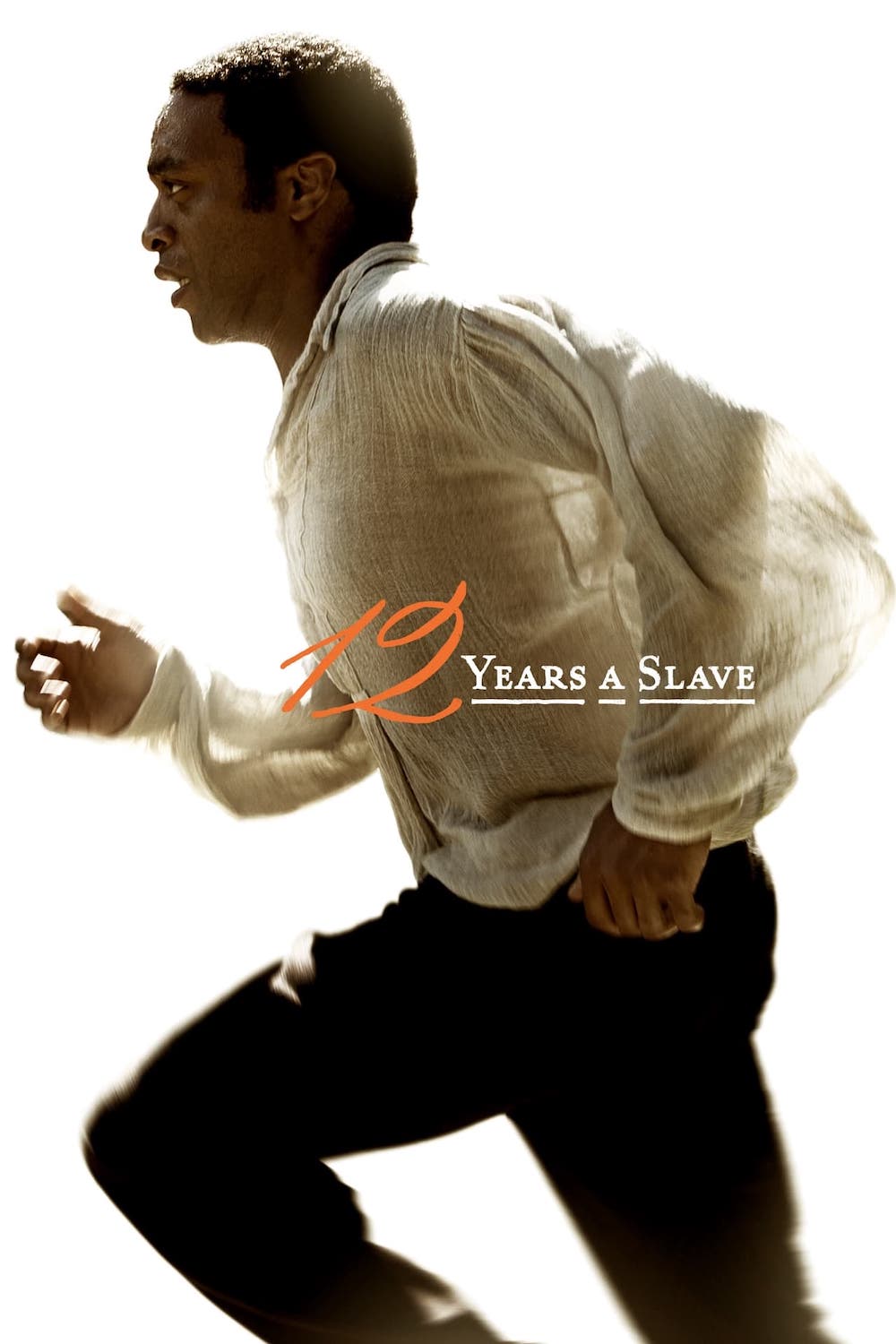

12 YEARS A SLAVE (2013)

In the antebellum US, a free black man from upstate New York is abducted and sold into slavery.

In the antebellum US, a free black man from upstate New York is abducted and sold into slavery.

Solomon Northup (Chiwetel Ejiofor), a free man and talented violinist, is captured and sold into slavery while on a trip to Washington, D.C. Beaten and whipped into submission, he’s forced to renounce his freedom under the threat of further punishment. Northup’s story, told in the critically acclaimed film 12 Years a Slave, is a tapestry of human suffering. Through his lived experience, we’re given a glimpse into the dehumanizing effects of colonialism and the unimaginable horrors of the slave trade in America.

With expert performances, vivid characters, striking imagery, and unshakeable direction from Steve McQueen, 12 Years a Slave demonstrates how dehumanising evil can become commonplace within a colonial system when there’s profit to be made.

When Solomon stirs in a darkened room, his surroundings illuminated only by a small square of light, the clinking of chains will sink your heart. He panics and stands to face his captors. Their brazen denial of his freedom creates a pit in his stomach. “Produce your papers,” they demand. Their simple request bears with it a horrifying implication: that a person’s existence as a human being can rest on the quick exhibition of a slip of paper. “You ain’t from Saratoga. You from Georgia. You ain’t a free man. You’re nothing but a Georgia runaway.”

The Kafkaesque nature of Northup’s situation is undeniable: he’s inexplicably imprisoned and stripped of his human rights, with no clear explanation or hope of escape. Like Gregor Samsa in Kafka’s The Metamorphosis, Northup is transformed into something subhuman, something to be treated with indifference or even cruelty.

For others in Solomon’s slave pen, life is already forfeit. None will listen to Solomon, as his fellow slaves remind him—who will lend them a sympathetic ear? He’s in a new state with no friends, family, or means of identification. Who would believe his story?

Whatever plan Solomon devises to rectify their wrong, his new companion Clemens (TK) assures him that his situation is hopeless. There will be no escape, no grand battle for justice. They will be brought to a southern state, as is customary. Solomon surmises despairingly, “Once in a slave state, I suppose there’s only one outcome.” This is all that needs to be said for them to understand their fate.

McQueen conveys the torment of his protagonist and supporting characters with every frame of the film. His background as a visual artist is evident in the opening shot, which resembles a landscape painting: slaves stand in a field of tall, perennial grass, receiving instructions on how to chop sugar cane. The shot breathes, flowing through the grass, and time and place become undefined and diffuse, meshing together the years Solomon has spent in servitude with his memories of family and home.

One early shot is particularly effective at conveying the central themes of the story. As the slave ship churns its way down to New Orleans, the turbine propelling it forward becomes a chilling image of an unstoppable machine of relentless cruelty and dehumanization. The slavers stoking the engine’s fire are merely cogs in this machine, dehumanized by the very system they serve.

The imagery utilised is reminiscent of John Steinbeck’s The Grapes of Wrath, particularly in how Steinbeck refers to capitalism as an all-consuming, merciless entity. Perhaps what is so valuable from Steinbeck’s tour de force is his insight into how the capitalist system rots a person’s soul: “Some of the owner men were kind because they hated what they had to do, and some of them were angry because they hated to be cruel, and some of them were cold because they had long ago found that one could not be an owner unless one were cold. And all of them were caught in something larger than themselves.”

This passage, though used to portray the mindset of bankers evicting families, could just as easily describe the slavers, plantation owners, and overseers in McQueen’s epic. Several characters are keenly aware of their brutality, but for most, profiting from the system is easier than opposing it. The slave trade, a faceless, unstoppable engine, devours everything in its path: individuals, families, states, and entire races. It makes no difference.

Edmund Burke, an Irish statesman and philosopher, famously said, “The only thing necessary for the evil to triumph in the world is for good men to do nothing.” While none of the characters in this story are truly good, with the possible exception of Bass (Brad Pitt), some are clearly averse to the systematic abuse they witness but find themselves either powerless or unwilling to change it.

Much like Steinbeck’s bankers, Ford (Benedict Cumberbatch) is kind because he despises the truth of what he is: a slaver, a profiteer from human suffering. After Northup confesses to him that he’s a free man, Ford does nothing to help—not because he’s not wracked with guilt, but because it’s easier not to. He has a debt of which he is mindful, after all.

What makes McQueen’s film so compelling is that its characters aren’t caricatures, as is often the case in films about horrific periods in history. Instead, they embody the lawful evil that was rampant in our society at the time, and arguably still exists today. This system is rife with apathy: Freeman is cold because it’s the only way to be an owner, and it’s also the best way to make money. When criticized for separating Eliza from her two children, he responds without emotion, saying, “My sentimentality stretches the length of a coin.” This detached approach to human life makes him an expert salesman, capable of determining just how much he can earn from each pound of flesh.

Rationalisation is a powerful tool of subjugation, as potent as indifference. Explanations for the horrors committed against enslaved people can be found through selective interpretations of The Bible, providing a convenient sedative for any turbulent emotions one might have. According to Epps (Michael Fassbender), scripture adroitly separates humans from animals, with African Americans finding themselves in the latter category. In his book Homo Deus, Yuval Noah Harari writes on how humans deftly avoided moral quandaries in their maltreatment of livestock by creating cosmological myths. These tales prove that humans are of higher importance (as they are the only creatures in possession of a soul), so should not concern themselves with the suffering of mere animals. Similarly, Epps feels no shame in whipping Patsey to within an inch of her life: “A man does how he pleases with his property.”

Amidst the torment of slavery, the theme of hope triumphing over despair emerges. Solomon, the protagonist, refuses to give up on his dream of escaping and returning to his family. He rebukes those around him for allowing themselves to be overwhelmed by sorrow, warning that even grief can be dangerous. Yet, he cannot provide a satisfactory answer to their dejection: unlike him, they have no family to think of, no previous life to escape to, and therefore, no real hope at all. When Patsey asks Solomon to drown her in the swamp, he dismisses her request as mere melancholia. However, her impassioned plea for him to end her life, to have the strength to do what she cannot, is truly heartbreaking, as it’s presented as the only viable means of escape. Lupita Nyong’o’s Academy Award-winning performance is sure to bring tears to your eyes.

Solomon’s victories in indentured servitude only led to worsening conditions. His ingenious scheme to transport lumber via the river puts him in conflict with Tibeats, who lynches him. Northup survives, but only after dangling from a rope for hours, tiptoeing in the mud to keep his breath. Behind him, people continue about their daily lives, children playing unconcerned. The juxtaposition of innocence and cruelty is only more compelling through Sean Bobbitt’s magical touch on the camera and McQueen’s beautiful composition.

Sometimes it seems like he might escape. Once, he tried to make ink from blackberry juice to write a letter, but his ingenuity was for nought; the juice wouldn’t dry. He turned to a man named Armsby (TK), who’d expressed dissatisfaction with his cruel job as an overseer. But Solomon’s trust nearly cost him his life.

Although chilling, Solomon’s final triumph is tempered by the knowledge that he’s one of the few enslaved people who managed to escape. In Hunger (2008), McQueen explored the workings and pathology of a broken system through the effects on one person. He does the same here: upon returning home after so many years, Solomon Northup finally sees his family again. After apologizing for his dishevelled appearance, the only words he can muster are “Forgive me…”

12 Years a Slave has been dismissed by some as exaggerated, with critic Armond White even terming it torture porn. While the polarising White is no stranger to courting controversy with his contentious opinions, it seems obvious this is deliberately inflammatory, but little more. Such an incendiary rejection may attempt to conceal the talent on display, but most who have seen this film would agree that there’s more here than superficial violence.

McQueen’s masterpiece is a feast for the eyes and the mind, with incredible performances, mesmerizing camerawork, and a wealth of ideas. It comments on our willingness to turn a blind eye to horror, even when it’s happening right in front of us. Even Solomon, a free man who was kidnapped and enslaved, was unperturbed by the sight of a slave being hurried away in New York. Evil isn’t personified in any single way, but in all of its multitudinous forms: greed, apathy, covetousness, envy, vice, and wrath.

What perhaps lingers the most with audiences is the palpable sense of an amorphous, engulfing system. Like a black hole, it traps all who enter, leaving them hopeless and lost. Everyone’s caught in something larger than themselves, a machine that no one can stop alone. This may be why Northup became a prominent leader in the abolitionist movement after his return.

While Hunger was a striking directorial debut, 12 Years a Slave is even more remarkable. It ranks among the most harrowing and truthful films about American slavery, alongside Schindler’s List (1993) and Come and See (1985). That McQueen’s third feature is mentioned in the upper echelons of film history is a testament to his skill and vision.

It’s difficult to define when a film becomes a classic. Some argue that 10 years is the benchmark, but I believe this is too short a time period to judge a film’s place in cinematic history. I recently rewatched 12 Years a Slave, and the visceral response I had was unlike any other, mostly because the events depicted are not exaggerated. We witness genuine human evil—honest, earnest, and untheatrical depravity. It was a film that needed to be made, and it remains worth revisiting.

USA | 2013 | 133 MINUTES | 2.35:1 | COLOUR | ENGLISH

director: Steve McQueen.

writer: John Ridley (based on the book ‘Twelve Years a Slave’ by Solomon Northup).

starring: Chiwetel Ejiofor, Michael Fassbender, Lupita Nyong’o, Benedict Cumberbatch, Paul Dano, Paul Giamatti, Sarah Paulson, Brad Pitt & Alfre Woodard.

2 Comments

This site uses Akismet to reduce spam. Learn how your comment data is processed.

Slavery was commonplace everywhere, and it was even an acceptable practice according to The Bible. Of course, the British did abolish slavery in 1807 – a mere 31 years after the US was formed, where it could have followed that example.

Oh, dear . . .

We do realize that human slavery, that absolute rock-bottom of all the cost-of-labor-saving devices, did not begin in the nascent United States on July 4th, 1776? (Hand to mouth in feigned shock.) It was actually a legacy, almost a bequest, a gift from our supposedly superior Euro-betters, sewn into the fabric of the infant nation’s teething blanket as handily as the thirteen original stars on that fabled banner. Ready-made conflict spanning the first eighty years, culminating in the historically inevitable carnage of the Civil War, the deadliest, bloodiest in U.S. history (at present.) We are still paying the price for that baked-in socio-economic stratum courtesy of the minders in London, Paris and Madrid. (Yes, I know……Hard facts hit hard.) A stale (or fresh, depending on your taste) biscuit to digest with your bitter tea (….courtesy of India.) Ta.