10 RILLINGTON PLACE (1971)

A dramatised account of the real-life British serial killer John Christie and the man he framed for murder.

A dramatised account of the real-life British serial killer John Christie and the man he framed for murder.

If 10 Rillington Place is less brutally shocking today, that’s partly down to the five decades of increasingly baroque movie serial killers we’ve met since its release in 1971. And although the crimes committed by John Christie in the 1940s and 1950s are mundane by comparison with the excesses of Hannibal Lecter—set in a squalid, depressing post-war London world of bomb sites, cups of tea and poverty—Richard Attenborough’s mesmerising Christie has much in common with Lecter, so much so that it’s easy to believe Anthony Hopkins based his The Silence of the Lambs (1991) cannibal partly on the soft-spoken villain of 10 Rillington Place.

The film remains chilling largely because of Attenborough, but much of its power also comes from John Hurt in the other key role: Timothy Evans, the young man effectively framed by Christie for two of his murders, and hanged years before Christie’s true guilt was revealed. Indeed, from the filmmaker’s perspective, Evans is the centre of the movie.

It’s a cautionary tale about miscarriages of justice, and an anti-capital punishment polemic (albeit one appearing seven years after the last hanging in England, and five years after the posthumous pardon of Evans, whose case contributed to the abolition of judicial execution. This renders a common criticism of 10 Rillington Place—that it fails to provide any understanding of Christie’s motivations—somewhat beside the point. As Attenborough said:

I am passionately opposed to capital punishment, and when a private member’s bill was to be introduced in Parliament to bring it back, a number of chums said I should do something. They knew about the monstrous miscarriage of justice in the Christie case, and it became a cinematic protest against the death penalty. I do believe cinema has power.

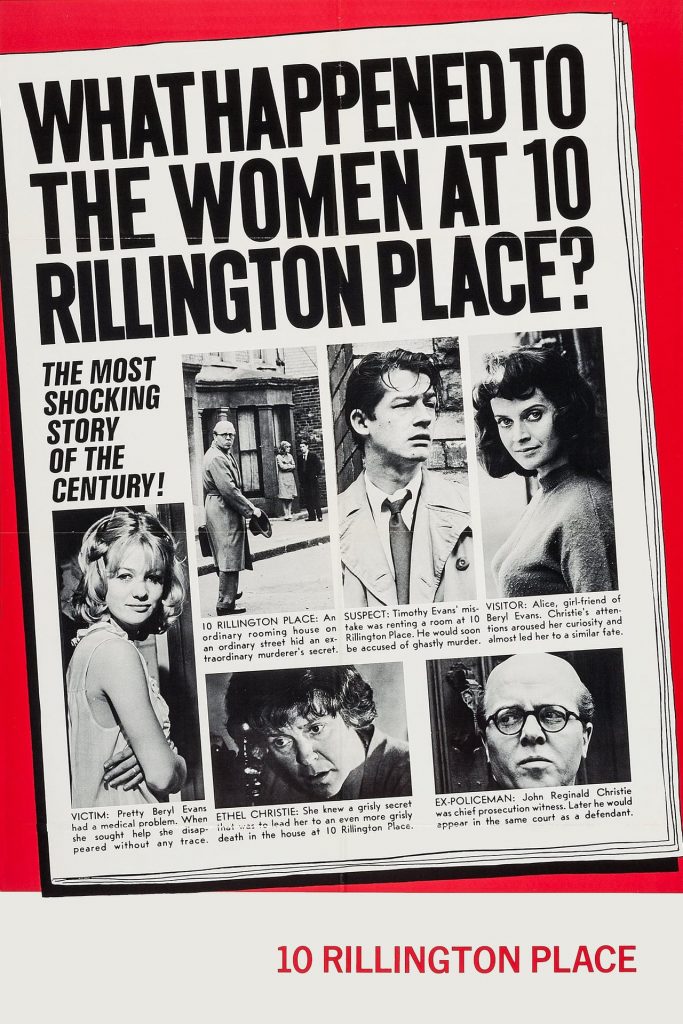

10 Rillington Place begins in 1944 with one of Christie’s earliest killings (an already-buried foot, appearing as he digs a hole in his garden to dispose of the latest body, cleverly indicating to us that it’s not his first). But the bulk of it takes place in 1949-50, getting going when Hurt’s Evans and his wife Beryl (Judy Geeson), along with their baby, rent rooms from the middle-aged Christie and his spouse (Pat Heywood). Their terraced house in Rillington Place, Notting Hill, west London is the setting for the horrors that follow.

When Beryl falls pregnant and the hard-up Evans’s panic at the prospect of another child, Christie—fond of claiming medical expertise—offers to perform an abortion, which was illegal at the time the story’s set. But it’s only a pretext to murder Beryl and, implicitly, molest her body.

Evans, distraught at the death of his wife during the “medical procedure”, is easily persuaded by a manipulative Christie to flee to Wales. Along with Evans’s hot temper, the couple’s frequent arguments, and his well-known habit of lying (to blokes in the pub about women, to everyone he meets about his job prospects), this only serves to make him look guilty. His subsequent confused tales to the police, and a slapdash investigation, only compound the problem. Evans is found guilty of murder and sentenced to death.

The film seems to run out of steam a little here, and its narration of the subsequent three years before Christie’s apprehension—during which he continued to kill women—can seem perfunctory today. But it’s also, in some ways, the most atmospheric section of the movie. With the live-wire Evans now absent, the claustrophobic gloom of Christie’s house, the increasing suspicions of his wife, and his decline into penury verge on horror.

Here, too, comes one of the most striking moments of the film, after Christie has sold all his furniture: he stands alone in the filthy house, and it’s as empty as his soul. (Although most of the interiors are studio sets, a few parts of the film were actually shot in Christie’s former home, and the exteriors show the genuine Rillington Place.)

The movie is largely carried by its two central characters, particularly Christie. Attenborough is impossible to forget: baby-faced and nearly bald, prissy at times and avuncular at others, polite except at the rare moments he lets his hate and arrogance show. He slinks around his domain on Rillington Place, peers cautiously through windows, stares at prey from behind his glasses with the eyes of an alligator, merciless.

His only real pleasure seems to be in pedantry, in pretended erudition: lecturing about “carbon monoxide, or CO2 as we call it”, invoking dubious legal impediments to prevent the Evanses going into his garden. And if he’s impossible to truly understand—when he examines himself in a mirror, we’re unsure if it’s vanity or terror he feels—that does nothing to diminish his sheer presence, made all the more powerful by the contrast between mild amiability and furious aggression. The line to Hannibal Lecter is clear (and to Tim Roth, who played Christie in similar fashion in the BBC’s 2016 three-parter Rillington Place).

Attenborough was at the height of his acting career when the film was made (its director, Richard Fleischer, had worked with him on the rather different Doctor Dolittle four years earlier). Hurt, who would receive his first BAFTA nomination for 10 Rillington Place, was closer to the beginning of his, but he delivers an Evans almost as memorable as Attenborough’s Christie, a nervous man inhabiting a confusing world who overcompensates with tall tales and fake confidence, then completely ceases to function when things get too stressful. (Evans, barely literate, was affected by what we would nowadays call learning difficulties.)

Few of the other cast stand out, although Geeson’s convincing as Beryl Evans, and Heywood underplays the part of Ethel Christie very astutely. She’s a woman in the shadow of her husband, doubtless exactly as he wants her to be, but there’s one magnificent moment where they’re standing in their small back yard with a group of policemen who’ve come to investigate “Evans’s” crime. She looks at Christie and the camera lingers on her stare just long enough for us to register that she knows.

For the most part, Fleischer’s directorial style suits the movie well. Versatile and prolific, he had just completed the Pearl Harbor epic Tora! Tora! Tora! (1970) and would shortly make the dystopian sci-fi classic Soylent Green (1973), but he also had several true-crime films to his name—notably Compulsion (1959), based on the Leopold and Loeb case, and The Boston Strangler (1968).

He and screenwriter Clive Exton (who based 10 Rillington Place on Ludovic Kennedy’s campaigning book of the same name, and had in 1970 also written a short London Weekend Television drama about Evans) needed to tread carefully. Although filmmakers had been seeking to make a Christie movie since 1962, the British Board of Film Censors (as it was then known) had resisted the commercialisation of such a recent and notorious case. It wasn’t until Fleischer and Exton came along that the board’s secretary, John Trevelyan, finally agreed to permit the production on the basis that it would “not exploit the revolting murders but should be a film that showed that even the best system of justice can make mistakes.”

As a result, 10 Rillington Place sticks close to established facts (an opening title comments that “whenever possible the dialogue has been based on official documents”) and rarely sensationalises. There are occasional flourishes that don’t sit comfortably with its generally straightforward tone—notably a cut from Evans plummeting on the gallows to Christie rearing up with back pain—but typically the visual manner of 10 Rillington Place is one of suggestion and allusion rather than overt drama.

Fleischer himself discussed the dilemma of explicitness in an interview with The Times:

Show too much and you run the risk of gratuitous sensationalism; show too little and you falsify the nature of the murderer. After all, it’s easy to feel compassion for Christie or the Boston Strangler if you never see what they actually did.

His solution is to show a little, but not much. Therefore, although the murder of Beryl’s a scene of detailed intensity, the sexual aspect of the first, pre-Evans killing that we see is conveyed by a single movement of Christie’s hand over his unconscious victim’s breast; the murder of the Evanses’ baby is condensed to a shot of Christie climbing the stairs.

The production design is similarly restrained (grey, brown, drab, although there is a bit more colour in Wales), as is John Dankworth’s score, which is queasy and disturbing in the few scenes where it’s heard.

10 Rillington Place appeared at a time when true-crime films had started to take off, many of them dealing with murders as nasty as Christie’s and some of them more vividly violent: Arthur Penn’s Bonnie and Clyde (1967), Richard Brooks’s In Cold Blood (1967), and Fleischer’s own The Boston Strangler would have been fresh in the public’s minds. Indeed, awareness of the concept of serial killing and the related film genre date from around this point, though of course both the crimes and the movies had been around a lot longer—on-screen, from Hitchcock’s The Lodger (1926) right up to his Psycho (1960) and beyond.

To some, 10 Rillington Place felt unduly restrained and, frankly, uninteresting in the context of late-1960s and early-1970s cinematic homicide. While both Attenborough and Hurt were widely praised for their performances, the opinion of Vincent Canby in The New York Times was typical:

…a solemn, earnest polemic of a movie, one with very little vulgar suspense [which] carries very little dramatic conviction, and evokes hardly any emotion except the one relating to the barbarity of capital punishment—which is not enough to sustain this sort of entertainment enterprise. The problem with the film is very much the problem with the actual case, which involved small, unimaginative people in some sordid events, and which became interesting and significant only in its ultimate ramifications. Christie was a mass murderer, all right, but a very dull one.

There’s some truth to this criticism. As 10 Rillington Place so diligently stuck to the facts, Evans’s plight is never emotionally distressing, even if we understand intellectually why it’s so wrong. Despite Hurt’s terrific performance, he’s still more a case study in victimhood than a character to be empathised with. (It’s interesting that we feel far more for the Diana Dors character facing execution in the similarly polemical Yield to the Night, even though she is guilty.)

But if this means it fails slightly in its goal of provoking revulsion at capital punishment, it’s still a disquieting film, much of its effect coming from mood rather than any particular incident. The world of 10 Rillington Place is a joyless one where most things are sour, dominated by Attenborough’s monstrous Christie, all the more terrifying because he remains unexplained.

And in this respect, although it never employs the language of horror, it turns out to be as much a horror movie as the more extravagantly sadistic serial-killer sagas that arrived in subsequent decades.

UK | 1971 | 111 MINUTES | 1.85:1 | COLOUR | ENGLISH

director: Richard Fleischer.

writer: Clive Exton (based on ‘Ten Rillington Place’ by Ludovic Kennedy).

starring: Richard Attenborough, Judy Geeson, John Hurt & Pat Heywood.