William Friedkin (1935-2023): More than a Two-Hit Wonder

An overview of the career of the late William Friedkin, director of The Exorcist, The French Connection, Sorcerer & Cruising.

An overview of the career of the late William Friedkin, director of The Exorcist, The French Connection, Sorcerer & Cruising.

William Friedkin, who died this week at the age of 87, topped the box office charts in 1973 with The Exorcist and had come close two years earlier with The French Connection (1971). Such early acclaim—he’d only moved from documentaries into narrative cinema in 1967—can be a hard act to follow (ask Orson Welles or Quentin Tarantino), as a filmmaker becomes so associated with their major triumphs that the rest of their work is overshadowed.

That is certainly the case with Friedkin. He has always been a biggish name on the back of that pair of films, and always had a coterie of fans—not least because the thriving state of horror today can, to a significant extent, be traced back to The Exorcist because it was a horror film that proves the genre could be intelligent. People who don’t know a single other Friedkin movie still know that one. He will always be “the guy who directed The Exorcist.”

Yet he was never an immediately recognisable auteur. Others afflicted at much the same time by the same lack of an obvious signature, despite their estimable filmographies, included Franklin J. Schaffner (Patton, Planet of the Apes, Papillon) and Richard Fleischer (Soylent Green, 10 Rillington Place, Barabbas), and perhaps it’s no coincidence that both started out, like Friedkin, as documentary filmmakers.

If there’s a “Friedkin style” the documentarian lack of frills is surely a large part of it. He described himself as a “one-take guy” who believed in “pragmatic truth”, and said he tried to make The Exorcist “with no sense of style.” He generally eschewed philosophising about his own films, although he happily did so on other topics. People should “draw their own conclusions” from The French Connection and The Exorcist, he once said.

Still, even if the Friedkin trademark might seem to be the absence of trademarks, there are traits which run through much of his oeuvre.

Beyond The French Connection and The Exorcist, the four highlights of his career are Sorcerer (1977), a loose remake of Henri-Georges Clouzot’s desperate-truck-drivers thriller The Wages of Fear (1953); To Live and Die in L.A. (1985), the epitome of lushly moody 1980s noir and perhaps his most visually arresting film, with its rich colours and careful compositions; Killer Joe (2011), his deliberately over-the-top comedy of incompetent, unlucky low-lifes; and Bug (2006), an atypical film for Friedkin in many respects—with the lead being a woman, and its intimate and easily-flowing conversation—but an unforgettable one.

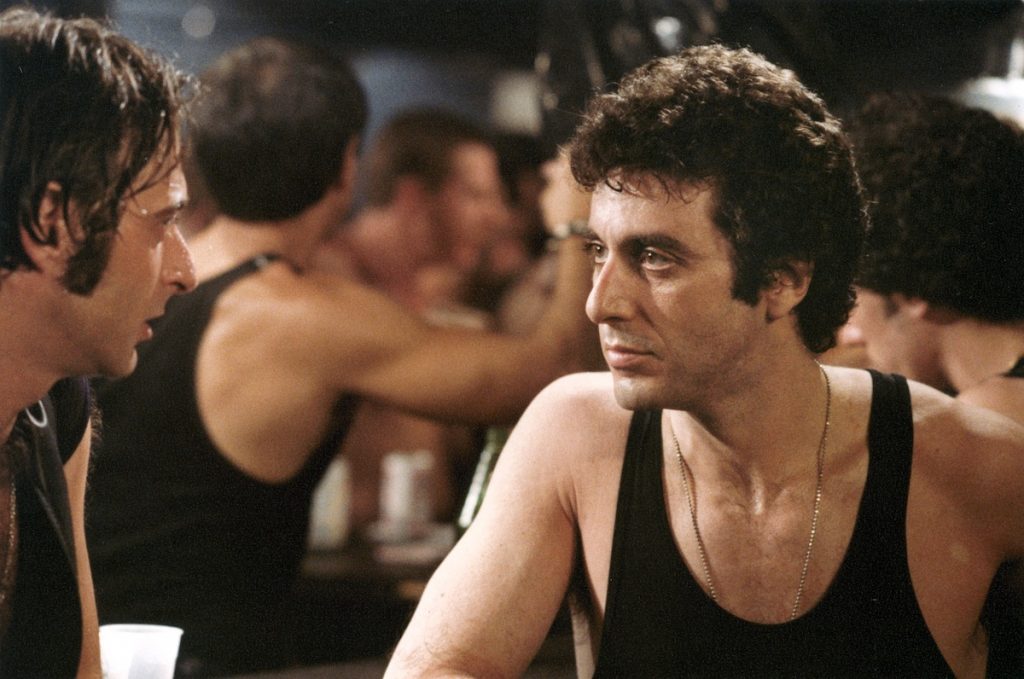

Not a highlight for all viewers but certainly a fascinating film, meanwhile, is Cruising (1980), which is most famous for negative things: the controversy provoked by its seemingly prurient and alarmist portrayal of New York’s gay S&M community, and the utterly mystifying storyline. (Even Friedkin admitted of what seems, superficially, like a straightforward serial-killer-investigation film, that “I myself was not sure whether there was one killer or more than one”). Still, for all its flaws, Cruising is in its own way as haunting and atmospheric as The Exorcist.

Among his other movies, The Brink’s Job (1978) remains a very watchable caper comedy, and The Boys in the Band (1970) a powerful if rather stagey drama. Like Cruising, it too was criticised for its portrayal of gay men (the play on which it was based just pre-dated Stonewall, and one protester is said to have described as “the best gay movie of 1947”).

Friedkin would also attract similar disapprobation over the treatment of Arabs and Muslims in his military-legal drama Rules of Engagement (2000), and indeed doesn’t seem to have gone to great lengths to avoid offence in his movies. Though this is more likely a case of simply not caring, or of unthinkingly confirming existing widespread stereotypes, rather than deliberately targeting any group. In Cruising, for example, one likely candidate for the killer is a gay man with daddy issues writing a thesis on musical theatre (about as stereotypical as one can get); and yet another gay man, Al Pacino’s neighbour Ted (Don Scardino), is the most sympathetic and realistic character in the entire film.

Over 20 movies and more than 50 years, Friedkin didn’t always hit the mark. Low points included The Hunted (2003), widely seen as a rehash of First Blood (1982); the erotic thriller Jade (1995), although Friedkin himself was fond of it; and The Guardian (1990), a horror exercise in which he revisited Exorcist territory a little.

Even these, though, can help to illustrate the persistent themes in his work. The US academic David Greven characterised Friedkin’s oeuvre as “an investigation of the ugly side of everything” and there’s some truth to that—look at the way he positively wallows in the nastiness of the South American locations in Sorcerer, for example, or the alien and disconcerting (to him and most of his audience) sexuality of the leather-clad bar orgies in Cruising.

It’s certainly true, too, that there’s a harshness, a bluntness, to his work. He didn’t shy away from violence, he was interested in evil and particularly the idea of infection, and of something wrong spreading its baleful influence. This can be seen all the way from The French Connection and, of course, The Exorcist, through to Cruising and Bug. Friedkin relished the conflict of apparent extremes: the church versus the devil, straight versus gay, police versus drug dealers.

And then there are particular types of scenes which seem to have appealed to him and recur repeatedly in his movies: assembling the gang in The Brink’s Job and Sorcerer (also The Exorcist, if you count Catholic priests as a gang), car chases in The French Connection, To Live and Die in L.A. and Jade, religious liturgy in The Exorcist and Jade, and so on. These similarities even extend to characters at times: there’s more in common between Gene Hackman in The French Connection and Pacino in Cruising than it might appear at first glance.

Above all, though, the former documentary maker was on a quest not for ugliness or evil or conflict as such, but for realism—seen in his preoccupation with detail, machinery, and the world of work. He was fascinated by the mechanics and minutiae of things. Blowing up a tree in Sorcerer, the words of exorcism in The Exorcist, the hanky code in Cruising, the telephone operator codes in The Boys in the Band, forgery in To Live and Die in L.A., the comparison of aphids and bedbugs in Bug, the Chinese gamblers in Jade, the slaughterhouse in The Brink’s Job… the list goes on and on.

Places were often similarly important to Friedkin: perhaps most obviously in Sorcerer, where the plot relies on the physical setting, but consider too the symbolic importance (and the contrast) of the Iraq-set prologue and the Georgetown house in The Exorcist, or the exoticism of Chinatown in Jade or the bars in Cruising.

Friedkin’s characters, on the other hand, were frequently undeveloped: not necessarily in the sense that they were cardboard cutouts, but one does get the impression he didn’t want to spend much time on them. Often, they consist primarily of their actions—in their jobs especially—rather than having believable independent existences, despite the comment by a character in Bug that the true self resides in an inner space.

Nearly always his principal characters are male, too, and women can get short shrift; until the end of Cruising, for example, Pacino’s girlfriend (Karen Allen) is important only as an indicator of his sexuality. We know almost nothing else about her except what she implies, or seems to imply, about him. It would have been fascinating, in this context, to see how Friedkin might have handled serial killer Myra Hindley in his unproduced film about the Moors Murders that he was working on in the late-1960s.

The typical Friedkin film—if there is one—is about men in a male milieu doing specific activities, examined in great detail. These may well involve danger, violence, and crime. Insanity and the randomness of fate might make an appearance too. Women aren’t likely to figure prominently (and to be fair, at least Friedkin also eschews token women; he may not have been the most inclusive of film-makers but his movies are never less than honest about where their interests lie).

Oh, and things will likely not end well.

All of this may sound Friedkin’s films sound bleak, yet in fact they’re not. Things don’t end well simply because things often don’t end well in the real world: the documentarian again?

Some of the directors he cited as influences in the documentary Friedkin Uncut (2018) might not be the ones you’d guess: Charlie Chaplin, Buster Keaton, Billy Wilder? But they all had a streak of fatalism which Friedkin shared, and though he could come across as humourless, there’s actually more wit than one might expect even in his non-comedies (though it’s also fair to say that’s not the flavour you’ll remember from them).

He loved John Huston’s The Treasure of the Sierra Madre (1948), too, a film which—devoid of women, unsparing in its depiction of the obsession that infects Humphrey Bogart, carefully portraying the technical intricacies of gold prospecting—bears clear resemblances to Friedkin’s own work.

There will be a Bogart connection to his final, posthumous film: The Caine Mutiny Court-Martial, starring Kiefer Sutherland and Jason Clarke in an updated version of Edward Dmytryk’s 1954 Bogart vehicle. It premiere at the Venice International Film Festival in September 2023. With the setting moved to the Persian Gulf in the present day, it’ll be interesting to see whether Friedkin takes any steps to remedy the offence he caused to Arabs and Muslims with Rules of Engagement.

Perhaps not, as tact doesn’t seem to have been a strong motivator for him. But it’s a pretty good bet the intricate details of courtroom procedure and naval law will figure prominently, and Monica Raymund (in the lead female role) less so.

After all, as La La Land (2016) director Damien Chazelle said in Friedkin Uncut: “He went in all these different directions yet he never made a movie that wasn’t a Friedkin movie, that didn’t have his stamp on it.” And despite the enduring fame of The Exorcist, that Friedkin stamp is much more about the detail than the devil.