Agatha Christie 4-Film Collection (1974-1982)

Essential viewing for any fan of Agatha Christie, this lavish collection of beloved classics contains three Poirot mysteries perfectly complimented by a Miss Marple outing.

Essential viewing for any fan of Agatha Christie, this lavish collection of beloved classics contains three Poirot mysteries perfectly complimented by a Miss Marple outing.

Agatha Christie never seems to go out of fashion because the plots of her stories are well crafted puzzles and, although their setting was contemporary on publication, they are now steeped in appealing nostalgia. They clearly have perennial appeal with at least 40 of her 66 detective novels adapted for the screen over the last century, most recently with a trilogy directed by Kenneth Branagh who stars as Hercule Poirot in remakes of Murder on the Orient Express (2017), followed by Death on the Nile (2022) and the spooky sequel, A Haunting in Venice (2023).

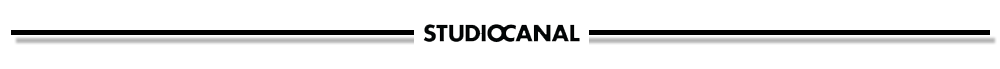

For many though, the star-studded adaptations from producers John Brabourne and Richard Goodwin, made in the 1970s and early-1980s are fondly remembered as definitive treatments. So, there are many who will welcome the crowd-pleasers in this attractive four-film box set from StudioCanal, carefully restored at 4K and presented in their pristine glory on both 4K Ultra HD and Blu-ray. With plenty of excellent extras accompanying each feature, it’s sure to please Agatha Christie aficionados, along with those wishing to recapture the movie magic of bank holiday family viewing back in the day which adds an extra kick of nostalgia. I wouldn’t be at all surprised if they catch on with a new, younger audience who may enjoy them with some irony, perhaps while partaking in spiffing 1930s cosplay with cocktails. Think I’ll give the Daiquiri a miss, though… make mine a ‘Between the Sheets’.

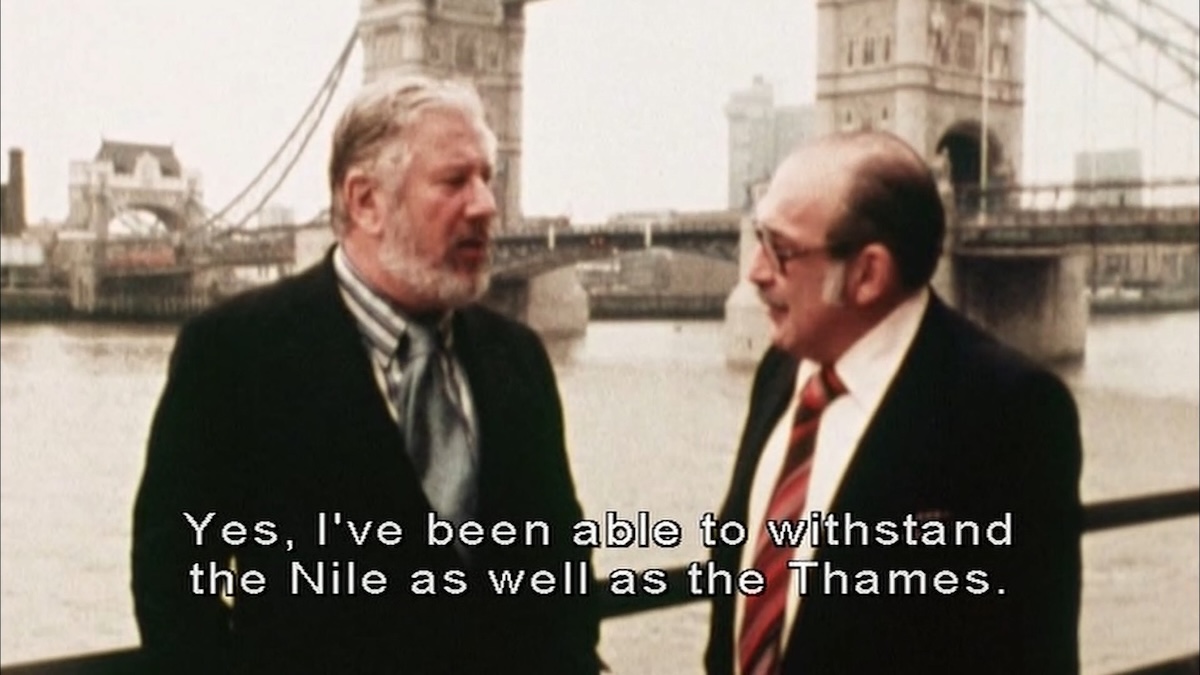

Although the titles presented here are of varied quality, each one has its own charm and for those of a certain age, the cast lists read like a who’s who of familiar faces that seemed ubiquitous on our screens, big and small, for a good chunk of the 20th-century. For me, Murder on the Orient Express (1974) is the highlight, which shouldn’t be surprising as it renewed interest in whodunit mysteries and was an unexpected box office hit and pivots on a superb portrayal of Hercule Poirot (Albert Finney). However, the other two stories included here and featuring a reinvented Poirot (Peter Ustinov) are certainly welcome, with Death on the Nile (1978) and Evil Under the Sun (1982) showcasing exotic locations and laced with sharp dialogue, acerbic wit and subtle humour. Sandwiched between those two titles is The Mirror Crack’d (1980), which misfires on many levels and failed to launch a spin-off film series featuring Miss Marple (Angela Lansbury). Part of the problem is that the spinster sleuth seems almost superfluous to the narrative … plus she just isn’t Poirot.

Agatha Christie’s very first published novel featured Hercule Poirot, the quirky Belgian detective destined to be more famous than C. Auguste Dupin and to become a household name alongside Sherlock Holmes. She wrote The Mysterious Affair at Styles in 1916, while working as a volunteer, unpaid nurse in a Red Cross hospital for the war-wounded. Her debut detective novel was later serialised in 18 parts for The Times newspaper, February to June 1920, before being published as a single volume later the same year in the USA and finally in the UK in 1921.

The murder mystery, set around the small Essex town of Styles St Mary, establishes Poirot as a refugee convalescing from injuries sustained on the battlefield. The plot templated many tropes of the classic whodunit that Christie would become synonymous with. The story is set within an enclosed environment, in this case an isolated country manor house. A group of assorted characters gather there. Each of them, it seems, has something to hide. There’s a murder mystery that we must try to solve ahead of the sleuth by considering a set of clues, many of which are red herrings, of course. The story was accompanied by illustrations including a sketch of the murder scene and a map of the house layout—thus the conceptual origin of the popular board game, Cluedo.

Poirot went on to appear in 33 of her novels and more than 50 short stories. Although not the first film inspired by the works of Agatha Christie, Alibi (1931) is believed to be the earliest direct adaptation of one of her novels, The Murder of Roger Ackroyd, which was first published in 1926 and holds the Crime Writers’ Association accolade as the best crime novel ever written. The film starred Austin Trevor as the first screen embodiment of Hercule Poirot, though no known prints survive.

David Suchet has since become indelibly linked with Poirot after playing the character in the long-running television series Agatha Christie’s Poirot (1989-2013). But before him, Peter Ustinov was Poirot in the public consciousness because of his six larger-than-life screen portrayals, two of which are included here. However, before Ustinov assumed the mantle, the super sleuth had been fleshed out by the only actor to receive Christie’s personal endorsement, Albert Finney…

A disliked financier is murdered on board the famous train and Hercule Poirot must identify the culprit but all the clues are confusing and contradictory.

The opening presents us with a recap of events, complete with grainy vérité-style footage and spinning newspaper headlines, surrounding the abduction, ransom and eventual murder of ‘The Armstrong Baby’—a fabrication closely echoing the real-life kidnapping and killing of two-year-old Charles Augustus Lindbergh Jr. in 1932, which was branded ‘crime of the century’ by the US press. This case would have swamped the headlines while Christie was writing the novel, but its inclusion may well have been back-engineered to fit the immensely inventive plotline that follows. After this mini-movie effectively deploys the dark visual grammar of a horror film, the entire tone shifts, transporting us to the glaring light of day in the exotic Istanbul locations.

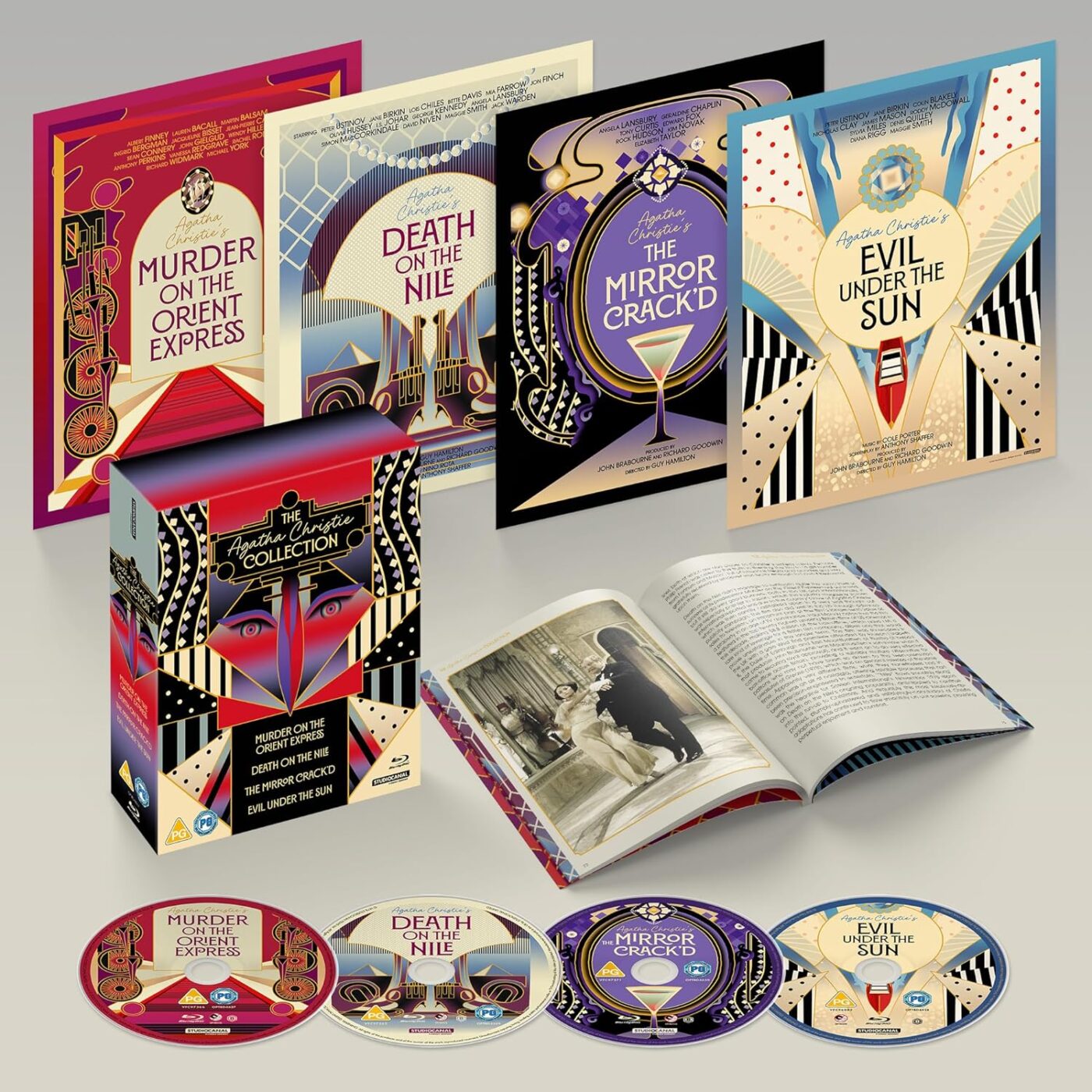

Sidney Lumet brings a lighter touch along with his dialogue-driven approach that reliably showcases the on-screen talent. He had a reputation for making movies with heavy themes, often with prolonged adversarial scenes where power dynamics quickly shifted during intense verbal exchanges. Films like The Hill (1965) made 10 years before and The Offence (1973), just the previous year, come to mind. Both starred Sean Connery who is reunited with the director here. He’s not the only A-lister in a supporting role either, alongside the underused Michael York, Jacqueline Bisset, Vanessa Redgrave, a late-career Lauren Bacall, and Ingrid Bergman, who received the Academy Award and a BAFTA for ‘Best Supporting Actress’ as Greta Ohlsson.

On first pass, one may think she isn’t that good but, as with most of the cast here, she’s acting a character who is pretending to be something other than she is. It takes bravery for an established actor to attempt this sort of layered performance, and it takes skill to pull it off so well. The thing is, she’s not the only one doing so here.

As with many Agatha Christie mysteries, more than one character has something to hide and seems suspicious. Of course, the plots of her novels, especially those that have been made into popular films, are now so well known that many viewers will already be aware of the various twists and surprises. But just in case, I’m not going to give too much away. For the purposes of these reviews, I made a point of watching these classics with a group of mixed ages, including youngsters who didn’t already know whodunnit. It was interesting that those more used to today’s rushed narratives found the deliberate pacing gripping till the end and couldn’t confidently predict the outcome until Poirot’s reveal. Also, on subsequent viewings, it’s surprising how many little nuances one overlooks, and I’d say this version of Murder on the Orient Express cannot be fully appreciated in just one sitting. Certainly, the central performances seem so different when one knows what’s going on and this is a most impressive achievement for a film that could so easily have been nothing more than a punchline plot. Kudos to the director and his clever cast.

Albert Finney was nominated for the ‘Best Actor’ Oscar and despite losing out to Art Carney, for Harry and Tonto (1974), he’s superb in the lead. His transformation is incredible, especially when compared to other roles around this time, for example another very different detective in Gumshoe (1971). He completely inhabits his Poirot from posture and grand gesture right down to subtle phrasing and meticulous nuance. His hunched stiffness attests to the character’s injuries that invalided him out of the Belgian army. His unassuming demeanour when observing the behaviour of others is counterpointed by passionate discourse when haranguing them in pursuit of a truth. It’s a shame this is the only time he got to play the part. The acting of his co-stars can come across as rather theatrical at times though he brings the best out in them and easily holds his own in every scene. Although their screen time is limited, John Gielgud and Wendy Hiller gave us some standout moments, lacing their lines with comedy timing and keeping things light despite some dark themes.

Murder on the Orient Express was relatively cheap to make and the fact that most of the action would be confined to simple, though beautifully dressed, sets was a major factor in finding funding. Comparatively cost-effective production meant that more money was available to hire a cast made up entirely of top names or veteran character actors—necessary to carry the clever dialogue, written with sparks of Oscar Wilde-grade wit by Paul Dehn. He had an impressively varied track record having penned Goldfinger (1964) for Connery’s Bond and Anatole Litvak’s unusual murder mystery, The Night of the Generals (1967). Here, he was fresh from a stint of writing the four sequels for Planet of the Apes (1968).

Cinematographer Geoffrey Unsworth perhaps overused diffusion filters to mitigate the sometimes-harsh lighting and soften the features of the cast in close-up. Maybe this was a concession to flatter some of the stars who would have been self-conscious of their age. This gives the whole movie a distinctive visual cohesion but of course, no amount of 4K scanning could or should make it significantly crisper and the resultant dreamlike atmosphere is immersive.

One of my all-time favourite cinematic anecdotes is recounted a few times on the disc’s assorted extras: When we reach the part of the plot where the characters all need to be confined in an isolated environment, the train becomes snowbound. Not only does this contain the suspects, but it also introduces a time factor as Poirot must solve the case before the relief train reaches them with its fitted snowplough. Apparently, the location of Pontarlier near the Swiss border was selected for a stretch of rail, disused due to its regular blockages with heavy snow. However, as the day of the shoot approached there was atypically no snow. At considerable expense, producer Richard Goodwin hired 30 lorries to transport snow from higher Alpine slopes. As they were in transit, a sudden spectacular snowfall rendered all roads impassable. The train was genuinely, and very photogenically, snowbound and the dismayed truck drivers were prevented from delivering their urgent cargo of snow… by snow.

The film was even more successful than expected, earning broad acclaim and doing impressive box office business. With a budget of just $1.4M—half of which went on the cast—it recouped around $38M. This story had first appeared as a serialisation in the Saturday Evening Post under the title Murder on the Calais Coach in 1934 and this excellent adaptation skilfully bridges the intervening four decades, melding thirties nostalgia with seventies sensibilities. Of course, now the further five decades since it was made has added yet more layers of nostalgia which has only increased its appeal.

UK | 1974 | 128 MINUTES | 1.66:1 | COLOUR | ENGLISH • FRENCH • GERMAN • TURKISH • ITALIAN • SWEDISH • HUNGARIAN

A spurned lover pursues her ex-fiancé and his new wife on their honeymoon in Egypt and murder soon ensues onboard the Nile cruise ship Hercule Poirot is also travelling on.

Not a snowflake in sight for this sun-drenched yet surprisingly dark and murderously entertaining mystery that frees us from the confines of train carriages only to finally return to the enclosure of a riverboat. During some establishing scenes in typically English lanes and a manor house, we are introduced to Jacqueline de Bellefort (Mia Farrow) and her fiancé Simon Doyle (Simon MacCorkindale) who seems more interested in the young, beautiful, not to mention very wealthy heiress Linnet Ridgeway (Lois Chiles). We then follow Simon and Linnet on their honeymoon and find ourselves in the vast desert vistas of Egypt among impressive ancient landscapes dominated by temple columns, colossal statuary, the Sphinx and the great pyramids at Giza. At the time, such exotic locations were enough of a draw to satisfy an audience with Death on the Nile being the first major movie to be shot in post-war Egypt.

Director John Guillermin makes the most of the scenery with a good amount of the first act showcasing the locations and establishing that all the key cast are there, in Egypt. The director was best known at the time for The Towering Inferno (1974), another movie famed for its massive cast of A-listers and familiar has-beens. Here, he’s heavily reliant on veteran cinematographer Jack Cardiff, best known for his luscious colour work for Michael Powell and Emeric Pressburger on such classics as A Matter of Life and Death (1946), Black Narcissus (1947)—for which he won an Academy Award—and The Red Shoes (1948).

Apparently, Albert Finney was offered the lead again, but declined and so the versatile character actor Peter Ustinov accepted the challenge, reinventing the character as more genial though just as arrogant. He smoothed off the edges with a less-guarded emotional intelligence and sharp sense of humour. Under the pen of Anthony Shaffer, the script was relentlessly witty and cleverly ironic. Some of the overblown dialogue becomes distracting and reduces character to caricature—particularly the verbose lush Salome Otterbourne (Angela Lansbury). The cast do seem to be having fun with the highly stylised dialogue, though and the most memorable moments involve Bette Davis, David Niven, and a shrill performance from Mia Farrow.

Filming in Egypt presented all sorts of logistical troubles, such as lack of telephones and a necessity to begin shoots before 4 a.m. so they could finish before the temperatures became physically and technically prohibitive around noon. However, after establishing the locations with a gruelling seven-week shoot—including building dolly tracks all the way up the slopes of one of the pyramids—the bulk of the interiors and scenes on the deck of the paddle boat were shot at Pinewood Studios. This facilitated the third act when the action and characters are confined to the boat awaiting Poirot’s verdict.

Before the dénouement, though, the film turns into a neo-giallo with a respectable body count and some brief but explicit deaths. A bullet to the head or a blade to the throat results in pools of blood puddling around the corpse. Not quite enough to be realistic, but definitely a nod in that direction and probably more than expected in a PG-rated ‘family film’ of the time. The solution reminds us of those opening scenes that we may well have forgotten about after so much time spent in Egypt.

UK | 1978 | 140 MINUTES | 1.85:1 | COLOUR | ENGLISH • FRENCH • ARABIC • GERMAN

A Hollywood film being made in a quaint English village is disrupted by an unexplained death that is soon revealed as murder. The gentile Miss Marple helps her nephew uncover the killer.

Intended to launch a spin-off series of Marple movies, but a terrible choice for this purpose as the elderly amateur detective (Angela Lansbury) isn’t in it very much and never directly interacts with the key characters and suspects until the finale when she steps in and delivers the solution with very little finesse. For the most part she operates by proxy through her nephew (Edward Fox), presenting opportunities for her to chat with rose pruners in hand, I kid you not.

Despite concerning dark deeds such as blackmail, murder, suicide and even murder-suicide, an Agatha Christie whodunnit is usually great fun and reliably entertaining. Death on the Nile and Evil Under the Sun are two such examples. The Mirror Crack’d, however, is an imbalanced narrative with a frivolous first act that approaches comedy before heading into a fragmented second act and finally a truly depressing third.

Although Murder on the Orient Express was also inspired by a real and very tragic case, the ensuing story is entirely fictionalised, in an alternative late aftermath and delivers one of the best twists in mystery thriller history. In fact, providing one doesn’t mind a bit of made-up murder, it’s ultimately uplifting.

Based on a web of cause and effect, The Mirror Crack’d, if anything, re-imagines events lifted from the personal life of Hollywood star Gene Tierney with an even more tragic outcome, which is saying something. It’s quite silly to start with but ends up being no fun at all, and what a sad story for the legendary Elizabeth Taylor’s attempted comeback. Thankfully, she still decided to return to acting, mainly for TV movies with her last notable big-screen appearance being as Pearl Slaghoople in the live-action The Flintstones (1994).

Angela Lansbury would have made a great Miss Marple and is wasted here, the only time she was given the opportunity to play the part. Although it probably landed her the starring role as Jessica Fletcher in the long-running CBS TV series Murder She Wrote (1984-1996). Agatha Christie felt that older women were underrepresented in fiction and films and sought to redress this and, tiring of Poirot’s company, created an unlikely amateur detective with the fussy sometimes snobby spinster Miss Jane Marple. The character first appeared in a set of short stories published in the popular British literary magazine, The Royal from 1927, followed by the full-length, The Murder at the Vicarage, in 1930. And so, the cosy crime genre was born with Marple appearing in a dozen novels and some 20 short stories.

UK | 1980 | 105 MINUTES | 1.85:1 | COLOUR | ENGLISH

Hercule Poirot is hired to track down a missing jewel but gets embroiled in a puzzling case of murder instead.

After directing The Mirror Crack’d, Guy Hamilton got a chance to redeem himself with this highly entertaining follow-up with Peter Ustinov reprising the role of Poirot. For me, this is the most unadulterated fun of all four films and although there’s absolutely cold-blooded villainy from the who-that-done-it, the sunny climes and comedy aspect warm things up throughout.

It boasts another sharp script from Anthony Shaffer, this time with The Mirror Crack’d writer Barry Sandler lending a hand. Its lively dialogue is crammed with rapid repartee and a dash of un-PC retorts that would now be labelled as outdated comedy even though the easy bigotry of some of the characters is intended as a knowing critique of certain social strata. Shaffer changed the order of events around a little and omitted or merged certain characters. He also transposed the female Emily Brewster into the flamboyantly peevish Rex (Roddy McDowell).

Many Agatha Christie stories are set in the socialite whirl of the wealthy classes, a scene she was very familiar with as the backdrop to her adolescence and debutante years. The archetypes and stereotypes she used in her stories and, to some extent established, satirised and lampooned the upper-middle classes to which she herself belonged. The humour was meant for readers to whom these characters and caricatures would seem familiar, though I wonder how many saw themselves in them. Although she does make political points regarding social inequalities, and often the villains are products of the class system and its sense of entitlement, she doesn’t dwell on such things at the expense of entertainment.

After another incongruous opening sequence involving the discovery of a woman’s body on the North Yorkshire moors, Hercule Poirot is hired by an insurance firm to investigate a fraudulent claim for a fake piece of ostentatious jewellery. He follows the suspected fraudster Sir Horace Blatt (Colin Blakely) to his yacht and subsequently to an island resort hotel in the Adriatic Sea where an assortment of rich showbiz types are vacationing including characters played with broad strokes by Maggie Smith, Diana Rigg, James Mason, Jane Birkin, and Nicholas Clay who I instantly recognised as Sir Lancelot from John Boorman’s Excalibur (1981). The original story had been set in Devon, but the producers knew exotic locations attracted audiences and so the locations were shot in sun-soaked Majorca which was only just becoming popular as a holiday destination for the elite at the time. As a protégé of Jack Cardiff, Christopher Challis seemed a natural choice to take over as cinematographer, and he really makes the most of the bright clarity, pale terrain, and crystal waters.

The Crime Writers’ Association has voted Agatha Christie the best crime writer of all time and according to UNESCO’s definitive list of works in translation, The Index Translationum, she is the most-translated author. With some 100M copies sold, her novel And Then There Were None, originally published in 1939 under a different title, is certainly one of the bestselling novels of all time. Her stage play, The Mousetrap, holds the world record for the longest initial run since premiering in London’s West End in November 1952 and continuing with only a brief interruption in 2020 during COVID-19 lockdowns. This year, 2025, it has surpassed 30,000 performances.

UK • USA | 1982 | 117 MINUTES | 1.85:1 | COLOUR | ENGLISH • GERMAN • FRENCH

The restorations and careful colour grading by Silver Salt Restoration UK were scanned in 4K 16-BIT from the original 35mm negatives. It’s estimated that each film took over 200 hours of work to manually clean and carefully remove sparkle, density fluctuation, dirt, and scratches. The prints are as good as they can ever be as they are now clear right down to the film grain and the greyscale and colour tones have been carefully matched to bring out details in dark areas and minimise white-out. The StudioCanal project was supervised by Jahanzeb Hayat and Mariana Ledesma.

The four-disc box set features a 64-page booklet plus four posters of brand-new artwork designed by W$YK. Not available at time of review.

directors: Sidney Lumet (Orient) • John Guillermin (Nile) • Guy Hamilton (Mirror & Evil).

writers: Paul Dehn (Orient) • Anthony Shaffer (Nile & Evil) • Jonathan Hales (Mirror) • Barry Sandler (Mirror & Evil) • (All based on the novels by Agatha Christie).

starring: Albert Finney, Lauren Bacall, Martin Balsam, Ingrid Bergman, Jacqueline Bisset, Jean-Pierre Cassel, Sean Connery, John Gielgud, Wendy Hiller, Anthony Perkins, Vanessa Redgrave, Rachel Roberts, Richard Widmark, Michael York, George Coulouris, Denis Quilley & Colin Blakely (Orient) • Peter Ustinov & Jane Birkin (Nile & Evil) • Maggie Smith (Nile & Evil) • Angela Lansbury (Nile & Mirror) • Lois Chiles, Bette Davis, Mia Farrow, Jon Finch, Olivia Hussey, I.S Johar, George Kennedy, Simon MacCorkindale, David Niven & Jack Warden (Nile) • Geraldine Chaplin, Tony Curtis, Edward Fox, Rock Hudson, Kim Novak & Elizabeth Taylor (Mirror) • Colin Blakely, Nicholas Clay, James Mason, Roddy McDowall, Sylvia Miles, Denis Quilley & Diana Rigg (Evil).