ARREBATO (1979)

A low-budget horror filmmaker gets in touch with an eccentric who's trying to film his consciousness during drug abuse.

A low-budget horror filmmaker gets in touch with an eccentric who's trying to film his consciousness during drug abuse.

When talking about ‘love letters to cinema’, we rarely apply the term to films like Arrebato / Rapture. But why? It isn’t a maudlin work, but unlike those claimed love letters, it also doesn’t intend to stir up the dust of a distant magic from long ago. Nor does it rekindle any of the sort of purity or insouciance that comes with a first cinematic love like those films do. It is instead ugly, uncomfortable, obsessive, and exhausted, as if from a lifetime devoted to a medium that can’t love you back. But like those other love letters, it shares the received wisdom that one can be consumed entirely by their master passion, positively or negatively.

Arrebato is such a twisted love letter to the cinematic drug that, on the surface, it doesn’t even appear to be a love letter at all… it’s more a suicide note. The characters are already in a state of living death, petrified like mosquitos in amber by sex, drugs, and celluloid.

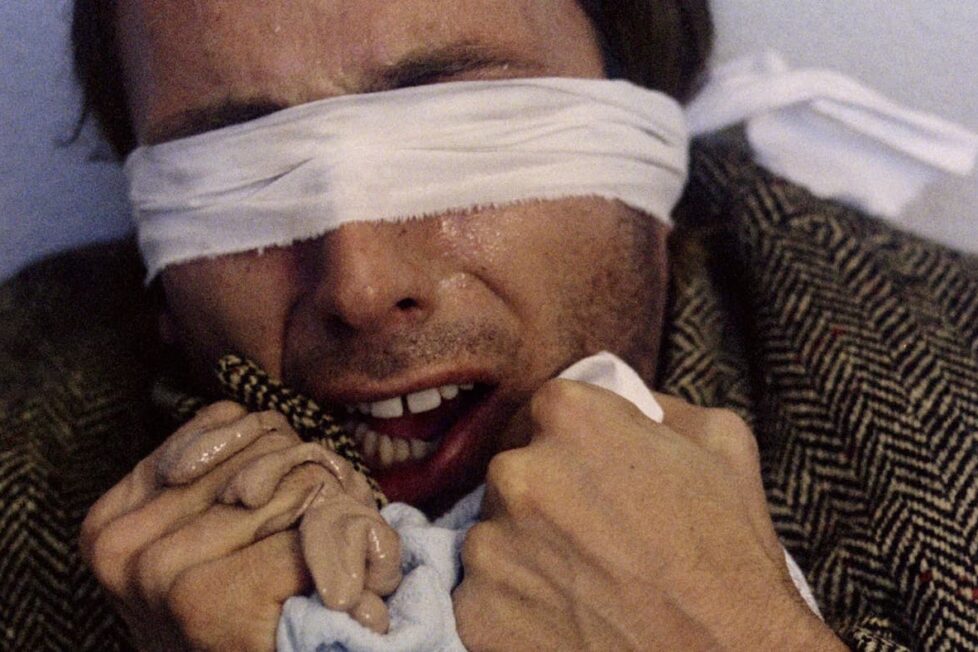

José (Eusebio Poncela) is a director as addicted to the moving image as he is to heroin. He’s in the editing stages of a feature length film, a cheapo horror as junky as the stuff he injects into his veins—in extreme closeup, it should be noted, as director Ivan Zulueta rarely shies away from a chance for physically jarring images. José also remembers the good old days, when their work meant something. His girlfriend, Ana (Cecilia Roth), makes fun of the film, claiming horrors are always “the something of something” (the return of this, the revenge of that).

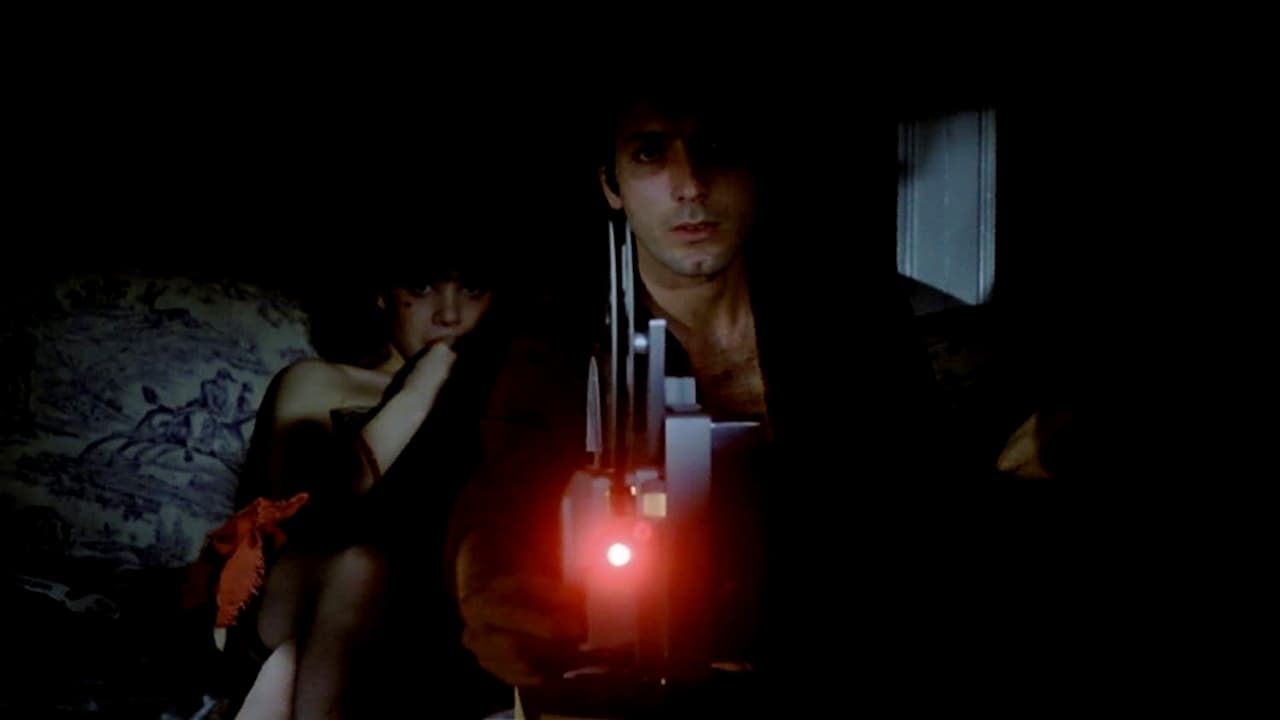

José still deliberates carefully over shot lengths and timings of cuts, because artists know it isn’t what you’re working on, it’s how you work on it. Only now it’s the films that are working on him, picking apart his precarious stability, threatening to throw him into the void. It isn’t long before a film sends him tumbling into it headfirst. He receives a film reel in the post from Pedro (Will More), a sickly, petulant experimental filmmaker with whom he’d had a couple of encounters. In his apartment, José pushes aside the stifling detritus to set up the film.

There are record players, ties and spoons, television sets—always some form of stimulant is running and we’re never granted the luxury of quietude. Ivan Zulueta and cinematographer Angel Luis Fernandez keep us hemmed in this miserable little flat, paying careful attention to the mechanisms of José’s life. The preparing of his ‘powders’, the clunking of buttons pressed, the film reel slowly unspooling… it’s as exciting and satisfying as it is suffocating. Pedro’s whispered narration tells José this may be the last thing he ever receives from him. The narration carries on through the film, paranoid, rambling and impossible to get out from under your skin.

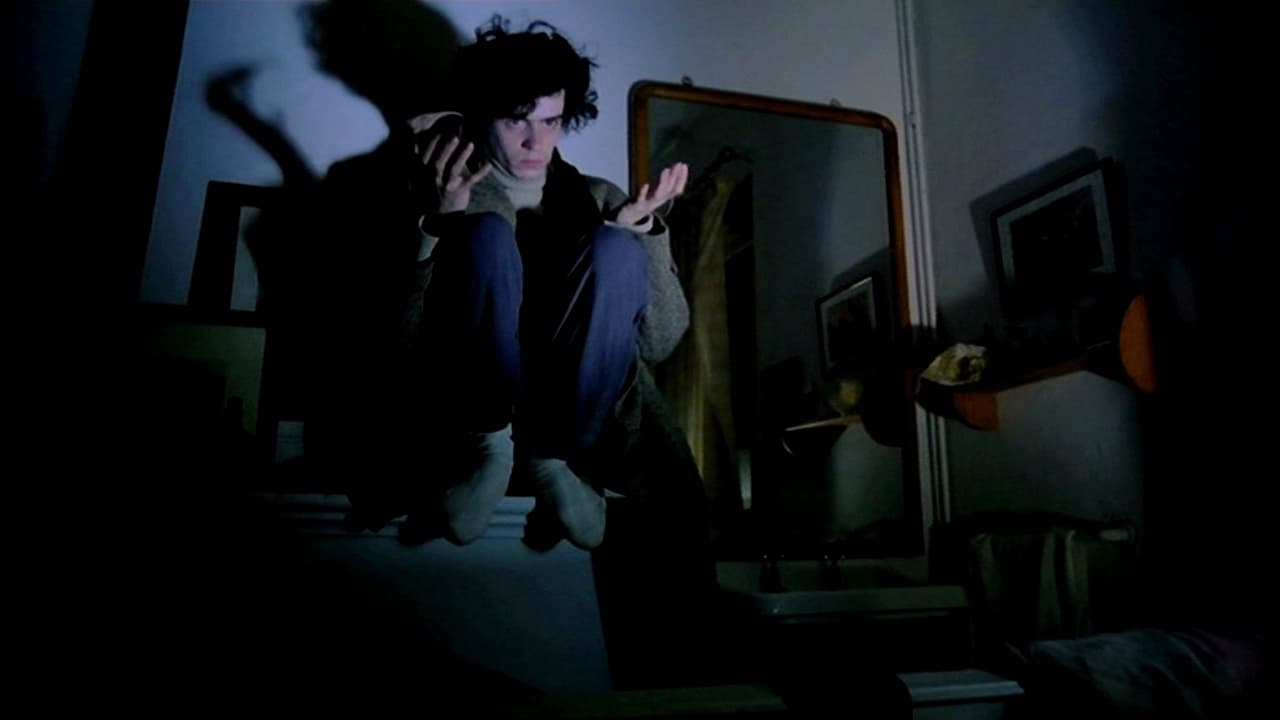

But José had been thinking of Pedro even before he set up his film. In startling moments, Pedro’s likeness flashes momentarily in José’s bathroom; a fantastically confounding moment of editing that mimics the delusions of an increasingly unsteady mind. José throws himself fully clothed back into the overrunning bathtub at this, as if to drown this spectre. Similarly jarring are harsh cuts to low-resolution footage of a vicious car accident. Are these dreams? Are they things that Pedro has filmed? Is there much of a difference?

When we finally see Pedro, it’s in the form of two long flashbacks which José remembers after Pedro alludes to them in his films. If José is troubled then José is something far, far worse. He wears duffel coats in the hot Spanish summer, he plays with children’s toys, and screams and sobs at all hours at his own short films. When José and his then-girlfriend Marta (Marta Fernandez Muro) meet him in this first flashback, they’re scouting for locations and the large country house he lives in seems ideal. But the trip becomes entirely about Pedro. Is this just a deeply spoiled, coddled kid who has been given the freedom for his egotism to grow? Or is he genuinely sick?

His films don’t give much of an answer. They show sped up images of shadows passing across grass, and later, are fast-forward travelogues of the US. These are interspersed with the film itself, and take on quite a beautiful meaning when positioned that way. It’s only when we meet the director and hear him talk that we realize there is something far darker happening to him. The films can’t possibly encompass it.

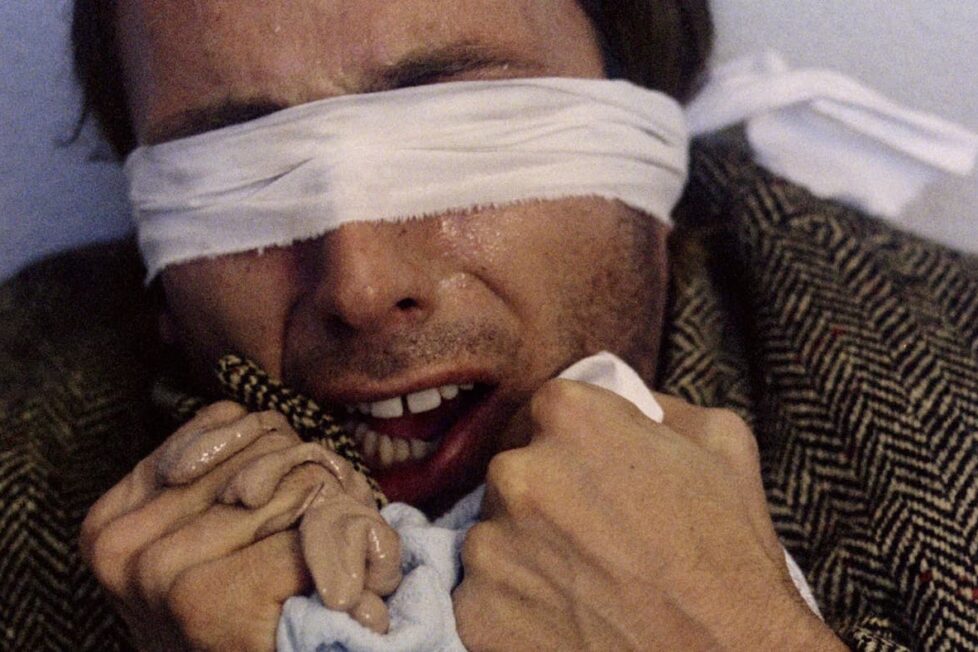

He constantly holds something like silly putty in his hands, only far gooier. It sticks and, one would imagine, reeks of hand sweat. He looks as if you might get stuck to him if you get too close, which explains why José appears to be stuck in his memories of Pedro. They snort cocaine together and Pedro talks of speeding up and slowing down time, looking for hidden rhythms in his films that have yet to be discovered. Like films, the goo he plays with has a malleability—it can be balled up or stretched out but it usually goes back to it’s original form. Perhaps this is why he’s so ill; he can never seem to fully transcend.

José’s relationship with him grows increasingly knotty. They read film magazines together, and a quiet air of sexual tension simmers underneath. Zulueta makes something feel forbidden, whatever that might be, as if these people, by taking enough drugs, are edging towards a door to a discovery. It brings to mind the final film within Irma Vep (1996), as if by merging life and film, Pedro might make something so communicative and dazzling that it doesn’t need to say a word. Are Pedro and José a sort of Bonnie and Clyde? Will they die for what they love?

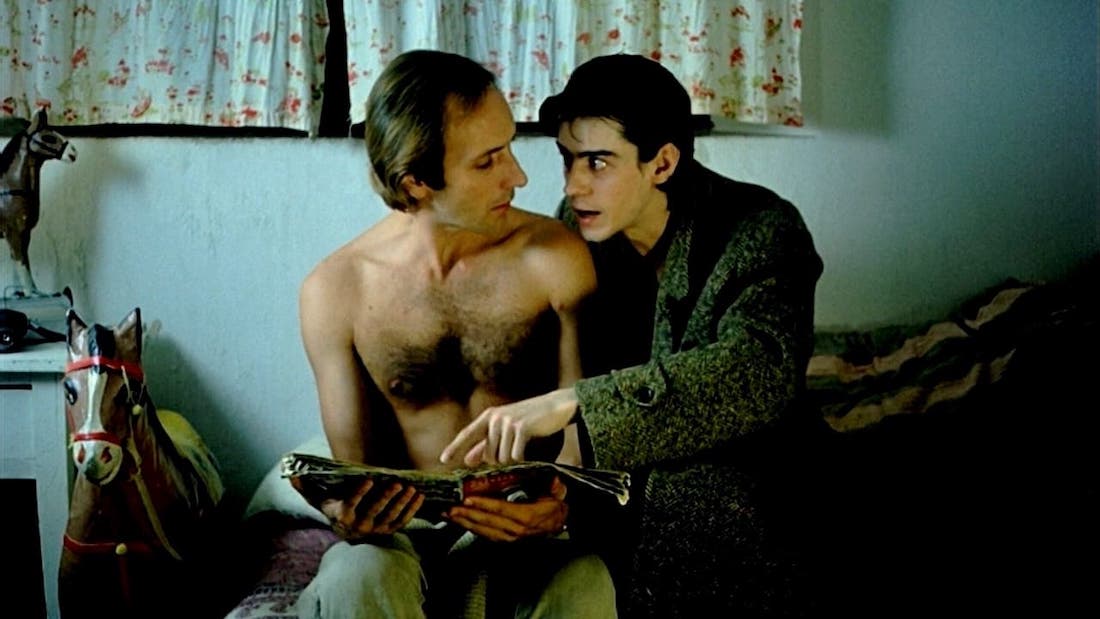

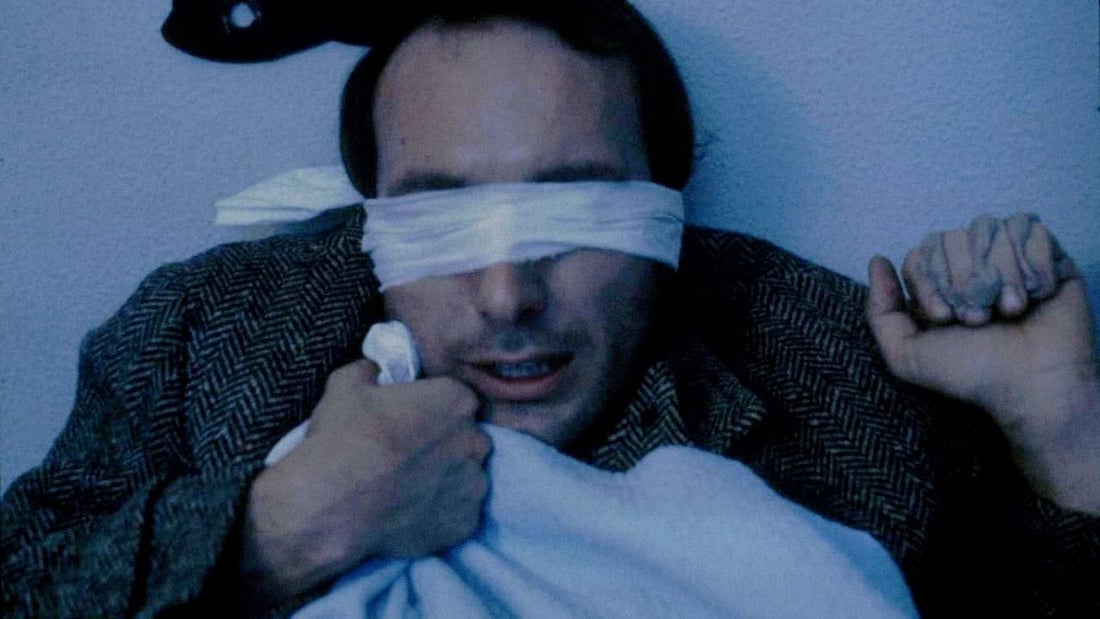

We begin to spend more time with Pedro, which is when Zulueta really lets us into the monomania at play. Pedro tells José through the film that he has begun filming himself sleep. His work is getting more experimental, homemade and insular. No longer is he seeming to make film art, but instead is testing his own mind. Every day he obsessively watches back the footage of himself sleeping, running to the camera shop to have the images developed. There he sees something that he becomes instantly enamoured with—a frame of pure red appearing inexplicably in the middle of the night’s filming.

For most, this would be acknowledged as a flaw in the film stock, a simple glitch. But to a compulsive, artistic mind, it has to mean more. And therein lies one of the many tragedies of Arrebato; the constant and futile search for something more, and the refusal of others to believe it. The sickly, pale Pedro soon becomes pitiable, someone who has truly been fused with his obsession, to the point that he now is becoming the art. Is this something José could ever achieve? Perhaps not, and perhaps that’s where their tension stems from. He can make the same films over and over, while, for all his madness, Pedro is trying to find away forward in the dark.

And at this point, the film begins to resemble a possession film, the kind that Pedro might even sneer at. Like George A, Romero’s superb Martin (1977), we’re attempting to follow someone who’s already half-way out the door and given in to their delusions. It’s disturbing and heartbreaking, and there seems to be genuine concern for the kind of isolationism that occurs with mental illness. An addiction parallel can also be read into; the ‘powders’, as he calls them, can slow down or speed up time, whilst for José they only slow him down. Film itself is an addiction for these men, and as Arrebato itself seems to fast-forward at certain points, we soon realise there are no walls between its ideas, no line between fiction and reality, film and drugs.

Things begin to crumble further. More red stills begin to appear in Pedro’s film, and he believes that soon, it will engulf him entirely. That he will disappear into the film. People caught in Arrebato’s strange editing rhythm’s have disappeared before our eyes, and like the impossible reality of Lost Highway (1997) we begin to lose track of what reality actually is. Is it something we see, or something that’s filmed?

But perhaps this is what Pedro wants, and it’s also what many directors are after. After all, if you can attempt a rapture rather than something less, then why wouldn’t you? Isn’t the pursuit of all art madness in its own sense, trying to attain the unattainable? It’s then a remarkable achievement that Arrebato does indeed feel like a rapture.

It isn’t a film to be understood or compartmentalised, instead it is a complete rupture of the things that make up a film, all of them bleeding into one acrid puddle of melted plastic and celluloid. To watch Arrebato is to give yourself over to a film entirely, and as such it requires a kind of surrender. It’s all too rare that a film possesses its audience in the truest sense, but Zulueta achieved that here with a work that demands you give into its strange movements and disturbing digressions. It can feel like entering the mind of a deeply unstable person, but then, what should cinema be for if not for new experiences? 44 years on and Arrebato feels new and dangerous, a seeming contorted love letter, a goodbye, and fuck-you to a cinema that so rarely allows us to be raptured.

SPAIN | 1979 | 105 MINUTES | 1.66:1 | COLOUR | SPANISH

This new release from Radiance is a must-own Blu-ray. They’re a new label but their output has been incredibly good and reliable (Welcome to the Dollhouse being my personal favourite so far). This is an excellent 4K restoration, with the film looking crisp and colourful whilst maintaining that gorgeous, low-budget grain. The soundtrack is get-under-your-skin good, and sounds full and carefully mastered in this version.

The extras are also well worth the asking price, particularly the hour-long deep dive into the making of the film. After the trip that is Arrebato, this documentary is absolutely essential to begin finding your footing once again, and provides a great deal of context for what went into making the film.

writer & director: Iván Zulueta.

starring: Eusebio Poncela, Cecilia Roth, Will More, Helena Fernan-Gomez & Marta Fernandez Muro.