MARTYRS (2008)

A young woman's quest for revenge against those who kidnapped and tormented her as a child leads her and a friend, who's also a victim of child abuse, on a terrifying journey into a living hell of depravity.

A young woman's quest for revenge against those who kidnapped and tormented her as a child leads her and a friend, who's also a victim of child abuse, on a terrifying journey into a living hell of depravity.

Pascal Laugier’s Martyrs has a long-standing reputation as a shocking, transgressive cornerstone of modern horror; its title is only a breath away whenever ‘extreme horror’ is the topic, referenced as if part of a checklist for audiences seeking to test their stomach and earn their credibility. You’d think that a film like Martyrs would be interchangeable with Hostel (2005) or The Human Centipede (2009), but that couldn’t be further from the truth…

To watch Martyrs on its own terms, away from the controversy, away from the claims that Laugier is nothing more than a glorified peddler of snuff images, is to see a film that goes beyond shock and gore, that holds in one hand the elements of a traditional exploitation horror, and in the other, a remote control to a shock collar worn around our necks. “You expected to have fun?”, his taunts seem to echo in our ears.

Martyrs is more interested in the fallout rather than the process. Laugier structures his film with an obfuscating editing pattern, cutting between the past and the present, as if the howling wounds of his characters have grown to cover yesterday, today and tomorrow. It’s effectively disorientating, a traumatised life, or lives, existing as one long day. It captures the dazed inability to process time, to buttress the past to stop it collapsing in on us now. Our trauma may have happened 10 years ago, or it may have happened 10 minutes ago. It’s how it feels.

And so the first thing we see is a girl, head shaved, beaten, clothes tattered, limping from captivity and towards what we assume—hope—is freedom. We don’t know who she is or what has happened to her. The concrete is merciless on her bare feet; she can only groan, cry out. She doesn’t seem to know where she is.

That Laugier starts his film in media res on this escape gives the effect of this being the end of a film that we have not been privy to. We’re hurled into the tumult that occurs after the wounds have been ruptured—we don’t get a glimpse of a world in which things are okay. We begin in darkness, running towards the light, but it’s a trick. We are heading further into the darkness, not away from it.

Laugier soon offers us another ending to another film we haven’t seen. 15 years on, the now-adult escapee is on the doorstep of a middle-class family of four. Tears are in her eyes, wounds illustrate her face, she wears a black beanie and carries a shotgun. Her name is Lucie (Mylène Jampanoï), and the actress burns with a terror and rage that seems to hold her molecules together; without them it feels as if she might dissolve. She’s looking for the people who locked her up 15 years ago. She has come for revenge.

Jampanoï’s intensity is frightening to behold, and masterfully layered with a vulnerability that segues into a reactive, impulsive violence. She calls her accomplice, Anna (Morjana Alaoui), from the house in a panic. Lucie and Anna first met in an orphanage after Lucie escaped captivity, and after Anna was rescued from her own onslaught of abuse by her parents. The girls form the sort of close, protective bond that can only blossom from a solidarity between two people whose pain is alien to all others, that only makes sense to the other. How does anyone—let alone a child—divine answers or wisdom from such unrelenting darkness? If that’s all you’ve known, then the world to you will not look like it does to everyone else; they haven’t been witness to humanity’s true nature, Laugier suggests.

That question—how can human suffering and cruelty ever be fully comprehended—manifests its answer in the form of a humanoid creature, skinny, feral, vaguely feminine and growling, hunting and attacking Lucie. Anna can’t see it, but Lucie is insistent that she’s real. When Anna finds Lucie, she’s covered in slashes, caused by the creature, she claims.

Here, Martyrs gets as close as it ever will to traditional bump-in-the-night horror, but this stalking creature is haunting and visceral, gaslighting Lucie into questioning her own sanity—if the creature is but a manifestation of past suffering, then this only makes it more terrifying, not less; regardless of what is real and what can be fought, the ghosts we are left with will kill you just as violently as any ghoul.

Laugier uses imagery here that evokes self-harm, and indeed the ambiguity of his film encourages these readings—but his focus on character, of the humanity they try to retain even as everything else is stripped from them, means that Martyrs sidesteps edge-lord shock-value. Violence isn’t fun in Martyrs, and it isn’t supposed to be.

The filmmaker rarely plays violent moments for spectacle or thrill, and the most sustained montage of violence in the film is shatteringly sad, exhausting, and essentially gore-less. One of the girls is captured, chained to a metal chair, and force-fed gruel from metal dishes. She’s beaten by a hulking henchman. This goes on almost endlessly. She, we, are worn down, spirits broken.

The film fades to black repeatedly as this particular sequence plays out, each fade offering us the possibility of rest, of sleep, before slapping us awake and starting again, punches and kicks thundering down on a helpless victim. It’s gruelling, punishing, as if Laugier is disgusted by the audience’s desire to be entertained by violence.

Martyrs has been described as a cornerstone of the New French Extremity movement in horror, while others have dismissed it as torture porn or a splatter film. This is simply not true, and this 15-minute passage in the film’s middle section, this test of endurance, is not anything close to pleasurable. Laugier wants us to hurt.

Horror cinema is so often geared towards weightless violence, to guilt-free expulsions of bloodlust, that it seems necessary for a film like Martyrs to exist—particularly when a disproportionate amount of that depicted violence is aimed at women. Damien Leone’s wildly successful Terrifier films have conjured up the grindhouse, splatter-trash spirit for a new generation, and while his bloodbaths are impressive to behold, there has been no shortage of critics pointing out that women always seem to bear the brunt of the violence in those films.

I mention Terrifier because that’s the film people seem to believe Martyrs is—an arguably misogynistic parade of (mostly) women being gruesomely tortured while a loveable, marketable mascot pulls funny faces and claps. This is nothing new—from Fay Wray being lugged up the Empire State Building in King Kong’s sweaty mitts to Art the Clown quite literally pouring salt into a screaming woman’s wounds, horror directors seem to have a fixation with violence against women. Some directors will argue it sells more tickets, others that it’s a bit of fun, others that it’s actually somehow empowering.

The results vary from film to film of course, but last year’s ongoing question of the worth of this kind of horror after the release of Terrifier 3 (2024) is worth interrogating, and Martyrs seemed to be asking exactly this question in 2008. Why is it always women? And why, if two people are to be killed in a horror film, is it much more likely that the woman’s death will be sexualised, prolonged, scandalous?

As Martyrs progresses, Laugier pares back the plot and most external distraction—we’re in the dark, past the point of even hoping for answers once we finally receive them. “There is nothing left in the world but victims,” Anna is told by a captor. She’s unrecognisable from the beatings. “But a Martyr is something else. They bear all the sins of the earth. They give themselves up. They transcend themselves. They are transfigured.”

They sound like the justifications made by violent bigots—the people who despise and admire somebody at the same time, the people who morph their prejudice into something holy, divine. Denying their desire to see an ‘other’ harmed, denying violent lusts, we are left with people who do dreadful things because they believe they must be done, regardless of desire, because this is a person’s purpose. Specifically, Martyrs is about the prevailing delusion that the already oppressed must suffer even further cruelties for the progression of society, even enlightenment.

How, Laugier seems to ask, can we be content with using human beings as test subjects? How can we let people suffer, hurt, die—how can we cause these things—and argue it’s for the good of society? How can we allow people to die starving on the streets, to send women back to abusive partners, to allow and enact endless suffering—and still wash our hands and talk about how far society has come?

Morjana Alaoui’s performance as Anna is physical and exhausting to behold—there are long stretches with almost no dialogue, but Laugier trains his camera on her face, on the light in her eyes, crystalline with tears, her expression eventually tending towards that of someone who has gone beyond, who is witnessing some sort of afterlife.

Laugier’s 35mm cameras have a grit and texture to them, his images high in contrast and grain, so that when moments of clear beauty occur they are startling. Her head lolling, eyes fixed somewhere far off, bathed in circular light, Anna could be Renée Jeanne Falconetti in Carl Theodor Dreyer’s The Passion of Joan of Arc (1928).

And like Dreyer’s film, perhaps the most troubling thought is that this is all for nothing; that there is no transcendence, no martyrdom, no sainthood. Laugier, like Dreyer, hints at something beyond, at a divine reward—or at least peace—that might come. But like Dreyer, Laugier keeps us here and now, trapped between four walls, uncertain of whether we are witnessing sanctification or punishment.

Martyrs, then, doesn’t benefit from anything you’ve heard it described as. Laugier himself denounced the New French Extremity label his film was given, and points to Catholicism and depression as the key influences on his film. It results in a film quite unlike any of its supposed peers, a film with more weighing on its soul even than the nature of violence. Laugier instead gets to the very heart of human experience: we’re born, we suffer—and it’s our duty to decide for which cause we will suffer, or else it’s all for nothing.

FRANCE • CANADA | 2008 | 99 MINUTES | 1.85:1 | COLOUR | FRENCH • ENGLISH

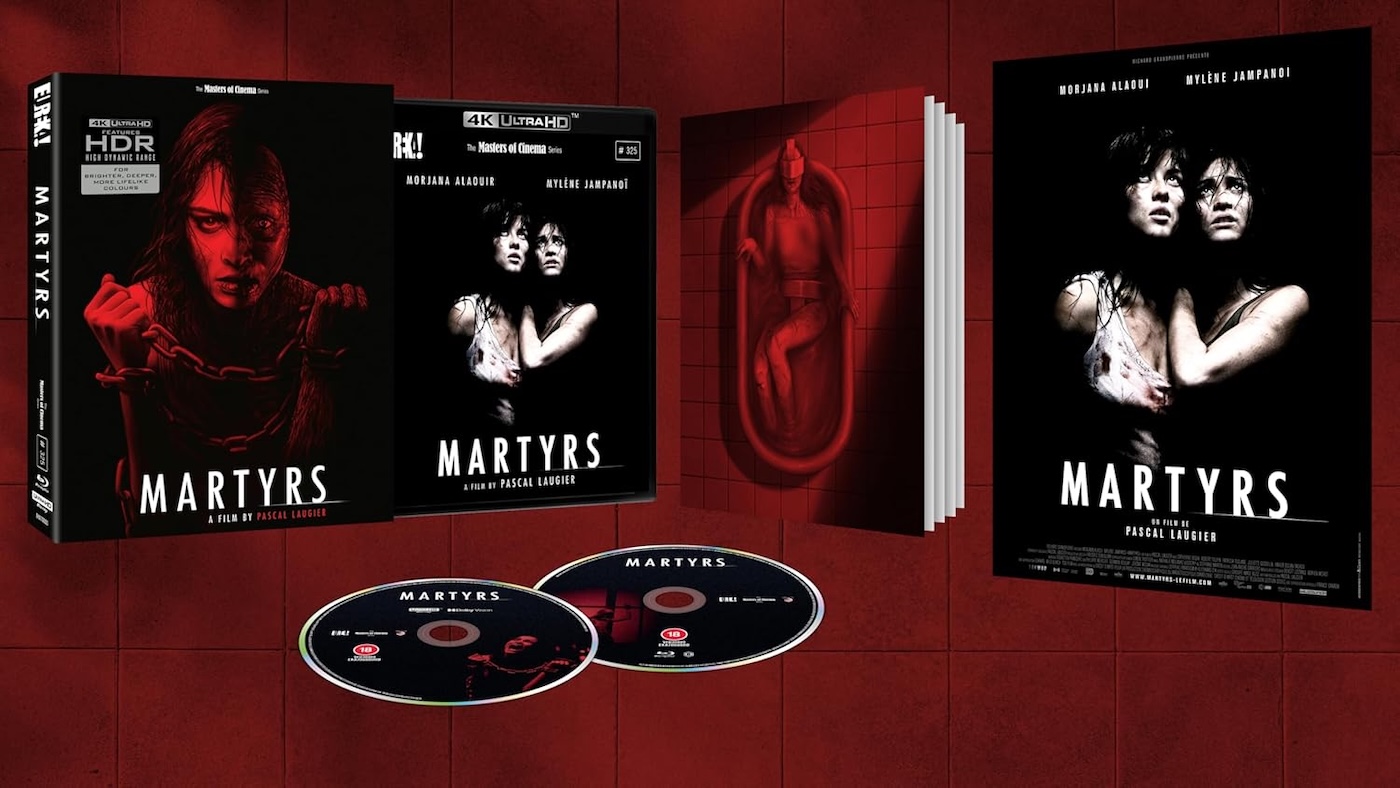

This new 4K restoration by Eureka Entertainment was taken from the original camera negative, and is presented in 4K (2160p) Ultra HD Blu-ray, in Dolby Vision HDR. Martyrs has a gritty, 35mm look which is captured beautifully with this 4K restoration.

It’s immediately clear it was shot on film, with a level of grain, texture and contrast that’s genuinely striking. The film’s colour palette is one of greys, whites and blacks, and each tone is presented with depth and vibrancy. Blacks are deep and realistic, skin tones even throughout.

The sound is particularly hefty and bass-heavy—each thud, crash and gunshot rattling the subwoofer. It all adds up to the best version of Martyrs that you can possibly see. It looks phenomenal.

writer & director: Pascal Laugier.

starring: Mylène Jampanoï, Morjana Alaoui, Catherine Bégin, Isabelle Chasse, Robert Toupin, Patricia Tulasne, Juliette Gosselin & Xavier Dolan-Tadros.