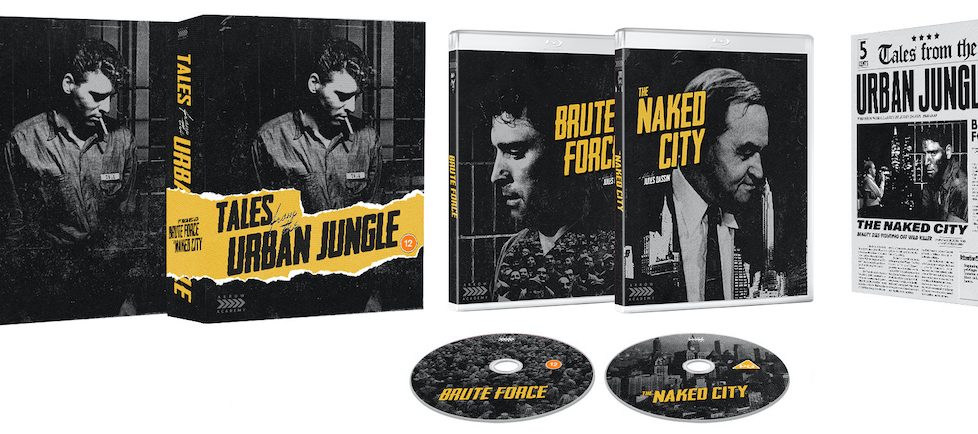

Tales from the Urban Jungle • BRUTE FORCE (1947) | THE NAKED CITY (1948)

A double-bill of film noir classics from Arrow Academy on Blu-ray.

A double-bill of film noir classics from Arrow Academy on Blu-ray.

Arrow Academy upgrade their original 2014 releases of Jules Dassin’s classic film noirs Brute Force (1947) and The Naked City (1948), with new 4K restorations and supplements, for their Tales of the Urban Jungle Blu-ray box-set. Dassin’s reputation rests on a clutch of such Hollywood film noirs and, as well as the two films presented here, his notable achievements include the equally impressive Thieves’ Highway (1949) and, after he found himself under investigation by the House Un-American Activities Committee (HUAC), Night and the City (1950). HUAC investigated private citizens, public employees, and organisations which were allegedly suspected of fascist or communist affiliations. When Dassin was named as a former communist by fellow director Edward Dmytryk at a 1949 hearing, his career in the US was effectively over.

After making Night and the City in London, the exiled Dassin struggled to find projects, with pressure from HUAC, via the American Embassy, often directed at the non-European actors he cast, forcing them not to work on the films he attempted to set up in France and Italy. His post-blacklist European career was finally established with the celebrated French heist drama Rififi (1955), leading to He Who Must Die (1957) and Never On Sunday (1960), both of which were produced in Greece. He also briefly worked again with a major studio, United Artists, to complete the heist caper Topkapi (1964) in Istanbul, with a French, English, American, and Italian crew.

Connecticut-born of immigrant parents, Dassin actually grew up in Harlem, New York City, his family carving out a ghetto existence alongside black, Jewish, Irish, and Italian minorities, “at each other’s throats all the time… divided amongst themselves and taking out their wrath and poverty upon each other.” Radicalised by the theatre of the 1930s, that social milieu later informed the noir films he made in Hollywood. After a high school graduation study tour of European theatres and drama centres, in 1936 he developed his ability to work with actors and honed his skills as a director in ARTEF, The Yiddish Theatre Group of New York.

His political consciousness was awakened after seeing a number of productions at Group Theatre, a left-wing theatre collective formed by Lee Strasberg, Harold Clurman and Cheryl Crawford that would be hugely influential on the formation, in 1947, of the Actors’ Studio and its teaching of method acting. Dassin joined the Communist Party after seeing the Group Theatre production of Clifford Odets’ Waiting for Lefty. However, after being threatened with expulsion from the Party several times over his disagreements with its policy, he withdrew his membership in 1939. His political views would eventually seal his fate with HUAC.

When Dassin began writing for radio and was given his first opportunity to direct on Broadway, Hollywood came calling. RKO Radio Pictures offered him a six-month $200 a week contract “as an observer… allowed to sit and watch the shooting” of Alfred Hitchcock’s romantic comedy Mr & Mrs Smith (1941) and fellow Broadway theatre alumnus Garson Kanin’s Carole Lombard vehicle They Knew What They Wanted (1940). While he admired Hitchcock’s meticulous planning, Dassin was himself averse to it. More impressed with Kanin’s way of creating atmosphere and using actors, Dassin believed instead, together with actors and setting, and “a lot of improvisation… I get the truth of the scene.” After RKO ended the contract, Dassin was unemployed and heading back to New York when, for a reason unknown to himself and his agent, he ended up at MGM. Assumed to be studio chief Louis B. Mayer’s nephew (Dassin had never met him), this misplaced nepotism gained him a try-out as a director. The Tell-Tale Heart (1941), his short film based on the Edgar Allan Poe story, achieved sudden success three months after its completion when it replaced a lost newsreel at a Culver City movie theatre. Dassin had given up on anyone noticing it.

Awarded a seven-year MGM contract, he directed a number of films, starting with spy film Nazi Agent (1941) and followed by a slew of romantic comedies. As Patrick McGilligan noted, he didn’t like talking about his early film career, “especially the period of MGM contract programmers”, the inclusion of which he refused permission for a New York 1995 retrospective. For him, it was a period where “I didn’t know what I was doing and, God forgive me, I didn’t care.” By 1946, with little control over these films and no final cut, he asked Mayer to be released from his contract. Mayer refused and Dassin effectively spent a year on strike and “went nuts.” Asking to meet Mayer again, he suffered a humiliating meeting with other MGM execs and Mayer compared his forcing Dassin conform to his wishes to the example of gelding a favourite race horse. When Dassin rejected this ultimatum, Mayer yelled “Get out of here you dirty Red!” and threw him out of the office. Shortly afterwards, Brute Force would prove that Dassin knew what he was doing.

At a tough penitentiary, prisoner Joe Collins plans to rebel against Captain Munsey, the power-mad chief guard.

Despite his MGM contract being in flux, Dassin’s connection with Brute Force came about because he eventually gravitated to Universal’s more sympathetic independent producer Mark Hellinger, a former columnist who’d gained entry to Hollywood after Warner Bros. hired him to add authenticity to their gangster films. After a fruitful relationship producing A and B pictures for Warners, Hellinger moved to Universal, setting up as an independent producer. At the same time Burt Lancaster’s agent Harold Hecht had a deal with Paramount which allowed Lancaster to make one film a year outside of their contract. In 1946, Lancaster took up a five year option with Hellinger to make one film a year and, after passing a screen test, made his debut in Hellinger’s hugely successful film noir The Killers (1946), based on a Hemingway short story and directed by Robert Siodmak.

Hellinger, keen to get Lancaster into another film, developed Eight Men, a new script by Richard Brooks, the screenwriter of The Killers. Brooks developed this from a short story by Robert Patterson, added his own research conducted at San Quentin penitentiary, as well as his reflections on the recent ‘Battle of Alcatraz’, a failed escape attempt made at San Francisco’s infamous island slammer in May 1946. Hellinger offered the retitled script, Brute Force, to Dassin. According to Dassin, even though he felt dissatisfied with Brute Force —describing it as “a really dumb picture” because the inmates were portrayed as “such nice sweet guys” — he was grateful because Hellinger “let me begin to learn.”

The inmates of cell R17 —Joe Collins (Lancaster), ‘Soldier’ Becker (Howard Duff, making a striking debut), Spencer (John Hoyt), Lister (Whit Bissell), Freshman (Jeff Corey), Kid Coy (Jack Overman) —seem committed to their collective action to escape Westgate penitentiary. However, Dassin gradually reveals the cracks in their united front, with the weaker men influenced by their fear of the sadistic and manipulative Captain Munsey (Hume Cronyn). On his own quest to seize power from the equally weak-willed prison warden, A.J Barnes (Roman Bohnen), and drunk prison doctor Walters (Art Smith), Munsey tunes into and exploits the sense of betrayal each of the cellmates feels for the random sense of justice meted out both by the prison and the outside world.

The cellmates’ sense of betrayal is articulated through a series of flashbacks that attempt, rather unsuccessfully in terms of the film’s characters and structure, to give them all a backstory and simultaneously soften the cynical, bleak edge of the film by showing their relationships with women. Their memories are triggered by a totemic calendar girl picture on the prison cell wall. With its shades of The Shawshank Redemption (1994), the poster allows each briefly to escape the confines of the cell and overtly romanticised flashbacks show how the cellmates became victims of circumstance. We see Joe using crime to pay for the disabled Ruth’s (Ann Blyth) care; Lister’s wife Cora (Ella Raines) leading him to steal from his firm to buy her a new coat; ‘Soldier’ taking the blame after Gina (Yvonne De Carlo) shoots her father for threatening to hand him over to the military police; and Spencer being outsmarted by con woman Flossie (Anita Colby).

It’s a clunky attempt to give a sense of righteousness to their later actions in an already melodramatic film, and one suspects the flashbacks fulfilled Universal’s desire to feature some film noir starlets in what was otherwise a grim, masculine story. However, despite Hellinger wanting to add a feminine dimension to the film, the empathy for these incarcerated men is borne out of a misplaced misogyny that suggests if it wasn’t for these women our ‘heroes’ wouldn’t be in prison. In another flaw, and of little surprise considering the period, the black character Calypso (Sir Lancelot) gets precious little character development, no establishing flashback, and, as his name implies, sings most of his lines in a rather embarrassingly stereotypical way. But he does get one subtle but terrific moment where, with the doctor about to face another dreadful meeting with Muncey, Calypso understandably and discreetly adds more bourbon to Dr Walters’ water. Walters foreshadows the film’s conclusion by telling Munsey: “Not cleverness, not imagination. Just force. Brute force. Force does make leaders. But.. it also destroys them.”

A predominantly masculine film, Brute Force cultivates sympathy for men who, having broken the law because of their own weaknesses, find themselves in an institution and system that desperately requires reform. That failed reform and lack of betterment through education, overseen by the ineffective warden and his alcoholic prison doctor, is also exploited by Munsey. Munsey operates through a distinctly different system of power, by making prisoners capitulate to the repressive forces he has set in motion. As a result, the film contains some very powerful sequences. In one of the most memorable, a stool-pigeon is cornered by fellow inmates wielding blow torches and is forced to his death beneath a steel press in the prison workshop.

Through the stereotype of Munsey, writer Brooks displays what could now be deemed an unpleasant homophobia. Cronyn’s villain is coded visually as homosexual and betrays explicitly fascist tendencies, possibly as a comment, given how society had been turned upside down in the aftermath of World War II, on the growing distrust about anyone who is ‘other’, be they left wing, right wing and/or gay. Munsey’s office walls are dotted with framed pictures of the male physique just above the record player that blares out Wagner (underlining his Nazism, of course). Throughout the film, Cronyn’s performance includes glances at and physical contact with prisoners to imply Munsey’s sadism and authoritarianism is sublimated sexual desire. This plays out in a visceral torture sequence that the censor demanded cuts to, where, stripped down to his vest, Munsey attempts to beat the details of Joe’s escape plan out of convict newspaper reporter Louie Miller (Sam Levene).

Dassin’s response to Brooks’ tangled weave of masculine expression is also highlighted, like Munsey’s physique pics, with beautifully lit beefcake shots of a topless Lancaster and Hoyt. It’s a ‘man’s world’ sensibility that transferred to the film’s publicity campaign with its emphasis on Lancaster’s physique. Lancaster is superb and, with his lithe athleticism and the character’s fatalism intertwined in the film, he moves like liquid through the austere settings created by art director John DeCuir and inventively shot by William Daniels. DeCuir then starting out a career at Universal that would eventually reach its heights with Fox’s epic musicals, The King and I (1956) and South Pacific (1958) sets the tone with his impressive but very claustrophobic studio sets for Westgate, where everything from the cells, workshops and offices to the prison yard, turrets and buildings were all mounted in the studio.

DeCuir’s prison environments deftly sum up the film’s exploration of state sanctioned containment and the fatalistic desire to escape from it. It’s also fascinating to note that DeCuir, entrenched in stylised Hollywood studio production, made an aesthetic leap with Dassin’s next film, The Naked City, one predominantly filmed on and in New York’s actual streets and buildings by cinematographer Daniels, who won an Academy Award for his work. Their efforts on Brute Force climax with the the stylised, studio-bound violent carnage of the failed escape attempt. It’s pretty strong violence for 1947, a factor that the Breen office, who oversaw the Motion Picture Production Code, had complained about from the outset.

Joe and his cellmates attempt to escape during the construction of a drainage pipe. During the escape attempt, the film’s exploration of betrayal is heightened when Joe discovers that one of the gang is a grass. To again emphasise the film’s title, the punishment is brutal. However, the escape attempt descends into chaos and, faced a with a machine gun-toting Munsey, the tension mounts as a wounded Joe struggles to overcome the would-be dictator. In an utterly nihilistic ending, Art Smith’s prison doctor sums up Brute Force’s intent as a political allegory when he turns to the audience and concludes that “nobody escapes, nobody ever really escapes” from such an authoritarian environment.

USA | 1947 | 98 MINUTES | 1.37:1 | BLACK & WHITE | ENGLISH

A step-by-step look at a murder investigation on the streets of New York.

Sadly, The Naked City was producer Mark Hellinger’s last film. He died of a coronary thrombosis three month’s before the film’s release but, arguably, it’s his film and it enshrined his own background as a newspaper columnist, through his own role as the film’s ongoing voiceover narrator, the eye of god observing and commentating above the New York skyline during the opening titles and the film’s unfolding pulp crime narrative. Appropriately, his concluding byline, “There are eight million stories in the naked city. This has been one of them” is spoken over a shot of a street cleaner sweeping up the previous day’s newspapers and their headlines about the film’s murdered model. Hellinger wanted The Naked City‘s police procedural framed as a gossipy, tabloid story about the city streets, the police, murderers, petty criminals and the unfortunates caught up in the middle. The same closing line would be central to the television series of the same name, inspired by the film, that ran between 1958 and 1963.

As a former New York Daily News columnist, Hellinger’s populist style as a writer and producer aligned with a number of other factors in the production of The Naked City. Notably, it coincided with Dassin’s own intent to get out of the studio, move the production to New York and away from the vested interests of Hollywood, which were in decline after a Federal law decreed the studios had to shed their affiliated theatres. While some interiors were created on sound stages as were many process shots, such as those depicting driving sequences, the film is one of the first to primarily use the city for locations, often shot on the streets with hidden cameras in vans and newsstands to retain a sense of verisimilitude. Dassin’s use of a semi-documentary aesthetic to capture his love of the city and his own origins in the Bronx equated with his admiration of Italian neorealism, particularly Rossellini’s Rome, Open City (1945). However, even this verisimilitude was given a helping hand The climactic sequence on the Williamsburg Bridge was remarked upon by co-writer Malvin Wald at a preview screening. He admired the view from the top of the bridge that took in distant tennis courts and tennis players. Wald thought it was “quite a stroke of luck that the tennis players should have been there at the right time”. Dassin simply retorted, “those tennis players were all extras. I put ’em there.”

Co-writers Albert Maltz and Malvin Wald shared Dassin’s intentions. Wald, who’d made documentaries in the film unit of the Forces during WWII, persuaded Hellinger to fund a scouting trip to New York Police Headquarters in an attempt to gather research about police procedures and routines, including visits to the morgue to witness autopsies. It’s this attention to detail and authenticity that Wald used to structure the script, originally titled Homicide, and he later commented:

“No one had done a film where the real hero was a hard-working police detective, like the ones I knew in Brooklyn. We knew we were making a new genre that became the police procedural.”

By that mark and with its use of authentic locations, The Naked City can be seen as a hugely influential film. It was re-named The Naked City to acknowledge the inspiration of celebrated tabloid photographer Arthur Fellig’s pioneering book of the same name that depicted graphic crime scene images. Published under the pseudonym Weegee, phonetically akin to the spirit board ‘Ouija’ after Fellig’s uncanny ability to sniff out such crimes before anyone else, allegedly Hellinger made him the film’s still photographer to cannily avoid having to buy the book’s title.

Hellinger was unconvinced by Wald’s documentary style script and Dassin turned to his friend Alfred Maltz to reinvigorate and save the project. Maltz, a novelist, former Warner Bros. contract writer and Academy Award winner for his Pride of the Marines (1945) script, was in tune with Dassin’s social and political vision for the film, having shared a similar experience growing up in New York. He and Dassin carefully balanced the script’s polemics, documentary realism and populist cinema. A former Communist party member, Maltz was also investigated by HUAC and asked to testify as one of ‘The Hollywood Ten’ just after finishing the revised script for The Naked City. Refusing to name names, he was convicted of contempt and was in prison, serving a ten-month sentence, when the film came out in March 1948.

The film literally descends from the heavens, comes down to earth at street level and, as day passes into night, Dassin focuses on the scene of the crime, deep within the city streets. A former model, Jean Dexter, is attacked in her Upper East Side apartment bedroom by Willie Garzah (Ted De Corsia) and Peter Backalis (Walter Burke) and is drowned in her bath tub. Dassin follows Detective Dan Muldoon, (Barry Fitzgerald) and his young novice cop colleague Jimmy Halloran (Don Taylor), as they trail the killers and beneath the false glamour, discover Jean’s dubious morals and the corrupt natures of Jean’s associates.

Dassin’s step-by-step urban police procedural unfolds on the city streets, tenements, piers and bridges of New York, and the main characters slowly reveal all the duplicity and betrayal, one of the director’s key themes in his film noirs, that culminated in Jean’s murder. A key figure is her former boyfriend Frank Niles (an excellent Howard Duff returning from Brute Force) and, as the habitually lying playboy, at the heart of futile leads, abortive questioning and unproved incrimination, he is the supreme symbol of duplicity in the film. What’s also striking is the sense that these crimes are part of the everyday fabric of New York and it takes Muldoon and Halloran’s determination and patience to unpick that frayed cloth and find the murderer, using a combination of world-weary experience and naive enthusiasm. They fulfill Wald’s then novel idea that “the Police Department, with all its fingerprint experts, crime scene photographers and autopsy physicians, solved murders, not Sam Spade-type private eyes working alone.”

While Fitzgerald and Taylor are perhaps the weakest performers (by dint of Fitzgerald’s character coming across as too gentle for a grizzled detective, and of Taylor lacking acting experience), through the two detectives the old roots of the city meet modern, semi-detached suburbia. Crime and punishment inside and outside of the city are reflected in Halloran’s weakness when it comes to correcting his errant young son at home and then in the heartbreaking scene where Muldoon talks to Jean’s mother. She initially rejects her wayward daughter, “so crazy to be with the bright lights. No bright lights for her now”, as a symbol of the American Dream turned sour but then faces the chilling reality of identifying her ‘baby’ in the morgue. Dassin revels in building the tension through various interrogations and street-level pursuits to the grand finale, where Jimmy tracks down Willie in his tenement hideout after he has already disposed of his murderous accomplice Backalis. Once again, even though there are female characters central to the film, Dassin returns briefly to a focus on questions of masculinity, contrasting the rookie cop, intellectually adept but physically weaker, with the sweating, muscular torso of the former wrestler, a fugitive burning with an overpowering endurance that is only extinguished in the gripping climax atop the Williamsburg Bridge.

As Gordon Gow noted, The Naked City’s “actuality-look impressed itself upon the spectator, in marked contrast to the studio-lit romanticism” of its noir contemporaries and, through its locations and cinematography, overruled some of Dassin’s instincts to use “heightened realism for such a plot.” It was a different approach rather than a better one. However, when Dassin brought the film back, he recalled “the executives were horrified. They didn’t want to release it. They wanted to take all the shots of New York out and put them in their stock library and kill the rest. I fought like hell with them.” Although he had been promised by Hellinger that his version of the film would remain intact, according to Dassin it was modified to remove ‘Red’ concerns after Hellinger’s death. Dassin felt the film had been compromised and he later recalled the removal of two sequences showing some of the squalor on the streets, a reminder of the New York background from which he had emerged.

USA | 1948 | 96 MINUTES | 1.37:1 | BLACK & WHITE | ENGLISH

director: Jules Dassin.

writers: Richard Brooks (story by Robert Patterson) (Brute Force) • Albert Maltz & Malvin Wald (story by Malvin Ward) (The Naked City).

starring: Burt Lancaster, Hume Cronyn, Charles Bickford, Yvonne De Carlo, Ann Blyth, Ella Raines, Anita Colby, Sam Levene, Jeff Corey, John Hoyt & Roman Bohnen (Brute Force) • Barry Fitzgerald, Howard Duff, Dorothy Hart, Don Taylor, Frank Conroy, Ted de Corsia, House Jameson, Anne Sargent, Adelaide Klein & Tom Pedi (The Naked City).

I am indebted to the following sources: Douglass K. Daniel, Tough as Nails: The Life and Films of Richard Brooks, (University of Wisconsin Press, 2011) • Dan Georgakas and Petros Anastasopoulos, ‘A Dream of Passion’ Dassin interview, Cineaste (Vol. 11/№1, Fall 1978) • Gordon Gow, ‘Style and Instinct’ Dassin interview, Films and Filming, (Vol. 16/№4, February 1970) • Tom Gunning, ‘Invisible Cities, Visible Cinema: ‘Illuminating Shadows in Late Film Noir’, in Jeffrey Geiger and Karen Littau, Cinematicity in Media History, (Edinburgh University Press, 2013) • Dennis Hevesi, ‘Malvin Wald, Creator of ‘Naked City,’ Dies at 90’, The New York Times, (11 March, 2008) • Patrick McGilligan, ‘I’ll Always Be An American’ Dassin interview, Film Comment (Vol. 32/№6 November 1996) • Rebecca Prime, ‘Cloaked in Compromise: Jules Dassin’s “Naked” City’, in Peter Stanfield, Frank Krutnik, Steve Neale, and Brian Neve (eds.), Un-American Hollywood: Politics and Film in the Blacklist Era, (Rutgers University Press, 2007) • Tim Pulleine, ‘Jules Dassin obituary’, The Guardian, (02 April, 2008) • Peter Shelley, Jules Dassin, The Life and Films, (McFarland, 2011)