TAKE BACK THE NIGHT (2021)

A young woman attacked in a Los Angeles alleyway insists her assailant was a monster... literally.

A young woman attacked in a Los Angeles alleyway insists her assailant was a monster... literally.

Yes, Jane (Emma Fitzpatrick) admits to the police detective handling her report of an assault that she was drinking and taking drugs before venturing out into the deserted night-time streets where she was attacked. Yes, we realise as the detective (Jennifer Lafleur) continues her investigation, there are inconsistencies in timing and location in Jane’s story. And yes, the throngs of women commenting online to confirm Jane’s belief that she was assaulted by an actual, not merely metaphorical, monster could easily be conspiracy theory kooks.

However, in Gia Elliot’s feature debut Take Back the Night, Jane’s experience is also depicted so rawly, intensely and horribly that it’s impossible not to believe her on a visceral level, despite all the rational reasons for doubt (including the presumed non-existence of monsters). It’s difficult to be sure exactly what if anything Elliot (who has also worked as Gia Vangieri) is suggesting to the audience in terms of objective truth, but very likely looking for a literal reality in Take Back the Night is a mistake anyway. It’s not the point.

In Elliot’s film (the title of which refers to the international organisation concerned with violence against women, not the Justin Timberlake song) it doesn’t ultimately matter all that much whether a pitch-black stinking demon did emerge from behind a dumpster and brutalise Jane, or whether a man did, or whether the complete truth will remain inaccessible both to the characters and to the audience. What matters is that Jane is so widely and dismissively doubted, and turned into a guilty party rather than a victim; Elliot’s movie is not so much about the crime of rape itself as about the subsequent experience of women who report it. The point is not the monster but Jane, her full name—Jane Doe—overtly casting her as Everywoman.

Structurally the film is simple. Here, as in the occasionally didactic dialogue, Elliot (and Fitzpatrick, who co-wrote as well as playing Jane) evidently didn’t want anything to get in the way of the message. After a brief and deliberately misleading dive into the middle of the story illustrating how emotionally devastated Jane has been by reactions to her report of the assault, it starts at the beginning.

Jane, an artist and social media influencer, is at a gallery party where she drinks, takes an unidentified pill, and has random sex in the bathroom—all things, of course, which are supposed to somehow make women “responsible” for being raped. (Later, in a sequence which would almost be funny if it weren’t so grim, the same “responsibility” is alluded to in a scene where Jane changes her car tire in a deserted area in the middle of the night, wearing the skimpiest of short shorts.)

At the party, Jane helps another drunk woman outside, then finds she can’t get back into the building, so she sets off to walk home. But there is odd scuffling and growling around her, hordes of flies appear from nowhere, and then the monster strikes: a genuinely terrifying thing more glimpsed than seen, rather reminiscent of Charles Keeping’s M.R James illustrations, eyes glowing furiously through the fuzzy outlines of its body.

The attack is vicious, and Jane’s injuries—odd carvings and slices as well as the more expected scrapes and bruises—are depicted in painful detail; her examination soon after at a hospital seems almost as intrusive as the violence, too. Yet it’s only a foretaste of the even harsher mental and emotional onslaught she’ll suffer from the media, from the online public (“attention whore”, one commenter calls her), from her well-intentioned but more conservative sister (Angela Gulner) anxiously pushing her toward therapy or even commitment in an institution, and from the detective who’s initially sympathetic but also comes to doubt Jane’s story.

For a long time her case is treated as a straightforward sexual assault, and when Jane says things like “the monster that did this to me is still out there” it’s assumed to be a figure of speech. It’s relatively late in the film when Jane confirms there is, indeed, a reason to believe in actual monsters attacking women. Even then, however, it seems only those who’ve encountered them are prepared to accept their existence. “Please don’t say the word ‘monster’ on national television,” Jane’s sister pleads.

Though the final act is a bit over-protracted—Elliot and Fitzpatrick don’t seem entirely sure how to end the film, and one plot development feels like it’s there only to justify a humdinger of a “no means no” line—for most of its runtime Take Back the Night moves briskly forward. It’s certainly not superficial, it’s thoughtful, but the film is firmly focused on its main storyline without digressing into subplots. It’s artfully constructed too: Jane’s live-streamed social media commentary, for example, is a successful way of adding both depth and momentum to solo scenes which could otherwise flag.

Apart from a small role for Sibongile Mlambo as the detective’s girlfriend, there are no characters of any importance beyond Jane, her sister and the detective, and the movie benefits greatly from convincing and rounded performances in all these roles.

Fitzpatrick wisely doesn’t try to persuade us to identify too closely with Jane, a rather abrasive woman, or imbue her with some spurious victim-sanctity; she doesn’t have to be an angel to deserve better than she gets. Gulner similarly avoids stereotyping the sister, who is simultaneously easy to like and decidedly annoying, while Lafleur’s detective is neither too noble to be true nor a mere symbol of bureaucratic callousness. Though Jane is the character who dominates, in some ways the detective is just as important a key to the film: her reaction to Jane’s fantastic story stands for ours.

Technically, meanwhile, Take Back the Night—five years in the making—stands head and shoulders above the average lower-budget horror movie. While sets, locations, and costumes feel realistic, Elliot’s own cinematography with its extremes of colour grading (a jaundiced yellow as Jane leaves the party, for example) often adds a not-quite-real air appropriate to the uncertainties of the narrative.

There are some effective and brief flashbacks or hallucinations, and skilful editing by David Elliot (also the production designer) from the first party sequence on. Another strong complement to Jane’s story comes from Chris White’s original score, frequently distant, rumbling, and disturbing. One of its best passages is heard in a subway station scene, where the music could almost be the rattling of a train.

“All official answers must be limited to yes or no,” an unseen speaker declares in the very first line of Take Back the Night. It soon becomes apparent that they are talking about a polygraph test, but they could equally be referring to Jane’s plight, caught in a system where only absolute, demonstrable facts are acceptable evidence.

Of course, facts do exist independently of what we think we know. Lived experience is not everything, and Take Back the Night does seem to leave deliberately open the question of how much Jane’s perceived experience correlates with the objective fact.

Just how open this question seems to be may also reflect how far viewers themselves trust Jane. And it is interesting that Elliot, on the audio commentary, relates that while she originally chose to have a monster rather than a human villain in order to focus on the survivor and avoid questions about the perpetrator’s motivation, she ended up giving it a much fuller back story than the film reveals—implying that to the filmmakers, the monster is more definitely real than it might be to the audience.

But there’s no need to dwell on this too hard, for objective truth, “what really happened”, is not the main concern of Take Back the Night. It presents, for the most part powerfully despite some slight weakening toward the end and occasional moments of obviousness, a passionate case for listening to experience too, a case for not automatically doubting, and above all for not turning the wronged into the wrongdoer. Whatever took place outside that party, Jane is not the monster here, and Take Back the Night is a strikingly original, forceful plea that we listen to Jane Doe’s everywhere. It’s a film that will not be easy to forget.

USA | 2021 | 90 MINUTES | 1.85:1 | COLOUR | ENGLISH

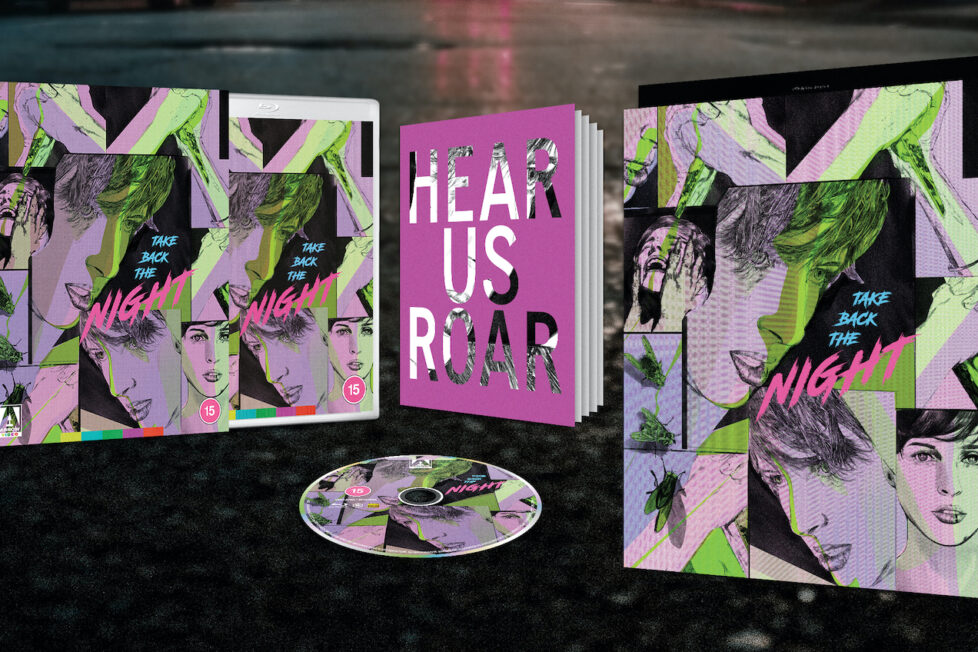

For this Blu-ray release, Arrow Video has assembled an impressive collection of extras mostly related to the film’s central concern of violence against women. From a technical standpoint, our review disc was very quiet, but otherwise both video and audio were impeccable.

director: Gia Elliot.

writers: Gia Elliot & Emma Fitzpatrick.

starring: Emma Fitzpatrick, Angela Gulner, Jennifer Lafleur & Sibongile Mlambo.