have no face of his own. Here, when not in disguise, he wears a bald, blank blue mask that I think must have been the inspiration for the performance-art collective known as The Blue Man Group, formed in late-1980s New York.

The silent Lady Beltham, always wearing stylish gowns, appears out of the light as if entering from another dimension, reminiscent of Vulnavia, the supernatural accomplice of Dr Phibes. There may not be quite as much gruesome fun to be had as the Doctor Phibes films offer, but their camp celebration of dastardly deeds and crimes staged as an art form should satisfy a similar demographic.

His ego wounded by the newspaper story that ridiculed him, Fantômas gives Fandor an ultimatum: publish a second article that honours him within the next two days, or die. To ensure that he has some good content, Fantômas plans to pull off an even more daring jewellery heist during a festival fashion show. Commissaire Juve suspects that Fandor may have connections to Fantômas, and has good reason to because the villain decides to carry out crimes wearing a mask of Fandor’s face, intended to ruin his reputation as part of his theatrical revenge.

That this film is simply titled Fantômas indicates that it’s a reboot and to expect a few changes to reflect the changing times. Some of the characters are significantly altered. In the source material, it seems that Fandor and Hélène may be siblings, the son and daughter of Fantômas—a little like the masked villain, Darth Vader, being Luke and Leia’s father. Here, they’re certainly not related by blood, leaving room for romantic potential.

Probably to appeal to a wider, family audience, the antics of Fantômas are toned down and his deeds not quite as dark as they once were. For example, in one episode of the original silent serial, he removes the skin from the hands of a corpse so he will leave the fingerprints of a dead man at the scenes of his crimes, and in general he’s gratuitously murderous. Here, though, he’s suaver and I didn’t notice anyone being killed because of his direct actions. I mean he’sstill a bad guy with a line in needless cruelty, such as claiming Fandor as his property by branding his captive with his ‘F’ monogram. But in general, this new Fantômas is meant to be fun, and as such may be too frivolous for some fans.

The once serious adversary, Commissaire Juve, is now an incompetent Clouseau-esque comic character. Indeed, Louis de Funès has a gift for physical comedy and buzzes with energy in every scene. He was already a beloved comedian and on the cusp of superstardom. By the time he’d made his third Fantômas film, he was well on his way to becoming France’s biggest movie star and most bankable box office name. A record he, apparently, still holds. So, despite Jean Marais being the action hero who performs (most of) his own death-defying stunts, Louis de Funès is more like a French Tom Cruise!

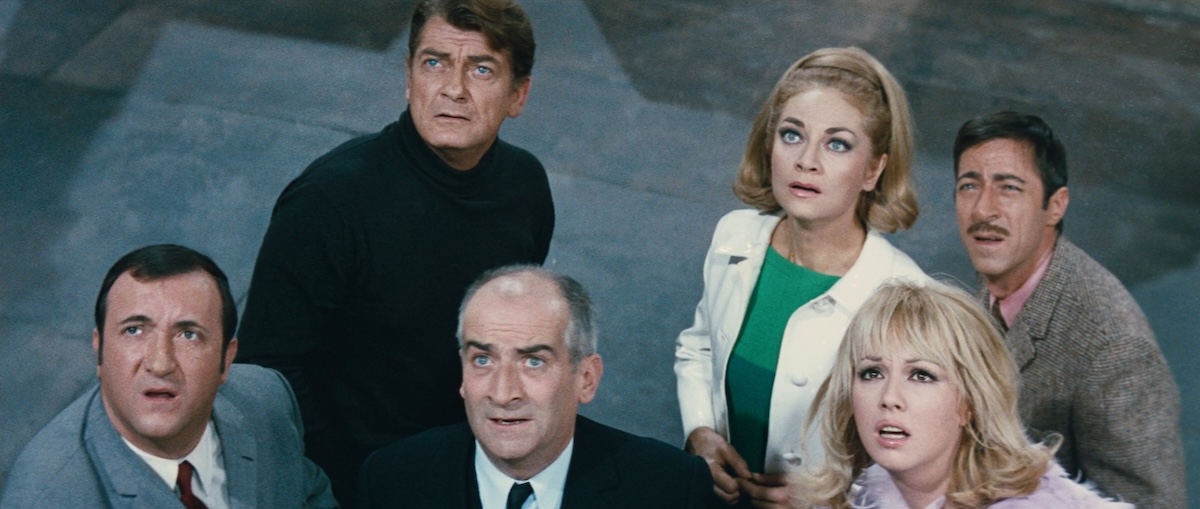

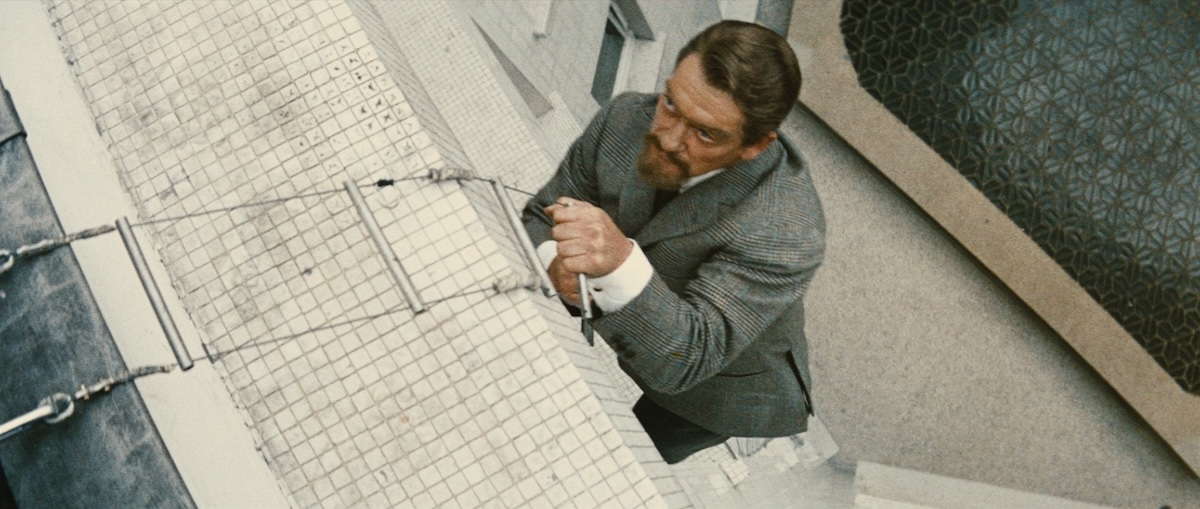

On the subject of stunts, they’re easily as impressive as anything the James Bond movies were known for, with some vertiginous crane and helicopter action and a spectacular car chase as we approach the inconclusive finale. In fact, stunt coordinator Claude Carliez and stunt driver Rémy Julienne would go on to work on the Bond franchise. So, the influence became mutual.

FRANCE | 1964 | 105 MINUTES | 2.35:1 | COLOUR | FRENCH

Fantômas plans to take over the world using an experimental weapon that will render everyone compliant and completely under his control.

For the second instalment, Fantômas ups the ante and is no longer simply accruing wealth and trying to get the better of the police—which, let’s face it, wasn’t too difficult. This time around, like any self-respecting supervillain, he’s embracing his megalomaniac ambitions for total world domination. He’s also more blasé about the lives of others. I don’t think we see him kill on screen, but his henchmen do use guns and, early on, his actions result in a nuclear research laboratory exploding without evidence of any evacuation.

In many ways, this is more of the same… but more so. The antagonist is more villainous, Juve is more comically incompetent and Fandor’s bravado is more blatant. The comedy aspect is brought more to the fore with mixed success. Juve decides to fight gadgets with gadgets, which inevitably malfunction. There’s some cleverly choreographed comedy involving Fandor impersonating Professeur Lefèvre (Jean Marais) with a realistic mask to beat Fantômas at his own game. However, Fantômas is also convincingly disguised as Jean Marais, er, I mean Lefèvre, when he infiltrates the same scientific conference to kidnap the professor who has developed a hypnotising ray that renders anyone obedient. Then, the third and genuine Professeur Lefèvre turns up, too…

With people infiltrating various strata of society and not being who they appear to be, along with the references to the nuclear age and a villainous ‘other’ vying for world power, it’s easy to read subtexts of cold war paranoia. Just like many films made in post-war Europe, such as the Bond movies, this probably reflects an unease underlying the frivolity of an economic boom. The original Fantômas books by Allain and Souvestre were the product of a similar time of stability and prosperity for France—the tail end of the Belle Époque. Yet they harked back to a period of political unrest known as the Era of Attacks in the early-1890s, characterised by anarchist violence intended to destabilise society. Their antagonist was intended as the embodiment of this threat that some felt still bubbled under the prosperous surface as Europe slowly slid toward war. Certainly, Feuillade’s treatments, made right up to the outbreak of World War I, invite this reading, but the Hunebelle reboot makes light of such themes, remaining intent on entertaining its audience, which it does with Pop Art panache.

FRANCE * ITALY | 1965 | 93 MINUTES | 2.35:1 | COLOUR | FRENCH

Fantômas introduces a tax on life itself and it’s up to Fandor, Juve and Hélène to stop him as the body count mounts.

The opening scenes establish the setting as Scotland with some location footage of kilted pipers and lochs. Apparently, this arose from a misunderstanding that Scotland Yard was in Scotland and simply referred to the police force there. I’m not at all sure of that explanation, but it sure kicks off the film with a feeling of bemusement, especially as Scotland Yard don’t feature except for a single mention in passing. The rest of the film is shot in the studio and on location in the grounds of Château de Roquetaillade, masquerading as the Scottish castle of Lord McRashley (Jean-Roger Caussimon), who will soon be replaced by Fantômas. So, it seems fitting that the location itself is an imposter.

This time Fantômas intends to tax life itself. Basically, he places a price on each day, making life itself a commodity that the wealthy must first buy in order to spend. It’s a kind of philosophical terrorism—how much is life worth and is it a commodity that the rich and powerful trade in? Again, there’s plenty of socio-political subtext to engage with, but let’s face it, the viewer’s distracted from this with some supremely Surreal spectacle.

The first film is great, the second is most welcome, but perhaps the third was one step too far. By this time, Louis de Funès was a very well-known comic actor and his presence brought with it audience expectations that he lives up to with his frenetic brand of gestural humour and silly gurning. That’s not to say it doesn’t raise a chuckle or two. While, on the contrary, Fantômas is more ruthless and murderous. He makes a point of dumping the bodies of his victims at the feet of their friends whom he has just misled by impersonating the dead.

Throughout, the performance of the principal cast have been consistently good, but one of the best things about this third instalment is that Mylène Demongeot gets a chance to shine. So far, she had been a 1960s heroine, feisty but too often relegated to the background or in need of rescuing by the male protagonist. Here Hélène comes to the fore, gets involved in some action sequences and even turns the tables on Fantômas, effectively coming to the rescue of Fandor.

The castle setting lends itself to some nice ‘Old Dark House’ horror tropes that recall classics such as Paul Leni’s The Cat and the Canary (1927) and James Whale’s The Old Dark House (1932). Of course, the fake ghosts and a spooky séance hosted by Lady Dorothy MacRashley (Françoise Christophe) are played for laughs. Although the narrative has its nastier threads, it’s also the most irreverently ridiculous, making no attempt at rational explanations for some key plot points.

For example, we’re left to work out how Fantômas constructed his underground base beneath the castle and installed a rocket silo in its tower… but do we care? Interestingly, there are some broad hints that Fantômas may not be human and perhaps his bluish skin and strangely blank features belie his extra-terrestrial or demonic origins… a fourth film was planned, but it seems that Jean Marais and André Hunebelle felt they had done enough. Perhaps it’s now time for another reboot? I, for one, would like to see a Fantômas for the 21st-century dealing with the proliferation of social media and A.I. deep fakes. Now such fake news and manipulation of the truth are so commonplace he’d have to pull out all the stops to even get noticed!

FRANCE | 1967 | 96 MINUTES | 2.35:1 | COLOUR | FRENCH

director: André Hunebelle.

writers: Jean Halain & Pierre Foucaud (based on the novels by Pierre Souvestre & Marcel Allain).

starring: Jean Marais, Louis de Funès, Jacques Dynam & Mylène Demongeot.