BROTHERHOOD OF THE WOLF (2001)

In 18th-century France, the Chevalier de Fronsac and his Native American friend Mani are sent to the Gevaudan province to investigate a mysterious beast.

In 18th-century France, the Chevalier de Fronsac and his Native American friend Mani are sent to the Gevaudan province to investigate a mysterious beast.

Those who haven’t seen Brotherhood of the Wolf / Le pacte des loups don’t know what they’re missing. A truism, perhaps, but anyone fresh to the sophomore feature of unpredictable director Christophe Gans is in for a rare treat. That’s if they’re looking for an action-driven period drama in which horror and martial arts collide with romance, intrigue, political machinations, and plenty of surprises. An ambitious, some might say audacious, blend of different genres and styles that gel into a cohesive whole around an intricately braided narrative with countless twists and turns. It’s a challenge to describe and discuss Brotherhood of the Wolf without giving too much away, but as this wonderful new 4K Ultra HD Blu-ray, director-supervised restoration from StudioCanal may draw-in a fresh crowd, I’ll avoid major spoilers.

The film opens with an impressive crane shot that seamlessly takes us down the façade of a castle and through a window into the chambers of Count d’Apcher (Jacques Perrin); a shot that’ll be echoed during the climax, bookending the movie. As the last living soul to know the truth behind the Beast of Gévaudan, the old Count is in the process of penning his memoires. Immediately, another clever technical transition rushes the viewer into the past where little time is wasted getting to the attention-grabbing, high-impact slaying of a hapless shepherdess who’s dashed against rocks by a powerful, yet unseen assailant of superhuman strength. We will soon learn that she’s not the first victim of a killer with a predilection for young women and children.

From one violent scene we move straight into another as a group of thugs—men disguised as women—brutally beat an old man (Philippe Nahon) and his wild daughter (Virginie Darmon) on a rain-drenched hillside. They’re interrupted by two mysterious riders who appear like mythic heroes from a spaghetti western and then proceed to dispatch the muggers in a spectacular display of kung fu.

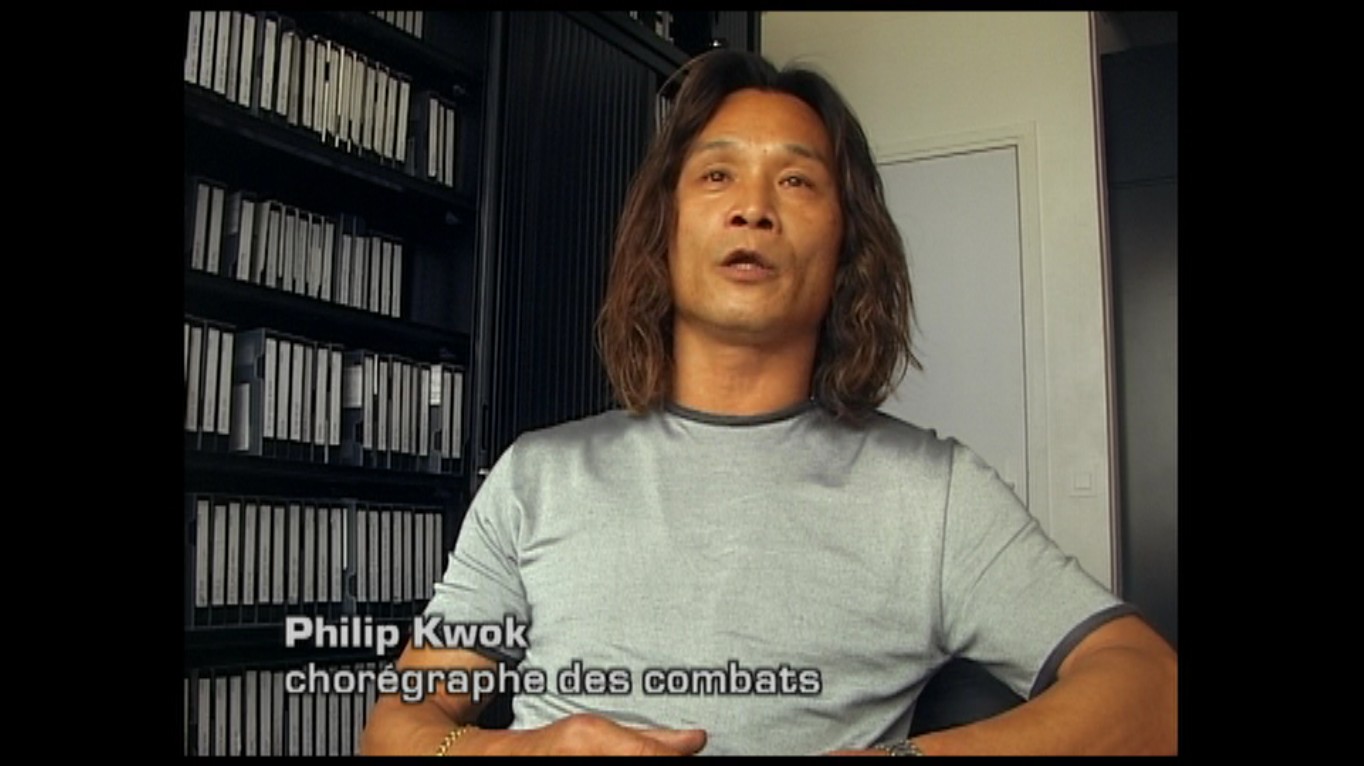

Okay… we’re only five-minutes in and already we’ve moved from historical drama to martial arts action movie by way of a Hammer horror style slaying of a ‘buxom wench’. Perhaps too much for some audiences to take, but each element is consummately executed and segues smoothly. We’re clearly in the hands of an inspired and capable filmmaker. The fight scene in the rain is also well-choreographed by Phillip Chung-Fung Kwok, a veteran of Hong Kong’s Shaw Brothers productions since the mid-1970s. It’s also tightly edited for maximum impact and visually spectacular, exploiting the dynamic potential of splashing mud, blood, and sparkling spray. This sets the bar for further increasingly spectacular fight scenes to come.

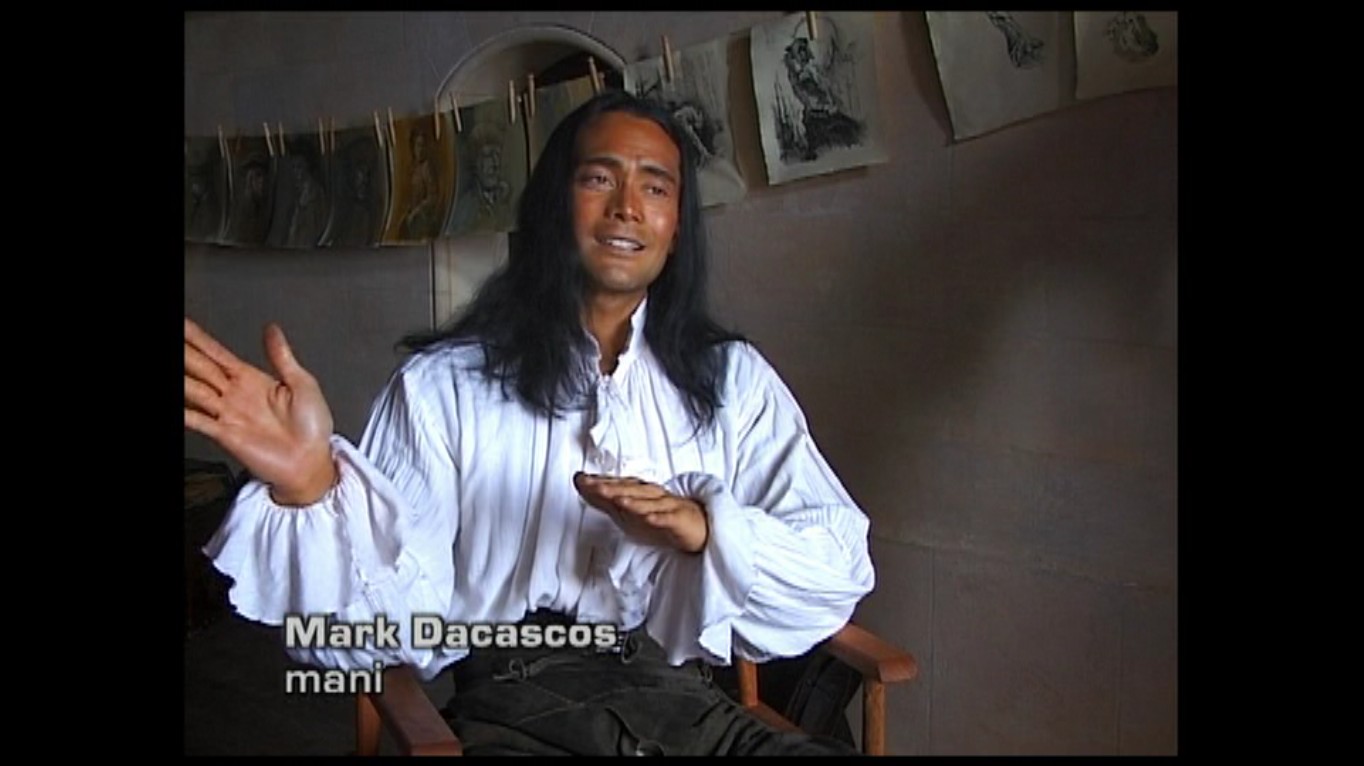

When the two heroes are greeted at their destination by the Marquis Thomas d’Apcher (Jérémie Renier), it’s revealed they are Grégoire de Fronsac (Samuel Le Bihan) and his companion Mani (Mark Dacascos). Fronsac is the King’s botanist and naturalist, sent to Gévaudan to capture or kill the Beast. Mani who’d been his Iroquois interpreter, had accompanied him back to France after they were both caught-up and deeply scarred by the atrocities of colonial war against the English and the indigenous population across the Atlantic, in what was then called New France.

The Beast of Gévaudan is a celebrity among connoisseurs of cryptids and folklore. Just as criminologists are endlessly fascinated with Jack the Ripper because the culprit was never caught, historians and cryptozoologists continue to speculate what monster was responsible for the spate of killings as it was never conclusively identified. It’s of historic document that something rampaged through the rural French province of Gévaudan in the mid-18th-century, with around 300 deaths finally attributed to ‘The Beast’.

In contemporary accounts of the 1760s it was invariably described, by the few who survived its attacks, as a wolf-like, cow-sized creature, with disproportionately large jaws and fangs… most were sure that whatever it was, it was not a wolf. Theories abound from a giant rabid wolf, an abandoned mastiff trained for war, a large exotic predator escaped from an aristocrat’s menagerie to more outlandish suggestions of werewolves, demons, and the devil himself. Hunters eager to earn a reputation converged on the region and several presented impressive wolves they’d shot, claiming them to be the Beast. Although some were found to have human remains in the stomachs, the killings didn’t abate. It’s known that wolves rarely attack humans and when they do, it’s almost exclusively a rabid one. However, the survivor’s who’d been mauled or bitten by the beast did not succumb to rabies and the terror continued for years despite many wolves being culled.

It became one of the earliest ‘breaking news’ stories, its infamy spreading internationally along with tabloid-style exaggeration and mythologising in numerus lurid retellings and depictions in popular prints. Hysteria built to such a pitch that finally, King Louis XV felt he had to intervene and offered a huge reward that attracted hunters from all over and beyond France. The monarch also sent Royal troops to comb the countryside and supplied two of his professional hunters who managed to shoot the enormous ‘Wolf of Chazes’ which was stuffed and presented to the Royal Court at Versailles in the autumn of 1765. The King proclaimed the matter concluded. Yet the killings in Gévaudan continued until 1767 when the Marquis d’Apcher, a local nobleman, hired a specialist hunter and organised another hunt which appears to have been successful. The affair was kept low-profile so as not to contradict the King and thus be seen to challenge his authority. The killings ceased.

Inspired by these historic events, Brotherhood of the Wolf proceeds to build on the legend, blurring fact with fantasy, in a cleverly convoluted tale that touches upon themes of colonialism and cultural clashes, as well as the power struggles between different factions in the French aristocracy and the authority of the church, examining their complicit roles in preserving power by controlling knowledge and perpetuating ignorance and fear among the masses. Don’t worry though, at no point does it become preachy or didactic and the underlying seriousness never gets in the way of an exciting and entertaining romp adorned with the visual beauty of an art movie.

Stylistically, Brotherhood of the Wolf owes much to several notable precursors. The arrival of Fronsac and Mani as special investigators is reminiscent of Franciscan friar William of Baskerville (Sean Connery) and his novice, Adso (Christian Slater) arriving at the ‘cursed’ monastery in Name of the Rose (1986), but with added kung fu fighting, and both films reference the classic Sherlock Holmes mystery, The Hound of the Baskervilles, by way of Terrence Fisher’s 1959 adaptation for Hammer.

The gorgeous, naturalistic cinematography by Dan Laustsen recalls folk horror classics like Witchfinder General (1968), The Last Valley (1971), and The Wicker Man (1973). Laustsen had attracted the attention of Gans with his work on Ole Bornedal’s Nightwatch (both the 1994 original and 1997 remake) and on Guillermo del Toro’s Mimic (1997). He’d work with Gans again on Silent Hill (2006) and become known as del Toro’s go-to cinematographer, doing excellent work on Crimson Peak (2015) and The Shape of Water (2017). He’d also be reunited with Mark Dacascos for John Wick Chapter 3: Parabellum (2019).

The other stand-out visual element of Brotherhood of the Wolf is the sumptuous costume design by Dominique Borg. In keeping with his painterly approach throughout, Gans insisted the costumes not only be period accurate but carefully coordinated with other aspects of the mise-en-scène, right down to such details as background extras being dressed in complimentary or contrasting colours to the actors in the fore. Or the soldiers’ uniforms matching the seasonal colours of the natural environment and riders being coordinated with their horse. In many ways, the costumes assume the duty of set, especially in the otherwise natural exterior locations.

Perhaps, though, Brotherhood of the Wolf owes the greatest stylistic debt to Francis Ford Coppola’s Bram Stoker’s Dracula (1992), with which it shares cinematic vocabulary, not least in the casting of Monica Bellucci as a mysterious courtesan who just might be a special agent sent by Rome, apparently possessing supernatural powers and a knowledge of poisons and potions to rival Lucrezia Borgia. Clearly her presence adds to the overall visual pleasure, but she’s not simply there for decorative reasons and is one of four key female characters who definitely drive the narrative.

The female lead is taken by the excellent Émilie Dequenne in just her second role after impressing with her debut in the title role of Rosetta (1999) that picked up the Palme d’Or and won her ‘Best Actress’ at the Cannes Film Festival. Here she’s Marianne, the unobtainable object of Fronsac’s affection and sister to the overly protective, somewhat ambiguous Jean-François (Vincent Cassel) who is by turns rakish, charming, dangerous, and worrying. It’s an edgy performance that captures aristocratic arrogance and assumed entitlement. In contrast Fronsac is a rational and enlightened figure reflecting the broader historical context of the mid-18th-century. It was a time of turmoil and change in France, marked by the rise of Enlightenment philosophies and the decline of feudalism. Fronsac can be seen as embodying this new age of reason, science, and progress that threatened the old establishment as the nation teetered toward revolution.

The entire cast deliver subtle, perfectly pitched performances and much of the narrative is conveyed not by dialogue but by how they look at each other. Gradients of power are eloquently expressed in all exchanges between different social strata, class hierarchies, genders, and when Mani is present, are racially charged.

Gans doesn’t shy away from conveying the bigotry of 18th-century France which is confronted head-on during the party scene where Mani is ‘presented’ almost as a form of entertainment. It could be argued that the portrayal of Mani as the wise, mystical guide for his ‘white saviour’ is problematic as this would be a tired trope that harks back to the Lone Ranger and Tonto, grounded in colonialist attitudes. More astute analysis reveals that, if anything there’s a reversal here and Mani is indeed the saviour of Fronsac. The relationship between these blood brothers is the thread that binds all the whole complex narrative together and Mani is key to several resolutions and reveals throughout and is the catalyst for the exhilarating, OTT action in the final act. Although he is ‘the other’, he represents the nobility and spiritual purity absent in the surrounding society—totemism not tokenism.

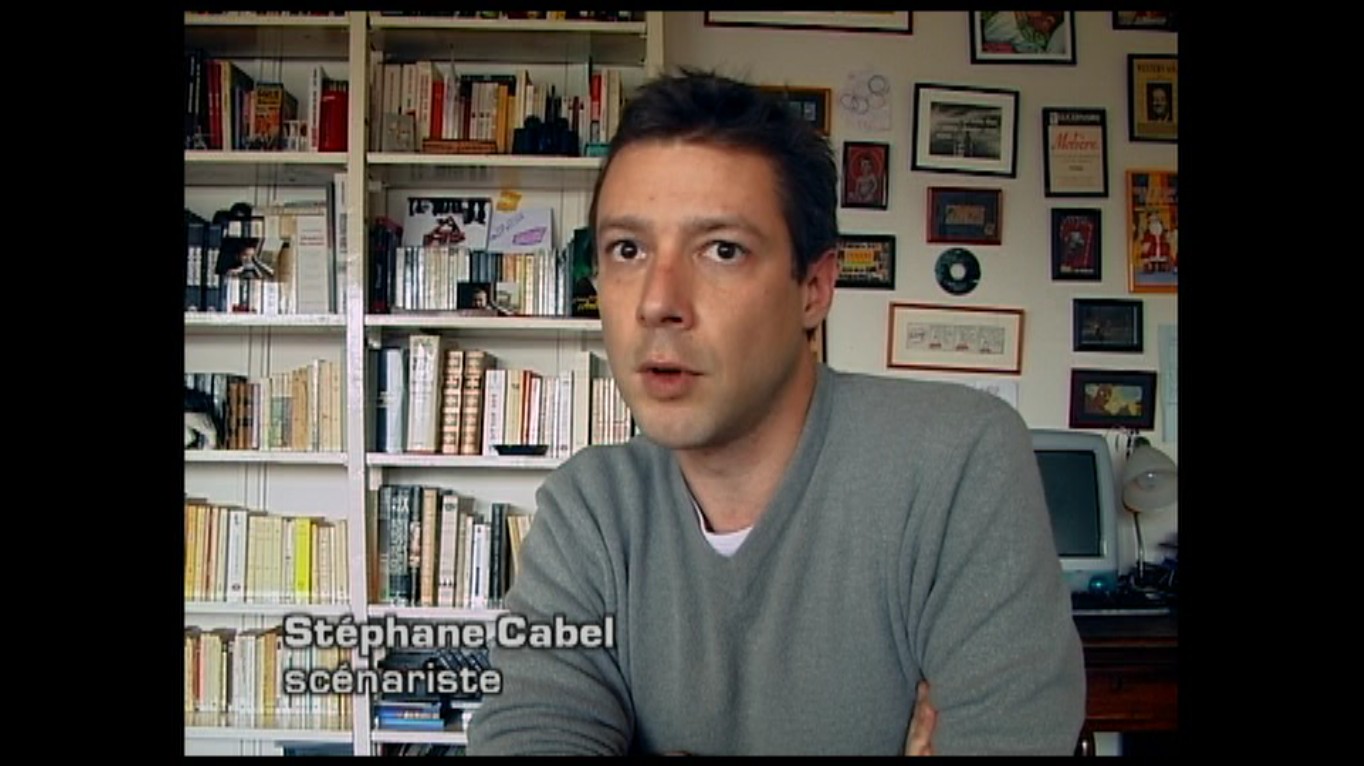

Apparently, Mani is what convinced Christophe Gans to take on the project. Although the character was barely a cipher in the original script by Stéphane Cabel, he expanded it into the central role with actor Mark Dacascos in mind, after they’d worked so well together in Crying Freeman (1995), the director’s debut feature. Dacascos brings his spiritual poise and martial arts prowess to the part, but also a stillness that speaks of a greater latent power linked with the land and the life force it supports—seemingly in communion with a wild wolf that may be Mani’s spirit in animal form. Despite minimal dialogue, he manages to convey deep emotions with the subtlest changes of expression and a simple glance can be as expressive as any spoken line.

Apparently, director Christophe Gans instructed the principal cast to study Stephen Frears’ Dangerous Liaisons (1988) as part-preparation for their roles here. He’s a self-confessed cinephile and readily admits that his films contain plenty of references, citing Terence Fisher, Mario Bava, and Dario Argento as key inspirations along with Jean Cocteau’s La Belle et la Bête (1946) which is deliberately quoted in some of the statuary added when filming on location at Chateau Roquetaillade and Christophe Gans would remake with Vincent Cassell as ‘The Beast’, in 2014.

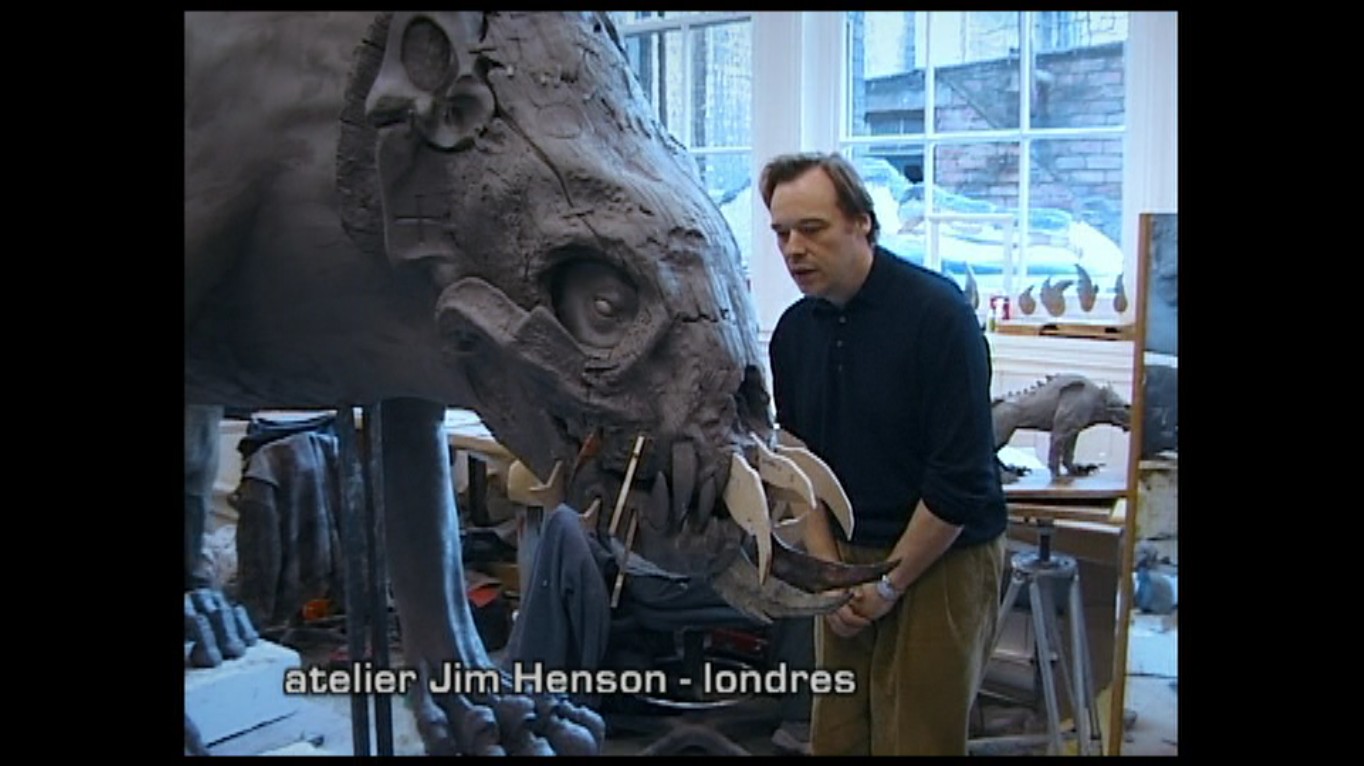

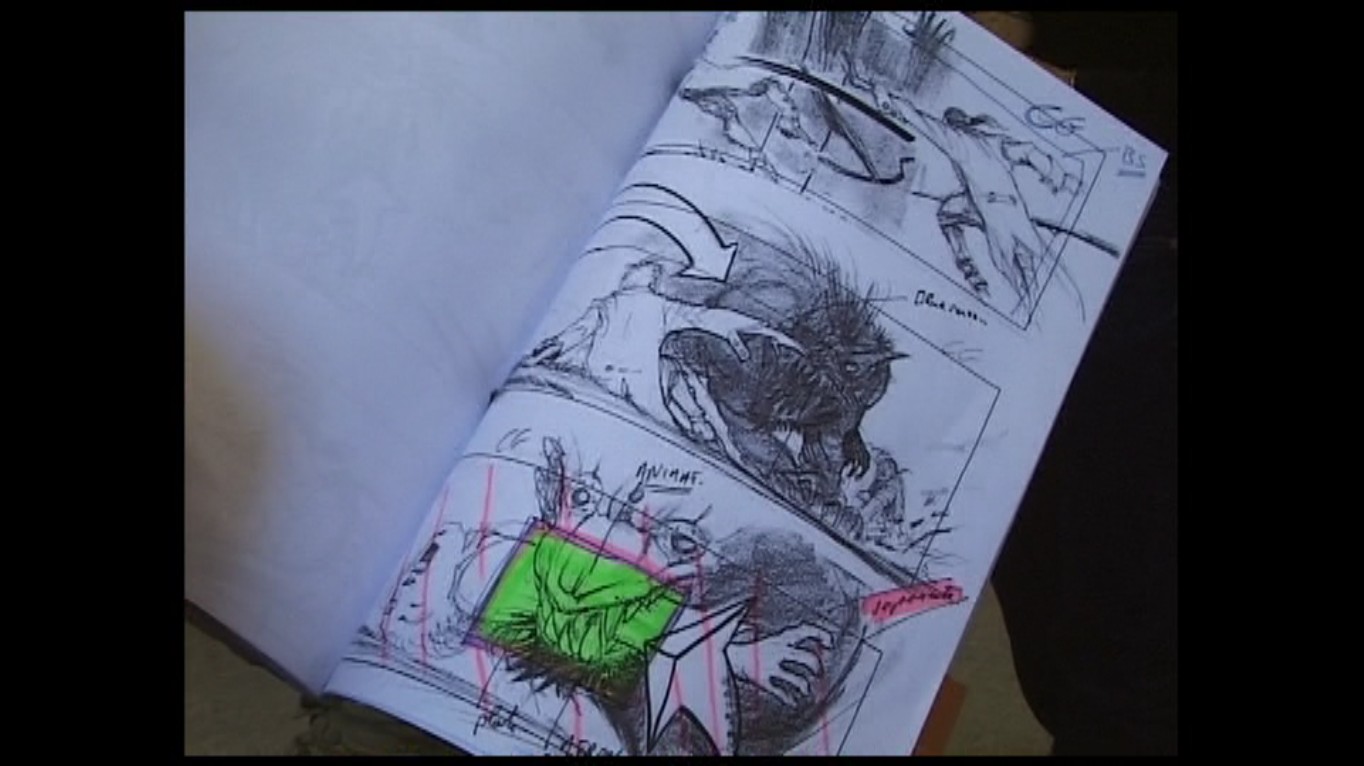

Gans maintained authenticity by filming entirely on location, apart from one scene involving a performative set that had to fall apart in a precisely choreographed sequence to match the rampaging animatronic and digital beast courtesy of Jim Henson’s Creature Shop. For the most part, the chateaus and villages are all real locations, though often composited from different places. The ruins of the Templar castle where several key scenes take place was purpose-built in the forest of Barbizon, based on visual reference from 19th-century Romantic history paintings of the period. As the film progresses, he also introduces expressionistic sculptures of trees and their exposed roots into the natural settings to incrementally add to the sinister atmosphere and metamorphose them into fairy tale forests. Because of this reliance on filming in the open, unseasonable weather both added to the drenched atmosphere and delayed filming causing the shoot to go overschedule and overbudget.

Although its theatrical release was a box office success in France, earning an impressive $24M, it took a little longer to earn back its final budget of $29M but went on to become one of the 10 most successful French language movies of all time, adding takings of more than $70M with US distribution and doing well in the home entertainment market where it established a cult following.

FRANCE | 2001 | 155 MINUTES (DIRECTOR’S CUT) | 2.33:1 | COLOUR | FRENCH • GERMAN • ITALIAN

director: Christophe Gans.

writers: Stéphane Cabel & Christophe Gans.

starring: Samuel Le Bihan, Vincent Cassel, Mark Dacascos, Émilie Dequenne, Monica Bellucci, Jérémie Renier.