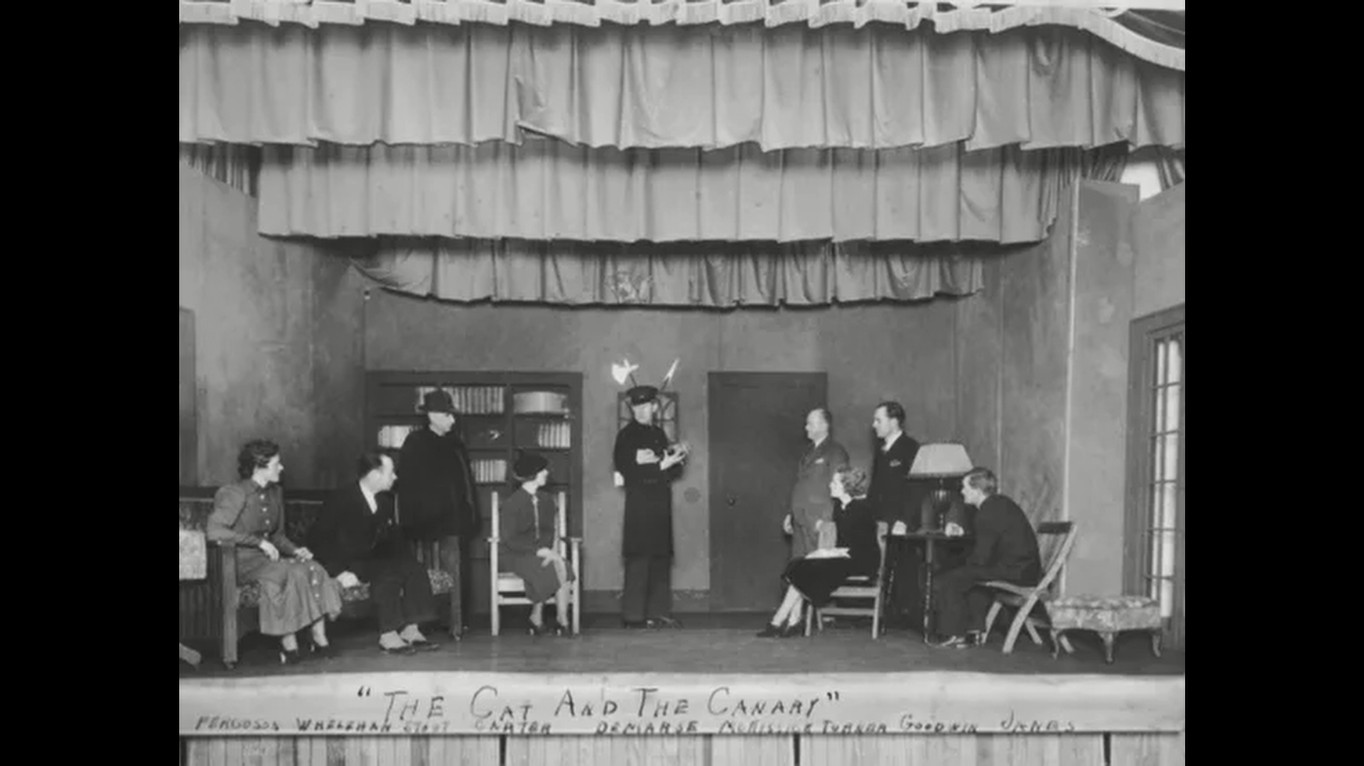

THE CAT AND THE CANARY (1927)

Relatives of an eccentric millionaire gather in his spooky mansion on the 20th anniversary of his death for the reading of his will.

Relatives of an eccentric millionaire gather in his spooky mansion on the 20th anniversary of his death for the reading of his will.

The storytelling in this silent horror-comedy is surprisingly modern, and The Cat and the Canary remains fresher than the countless imitators that followed—apart from Scooby-Doo at its best, perhaps. This beautiful 4K restoration, overseen by MoMA (New York’s Museum of Modern Art), joining Eureka Entertainment’s ‘Masters of Cinema’ collection, is still the best place to start if you want to have fun with a creepy ‘Old Dark House’ mystery. Its tropes—some of which it introduced—are now so comfortingly familiar that one would feel short-changed if any had been omitted. There are secret passages behind bookcases, hairy hands reaching from behind doors, things lurking under the bed, a monster, and perhaps even a haunted painting.

This first screen version of The Cat and the Canary is ground zero for so much of cinema history that followed. It would have developed very differently had producer Carl Laemmle not invited Paul Leni to direct. The German-born Laemmle, a true pioneer of the motion picture industry, founded the Universal Film Manufacturing Company in New York. He later moved operations to California’s San Fernando Valley, where he established Universal Studios in 1915—the biggest film production facility in the world at that time. Laemmle kept a keen eye on developments in German cinema, particularly the artistic flourishing of the inter-war Weimar period. The aesthetics of German Expressionism were exerting their influence on both stage and screen, and Paul Leni was a prominent figure working across both industries.

Leni, a professional advertising and graphic artist, had branched out into theatrical set and costume design. This naturally led to his involvement with production design for films. He went on to combine his expertise in a series of short, filmed puzzles and in staging theatrical prologues presented before the screening of films. These prologues, typically short musical performances, were intended to set the mood.

Though he’d already directed several films, his ambitious portmanteau, Waxworks (1924), was the one that impressed Laemmle. It’s among a handful of influential German Expressionist films, alongside Robert Wiene’s The Cabinet of Dr. Caligari (1920), Paul Wegener’s The Golem: How He Came into the World (1920), F.W Murnau’s Nosferatu (1922), and ahead of Fritz Lang’s Metropolis (1927).

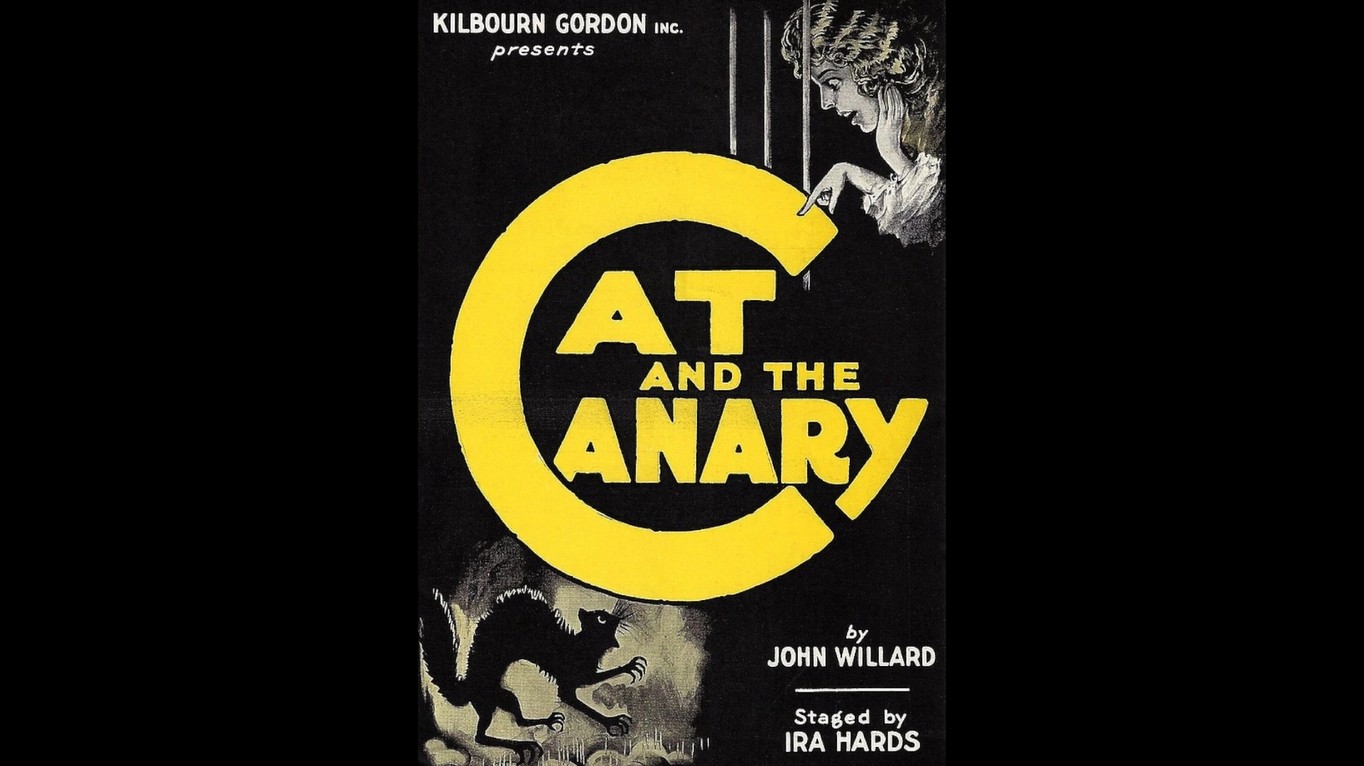

Laemmle had acquired the rights to John Willard’s hit Broadway play and hired Robert F. Hill to adapt The Cat and the Canary for the screen. Hill was a well-established writer-director of several cinematic serials adapting classic novels such as The Adventures of Tarzan (1920), The Adventures of Robinson Crusoe (1922), and Around the World in Eighty Days (1923).

Of course, stage plays rely on a great deal of dialogue, so transcribing them to the silent movie format presented a challenge. Often, such films were simply filmed versions of the plays with dialogue reduced to as few intertitles as possible. To break this mould, Laemmle needed an inventive visual storyteller who could convey character and story through actions and atmosphere—prominent features of German Expressionism. However, he made it clear to Leni that this was not to be a mere pastiche, setting him the challenge of creating a new form of distinctly American cinema…

Leni establishes the play’s premise economically during an ambitious montage. Here, the towers and turrets of a Gothic mansion morph into a cluster of bottles containing the figure of Cyrus West. We see his transformation, first from a paranoid recluse, then a prisoner of ill health from the copious medication prescribed for his physical and psychological ailments. Fearing his immediate relatives are hungry for their inheritance and eager for his demise, he sees them as cats gathered around the darkened house, menacing him like a canary in its cage. The director had already used this delirious method of multiple exposure to great effect when conjuring the otherworldly fairground setting for his Waxworks. It was a technique he would return to repeatedly.

As the old man expires, a sealed envelope floats towards the viewer bearing the words, “Last will and testament of Cyrus West. To be opened twenty years after my death.” This begs the question: why wait two decades? The enigma is immediately compounded when a second envelope appears labelled thus: “This envelope is never to be opened if the terms of my will are carried out.”

Then we’re presented with what might be the earliest example of what would become known as the ‘black-gloved killer’ trope, so strongly associated with the giallo genre decades later. We watch through the eyes of the anonymous perpetrator as a pair of gloved hands open a safe and tamper with the envelopes inside. Right from the start, hands—gloved or otherwise—become a recurring motif, providing a wealth of clues and red herrings for the observant viewer.

Next, the camera transforms into a disembodied presence, haunting the West Mansion. It explores its empty chambers, starkly shadowed—this does more than simply set the scene; it tells us upfront that the mansion itself is a crucial story element. Briefly, we are lost and alone, until we find Mammy Pleasant (Martha Mattox) carrying a meagre lamp down a corridor lined with billowing drapes. She answers the door to Mr Crosby (Tully Marshall), the family lawyer, and the pair make a wonderfully unnerving duo. Their oddly timed mannerisms are enhanced by spooky under-lighting, apparently achieved by cutting out sections of the set’s floor to create lighting pits that also facilitate some striking use of low-angle camerawork.

Already, we have a significant change from the source material. No longer is Mammy Pleasant a blackface caricature of a scary crone, as she was in the play, but a Creole woman with a sinister voodoo-from-the-bayou atmosphere. It seems that Hill and Leni felt the institutionalised racism inherent in the original character didn’t sit well with their vision for a new American cinema.

The film’s version of the character is altogether more ambiguous, but remains one of the scariest things about the movie. Mattox underplays her effectively with hand-wringing, stern stares, and a way of gliding through a scene like one of Dracula’s brides. However, she also delivers a couple of easily missed but meaningful smiles. We know she knows something… or at least thinks she does.

The lawyer has summoned the surviving relatives of Cyrus West for the reading of the will, which will commence at the stipulated time of midnight on the 27th of September, 1921—the year the original play was published. The first of the hopefuls to arrive is Harry Blythe (Arthur Edmund Carewe), whose hand we meet first, extended through an open door to be clasped by Crosby’s. We only get to see the whole of Harry as recognition dawns on the lawyer. Next to arrive is Charlie Wilder (Forrest Stanley), who removes his gloves as he enters the room but must be coaxed into shaking Harry’s hand, as there is clearly an old grudge between them.

The next to arrive on the increasingly blustery night are Cecily Young (Gertrude Astor) and ‘Aunt’ Susan Sillsby (Flora Finch). Although a storm is brewing, the taxi driver refuses to drive onto the estate and drops the two women at the main gates. When questioned about his reasons, we get the first of several inventively animated intertitles: the word “Ghosts” spelled out in wobbly typography. And as the women finally reach the front door, their words slide down the screen like phantoms: “Gosh, what a spooky house!” Walter Anthony receives credit for the titles, but I suspect the actual animation of the text was done by a technician, or perhaps Leni himself.

The two final attendees to arrive are Paul Jones (Creighton Hale), who brakes sharply to avoid a black cat in the road. Mistaking the resulting blowout for a gunshot, he runs the remaining distance, arriving in a fluster. The aforementioned cat is obviously a stuffed prop, but it’s unclear whether this is merely shoddy effects or if it had been deliberately placed there by a scheming villain to unnerve Paul, who is quickly established as the easily agitated and ‘nervous type’.

Shortly afterwards, Annabelle West (Laura La Plante) arrives, and the group soon gathers to hear the reading of the will. It’s a classic set-up popularised by the novelist Agatha Christie, who by the mid-1920s had already written a few bestselling whodunit mysteries set in isolated environments, featuring a small group of characters, any one of whom could be victims or culprits. If you’ve ever played Cluedo, you’ll know exactly what I mean.

The late Cyrus West stipulates that his entire fortune be divided amongst those present who still bear his family surname. Ah, now we realise why the captions had been so meticulous in telling us the full names of each character—the entire inheritance, including the house and family jewels, will go to Annabelle. However, there is a proviso that the beneficiary be deemed of sound mind. Understandably, the others are disgruntled and, if so inclined, may well plot to engineer a diagnosis of insanity for Annabelle by the time the doctor (Lucien Littlefield) arrives to assess her, first thing in the morning.

It’s now a well-worn plot device, most famously reused in Thorold Dickinson’s Gaslight (1940)—-another film adapted from a play that features missing jewels which could incriminate a culprit—and from which our modern term ‘gaslighting’ originates. For The Cat and the Canary, there’s an added complication when an asylum warden (George Siegmann) arrives looking for an escaped maniac known as ‘The Cat’ because he tears his victims to shreds with clawed hands, just as a cat would do to a canary. The warden informs the gathering that he tracked his quarry to the main gates and ‘The Cat’ could already be inside the house with them…

Bearing in mind that this is a silent film from the early days of Hollywood, it’s still a surprisingly effective mood piece. Paul Leni is certainly trying his hardest to impress and secure his future in Hollywood. For the time, his roving camera and unusual angles would have been impressive, considering the weight of the equipment. So too would his inventive use of contrast, which foreshadows (forgive the pun) the later noir style, and one spooky scene is lit by hand-held torches.

Of course, credit must also go to his cinematographer, Gilbert Warrenton, and even more so to production designer Charles D. Hall. Hall, drawing on Paul Leni’s German Expressionist roots, gets to showcase his baroque style through sets and props—to such an extent for the first time. Be sure to take a moment to admire his chairs, clocks, and corridors. He would return to work with Leni on The Man Who Laughs (1928) and The Last Warning (1928), and would later help define the early gothic horror films made by Universal, including Tod Browning’s Dracula (1931), James Whale’s Frankenstein (1931), and The Bride of Frankenstein (1935).

The Cat and the Canary is certainly entertaining throughout and would make a fun Halloween film. I’ve watched it with teenagers and pensioners alike, and it never fails to entertain, but I’m sure both the comedic and horror elements have lost much of their bite. Some of the scenes that would have been terrifying are now chuckle-worthy, but that said, others remain genuinely creepy and aspects of the final reveal are still quite chilling. The comedic sequences will raise a smile for certain, but anything more than that will depend on one’s sense of humour. If you enjoy physical comedy, then Creighton Hale, who generally played beefier heroes, doesn’t disappoint. At times, his antics, which never quite stray into slapstick, reminded me of Matt Smith’s more manic moments as the Eleventh Doctor.

There’s little doubt that The Cat and the Canary is the progenitor of Scooby-Doo and contains everything a classic episode does—except for the Scooby Gang themselves. However, I could draw some clear parallels with the protagonist, Paul Jones, who is a very early, if not the first, iteration of the ‘cowardly hero’ trope. A baton that Scooby and Shaggy picked up and still carry with pride!

John Willard wrote his original play as he recovered from PTSD after fighting in the trenches of World War I and, though he milks it for comic effect, his reasoning had a deeper meaning. John realised that heroes are just as scared as anyone and he and his comrades trembled with fear as they bravely charged onto the battlefield. The Willard-penned Channing of the Northwest (1922), a romantic melodrama that segues into a crime thriller featuring bootleggers, had been produced during the first years of the prohibition, yet he was not brought in to adapt his own play.

In addition to his writing duties, Robert F. Hill was also on set as a liaison for Leni and to act as a translator for the director, who only had a smattering of English at the time. The newspaper reporter and novelist Alfred A. Cohn (who would go on to become the Los Angeles Police Commissioner) also had a hand in the script, although he’s better remembered for adapting the first talking picture, The Jazz Singer (1927), in the same year. Cohn would be reunited with Leni as part of the writing team on The Last Warning, another moody whodunnit starring Laura La Plante, who was a huge star at the time. While not a true sequel, The Last Warning was intended as a companion film to The Cat and the Canary. The two films bookended Paul Leni’s Hollywood career, as he was to die of an untreated tooth abscess within a year of its completion.

Between these classics, Paul Leni directed two further films for Carl Laemmle. The Chinese Parrot (1927) was the second film, now lost, in a series of Charlie Chan mysteries. However, his most remarkable achievement was the epic adaptation of Victor Hugo’s classic novel, The Man Who Laughs. Although he died before horror became established as a cinematic genre, Leni’s films with Laemmle are acknowledged as templates for what would become known as the Universal Classic Monsters cycle, beginning with Dracula. This film would almost certainly have been directed by Leni had he lived.

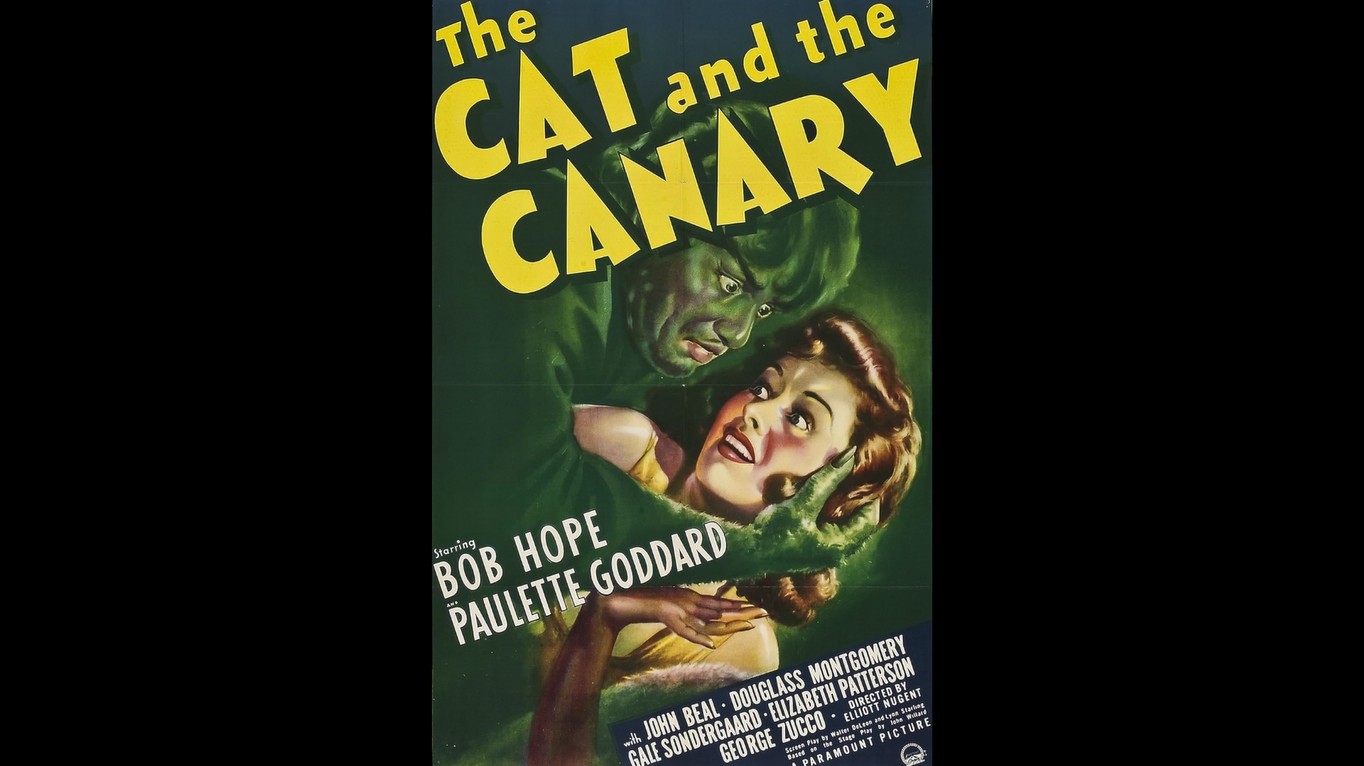

Just like the Broadway play, the screen version of The Cat and the Canary was a big hit. Universal considered it such a hot property that their first two talkies were remakes: Rupert Julian’s The Cat Creeps (1930) and The Will of the Dead Man / La Voluntad del muerto (1930), a Spanish-language version directed by George Melford and Enrique Tovar Ávalos. Both those versions are now lost, but The Cat and the Canary has been remade several times since, along with many other loose adaptations of the same source material. The most notable are the 1939 version directed by Elliott Nugent and starring Bob Hope and Paulette Goddard, and the 1978 British colour remake directed by Radley Metzger, which leaned more towards horror than comedy and increased the body count.

USA | 1927 | 82 MINUTES | 1.33:1 | BLACK & WHITE (TINTED) | ENGLISH (SILENT)

director: Paul Leni.

writers: Alfred A. Cohn & Walter Anthony (story by Alfred A. Cohn & Robert Hill; based on the play by John Willard).

starring: Laura La Plante, Creighton Hale, Forrest Stanley, Tully Marshall, Gertrude Astor, Flora Finch, Arthur Edmund Carewe, Martha Mattox & George Siegmann.