John Hurt: Imagination’s Victim

I cannot say enough good things about John Hurt. What he did is just glorious. His character is so fantastic. It’s a human-being thing; your heart just goes out to him for what he went through.

That’s director David Lynch reflecting on The Elephant Man (1980) for Time Out magazine in 2008, and it’s a fitting description of Sir John Hurt, who passed away on 25 January 2017, and his remarkable life. Hurt’s extraordinary performance as John Merrick in Lynch’s film was one of many in a career that saw him progress from an interesting, challenging young performer, into a beloved, hard-working, reliable British actor immediately identified by his mellifluous voice.

Born in Chesterfield, Derbyshire in 1940, John Hurt’s future career was clearly influenced by his mother, who was an amateur actress when she wasn’t busy being an engineer. Sadly, Hurt endured an isolated and disturbed childhood. Despite having a cinema on their doorstep, his parents didn’t allow him to go and watch films, and he was kept away from interacting with local children.

He also endured the misery of abuse at the hands of a senior master at St. Michael’s Preparatory School in Kent, and developed an interest in acting as a coping mechanism. As a boarder, he gave his first stage performance at school, telling Shortlist in 2016:

… when I was nine, I was doing a Maeterlinck play called The Blue Bird—playing the girl. I was always playing girls because I was very small, and quite pretty, and had rather a high voice. I was suffused with the knowledge that I was in the right place. I can’t put it any other way. It was just absolutely clear as a bell. It was the first formal play I’d done in front of an audience that was organised.

His parents loved the theatre and he often accompanied his mother to regular performances at Cleethorpes Repertory Theatre when, at the age of 12, his family moved to Grimsby. An equally unhappy boarder at Christ’s Hospital School in Lincoln, he appeared as Lady Bracknell in a school production of The Importance of Being Earnest. However, his headmaster told him he “wouldn’t stand a chance in the acting profession” and his parents resolutely dissuaded him from pursuing a career as an actor. “The two things that were required after the war was security and respectability. Acting didn’t offer either of them. So the only other thing I could do was drawing and painting. You could teach that. Nobody taught drama,” he recalled in 2016.

Hurt was pushed into studying painting at Grimsby Art School, and in 1959 he won a scholarship to study at Central Saint Martins in London. Desperately short of money, he would ask his friends to pose for him and then sell the paintings. Unbeknownst to Hurt at the time, one of the models that posed nude for the art students was Quentin Crisp. Crisp would have a profound effect on his future success as an actor, a passion that he was able to finally realise with a RADA scholarship in 1960.

Perhaps Hurt’s repressed childhood held the key to his unique way of subtly externalising the internal turmoil of the memorable characters he went on to play. As critic Danny Peary succinctly summarised, he had a mesmerising ability “to be deep in thought; his characters’ sexual natures are often thematically central to Hurt’s films. He specialises in effeminate men, superior-acting decadent men, sadistic killers, and victims.”

After a number of theatre and television credits in the early 1960s, his film debut was at the age of 22 in Ralph Thomas’s angry young student drama The Wild and the Willing (1962). He picked up good notices and a £3,000 salary for his role as the power hungry Richard Rich, who was rewarded with the position of Solicitor General by Thomas Cromwell for his betrayal of Thomas More, in Fred Zinneman’s A Man for all Seasons (1966). It was an early example of Hurt portraying a weak man swayed by corruption despite receiving prudent advice from More (Paul Scofield) that “a man should go where he won’t be tempted.” Hurt captures particularly well the loss of innocence and failure of conscience in the tainted humanity of Richard Rich.

Similarly, he was praised for his sympathetic portrayal of the falsely accused Timothy Evans in 10 Rillington Place (1971), Richard Fleischer’s disturbing docudrama about serial killer John Reginald Christie. Hurt instinctively conveyed the naivety and bewilderment of this illiterate, innocent young man manipulated by the coldly intelligent Christie, brilliantly played by Richard Attenborough. He was nominated for a Best Supporting Actor BAFTA in an affecting film about capital punishment and the tragic mistakes that can result from wrongful convictions.

In the same year, he took on the lead role in Mr. Forbush and the Penguins, a flawed gem of a British film. Initially, Hurt had to be persuaded not to walk off the troubled production when the original director and his female co-star were replaced.

Hurt imbues the spoilt, rakish, self-absorbed biologist Richard Forbush with an appealing energy and humanity. When his philandering ways and dubious charms are rejected by Tara (Hayley Mills), Forbush, wondering how he can impress her, retreats to the Antarctic on a six month research project to monitor penguins during the mating season. He is gradually transformed by the power and wonder of nature, battling through blizzards and defending penguin chicks from skua attacks, into a humbler, more sympathetic human being.

In anyone else’s hands this would simply be risible cliché, but Hurt is a triumph. Despite some beautiful location work, it’s a film that has its technical deficiencies, but Hurt is compelling and expertly unearths the humility within the narcissistic Forbush.

The film adaptation of David Halliwell’s Little Malcolm and His Struggle Against the Eunuchs (1974) is another underrated entry in the Hurt canon. It allowed him to tap into his experience at Central Saint Martins with his acerbic portrayal of Malcolm Scrawdyke, an art student who plots revenge after his humiliating ejection from college. It’s a film about frustrated political will and sexual impotence, and Hurt’s character has a Hitler-like charismatic control over his three misbegotten recruits Wick (John McEnery), Nipple (David Warner), and Irwin (Raymond Platt). They form the Party of Dynamic Erection and he plots political revenge against an unseen art college lecturer, Allard. Allard becomes a representation of the ‘eunuchs’, the conformist mass of society against whom Malcolm constantly rails in order to prove his masculine potency.

It’s a witty, surreal parody of the clash between art students and higher education institutions, with their perceived deficiencies of art education that often led to demonstrations and occupations of university and college buildings in the 1970s. A provocative and playful satire that examines power, gender and fantasy, Hurt, McEnery, and Warner are utterly hilarious and terrifying as the larger-than-life trio of characters.

As well as further roles in film, including The Ghoul (1974) where he played Peter Cushing’s feral handyman, it was television that made him a household name in the mid-1970s. He made appearances in such diverse fare as The Sweeney, Wessex Tales, and Play for Today. Two memorable roles cemented his reputation: one would reunite him with his legendary artists’ model Quentin Crisp for The Naked Civil Servant (1975), and the other would offer an essay in evil as notorious Roman emperor Caligula in the BBC’s I, Claudius (1976). Playing “one of the stately homos of England” and “the greatest god of all” within the span of a year had a huge impact on a generation of young teenagers, of which I was one at the time. For me, Hurt was one of the first actors, whose conviction in both roles offered a genuine revelation of the power of acting to receptive young minds.

In Jack Gold’s superb The Naked Civil Servant his interpretation of effeminate homosexual Quentin Crisp’s flamboyant voyage from youth to middle age poignantly chronicled a post-war society dominated by prejudice and intolerance. It lifted the veil for many about the oppression and homophobia faced by gay men and for many curious, potentially closeted teenagers, Hurt’s nuanced performance provided a startling moment of self-awareness. His beautiful, sensitive portrayal honoured Crisp’s pride, humanity, wit, wisdom, and sheer determination. He deservedly won the BAFTA for Best Actor in 1976.

Crisp stayed with him through his career and he told Gay Times in 2009:

… he [Crisp] stands for a lot. He’s somebody capable of changing lives, and any such character is going to be endlessly, limitlessly interesting.

Although he initially had his doubts he agreed to return to the part in 2009 on the strength of Brian Fillis’s script for An Englishman in New York. Richard Laxton’s film centred on a 72-year-old Crisp’s arrival in New York, his status as one of its resident aliens and his self-created shibboleths of describing AIDS as “a fad” and the urgent need to be the centre of attention, even though ill heath and age sought to prevent it.

It’s a moving glimpse into Crisp’s decline into debilitating old age and the generational conflicts within the gay community itself. The doubt and guilt are etched on Hurt’s face and that feeling of being ‘not wanted on voyage’ pulsates and aches from the screen and is a heartfelt reminder of the importance of being yourself even when it isn’t fashionable to be so.

Back in 1976, Hurt originally turned down the role of Caligula in I, Claudius, but director Herbert Wise cannily invited him to a BBC pre-production party and, when he met many of the celebrated ensemble cast, he changed his mind. Hurt reportedly had to dig deep inside his imagination to bring the sociopath Emperor to spectacular life.

This was a man who proclaimed himself a God, appointed a horse as a Roman senator, had a child’s head cut off because its coughing irritated him, and removed the foetus of his future heir from his sister’s womb. Speaking to the New York Daily News in 1991, Hurt said of his role:

Caligula is the method actor’s nightmare… you can’t identify with Caligula at all. Therefore, you have to rely entirely on your imagination. I don’t doubt for a moment he was congenitally mad, but I played him as though in his view he was sane—a regular guy.

By dint of this, Hurt invested Caligula with a tragic self-awareness that ensured his outrageous villainy was grounded by an internal truth. He managed to find a hint of humanity beneath the debauchery.

On the back of his newfound respectability, Hurt turned in several exceptional film performances as the 1970s gave way to the 1980s. He picked up a Best Supporting Actor BAFTA for his role in Midnight Express (1978) as Max, the opium-addicted inmate sharing the deprivations of an Istanbul prison with Billy Hayes (Brad Davis), an American student arrested for drug smuggling.

It was a difficult shoot, made more so by director Alan Parker’s penchant for not suffering actors gladly. Actors were kept from reviewing the dailies and from crew-only parties. Hurt and his co-stars, annoyed at this treatment, set out to wreak revenge. For his part, Hurt hired a gaggle of local prostitutes to crash one of the cliquey gatherings.

1978 was a very good year. Hurt loaned his instantly recognisable voice to animated films Watership Down and The Lord of the Rings, and turned in a intensely understated supporting role in The Shout battling Alan Bates and his terrifying Aboriginal shamanistic shout. The film is a clash, both physically and ideologically, between Hurt’s self-indulgent, weak bourgeois Anthony, and Bates’s raw, animalistic, immoral Crossley, and is a surreal, poetic, and bleak exploration of loneliness and madness.

His signature appearance in Ridley Scott’s Alien (1979) really needs no further embellishment, except to say he was happy to send himself up with great aplomb in a skit of his alien birthing for Mel Brooks’s Spaceballs (1987).

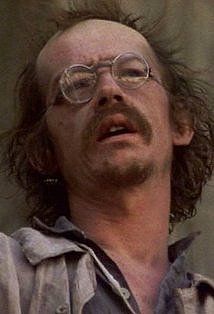

A mention of Mel Brooks brings us back to Hurt’s iconic performance in The Elephant Man (1980). Brooks gambled on David Lynch to direct the film after he saw Eraserhead (1976) and Hurt was already being considered for the role of Joseph Merrick, a severely deformed man who endured the cruelties of Victorian society but refused to give in to despair and abandon his dignity. Surgeon Frederick Treves (played by Anthony Hopkins) eventually rescued Merrick from his terrible life as a sideshow freak and brought him to live at the London Hospital.

Producer Jonathan Sanger recalled Lynch was thinking of Eraserhead’s Jack Nance to play Merrick “but once he saw John in The Naked Civil Servant, he was convinced.” Hurt met Brooks in a meeting room full of life-size photographic murals of the real Joseph Merrick and, according to Sanger:

John came in and sat down and we never referred to the photographs but John kept looking up at the pictures and eventually we had to tell him this was the character we wanted him to play. By the time the meeting was over, he wanted to do it.

Hurt’s challenge was to project the renamed John Merrick’s humanity through the many layers of Christopher Tucker’s makeup, a sixteen-piece application process Tucker managed to reduce from 12 to 8 hours. His worries that the crew would laugh at him were dispelled when Hurt made his first appearance on set and co-star Anthony Hopkins confirmed, “it’s going to work. It’s going to be a great movie.”

Hurt went to watch the dailies only once during production:

There was no point. With all that makeup on I couldn’t be sure what I was doing. I had to rely totally on our director… at one point I became very depressed and felt nothing I was doing was coming through on screen.

As it turned out, it was a beautifully made film with Hurt’s sensitive and intelligent physical and vocal performance gaining him an Oscar nomination.

He continued to work during the 1980s and 1990s. He made an excellent and perhaps definitive Winston Smith in Michael Radford’s bleak and bitter Nineteen Eighty-Four (1984), was suitably world-weary as professional killer Braddock in stylish, witty British crime thriller The Hit (1984), and captured the inevitable tragedy of Stephen Ward in Profumo drama Scandal (1989).

Of all his ’90s films, I would highly recommend Love and Death on Long Island (1997) for Hurt’s quiet, gently amusing, tender performance as dusty academic writer Giles De’Ath who, one rainy afternoon, wanders into the wrong cinema to catch an E.M Forster adaptation and becomes infatuated with teen idol Ronnie Bostock (Jason Priestley), appearing in the luridly titled “Hot Pants College II”.

The infatuation leads to De’Ath suddenly discovering the modern world, where the pleasure of renting videos and seeing films featuring Ronnie leads to him tracking down the object of his unrequited love in Long Island, New York. Giles eventually inveigles his way into the home of Ronnie and his girlfriend Audrey (Fiona Loewi). On the pretext of remaining in Ronnie’s company, Giles offers to write a new film script for him. When Giles eventually pledges to devote the rest of his life to Ronnie, the dance of love comes to an end and Ronnie departs. Giles, brokenhearted, is left to explain his infatuation to Ronnie via an epic fax communication.

It’s a tender, bittersweet, and witty film, expertly adapting Gilbert Adair’s short novel (itself a comic spin on Thomas Mann’s Death in Venice), where the quiet, considered interplay between Hurt, Priestley, and Loewi reveals the humanity and romance in this mediation on unrequited homoerotic love, the thin veil between stardom and reality, the transfiguration of loneliness through the power of creativity. Hurt is rather magnificent.

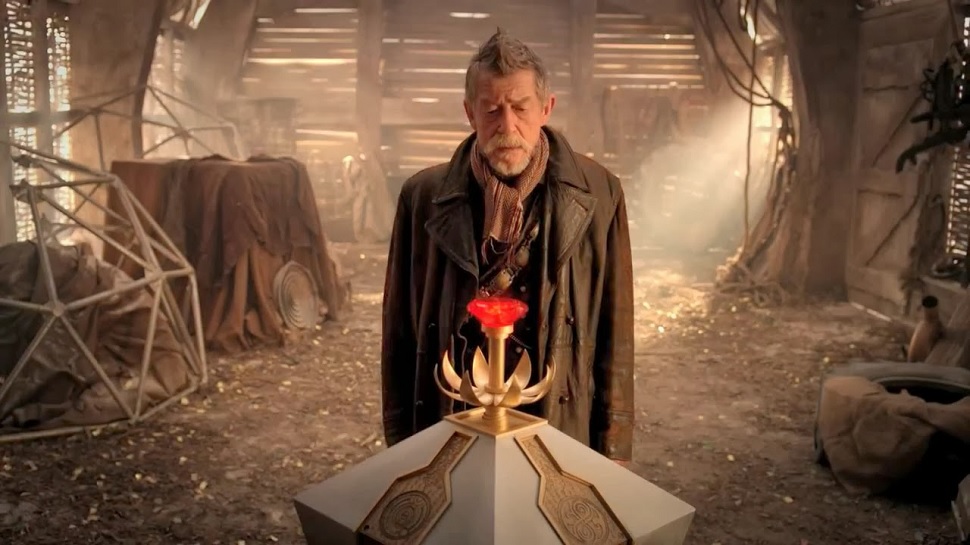

His wildly varied film and television portfolio continued to expand, appearing in or lending his vocal talents to Contact (1997), Hellboy (2004), The Alan Clarke Diaries (2004), the Harry Potter franchise between 2001 and 2005, V for Vendetta (2005), Indiana Jones and the Kingdom of the Crystal Skull (2008), and the voice of the wise dragon in BBC TV’s Merlin (2008–12). He stood out as the steely Control in Tinker, Tailor, Soldier, Spy (2011) and was immortalised for fans of a certain Time Lord as the ‘War Doctor’ in Doctor Who’s 50th anniversary special “The Day of the Doctor” (2013). Narration, pop videos, and video games were all equally within his talented remit.

His cancer diagnosis in 2015 didn’t slow him down, and he was still making films up until his death. He can be seen in current release Jackie (2016) alongside Natalie Portman as Jackie Kennedy’s confidante priest Father Richard McSorley. Its director Pablo Larrain recently paid tribute and said: “John was invincible. Unflinching. Eternal.” Quite rightly, he’s been lauded as a unique talent and saluted for his wonderfully diverse career. One would hope that, like Joseph Merrick, his life was full because he knew he was loved.

I am really the victim of other people’s imaginations—John Hurt (1940-2017)