THE BLAIR WITCH PROJECT (1999)

Three film students vanish after travelling into a Maryland forest to film a documentary on the local Blair Witch legend, leaving only their footage behind.

Three film students vanish after travelling into a Maryland forest to film a documentary on the local Blair Witch legend, leaving only their footage behind.

“Iconic” is the most overused word in journalism today, but The Blair Witch Project is a rare case where it applies. Still controversial after two decades, it brought a horror subgenre to mainstream attention: the found-footage movie. This 1999 hit was the progenitor of endless parodies and a whole academic subculture, but also a classic case of a zero-budget film created by amateurs that swept aside Hollywood blockbusters.

Above all, it deeply disturbed much of its audience with a kind of visceral terror rarely encountered before. Although some found it boring, incomprehensible, or plain annoying. It remains divisive to this day; a modern classic people either love or hate, but one rarely has no feelings about The Blair Witch Project.

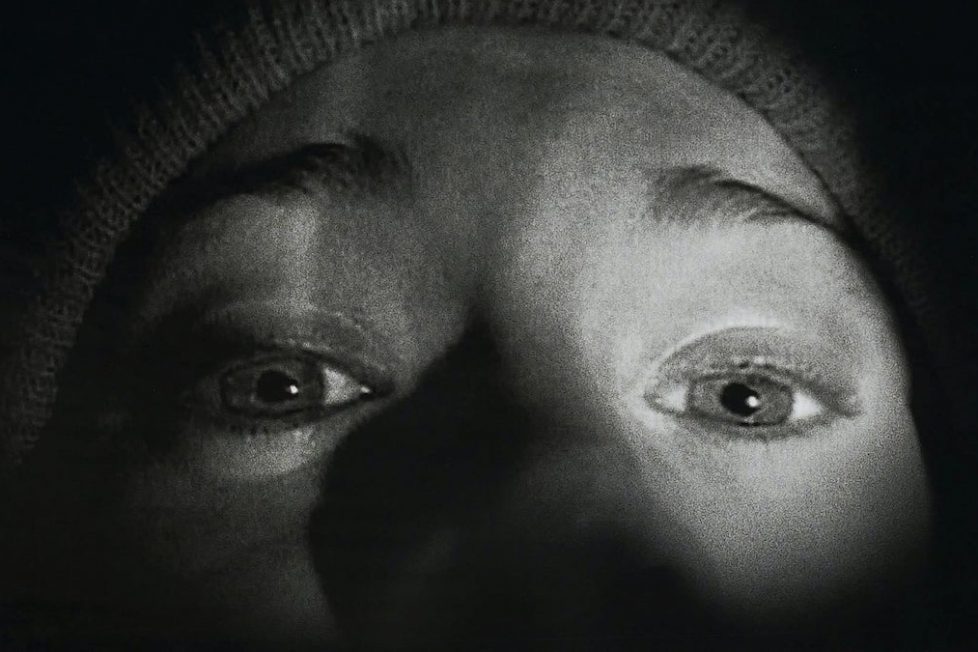

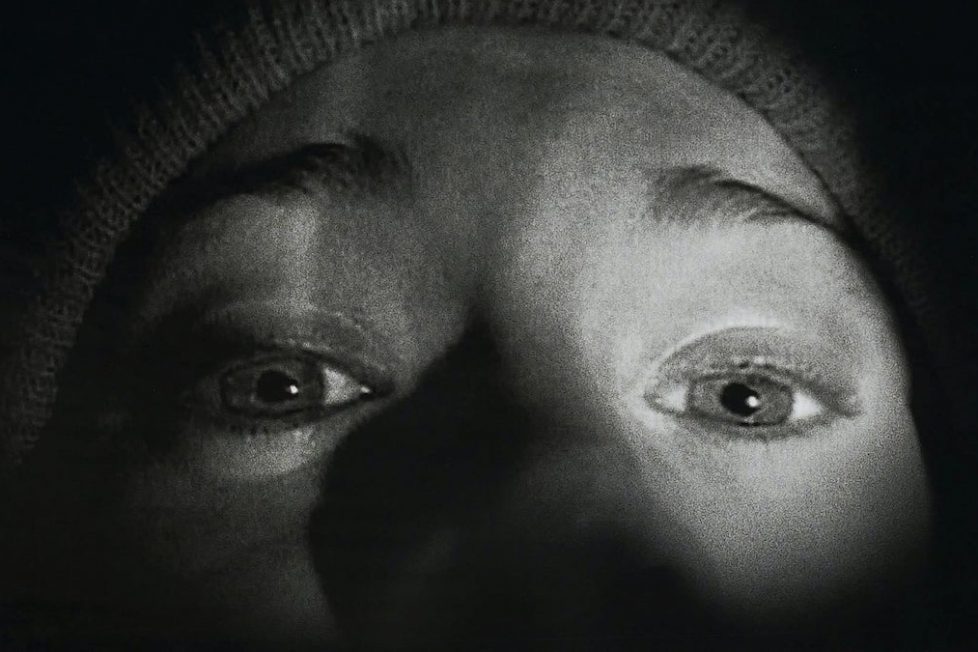

As iconic as the film itself is, its most famous segment—a monologue to the camera, where actress Heather Donahue apologises for misjudgements she believes have doomed her and her friends—encapsulates what was remarkable about Blair Witch. There was an unknown and ordinary-looking actress, sans makeup, turning the camera on herself. Most of her face isn’t even visible in the frame because Donahue held the camera at the wrong angle, but her error made the final cut. The rest of the image is completely black—there’s no lighting because there’s no crew around, and the pervasive eeriness of Blair Witch comes from what’s not seen. Terror lurks in the vast dark space stretching beyond the edges of the screen… as unknown to the characters as it is the audience watching them.

Most importantly, Heather’s terrified and her desperation feels real. This emotion, too, is part of cinema legend because the three main actors endured, as close as humanly possible, the actual experiences being depicted. They genuinely trudged through thick forest and stumbled upon sinister stick-men… they camped out overnight while being kept awake by strange sounds… they grew cold, hungry, and tired… and all the while they filmed themselves going through hell.

Of course, the extent to which they “really” lived these experiences is debatable. Just as it’s questionable how many people in the audience truly believed this film was telling “a true story” despite the media hype. Donahue, along with her equally unknown co-stars Joshua Leonard and Michael Williams, obviously knew she was making a movie and presumably surmised the stick-men and ghastly noises were part of an elaborate set-up by her directors. Although the filmmakers and crewmen didn’t directly accompany the actors during shooting, there was occasional contact being made through notes, infrequent face-to-face encounters, and a CB radio.

Even so, Blair Witch’s style felt novel. It was guerrilla filmmaking taken about as far as it could be, combined with a fictional narrative that shaped the entire movie. The handheld cameras weren’t just cheap stand-ins for more sophisticated equipment, they’re at the heart of the story. The negligible production values and the fact no effort is made to conceal it only contributed to our suspension of disbelief: audiences unconsciously thought “no professional filmmaker would deliberately shoot a film so badly, or script dialogue so clumsy, so it must be real“. Similarly, because the film doesn’t definitively say that a witch exists, that—perversely—makes us less likely to deny the possibility outright.

The premise of The Blair Witch Project is incredibly simple. Three film students from Montgomery College in Maryland—Heather, Josh, and Mike—are making a documentary about a local legend dating back to the 19th-century: the Blair Witch. The movie consists of the footage they’d recorded on two devices (a Hi8 video unit and a 16mm film camera), as an opening title notes the students were never seen again after entering the woods to work on their documentary film. Only the footage you’re about to see was found a year later, inexplicably buried beneath a house.

The students interview townsfolk in Burkittsville (a small community in the area where the witch supposedly lived) and later traipse into a local forest to find a murder site from the 19th-century allegedly involving the sorceress. They camp in the woods, not intending to stay long, but soon become lost. And then they start to find increasingly sinister objects with magical or ritualistic purposes (rock cairns, stick-men hanging from trees), as nerves start to fray as they become desperate to find their way home.

The nights only get worse. Something attacks their tent in the darkness. One morning, one of them goes missing. Further disconcerting sights, sounds and discoveries—none of them ever fully explained—torment the remaining two students. On their last night in the forest, they discover an old house and decide to enter. What then ensues in this brief final episode of the movie isn’t clear.

Reasonably convincing analyses online and in print have explained the “evidence” of their last minutes of footage as indicating that Heather is being attacked by… well, something… and that Michael shortly will be and, in the circumstances, it’s difficult to be optimistic about the fate of Josh who’d vanished earlier. However, the movie itself offers no interpretation of the footage, any more than it conclusively demonstrates much at all. There’s no evidence of a witch or anything else supernatural existing in the forest, or even that the filmmakers are dead.

It is what it is, and audiences are left to read into it what they will—aided, for some, by an extensive back-story the producers provided on the film’s official website and through a tie-in documentary called Curse of the Blair Witch, which aired on the Sci-Fi Channel (now Syfy) a few weeks before the movie’s US premiere. These weren’t just marketing add-ons, however. Although the film is effective on its own, the website and documentary are essential to the concept of the movie and key to its success in ’99. Originally, co-directors Daniel Myrick and Eduardo Sánchez, who conceived the project in the early-1990s as students in Florida, had intended the found footage to be only part of a longer mockumentary about the witch and the disappearance of the students.

Although they abandoned this plan, the idea of creating a complex back-story persisted—to explain the origin of the witch through events from the late-19th-century right up to the police hunt for the missing trio. All this detailed information dropped from the film itself was instead utilised on the website, TV documentary, and book The Blair Witch Project: A Dossier. The Blair Witch Project was thus a pioneer not only in film but in the way it utilised the internet in its early days. Indeed, some argue the official website should be heralded as the primary creative product and this film and the documentary merely support it.

20 hours of footage were shot over eight days on location in Burkittsville and in the woods of a state park approximately 30 miles away. Blair Witch famously cost only $60,000 to make, with $10,000 of that coming from independent producer John Pierson (host of TV show Split Screen), who became involved after he’d been shown sample footage of the concept. His involvement doubtless aided the movie’s acceptance into the Sundance Film Festival, after which Artisan Entertainment bought the distribution rights.

Here, however, the legend of Blair Witch’s minuscule budget gets hazy, because Artisans spent a great deal more than the original $60,000 on further work to the movie. Among other things, they wanted alternative endings shot (though none were used) and went big on its all-important marketing. Indeed, Sánchez has estimated the final cost of the film to be between $500-750K, although other estimates differ. This is still a tiny sum by the standards of the Hollywood mainstream but not so meagre for an indie production.

Whichever number you accept, with a box office gross of just shy of $250M, Blair Witch was one of the most successful films of all time in terms of return on a dollar of investment. Although most lists rank one of its found-footage successors, Paranormal Activity (2007), even higher. (For comparison, if Avengers: Endgame had enjoyed the kind of box-office-to-production-cost ratio of Blair Witch, it would’ve earned the entire GDP of a medium-sized country!)

Outside the box office performance, though, critical opinion was split. Many critics loved it. Roger Ebert called it “extraordinarily effective”, Peter Travers of Rolling Stone claimed “I have seen the new face of movie horror and its name is The Blair Witch Project, a groundbreaker in fright that reinvents scary for the new millennium”, and Blair Witch was that year’s only US prize-winner at the Cannes Film Festival after winning the ‘Prix de la jeunesse’ intended for young filmmakers.

But many others were less convinced. Andrew Sarris thought it “represents the ultimate triumph of the Sundance scam: Make a heartless home movie, get enough critics to blurb in near unison ‘scary,’ and watch the suckers flock to be fleeced.” The film academic and historian Peter Brunette believed that “critics are so desperate for something different that they’ll root for anything even slightly offbeat.”

Its longer-term legacy was very mixed, too. Two sequels, Book of Shadows: Blair Witch 2 (2000) and Blair Witch (2016), weren’t much liked by audiences or critics. The careers of its creators never hit the stratosphere, either, though Sánchez and Myrick both directed several minor features afterwards. Leonard has continued to appear in movies, impressively so in Steven Soderbergh’s Unsane (2018); Williams had a few more roles but now works as a school counsellor; and Donahue left acting to grow medical marijuana and published a book about it called Growgirl: How My Life After The Blair Witch Project Went to Pot.

However, if the individuals involved failed to set the big screen alight again, the influence of Blair Witch cannot be underestimated. It was effectively responsible for the found-footage style going mainstream with the likes of Cloverfield (2008) and Paranormal Activity, most famously, but also with August Underground (2001) and Septem8er Tapes (2004), as well as more recent offerings like Unfriended (2014) and Searching (2018). All of these are direct inheritors of the Blair Witch success. Countless analytical articles and learned tomes, like Found Footage Horror Films: A Cognitive Approach, wouldn’t exist without Sánchez and Myrick’s movie. The fiction-played-straight website concept has been copied, too, for example by Blair Witch producer Gregg Hale’s Fox TV show FreakyLinks (2000-01).

Myrick and Sánchez didn’t come up with their idea out of thin air, of course. Orson Welles’ famous War of the Worlds radio broadcast in 1938 utilised much the same concept of presenting imaginary events in a documentary style; Bram Stoker’s novel Dracula (1897) recounts its story through letters, diaries, and newspaper articles; even Daniel Defoe’s Journal of the Plague Year in 1722 is fiction posing as fact.

On-screen, found-footage had been employed as early as 1980 in the horror-shocker Cannibal Holocaust, and indeed just a year before Blair Witch’s ’99 release a similar story was told in a very similar way in The Last Broadcast (1998)—the coincidence briefly generating controversy over Blair Witch’s originality. (In fact, Myrick and Sánchez had started their project long before they could’ve possibly seen The Last Broadcast.) The persistent myth of snuff movies underlined the connection between found footage and horror, while the rise of reality TV perhaps made audiences more willing to accept unpolished, slice-of-life material as entertainment.

Quite apart from its style of presentation, Blair Witch also explores some potent themes. The deadly house in the woods clearly echoes fairy tales. The premise of city slickers getting fatally lost in the great outdoors has a strong pedigree in US cinema, from Deliverance (1972) to The Edge (1997). The production style seems to reject high tech but, at the same time, the movie is based around an obsession with technology and the need to record everything—which was a growing issue in the late-’90s. The main protagonist and antagonist (Heather and the witch) are both women, in a genre largely viewed by men. And, of course, there’s a certain meta amusement in the way that a movie about people completely cut off from information and the world nevertheless so cleverly exploited the web.

But primarily, Blair Witch succeeded—and still succeeds when seen today—not because of these subtleties, or its novelty value, but because it uses every aspect of a relatively unfamiliar format to hammer home a terrifying tale. It makes a virtue of not having much money for VFX and on-screen violence. It was so different from standard 1990s horror that we found it difficult to say “oh, it’s just a movie” to settle our nerves. The disorientation produced by the handheld cameras and the alternating colour and black-and-white footage enhanced our sense of being lost. The absence of adequate light at many points just makes the noises we hear even scarier.

Perhaps most important of all, the film is right there in the woods with its characters from the first frame to the last. There are no shots from other vantage points allowing us to distance ourselves from what’s happening. Every image is from a character’s POV and, as Myrick has said, “the editing and the way the film is shot don’t let you escape.”

Indeed, for the millions who’ve seen The Blair Witch Project over the years, there are only two reactions: either you wonder what all the fuss was about, or it grabs you and holds you mercilessly in its grip. Trees in the moonlight will never seem quite the same again…

writers & directors: Daniel Myrick & Eduardo Sánchez.

starring: Heather Donahue, Michael C. Williams & Joshua Leonard.