CRUISING (1980)

A police detective goes undercover in the underground S&M gay subculture of New York City to catch a serial killer who is preying on gay men.

A police detective goes undercover in the underground S&M gay subculture of New York City to catch a serial killer who is preying on gay men.

In terms of controversial films of the late-20th-century, William Friedkin’s Cruising (1980) is in good company. It didn’t necessarily get as severe a reception as Martin Scorsese’s The Last Temptation of Christ (1988)—in other words, nobody firebombed a cinema for showing it—but it also didn’t get off as Salò; or the 120 Days of Sodom (1975), which only involved a couple of dozen countries banning it, some light police raiding, and one store owner being arrested for selling it on VHS 20-years later. Instead, Friedkin’s most notorious film was preceded by widespread protests from gay rights activists, followed by a mass shooting in one of the leather bars it prominently featured. While a direct connection between the shooting and Cruising was never established, the public consensus at the time was that the film’s exploration of New York City’s gay S&M sub-culture inspired the shooter.

This isn’t to say that the film had a death toll—no movie featuring Michael Corleone in full leather daddy attire could have that kind of power—but it certainly didn’t reflect well on Friedkin at the time. And the film’s legacy was inexorably stained for decades by its homophobic content and violent aftermath. All this would probably come as a surprise to an unassuming viewer in 2019, given that the film is, when viewed today, not more graphic than the average hard-R horror movie. Even more than that, though, it’s not really coherent enough to convincingly profess any kind of ideology—homophobic or otherwise. Critics and audiences at the time didn’t know what to make of it, which is completely understandable given that Friedkin clearly didn’t have a complete understanding of what he aspired to say and do in making this film. So, with that in mind, how does one watch Cruising in 2019?

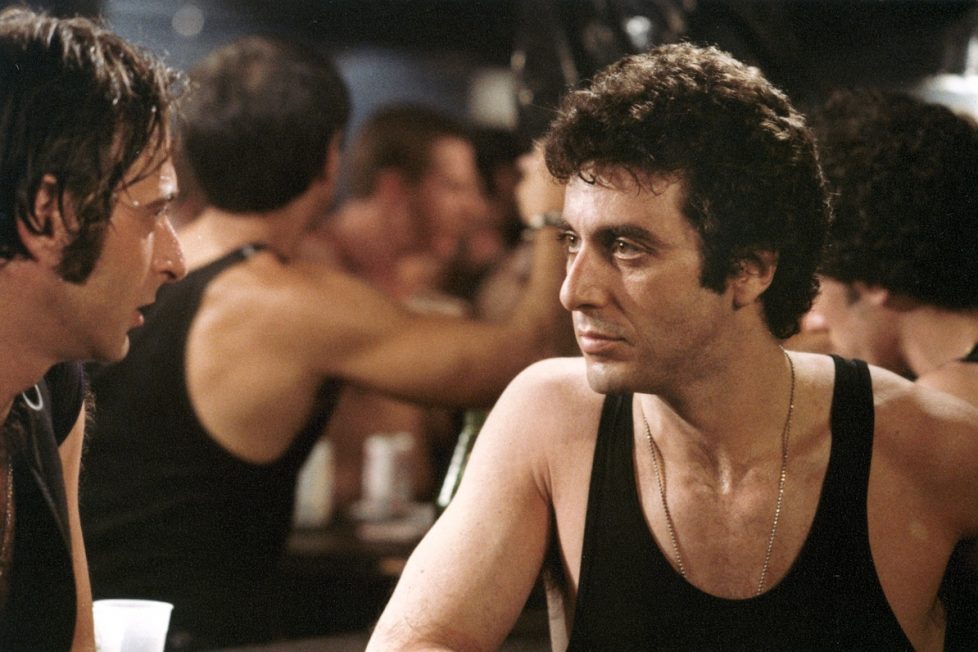

Do you read it as a psychological thriller-cum-horror, something entertaining that’s more interested in cheap thrills than big ideas? The film is, after all, not a far cry from the exploitation films and slashers that were coming into prominence at the turn of the decade. Steve Burns (Al Pacino) is an ordinary, pretenseless police detective assigned to go undercover in gay clubs around New York City to track down a homophobic serial killer. The victims are all a very distinctive type—thin gay men with curly, dark hair—and because Burns fits that profile, his role is essentially to be murder-bait and lure the killer into a one-on-one situation where he can apprehend him. This ends up translating as a number of scenes of Pacino dancing in leather bars, some surprisingly graphic gay sex, and some even more graphic murders.

That last part is where the slasher comparisons come in; the only significant variation on the slasher formula is that the victims are all gay men rather than straight women and teenagers. The truth is, sociopolitical context and historical significance aside, it’s pretty compelling as a straightforward stalk-n’-slash movie, appropriating plenty of motifs from films like Halloween (1978) and Abel Ferrara’s Driller Killer (1979), while also boasting some of the technical expertise Friedkin had exemplified in films like The Exorcist (1973) and The French Connection (1971). The combination of sleaze and technique is a potent one that makes the movie fun even in its more dated moments, and what Friedkin lacks in tact he makes up for in cinematic flair.

Of course, because it’s ultimately a slightly dressed-up exploitation flick, it deals in a lot of broadly sketched stereotypes, many of which are incredibly harmful and some of which border on absurdity. The idea of a closeted gay man murdering openly gay men out of shame lies in the former category; him having a comically large book on musical theatre in his apartment belongs to the latter. It doesn’t help that much of the film is spent watching gay men wander towards their demise like lemmings and that the deaths are always onscreen and as graphic as anything in Friday The 13th (1980). The visibility and bloodiness of these death scenes could mean one of two things: they’re either there for pure, adrenaline-pumping shock value…. or they exist to suggest these men are at least partially to blame for their own deaths.

If it’s the second option, then does that mean the film should instead be read as a diatribe—conscious on Friedkin’s part or otherwise—against the lives of promiscuous gay men? In most ways, the protesters had the right idea about the movie; in the grand tradition of exploitation cinema, it uses the leather bar subculture as a tool to shock audiences, rarely bothering to show the club patrons as anything but eccentrics and fetishists. If it doesn’t ever outright state that their sexual preferences are depraved, it certainly seems like it’s trying to get there. The murder victims are shown as people who seek out and find gratification in violence, which sends a pretty disturbing message when they’re shown getting dismembered for going home with the wrong man.

There’s an idea threaded through the movie that gayness is a costume one can put on and take off at will. Scenes of Pacino dancing in strobe-lit leather bars are consistently followed by scenes of him having rough, decidedly unsexy sex with his girlfriend—as if to remind us that him being undercover in these clubs doesn’t make him any less of a macho man. That gayness-as-costume idea is taken to its logical extreme when someone in a club asks Pacino if he’s a cop, before revealing that the club they’re in is police-themed and everyone there is roleplaying as either officers or criminals.

That idea and the aforementioned scenes do, unsurprisingly, elicit some unintentional laughter. This is a disturbing movie, no question, but it’s also occasionally a very campy one (see: every scene in which Al Pacino dances). Look no further than a later police interrogation scene featuring Pacino and a potential suspect. Mid-interrogation, a massive, Incredible Hulk-esque man wearing nothing but a cowboy hat and speedos bursts through the door. He strolls over to Pacino, not saying a word, and slaps him hard across the face. He walks out of the room, and the murder suspect yells “who was that!” He never gets an answer, nor do we, our only hint being a brief shot of that same lumbering cowboy outside the interrogation room smoking a cigar, suggesting he may have been a detective himself.

Of course, it’s dated for a different reason, too: Cruising was rendered antiquated within a year of its 1980 theatrical release thanks to AIDS officially becoming an epidemic in ’81, shifting the gay club culture of NYC dramatically. Beyond being a solid slasher and an unintentional homophobic manifesto, the film is underneath it all also a historical document of the Big Apple pre-AIDS.

It’s ironic that a film so clearly interested in exploitation rather than realism unwillingly became a landmark in the history of not only queer film but also New York City, but Cruising is hard to watch without thinking about the plague that followed it. By ’81 and perhaps even a little sooner, the cruising we see in these leather bars had fundamentally changed and the casualness of it had already begun to vanish, replaced by fear and anxieties about HIV and AIDS. Gay men being murdered one-by-one in the aftermath of casual sex feels like such an on-the-nose metaphor in hindsight, but Friedkin couldn’t possibly have known at the time that it would become a reality. Of course, because the murder victims are framed as at least partly to blame for their deaths, this retroactive reading also lends the film an even more homophobic subtext than it had in 1980. An interpretation I’m sure Friedkin wouldn’t want to touch with a ten-foot pole.

The truth is that Cruising is, in some ways, a better movie than its initial reception suggests. It unsettles, disorients, and disturbs in all the ways it intends to…. and, although it doesn’t quite have a point to it (and a movie this loaded with controversial ideas and imagery owes its audience some kind of message or raison d’être), it succeeds at making its viewers truly uncomfortable. The film is ultimately flawed and incomplete, though. It’s a long, tense buildup without any semblance of a satisfying conclusion. While movies like The Exorcist and The French Connection are self-contained, airtight works, this feels more like a rough draft for a great film. Friedkin has stated that his goal was to just make a straightforward murder-mystery set against the leather bar scene he was so fascinated by, one that avoids making any comment on the lifestyles of the gay people he depicts. Sometimes art gets away from the artist, because that’s not what he made, and the movie speaks to and encourages a lot of violent, hateful ideas about gay people.

Salò and The Last Temptation of Christ are controversial, confrontational films that employ difficult material to bring up difficult questions. They’re still part of the cultural conversation because their envelope-pushing was in service of a greater artistic purpose. Cruising doesn’t do anything nearly so noble, the deepest it ever gets being comparing the penetration of a stabbing to the penetration of sex—something that horror, as a genre, has explored more convincingly in the arts for decades, if not centuries. There’s room for a challenging, nuanced film about homophobic violence and its reverberation in the leather bar scene of the early-1980s, but this isn’t it. If you can stomach the frequently violent rhetoric (and content) of Cruising, there’s an engaging and tense horror-thriller at its heart. Look any deeper than that, though, and you will likely be left squirming for the wrong reasons.

director: William Friedkin.

writer: William Friedkin (based on the novel by Gerald Walker).

starring: Al Pacino, Paul Sorvino, Karen Allen, Richard Cox & Don Scardino.