DUNE: PART TWO (2024)

Paul Atreides unites with Chani and the Fremen while seeking revenge against the conspirators who destroyed his family.

Paul Atreides unites with Chani and the Fremen while seeking revenge against the conspirators who destroyed his family.

“Fear is the mind-killer. Fear is the little-death that brings total obliteration.”

These words define the final moments of Denis Villeneuve’s opus Dune: Part One (2021), a landmark achievement in science-fiction adaptations that concludes with the annihilation of House Atreides. Manipulated by the whims of Emperor Shaddam Corrino IV (Christopher Walken), Leto Atreides (Oscar Isaac) and his entire clan have been massacred by the vicious House Harkonnen. This scorched-earth trail of death relinquishes control of the desert planet Arrakis to the Harkonnens’ barbaric rule, granting them unfettered access to melange, the superhuman ‘spice’ that controls the socio-political landscape of the known universe. With this resource, the Harkonnens could become the most influential force known to humankind, a terrifying prospect to anyone who knows of their unrelenting brutality towards all who oppose them.

Among the few who’ve managed to escape are Paul Atreides (Timothée Chalamet) and his mother Lady Jessica (Rebecca Ferguson). Now residing with the Fremen, the indigenous people of Arrakis who are deeply familiar with the desert’s ways, they are both in hiding.

The Harkonnens believe Paul and Jessica to be dead. This necessitates their constant evasion as the Harkonnens attempt to exterminate the Fremen from Arrakis to resume unfettered production of the psychotropic substance known as ‘spice’. However, this conquest is fuelled by a significant underestimation of the Fremen’s strength. As Paul and Jessica discover, this underestimation may cost the Harkonnens their dominion over Arrakis.

Here is where the latter half of the above quote re-emerges: “I will face my fear. I will permit it to pass over me […] Where the fear has gone, there will be nothing. Only I will remain.” In the context of the first part of Villeneuve’s sprawling adaptation of Frank Herbert’s novel, that final sentence is a sign of Paul and Jessica’s survival, an indicator of how they are the last remnants of the annihilated Atreides family, even through conspiratorial adversity.

However, in Dune: Part Two—the technically astoundingly and masterfully terrifying latter half of Villeneuve’s vision for Herbert’s novel—that fear is turned on its head. The final sentence (“only I will remain”) is now an ominous threat, evoking the image of a mighty ruler, standing triumphantly on the bodies of the conquered.

Indeed, Paul and Jessica are no longer the victims of that fear. As they gain an understanding of the breadth of the Fremen’s power and their unique link to clairvoyant and superhuman abilities, fear is weaponised, becoming a tool they can wield. Part One is the story of a family crumbling under a crisis caused by forces beyond their control. Part Two is the story of a clan amassing fanatical power, becoming a force beyond all control. It’s an incredible tale of overwhelming devotion, a film that, both aesthetically and thematically, commits to that devotion just as much as the Fremen who gradually fall under the rule of Paul Muad’Dib Atreides. He’s no longer just the Duke of his family; he’s on his way to becoming the nascent messiah, not only for the Fremen but for the entire known universe.

Aesthetically, Dune: Part Two showcases Denis Villeneuve at his peak, as if the scale he established for Arrakis in Part One simply wasn’t enough for discerning audiences and fans of Herbert’s original novel. Villeneuve’s finest sensibilities, even from his earlier sci-fi films—the impact of the prescient premonitions in Arrival (2016) and the oppressive dedication to powerful aesthetics in Blade Runner 2049 (2017)—now have the opportunity to fully merge with his already gargantuan vision for Arrakis, ultimately creating some of the most overpowering visuals the auteur has ever crafted in his career. Given the sheer range of experiences already crammed into the 165-minutes of this immense cinematic work, it’s impossible to identify a single starting point. Further bolstered by the fact that, unlike Part One, all of Part Two was originally filmed using large-format IMAX specifications, there’s a sense of unparalleled scale that Villeneuve has never achieved to this overwhelming extent before.

The vastness of Arrakis’s sands is further emphasised by boldly warm shades and razor-sharp chiaroscuro, which is further accentuated by the brutalism of the architecture built on its surface. The shadows creeping through the underground passages of the Fremen add to this effect.

Giedi Prime, the host planet of the Harkonnens, is lit by a “black sun” so unnatural that the film undergoes a reverse Wizard of Oz (1939) effect, with its outdoors being monochrome. This leads to the striking effect of the characters’ skin fading to an infrared-like black and white as they walk outside of the barely coloured environments.

Meanwhile, the lush forests, ornate architecture, and diverse weather of the Emperor and Princess Irulan’s (Florence Pugh) home planet emphasise the opulence of their dominion over the Great Houses. With an increasing number of impressionistic, almost psychedelic sequences triggered by intensifying premonitions for the protagonists, Villeneuve delves deeper into his already striking visuals and special effects, achieving an uncanny level of intimacy within the frame. By employing extreme close-ups, he draws the viewer into the scene with an incredible degree of immersion.

It’s important to mention upfront the film’s unparalleled focus on creating a work of unimaginable scale. This is crucial because it underpins the story’s exploration of devotion in all its forms. The spectacle becomes an indispensable tool for conveying how easily individuals succumb to intense belief and faith. Dune: Part Two derives immense power from its complete dedication to this concept. For those who believed that the first part’s scope and scale were primarily spectacle for spectacle’s sake, the spellbinding formal advancements made in this incredible sequel demonstrate how they can serve the narrative of zealous piety. This is a rare strength, born from the film’s commitment to both story and aesthetics.

Indeed, mustering such a level of devotion is the central focus of Paul and Jessica’s quest for newfound power. In particular, Jessica, already a member of the intensely powerful clairvoyant collective known as the Bene Gesserit, gains access to further supernatural strength through Fremen rituals and traditions. She uses these to steadily devise a plan to gather more Fremen to join Paul’s cause, conducting surreal, telekinetic conversations with her unborn daughter, Alia, to achieve this. However, Paul’s conflict throughout the film stems from the prophetic role he believes has been unfairly thrust upon him. He initially prefers to let the title of messiah pass him by, relinquishing the responsibility of leadership to one of the Fremen themselves whenever possible. Yet, Jessica’s prophetic and increasingly successful efforts to bolster Paul’s following, further spurred on by the dedicated, often humourous zeal of the religiously devout Fremen leader Stilgar (Javier Bardem), continue to throw spanners in the works of Paul’s denial. Eventually, the pressures and enemies encroaching upon him, coupled with the Fremen, force him to accept the destiny that awaits him. This transforms him into something far more terrifying than anyone could have anticipated.

On the other side of this devotion lie the Harkonnens, all of whom work solely in the pursuit of attaining power and influence through whatever ruthless means are necessary. Beast Rabban (Dave Bautista), their brutish leader, is tasked with running spice production on Arrakis following the Atreides’ annihilation. He marks his already burgeoning career with nothing less than short-tempered rage and brutality. All the while, Baron Vladimir Harkonnen (Stellan Skarsgård), the ever-scheming monster spearheading the House’s operations, continues to devise strategies to ensure the Harkonnens can attain ultimate imperial influence across the universe.

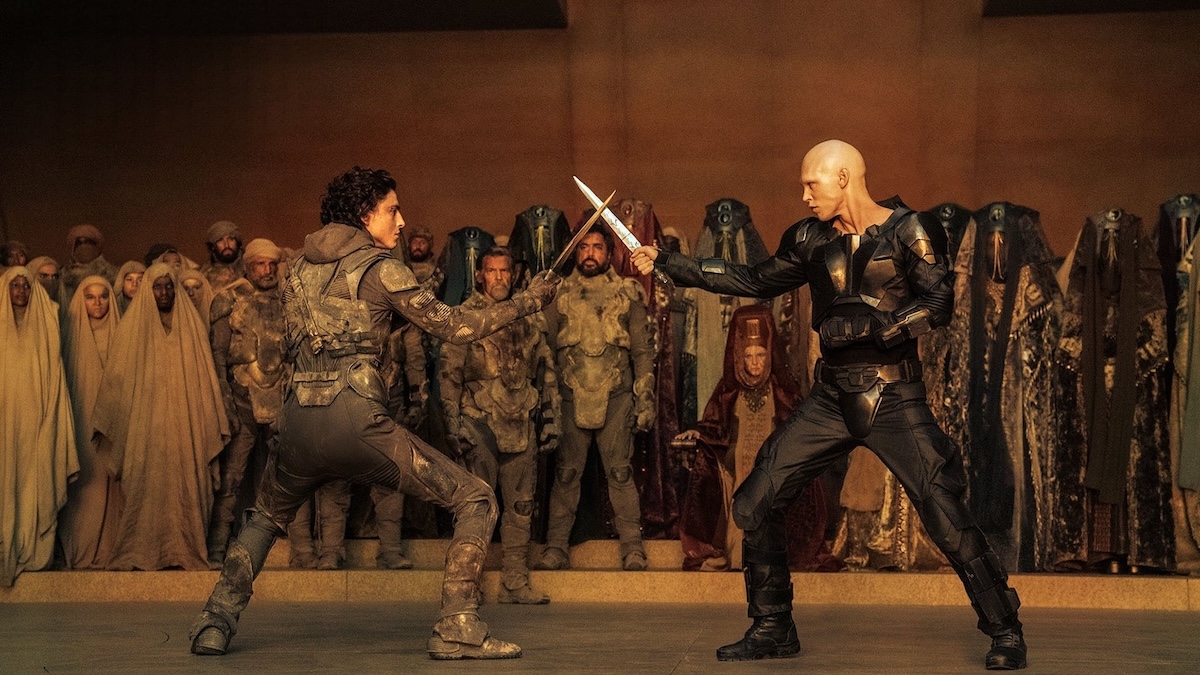

His main conduit? Na-Baron Feyd-Rautha Harkonnen (Austin Butler), the relentlessly cruel and sadistic heir, is crowned in what might be the villain introduction of the century. A sensory-overwhelming gladiator match sees tens of thousands cheering him on in a triangular arena, as he animalistically hunts down his weaker Atreides foes to eviscerate them. At times, he drools like a rabid hyena in the relentless pursuit of his prey, all while Hans Zimmer’s score violently pounds, blares, and screams, amplifying Feyd’s entrance and the ensuing carnage. Power is the Harkonnens’ god, to which they devote every ounce of their faith, resources, and ruthlessness. This faith is set to collide with the messianic faith of the Fremen, as their conflict intensifies further.

What this inevitably results in is a full-scale war of unparalleled scale, in which everyone has a role to play. All characters previously featured in Part One receive their fair share of shocking developments throughout Part Two, introducing striking moral complexities in the latter half of the story.

Ferguson, for one, having now unlocked Jessica’s full potential as the Reverend Mother of the Fremen, exhibits a level of command and charisma far beyond the limited levels that Jessica could only unleash while under the control of the Bene Gesserit. It’s at once a display of unmatched, reflexive telepathic strength that coincides with a show of unforeseen confidence, to be reckoned with as she is unshackled by Fremen traditions from the restrictions previously placed on her.

Bardem, above all others, feels most like a Fremen native, even in the way he carries himself during sandworm rides and treks through the desert. His ease into the role of an indigenous leader is so remarkably naturalistic that even the sentences he speaks in the Fremen language all feel like they come from nothing less than lifelong, fluent comprehension and intuition.

Meanwhile, Zendaya brings a level of resistance to Chani that isn’t normally exhibited in her depictions from the book or other adaptations. She fully understands here that Chani’s romantic bond with Paul adds a further moral dilemma to her character. Chani contends with having to fight against Paul’s gradual corruption by messianic power while remaining continually devoted to securing the Fremen against encroaching threats. Yet here, she realises that even with the prominence of the Emperor and the Harkonnens, the real threat might be emerging from within as Paul’s influence rises. This itself could be a potential response to criticisms of the “white saviour” trope that emerged after Part One introduced Paul’s rise to power among indigenous people.

“This prophecy is how they enslave us!” she blurts out. Given the fervour with which the Fremen dedicate their entire lives to Paul, it’s not entirely out of the question.

And while Butler is a new character in this cast, he’s easily the highlight amongst Dune‘s rogues’ gallery of antagonists. Formerly infamous for his Elvis voice, Butler has now graduated to a more youthful impression of Skarsgård’s Baron. This is just one indication among many of how Butler carries the sinister cunning of Feyd’s uncle, alongside a sadistic fervour for domination and bloodshed that only Feyd himself could generate.

However, it’s Chalamet who definitively delivers the greatest surprise amongst this cast. Throughout Part One, Chalamet and his portrayal of Paul seemed to be the weak link in the cast. On paper, he’s not given much to do beyond learning why and how the Atreides and the Harkonnens are battling, and eventually fleeing Arrakeen while his family is being massacred, all the while suffering fitfully from visions of a predetermined future.

But from the moment Paul first raises his voice in command of something early in Part Two, one might quickly begin to understand just how much of a surprising fit he might be for the role of Messiah. And when he finally reaches that point, it is a display of absolute influence, truly a sight to behold.

Few films that grapple with a fervent, fanatical faith in a messianic figure ever truly capture why, or how, people devote everything to figures of seemingly limitless influence. Villeneuve and Chalamet, however, commit themselves wholeheartedly to ensuring that the film’s craft not only conveys the reasons and methods, but also convinces the audience to believe in the figure themselves. To this end, Chalamet, though he might prove divisive in this film, is a near-constant surprise—perhaps most astonishingly, he accesses another, resonant, charismatic register of his voice. Every time he hits this register, it feels like the entire cinema could rattle down to pieces with the force of his delivery, further amplified by the fervent passion of his passionately responding followers. It’s an incredibly powerful effect, terrifying even, depending on who you ask.

If there’s anything to be held against this film, it’s that it is such a vast improvement on the first film that it cheapens Part One by comparison. So much of it is already such a staggering technological achievement in its own right, that to realise its dedication to immersion is also serving its ideas of faith and devotion is an experience unlike any other. It’s also harder to glean meaning from its predecessor’s game of Shakespearean political machinations. Villeneuve intuitively understands that the rise of Paul Atreides to the position of Messiah of the known universe is not something for the audience merely to watch, but something to witness and experience in every conceivable way. To this end, Part Two is such a resounding, soul-shakingly powerful success that imagining where Villeneuve’s Dune could go from here presents an unprecedented challenge.

However, it’s worth noting that with a roster as strong as Arrival, Blade Runner 2049, and both Dune films, Villeneuve has already firmly cemented his place in the canon of the greatest science-fiction filmmakers of our era. As Dune: Messiah gradually begins to take shape, we’ve reached a point where Dune has become the most exciting sci-fi film series to reach cinema screens, a previously unimaginable prospect given the formerly unadaptable nature of Herbert’s acclaimed novels.

What comes next? Simple: now that the unadaptable has been adapted, the question becomes how much longer it can be sustained. Now that the already staggering scale of the first part has been surpassed, the question becomes how much further Villeneuve can push the boundaries of what’s possible. And now that Paul Atreides has found his way to becoming the Fremen’s messiah, the question becomes how much longer his reign will be permitted to continue.

USA • CANADA | 2024 | 166 MINUTES | 2.39:1 (THEATRICAL) • 1.43:1 (IMAX GT LASER) | COLOUR • BLACK & WHITE | ENGLISH • CHAKOBSA

director: Denis Villeneuve.

writers: Denis Villeneuve & Jon Spaihts (based on the novel ‘Dune’ by Frank Herbert).

starring: Timothée Chalamet, Zendaya, Rebecca Ferguson, Javier Bardem, Josh Brolin, Austin Butler, Florence Pugh, Dave Bautista, Christopher Walken, Léa Seydoux, Stellan Skarsgård, & Charlotte Rampling.