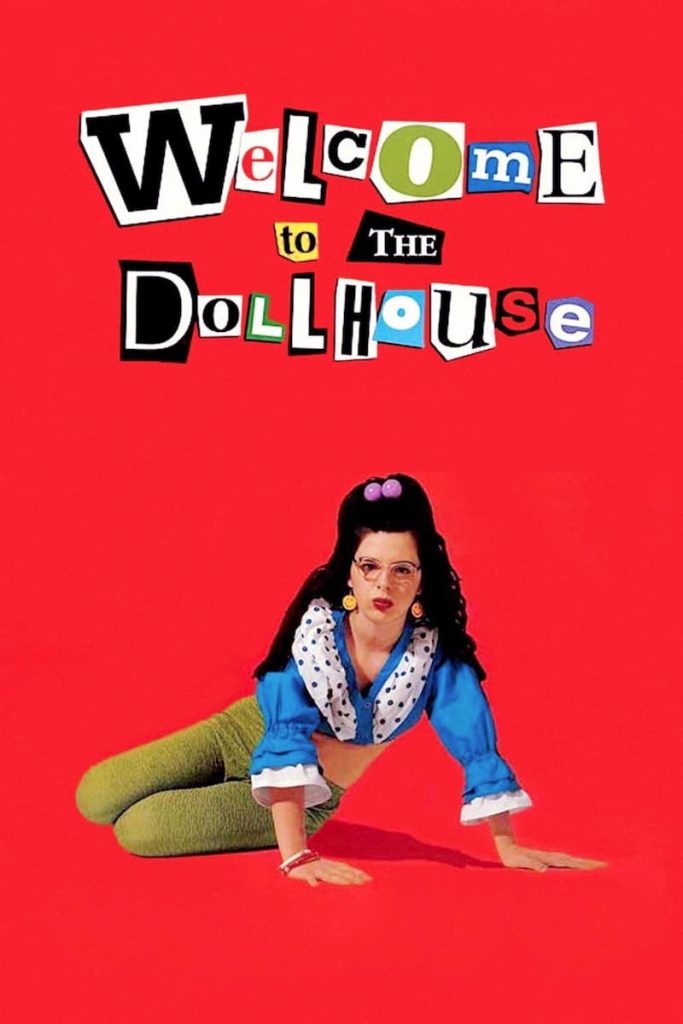

WELCOME TO THE DOLLHOUSE (1995)

An awkward pre-teen struggles to cope with inattentive parents, snobbish classmates, a smart older brother, an attractive younger sister, and her own insecurities.

An awkward pre-teen struggles to cope with inattentive parents, snobbish classmates, a smart older brother, an attractive younger sister, and her own insecurities.

“Why do you hate me?” 11-year-old Dawn asks a girl who’s tormenting her. “Because you’re ugly.” Sad, touching, but also agonisingly funny, Todd Solondz’s Welcome to the Dollhouse is totally accurate about the viciousness with which children can treat one another, often as they struggle in learning how to love. Never lecturing the viewer, nor excessively solemn, it still pulls no punches.

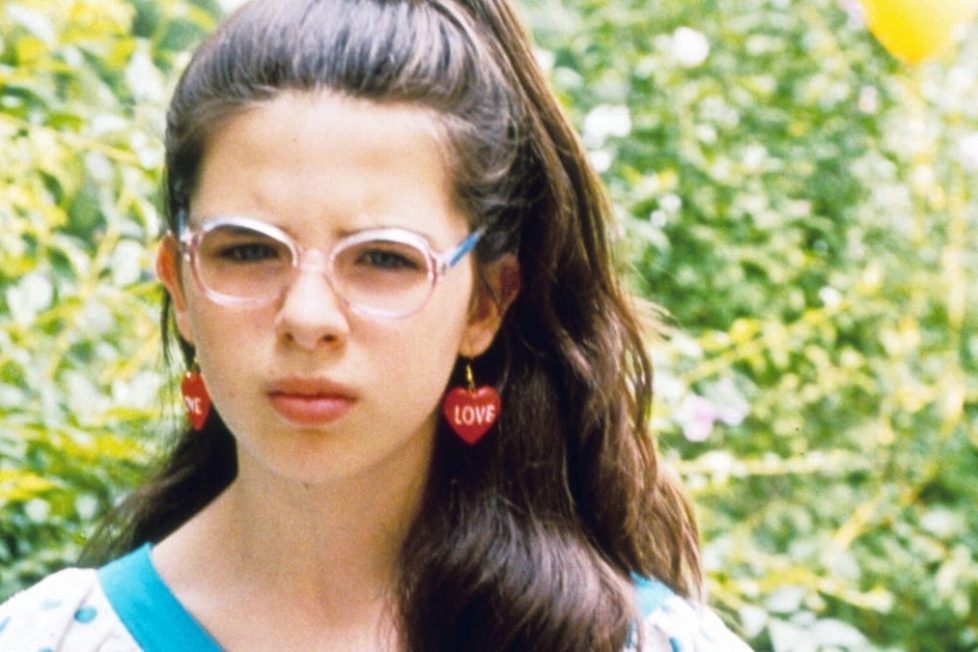

The humiliations dished out to its central character Dawn (Heather Matarazzo) by her schoolmates are frighteningly believable; reminders of the kind of casual pre-teen nastiness most adults have managed to forget. And while sometimes the brutality is comic (there’s a brief and priceless scene where Dawn’s sawing off the head of her little sister’s mermaid Barbi), it can also be genuinely dark. A little later, as that sister sleeps, Dawn’s standing over her, holding a hammer and wondering if she dares…

Dawn is an outcast at her junior high school and even at home, where her parents, or at least her mother (Angela Pietropinto), treat her as an ugly duckling in comparison to her nerdish brother Mark (Matthew Faber, looking startlingly like a young Bill Gates) and her smugly cute, ballet-obsessed younger sister (Daria Kalinina). Her only real friend is a slightly younger boy, Ralphy (Dimitri DeFresco), who is himself a victim of bullies, while her nemesis is self-consciously tough kid Brandon (Brendan Sexton III), who torments her in class and out.

Perhaps inevitably but still surprisingly, an odd kind of romance slowly develops between Dawn and Brandon, who (despite his wonderfully evil face) turns out to be as lonely as Dawn in his own way. Dawn, however, is slow to realise this, harbouring instead some completely unrealistic hopes of ending up with hunky Steve (Eric Mabius), an older boy who plays in her brother’s out-of-tune garage band The Quadratics. And she also manages, as kids clumsily navigating relationships will, to alienate Ralphy.

By the end of the movie, not much has really changed from the beginning: Dawn is still alone, things not having worked out with either Brandon or Steve (for different reasons), and she doesn’t seem particularly happy as a bus trundles her to Walt Disney World with her schoolmates in the final scene.

Welcome to the Dollhouse isn’t the kind of coming-of-age movie where the main character learns important lessons about life and matures as a result. At the close Dawn remains an outsider, still seemingly has a rather bad attitude herself. Indeed, despite the intrigues of the Brandon and Steve relationships and one melodramatic incident with Dawn’s annoying sister Missie, it’s not really a movie with a plot or much character development. Instead, it’s a portrait of life in a kids’ world. Adults rarely appear and, when they do, they’re almost invariably threatening—or at least annoying.

As a portrait, it’s a film where the performances and mise en scène are every bit as important as the narrative. And they’re consistently great. Matarazzo (only a little older than her character ) makes a terrific Dawn, capturing the awkwardness of the time between childhood and full-blown teendom. She doesn’t realise how naive she is. She might believe she’s mature, but she doesn’t really understand the world of older kids, let alone that of adults. She still has a Garfield poster in her locker (the only graffiti-strewn one in the school, it seems) whereas Brandon has a topless pin-up.

Matarazzo conveys all this with magnificent subtlety; her face barely mobed from one mood to another, yet somehow communicated such a wide range of emotions (anger, bemusement, nervousness, humiliation) through almost identical expressions. Sexton, though not as present on-screen, has an equally difficult role requiring him to slowly reveal his vulnerabilities without becoming too nice or losing a sense of frustrated menace.

Among the adults, Pietropinto’s bird-like and highly-strung mother, all huge lips and teeth, is perhaps the stand-out, but Bill Buell’s quieter, perpetually vexed dad compliments her well, and Rica Martens’s ill-tempered schoolteacher contributes convincingly to Dawn’s travails. The production design and costumes, meanwhile, are a delight. It’s set in the mid-1980s (Solondz started writing it around 1989), and anyone familiar with that era will be both charmed by the wealth of accurate detail and amused by its slight exaggeration. Floral shirts abound, and the TV room at Dawn’s home, decorated entirely in shades of brown and orange, is particularly marvellous.

Above all else, though, it’s Welcome to the Dollhouse’s unusually perceptive portrayal of its youngsters that makes it such an absorbing movie. “I couldn’t think of any American films that dealt in any serious way with childhood,” Solondz has said. “Children in American films were either cute like a little doll or evil demons.” He manages in this film to entirely avoid those stereotypes; although the original script was darker, in the version produced none of the kids is really bad, yet none of them is entirely likeable either.

They’re quick to pick on any slight departure from the norm, but underneath they’re not really all that different; even Brandon and Dawn, superficially as unlike each other as two people could be, are both victims of others’ prejudices, reacting aggressively to exclusion from the social mainstream. And the cruelty with which the kids treat one another doesn’t seem to come from deep within; it’s more like some kind of irresistible infectious disease that periodically afflicts them all. Brandon mouths “fuck you” at Dawn repeatedly, and soon she is doing it to her sister.

So, while Welcome to the Dollhouse is certainly not offering a rose-tinted view of childhood, nor is it a hopelessly bleak one in the manner of Larry Clark’s Kids (1995) from the same year. In other words, it’s emotionally realistic even in its more far-fetched moments—a point recognised by many critics and the Sundance festival, where it won the ‘Grand Jury Prize – Dramatic’ in 1996. The New York Times said it “brings new insight to name-calling and many other pre-adolescent agonies”, and praised its “wrenching emotional acuity beneath a veneer of devilishly funny surface details”. Roger Ebert, who loved the movie, observed it “shows the kind of unrelenting attention to detail that is the key to satire.”

The character of Dawn appears in two further Solondz films, although they aren’t strictly speaking sequels, and indeed contradict each other in their account of her subsequent life. In Wiener-Dog (2016), its title also referring to her nickname in Welcome to the Dollhouse, she’s played as an adult by Greta Gerwig, while Kieran Culkin portrays the grown-up Brandon; yet in Palindromes (2004) she is already dead before the movie begins, though her parents and brother are seen at her funeral.

Matarazzo went on to have a long career, as did Sexton, even if neither could be called a star today. The biggest beneficiary of Welcome to the Dollhouse’s success has been Solondz himself. Dollhouse and his next film, Happiness (1998), are probably still his best-known works, but he remains a critically acclaimed writer-director and the qualities with which he infuses Dollhouse are easy to see.

It’s not a flashy movie (for example, the photography is hardly noticeable, so absorbing are the characters and the minutiae of their surroundings), but it’s perfectly-crafted and not a moment is wasted. And most of all, it’s consistently smart and original, with a wry style disguising sharp observations about the real lives of kids.

USA | 1995 | 88 MINUTES | 1.85:1 | COLOUR | ENGLISH

writer & director: Todd Solondz.

starring: Heather Matarazzo, Brendan Sexton III, Eric Mabius & Matthew Faber.