THE MAN ON THE ROOF (1976)

In 1970s Stockholm, the murder of a detective exposes brutality within the police department.

In 1970s Stockholm, the murder of a detective exposes brutality within the police department.

In the extras of Radiance Film’s new re-release of Bo Widerberg’s The Man on the Roof / Mannen på Taket, the writer-director describes the film as being “action, action, plus the discussion.” And certainly, it could seem a departure into less demanding, crowd-pleasing territory for the maker of movies like the tragic Elvira Madigan (1967) and the organised-labour drama Ådalen 31 (1969). Yet Widerberg, a critic as well as a thoughtful and serious filmmaker, very much has a point to make too; while The Man on the Roof might feel, at first glance, like nothing more than a rather sombre police procedural that becomes a siege thriller, he also intended it as a film about police malfeasance and the way that oppression and mistreatment in society aren’t always visible until the oppressed strike back. The notional “bad guy” here, thus, is very much a victim too.

This might have been clear enough to a radically-minded viewer in the mid-1970s. Today, it has to be said, the film’s more serious side isn’t so immediately apparent (at least without Widerberg telling you it’s there). The message about police brutality comes across clearly enough, but still, because all the obviously sympathetic characters as well as the less sympathetic ones are police officers—indeed, nearly every character of significance is—it’s equally easy to see it as broadly pro-police.

If The Man on the Roof doesn’t quite succeed in conveying its agenda, though, it remains a gripping, well-acted, and unusually realistic police drama with strong sense of time and place. Widerberg was heavily influenced by cinema verité as well as the French New Wave.

The movie opens with a man in dark shadow at a table in a room, the frame as static as a painting. He appears to prepare something, then leaves, goes to his car, and drives through the night. We still don’t see his face. Widerberg then cuts to another man lying in a hospital bed, also almost immobile. The corridor outside is still, too, apart from a nurse. There’s a powerful sense of quiet and stasis but also of something about to erupt—and soon enough it does, in a jolting sequence where the man on the bed notices an eye peering through the curtains from outside into the room, and then a sudden knife appears before the screen explodes in blood. It’s all very quick, but it makes an important point: beneath the apparently calm surface of society, violence may be waiting to burst forth.

The murdered man, we learn, was police lieutenant Stig Nyman (Hadar Johansson), and we start to meet the other members of the Stockholm police department who will investigate his killing. Most prominent among them is Inspector Beck (Carl-Gustaf Lindstedt; Man on the Roof is based on the novel The Abominable Man / Den Vedervärdige Mannen från Säffle by Maj Sjöwall and Per Wahlöö, who also featured the Beck character in several other works of crime fiction). He’s joined by another middle-aged investigator, Rönn (Håkan Serner), and also by two younger men, Kollberg (Sven Wollter)—who is first seen at home changing his baby–and Larsson (Thomas Hellberg).

Among those they question are a less likeable, possibly abusive, maybe even fascist—certainly uniform-loving—officer who worked with the victim, Hult (Carl-Axel Heiknert). And then there are several other police characters less fully developed, all of them unglamorous, most of them ordinary-looking and tired. Indeed, there’s an air of great weariness throughout the first half of the film. Bilious green colours are prominent, perhaps suggesting corruption as well as the unpleasant nature of these men’s jobs; spaces feel oppressive, one can almost sense the heaviness of the walls that enclose the characters, and long-held shots amplify the effect.

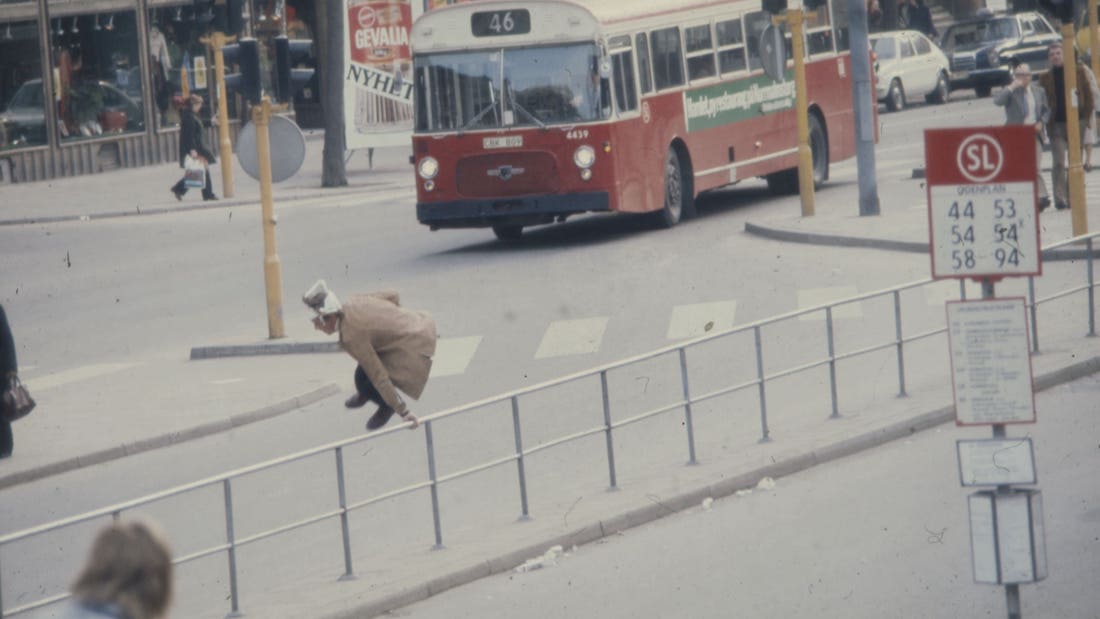

Around halfway through, however, Man on the Roof suddenly switches genres, turning from a jaded procedural into a sniper/siege movie. (No spoilers here, as the title and Blu-ray menu artwork give it away). Now it’s more kinetic and more dynamic, with many more exteriors (Stockholm locations) in contrast to the overwhelming interiors of the first half.

There is carnage and destruction, there are aerial shots, and even a body swinging from a helicopter. The film starts to show much more interest in physical practicalities (Widerberg’s verité influence coming through), there are well-set-up scenes of suspense. For example, where a little boy with a tricycle seems to come into the sniper’s range, and the score by Björn J:son Lindh takes on a sense of uneasy urgency (as well as a slightly Indian flavour). But there’s also a sense of helplessness that echoes the first half of the movie, and may have had especial resonance for viewers in the mid-’70s when hijackings and terrorism in general were so much in the news.

Kollberg and Larson now come to the fore as characters, to some extent replacing Beck and Rönn, who had dominated the first half. But still the shooter, the man we saw in darkness in the first shot, isn’t shown to us. He, of course, is the victim whose plight Widerberg intends to highlight, the man pushed toward committing crime himself because it was committed against him, and though we won’t see his face until the very end, we learn much more about him. His humanity is even underlined by a throwaway shot of a cup of coffee that he’s taken to his rooftop perch, precisely recalling another cup of coffee that the policeman Beck was offered earlier while watching the crime scene.

Though Man on the Roof is at heart about this victim-turned-killer character, Eriksson (Ingvar Hirdwall), it’s the detective Beck who dominates, and Lindstedt—though primarily a comic actor—is first-rate in the role. He’s a bit shorter-tempered and less withdrawn than Serner as his colleague Rönn, a more precise and methodical man who relies much less on inspiration; Rönn (given the highly inappropriate middle name of Valentino, one of a few crazy-humour touches in the film) refers to facts in his notebook while Beck speculates. They make a great odd couple.

Also notable in the cast are Gus Dahlström as the father of the shooter, nervous about the situation into which he’s been plunged but also adamant in support of his son; Hellberg as the slightly flamboyant detective Larsson, a little reminiscent of Peter O’Toole; and Heiknert as Hult, who at first seems thoroughly repulsive but holds some surprises.

There are plenty of moments where The Man on the Roof is thought-provoking. For example, an exchange where a young civilian man who has helped the police try to resolve the sniper situation is told off for a minor infraction (rather than thanked) is a telling one, especially since the officers have already said they’re not concerned by the same infraction committed by the shooter Eriksson himself; there is one law for law enforcement, it seems, and one for everyone else. But the film would benefit from more of these, to more clearly illustrate its argument, and for much of the time it doesn’t quite achieve what it sets out to do.

Issues such as police violence and the closing of ranks against criticism remain relevant today, but The Man on the Roof’s almost complete reliance on police characters muddles the point—it’s perfectly easy to interpret the film as saying that the police are basically good, and that only a few bad apples are to blame for any problems.

Similarly, while keeping Eriksson off-screen for nearly the entire movie has some dramatic impact, it also encourages us to forget that he is a human being rather than a faceless threat; his motivation is critical to Widerberg’s message but it runs the risk of seeming an abstract, academic point rather than a raw emotional one. And opting, eventually, to resolve the film (with its oddly sudden ending) through the trope of heroic solo cops rather than a more realistic collective operation also encourages us to root for them, rather than Eriksson.

Still, even if the message that Widerberg intended to deliver is obscured by the way that the story and presentation so often suggest the opposite, purely as a police thriller it’s an engrossing and frequently surprising film with many realistic characters and a vivid sense of Stockholm in the 1970s.

SWEDEN | 1976 | 112 MINUTES | 1.66:1 | COLOUR | SWEDISH

director: Bo Widerberg.

writer: Bo Widerberg (based on the novel The Abominable Man by Maj Sjöwall and Per Wahlöö).

starring: Carl-Gustaf Lindstedt, Sven Wollter, Thomas Hellberg & Håkan Serner.