BLOW OUT (1981)

A movie sound recordist accidentally records the evidence that proves that a car accident was actually murder and consequently finds himself in danger.

A movie sound recordist accidentally records the evidence that proves that a car accident was actually murder and consequently finds himself in danger.

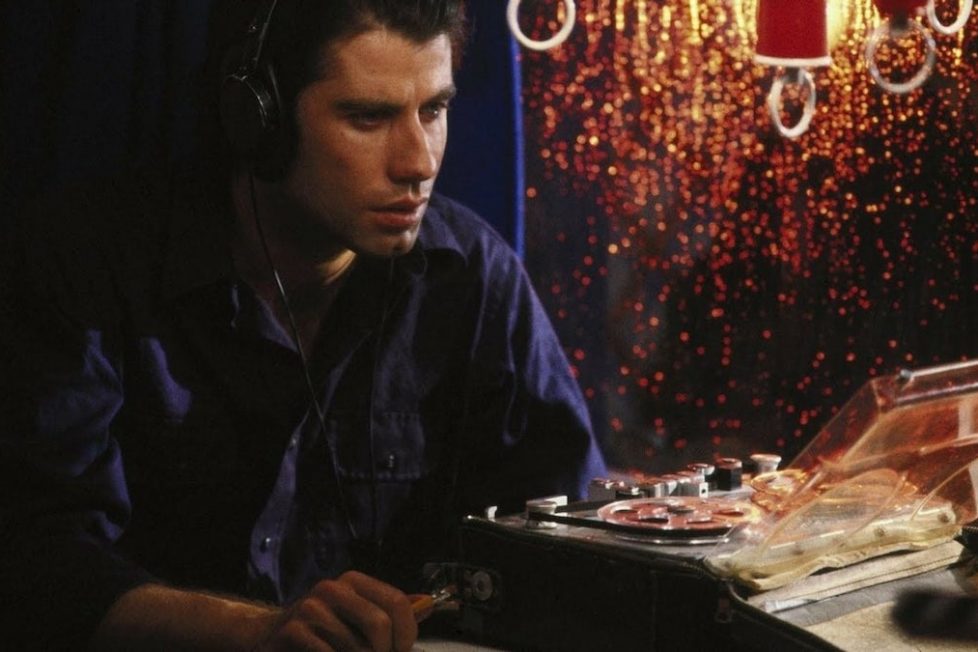

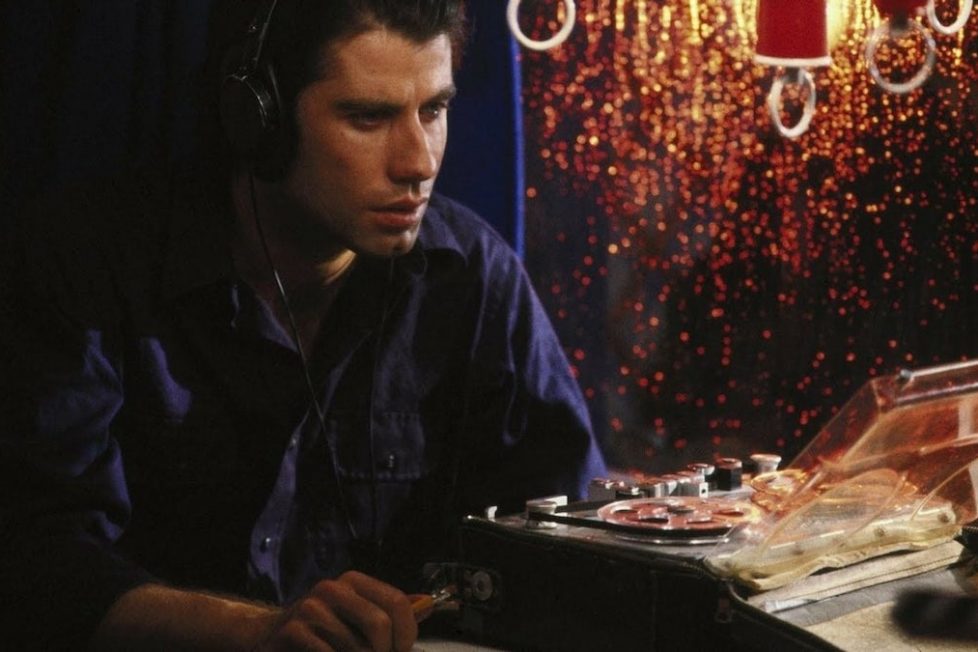

Jack Terry (John Travolta) is a sound engineer for schlocky horror films. When the director of his latest picture is unhappy with the library sounds he’s using, Jack heads out into the night to capture fresh ones… and as his audio tape’s running, a nearby car’s tyre bursts, sending the vehicle off a bridge into a river. He dives in and saves a passenger (Nancy Allen) from the back, but is unable to save the unconscious driver. At the hospital, he learns the driver was a popular governor, expected to run for president and win. He tells the police he definitely heard a shot before the tyre blew out, and has the tapes to prove it… which is a big mistake, as now both he and the woman become the target of those behind the assassination…

As the lead, Travolta brings his usual edgy presence. It’s an inspired piece of casting because he’s exactly like the slightly slimy people who work in low-budget ‘tits and gore’ films, and he’s also not someone you’d believe if he claimed a politician’s car accident was actually an assassination ordered as part of a shadowy conspiracy. Travolta sells the desperation of the character, and the emotional gut punch of the ending. Even if the last thing he does in the story (no spoilers, but “using the scream” should be enough for those who have seen the film to know what I mean) makes no emotional sense for the character, and is clearly only there because it appealed to writer-director Brian De Palma’s perverted sensibilities.

Indeed, his performance makes you wish Travolta had been given more of these roles at the time. He seemed to go from hot young thing to has-been overnight in the 1980s, then Quentin Tarantino brought him back for Pulp Fiction (1994), which set him up for a decade of madcap villains. It’s a shame, because he could’ve had the eclectic career of a Nicolas Cage or a Jeff Goldblum, but it sadly wasn’t to be. It must be said, however—and you’ll read this word a few times in my review–that Travolta’s character is rather stupid. He doesn’t make multiple copies of his crucial tape, and he doesn’t just send the damn thing to The Washington Post or CNN. He’s also a terrible driver. It diminishes the suspense of the film, just as it does in horror movies, when characters consistently refuse to do the simplest and smartest thing to save their lives.

Nancy Allen (Carrie) gives a perfectly decent performance in a role that feels so regressive it could’ve come out of the black-and-white era. Although, in the Golden Age she wouldn’t have got naked, so maybe it’s even worse. Sally’s primarily income is from being the honey in a trap, getting caught on camera, and getting a share of the blackmail money. She’s also as thick as two extra-thick planks stuck together with stupid glue. Seriously, it’s a wonder she can dress herself. Freud could probably make something of the fact De Palma wrote this kind of role for his wife—again. As it is, Sally does almost nothing and she’s just there to be put in danger. In fact, she isn’t so much put in danger, as go walking merrily into danger whistling a happy tune. In supporting roles we also get solid performers like John Lithgow and Dennis Franz, and they also do a decent job with what they have…. but for some reason they’re not forced to strip down to their underwear. I can’t fathom why.

But all performances in a De Palma movie come second to the filmmaking. And what beautiful filmmaking it is! Let’s face it, nobody watches Blow Out, Dressed to Kill (1980), or Body Double (1984) for the storyline or performances. Film nerds watch them for the high-angle shots, the ‘oners’, and most of all for the split diopter. At the time, I imagine people also watched them for the bare flesh (again, that’s female flesh only, unless you count Franz’s hairy arms). De Palma is a consummate film technician, and one can tell he’s far more passionate about Jack’s job as a sound engineer than anything else—revelling in the details of his process—than he is about the conspiracy storyline, which couldn’t be more generic.

And, so, it’s time to ask the difficult question: what can we learn about De Palma from his films? He loves Alfred Hitchcock, that much is obvious. Perhaps the most overt reference is Lithgow waiting for a prostitute to finish brushing her teeth before he lowers his garotte round her throat, just as Anthony Dawson has to wait for Grace Kelly to hang up the phone before he can strangle her with a knotted stocking in Dial M for Murder (1954). What else? He loves a split diopter, we all know that. He uses it all the time; sometimes subtly, and sometimes he uses it so an owl can look directly into the camera with an expression exuding more intelligence than Nancy Allen’s character and more self-awareness than De Palma. Oh, and he’s a misogynist, that’s also clear. There’s a line in the film when Lithgow’s assassin says to his masters that he’s decided to kill Sally and “make it look like a series of sex murders in the local area.” Well, of course he has, because this is a De Palma move, what would one be without a few sex murders? (Don’t say “a Hitchcock movie”). This may be controversial to say, but I think it’s always a bad sign when you can imagine the filmmaker vigorously masturbating to what’s on screen.

His misogyny is probably best demonstrated in the opening sequence, which is De Palma’s take on a stalking killer scene from a cheap horror movie. The specific reference is Halloween (1978), a vastly superior film, even if De Palma didn’t like it, and it’s knockoffs. There are coeds dancing in flouncy underwear, a topless woman having sex, a woman masturbating, and another in the shower, and what’s most revealing about this section is the only thing that differentiates it from the rest of the film is how bad the filmmaking is. Not the exploitation, because we get that throughout the “real” film, and audiences got it throughout Dressed to Kill the year before. You can imagine De Palma shouting to the audience “look how terrible this film is!” and them agreeing, only for De Palma to add, “I mean, look how wobbly the Steadicam is!” But, truthfully… the filmmaking isn’t even that bad, because De Palma can’t help himself, achieving a great fake mirror shot as a flourish.

Sorry, fellow nerds, but it’s for this reason his best films are the ones he didn’t write. They’re generally the ones written by some of the most famous screenwriters in Hollywood, such as Oliver Stone (Scarface), David Mamet (The Untouchables), and Robert Towne (Mission: Impossible). And sure, none of those films have multidimensional female characters, but at least Michelle Pfieffer, Patricia Clarkson, and Emmanuelle Béart aren’t forced to get their tits out. Obviously, there’s Carrie (1976) and Carlito’s Way (1993) too, and he didn’t write them either. And because De Palma wrote Blow Out, there are no memorable lines, so instead we get memorable shots; no memorable scenes, but plenty of memorable sequences. That’s not to denigrate his filmmaking, it’s just a fact. This isn’t a “good” script. Travolta’s character is haunted by his time helping the police wire undercover cops because of a time a man sweated so much that it shorted the battery, irritating the guy, who had to go to the toilet to remove the wire, was caught, and executed. Does this backstory enhance his character? No. In a Coen brothers’ or Taratino film this sequence would be blackly comic, in De Palma’s hands it’s self-serious to the point of parody.

It has to be said, and I’ll take some flak for this, I’m sure, but for a film all about a sound engineer, it’s not pleasant to listen to. The soundtrack is too obsessed with the grating pops, clicks, crackles, scratches, whistles, slaps, and bangs that sound engineers have to listen to. As a portrait of a man obsessed with sound, both it’s capture and manipulation, and the beguiling effect it can achieve, this is no Berberian Sound Studio (2012).

Someone once said of De Palma that every couple of years he “remakes another Hitchcock film and gives his wife some work”, which is unfair, because this time he’s remaking a Michelangelo Antonioni film. But… with sound not image. If only Francis Ford Coppola hadn’t done exactly that seven years prior and created a seminal entry in the paranoid thriller genre. In fairness to him, De Palma does mention The Conversation (1974) in one of the interviews on this disc, but he justifies Blow Out’s existence because unlike either Blow-Up (1966) or Coppola’s film, it’s specifically about syncing up sound and image, just as Travolta does in one scene, to which interviewer Noah Baubach doesn’t offer the only sane response: [Thor voice] “Is it though?”

Blow Out isn’t a bad film, but it’s not a great one either. It’s an incredibly well-made movie built on absolutely no substance. It’s ridiculous, stupid, and takes itself too seriously. Travolta’s battery-mishap backstory is laugh-out-loud funny, as is the moment when he crashes his car. You wouldn’t have to change a single line, just swap out Travolta for Leslie Nielsen and those sequences would sit happily in a Naked Gun movie. It’s also incredibly misogynistic, and not just by “today’s standards.” For all their titillation, De Palma’s erotic thrillers are as conservative as their contemporaries in the way they punish sexually liberated women. But as I said earlier, you don’t watch Blow Out for the story. You watch it for Vilmos Zsigmond’s cinematography, for De Palma’s use of the camera, and this Criterion release is just as beautiful as they all are. The film looks fantastic, it’s just what it’s looking at that’s the problem.

USA | 1981 | 108 MINUTES | 2.40:1 | COLOUR | ENGLISH

writer & director: Brian De Palma.

starring: John Travolta, Nancy Allen, John Lithgow & Dennis Franz.