‘The Psycho Collection’ (1960-1990)

Arrow Video's 4K Ultra HD Blu-ray box-set brings together Alfred Hitchcock’s original Psycho and its three sequels...

Arrow Video's 4K Ultra HD Blu-ray box-set brings together Alfred Hitchcock’s original Psycho and its three sequels...

Almost a quarter of a century passed between Alfred Hitchcock’s Psycho (1960) and the first of the three sequels it spawned; an exceptionally long gap only occasionally outdone by films like Coming 2 America (2021, 33 years later) and Top Gun: Maverick (2022, 36 years later). Hitchcock’s own The Birds (1963) also didn’t receive a TV Movie follow-up until 31 years later, with The Birds II: Land’s End (1994).

It would be nice to think this derived from an unwillingness to add anything to the near-perfect original, but what’s more likely is that Psycho leaves nowhere obvious for a sequel to go. Its central character Norman Bates (Anthony Perkins) is presumably facing lifelong confinement in a secure psychiatric institution, the secret of his mother has been revealed, and all the other characters are either dead or not particularly interesting.

However, the author of the original Psycho novel, Robert Bloch, released a follow-up story in 1982 (based on a rejected sequel screenplay) and its publication seemed to encourage Universal Pictures to develop a franchise. None of the three films that followed were based on Bloch’s two novel sequels (1982’s Psycho II, and 1990’s Psycho House), instead hewing exceptionally close to the Hitchcock movie. This just isn’t a franchise branching out in new and unexpected directions. “The past is never really past,” says Norman in Psycho III, and the makers of the Psycho series do their best to ensure that.

Naturally, the character of Norman—a little odder now older, and also more definitively heterosexual—is at the core of all three sequels. A Psycho story without him wouldn’t be Psycho. Few other characters reappear, although 1960’s Lila Crane (now called Lila Loomis, again played by Vera Miles) has a central role in Psycho II, and the psychiatrist Dr Richmond from the end of the original film is important in Psycho IV (now played by Warren Frost rather than Simon Oakland).

But in other respects, the three sequels sit thoroughly in the shadow of Hitchcock. They confine themselves, largely, to the Bates house and motel; there are repeated motifs (eyes, birds, the swamp, innocent-seeming milk) and even similar shots (Norman with his hand over his mouth, a woman driving through a storm to the Bates Motel, stuffed birds, Norman’s demented grin). The character Maureen’s suitcase in Psycho III is monogrammed ‘MC’, surely a reference to Marion Crane whom Norman murdered in the original, and there are many other tiny allusions.

The stairs on which Arbogast (Martin Balsam) is killed in the first movie, in particular, are used or referred to over and over again. If anything they’re more emphasised than bathrooms and showers, even though the stabbing of Janet Leigh’s Marion in the shower is by far the original’s most famous scene. Perhaps, in seemingly rare moments of lucidity, the later filmmakers realised that really couldn’t be topped.

Thematically, too, there are close resemblances. The idea that Norman is trapped—geographically by the house and motel, emotionally by his mother, and mentally by his illness—comes through strongly (and the mere existence of sequels tends to reinforce this, just as Gus Van Sant’s 1998 shot-for-shot remake did, by putting Norman into the same situations over and over again).

Sexuality, and Norman’s uncomfortable relationship with it, comes up in all three sequels too; not only in the murder of a boy making out with his girlfriend in Psycho II (confirming its slasher credentials) but in the way all three revolve around Norman’s relationships with women. And not just his mother, though she (and other mothers) are significant too: in Psycho II he has a romance with Lila’s daughter Mary (Meg Tilly), in III it’s the turn of the disillusioned nun Maureen (Diana Scarwid), and by IV Norman is rather implausibly married to Connie (Donna Mitchell), though the idea of Mr and Mrs Bates’s domestic bliss is so inherently dissonant with everything else in the series that the film avoids dwelling on it.

This is also, however, a way in which the follow-ups all differ from the first Psycho. Characters beyond Norman are more developed than Hitchcock’s rather cardboard people—who, Marion apart, are just cogs in the narrative machine—and Norman engages with them more complexly. He exhibits a life beyond his mother.

Whether Perkins lives up to his disarmingly likeable 1960 performance is open to question. He plays the older Norman as a more awkward individual, sometimes taking the nervous tics to extremes (although Perkins’s facial palsy may have been a factor), and with his faintly Scooby-Doo air it’s difficult to know quite how serious he is about the whole thing. His directing of Psycho III suggests his tongue wasn’t far from his cheek at all times.

In any case, even after three further films, Norman is no easier to understand. The 1960 Psycho famously had an “explanation scene” tacked onto the end for the benefit of viewers who needed things spelt out; Psycho II has a similar info-dump near its conclusion, this time from another maternal figure, but while it purports to give us some more precise insight into Norman’s early life it doesn’t explain why he became what he was, or is. Psycho IV in some ways goes further than any of the others in trying to get inside Norman’s head—and this time the “explanation scene” is at the beginning, with Dr Richmond returning from the first film—but many key issues remain unexplored.

Crucial among them is the question of what Norman understands about himself, and his mother. Does he always believe she’s still alive, or only sometimes? If the latter, is he aware at other times that he’s been interacting with an illusion? Does he know (and surely he isn’t a spoiler) that he dresses up as his mother? What’s going through his head when he’s in ‘mother mode’ and who exactly does he believe himself to be? And so on.

Of course, this kind of analytical dissection of Norman’s state of mind was never the point of the original Psycho. And it needn’t have been the point of the sequels either. But they attempt earnestly to elucidate more detail about Norman without doing it satisfactorily. Hitchcock presented him without much comment (except in that closing scene), but the sequels are preoccupied with passing comment and little of it convinces.

Indeed, what stands out most of all about the sequels is how Hitchcock—working with essentially the same material as them—did it so much better. None of them rises much above the dismal, and though there are occasional effective moments, even when they’re not downright bad they tend to be rather tedious. If it weren’t for their connection to the 1960 movie—if they were a standalone slasher trilogy, say—they would probably be completely forgotten.

As it is, however, they do inevitably hold some interest for Psycho aficionadoes, even if it’s sometimes the interest of a train-wreck kind. And they also make Van Sant’s 1998 remake (which almost nobody, except me, seems to like) look like a masterpiece by comparison.

Norman Bates’s mother isn’t happy when her son seems to be growing close to a young woman…

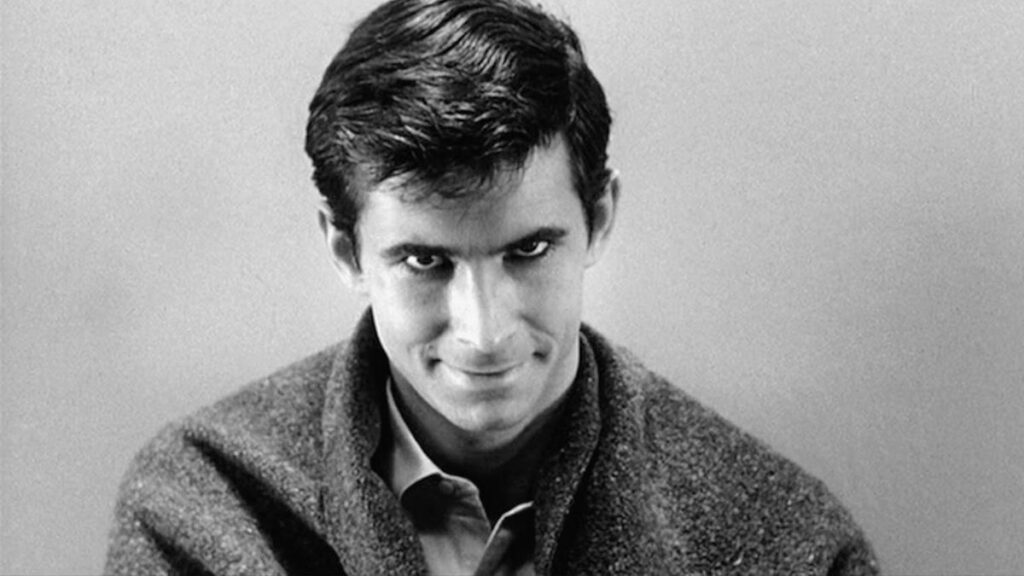

Few movies need as little introduction as Alfred Hitchcock’s Psycho, which gave us—among other things—one of the most famous scenes in all cinema, one of the finest musical scores, and one of the most memorable characters (whose memorability is relentlessly exploited by, but never added to by, the three sequels).

For a recent survey, I rated it the 15th-greatest English-language film of all time, just behind The Searchers (1956) and ahead of The Treasure of the Sierra Madre (1948). A few years ago, too, I reviewed it for Frame Rated on its 60th birthday, characterising it as a bleak, nihilistic, despairing, and extraordinarily economical film, and giving it the highest possible rating.

All the points in that review of course also apply to the same film now featured in this Arrow Video Blu-ray collection. Few of them, however, apply to its three sequels…

USA | 1960 | 109 MINUTES | 1.66:1 (EUROPE) • 1.85:1 (USA) | BLACK & WHITE | ENGLISH

Once again, Norman Bates’s mother isn’t happy when her son seems to be growing close to a young woman…

All three movies repeatedly acknowledge Hitchcock, but Psycho II even more so than the others, opening with lengthy excerpts from the 1960 classic (the neon motel sign, Janet Leigh in the shower, the shocking attack on her to Bernard Herrmann’s string accompaniment) in a manner reminiscent of a TV episode’s recap. Whether this is just to pay homage to Hitchcock is unclear, but in due course, the camera turns to the Bates house and the image turns from black-and-white into colour.

It’s been 22 years since the events of the first movie, and Norman Bates is being released back into society by a court satisfied with his sanity. He returns to the Bates property and is soon falling out with Toomey (Dennis Franz), who’s been running the motel in his absence. (Just one in a series of implausibilities, as the Bates Motel was a commercial non-starter in 1960 and it seems unlikely it would be worth keeping open and unchanged two decades later. Turning it into a ghoulish Serial Killer Experience would have been the best strategy. But that’s an aside…)

More worryingly, Norman also discovers what seems to be an old note from his mother, hears her voice, sees a reflection of a little boy (the young Norman) in a door, and notices the dying hand of Marion Crane in the shower.

Making his favourite milk and sandwiches, he finds a knife in the drawer, and stutters unconvincingly at the word “cutlery”; when he obtains a job at the local diner, another note from his mother appears on the order wheel. “I’m becoming… confused again,” he will confess in due course.

On the positive side, however, Norman also becomes quick friends with Mary (Meg Tilly), a waitress at the same diner. But this doesn’t stop him from sinking deeper and deeper into what seem to be delusions of his mother still being around, and it emerges that Mary and her mother Lila (Vera Miles) have something to do with this…

The number of characters who, at different points, dress up as or declare themselves to be Norman’s mother gives proceedings a slightly farcical air (you’re tempted to yell “Oh no you aren’t!” at the screen), and the big revelation about the role of Lila is predictable, even if disclosures about Mary are more of a surprise.

Loose ends and unconvincing moments abound: why isn’t Mary suspicious when she finds a peephole in the wall? Why would she think Norman is adopted? Why do the local cops talk about murder as if it were a matter of no importance? And an attack in the fruit cellar is both clumsily filmed and extraordinarily lacking in tension.

Visually, Psycho II of course gives the impression of being very colourful in contrast to the mostly sepulchral Hitchcock, though taken in comparison with other movies of its period it’s relatively subdued. There are some effective echoes of John L. Russell’s lighting for the 1960 movie, but altogether the cinematography has a rather humdrum, made-for-TV feel (though it wasn’t), and the same could be said of Jerry Goldsmith’s music score.

Miles and Perkins repeat their roles from the original, but the standout in the cast is Meg Tilly’s Mary. “I’m not living for dead people anymore,” she says, and she is one of few in the entire series of sequels who brings a genuine breath of life into it. Robert Loggia, here playing a doctor, had been considered for the role of Sam Loomis (eventually taken by John Gavin) in the original.

Psycho II has often been considered a surprisingly good sequel, but that’s all it is: a movie not quite as terrible as one might expect. If it didn’t draw so much power from the accumulated myth of Hitchcock’s Psycho, it’s difficult to believe anyone would rate it highly.

USA | 1983 | 113 MINUTES | 1.85:1 | COLOUR | ENGLISH

As you might expect, Norman Bates’s mother isn’t happy when her son seems to be growing close to a young woman…

Perkins stepped behind the camera to make his directorial debut for the third instalment—while still also starring in a role that couldn’t credibly be taken by anyone else—and the OTT, sometimes outright jokey tenor of Psycho III lends credence to the idea that, post-1960, he never took the part of Norman Bates entirely seriously.

Again, like its immediate predecessor, this recycles parts of the original shower scene (and we also get black-and-white “memories” from the end of Psycho II, which is a neat way to tie them in). But the impact of its opening comes instead from the wildly excessive sequence with the nun Maureen (Diana Scarwid) declaring “There is no God!”, followed in short order by a suicide attempt and the death of another nun before Maureen walks off into the desert with a suitcase.

Soon she’s picked up by Duane (Jeff Fahey), a man more interested in a young woman alone than in theological debate. She escapes from him and stumbles across a decrepit Bates Motel, complete with tumbleweed. Norman is busy poisoning birds; in a normal film one might be relieved to know this is merely for taxidermy (which we see him engaging in again in the fourth movie), but given the context of the Psycho story it does hint he may not have made a full recovery.

“You’re my first customer of the day,” he tells her, partially quoting a line spoken by a car salesman in Hitchcock’s masterpiece. (It’s hardly a famous one, and it’s not a particularly important part of the original movie, so this seems more for the filmmakers’ amusement than anything else. Later in Psycho III, Norman’s “we all go a little mad sometimes” line also gets repeated.)

Through a coincidence that’s a bit too good to be true, Duane also shows up again and becomes assistant manager of the motel, all while journalist Tracy (Roberta Maxwell) investigates Norman and his story.

Psycho III is not out-and-out comedic but it does come close at times, and much of the humour works fairly well: from a clever though slightly ridiculous twist with a character attempting suicide in a bathtub, to an outrageous gag with an ice chest (the groundwork well-laid), to some witty lines (Maureen apologising for leaving the bathroom in a mess, Norman responding “I’ve seen it worse.”)

At times, though, the fun that Perkins and writer Charles Edward Pogue are having with the franchise is taken a bit far: a visit to the motel by a group of football fans becomes distinctly Carry On Psycho. There are dramatic fails too, including an unnecessarily complicated series of twists about the real identity of Norman’s mother, and Perkins’s direction is little more than competent: a murder in a phone booth comes across as completely unreal, for example.

Among the cast, Scarwid spends too much time sitting around crying, but Fahey has some charisma (imagine an obnoxious version of Brad Pitt in 1991’s Thelma & Louise). Peculiarly, Perkins is visibly older than he looked in Psycho II though the movies are set only a month apart, and only a few years separate their production. It’s not clear why, or whether this reflected changes in his off-screen appearance.

Psycho III has few aspirations of being serious and, as a result, many fans of the 1960 movie will find it more pleasing than Psycho II, which can seem to strive too hard to achieve gravitas. That’s certainly not the case here. Still, it’s not always easy to be sure when it’s trying to be funny, and when it’s just so bad it’s funny.

USA | 1986 | 93 MINUTES | 1.85:1 | COLOUR | ENGLISH

Just for a change, Norman Bates isn’t happy when his mother seems to be growing close to a man…

For the final Psycho movie Joseph Stefano, the screenwriter of Hitchcock’s original, returned—and although it was the only one made for TV, the result is a movie with a more complex narrative than either of the preceding sequels, linking a storyline about a now middle-aged Norman (released again from an institution) with an often intriguing portrayal of his childhood. This is surprisingly effective at a structural level, though the execution of individual scenes and characters is less satisfying.

Psycho IV: The Beginning is thus the only one of the movies to venture into the prequel territory later explored by the TV series Bates Motel (2013-17). (Incidentally, it only occurred to me writing these reviews—after nearly four decades of getting to know Hitchcock’s Psycho over countless viewings—how strange the name of the motel is. Very few, in my experience, employ the surname of the owners… but then, Golden Sunset Lodge might not have conjured up quite the same atmosphere.)

Psycho IV opens with, and will repeatedly return to, a radio talk show hosted by Fran (C.C.H Pounder), with Dr Richmond (Warren Frost)—who examined Norman Bates at the end of the Hitchcock movie—as her guest to discuss the subject of matricide. Linette (Kurt Paul), who has killed his mother, is an early interviewee but inevitably Norman soon calls in, using the name Ed.

This is likely an oblique reference to the Wisconsin serial killer Ed Gein, on whom Robert Bloch had loosely based his novel, but the question of whether—or when—Fran and Dr Richmond will realise who they are talking to provides one long-running strand of suspense in Psycho IV.

A bigger one is provided by the back-story of the young Norman, shown through Henry Thomas (E.T. the Extra-Terrestrial) playing the boy and Olivia Hussey the living (and surprisingly young) mother, and also recounted by the older Norman in conversation with Fran. His mother had been unpredictable, he says, and this made him insecure. The insecurity is exacerbated when she takes on a new lover, Chet (Thomas Schuster), and it’s also evident to audiences—though not stated explicitly by Norman or the movie—that his mother has repressed incestuous longings for him (and not vice-versa).

Stefano and director Mick Garris (Critters 2) put all this across in a largely straightforward but effective way, just occasionally giving into the temptation of reflecting Norman’s mental chaos on-screen. At his father’s funeral, for example, his mother speaks in Norman’s voice, and the adult Norman also appears. The message, of course, is that the mother, the adult man and the boy are now barely separable.

Psycho IV differs from the others in moving Norman out of the Bates house into a different, more modern and frankly rather nice residence, presumably paid for by his psychiatrist wife Connie (Donna Mitchell). We don’t see much of her, however, raising suspicions that she exists only to regret her marriage; and the action soon enough moves to the familiar Gothic pile of the first three films, anyway.

Visually Psycho IV often looks better than its two predecessors, even if there’s still an aura of cheapness hanging over it; there are some well-imagined shots and a well-editing, tantalising title sequence. Still, if it’s generally less obviously clunky than the other two, it has its share of clunks.

There’s a definite sense of actors reading lines, and while Pounder and young Thomas handle their roles convincingly, Hussey and Schuster let the film down with exaggerated and shallow performances. The latter has some particularly cringeworthy lines. In fairness, it should be noted that we are (presumably) seeing them in Norman’s recollection, which might not be true-to-life, but it may also seem unlikely the film is trying to make a subtle point about the unreliability of memory.

Graeme Revell’s music score doesn’t actively detract from the movie the way those performances do, but it’s certainly not interesting either (unlike the excerpts from Bernard Herrmann’s 1960 score that’s also used)—and that’s the problem with Psycho IV as a whole. It’s rather slow, there’s little in the way of extended and meaningful dialogue between characters, its attempts to get to grips with issues like mental illness and abortion are half-hearted, the conflict between Fran and Dr Richmond is rather dull and pointless, and one character’s actions at the end make little sense.

And, of course, the eventual direction of the backstory sections is preordained (regardless of whether Psycho IV exists in the same world as II and III or presents an alternative continuation of the 1960 film, as sometimes suggested).

We all know what’s going to happen to Norman, his mother, and her boyfriend. The only real question at this stage is what’s going to happen to Norman’s brave—or foolhardy—new wife, and it’s legitimate to wonder whether, after more than five hours of so-so Psycho sequels, any of us care.

USA | 1990 | 96 MINUTES | 1.33:1 (TV) • 1.85:1 (THEATRICAL) | COLOUR | ENGLISH

Hitchcock’s original Psycho has been the subject of numerous books, countless articles, and many deep critical analyses. The other three, understandably, have not. Still, Arrow Video’s tried valiantly to make up in quantity for what’s inevitably lacking in serious critical treatment, and the assembly of special features on the Psycho II disc is especially good.

Relatively little of the special feature material is new, and that on the first disc is a straight lift from a previous reissue of the film. Most potential purchasers of this set will, of course, be Psycho completists buying it primarily for the sequels, so that may not matter much.

Given that photography is not a particularly strong point of any of the sequels, sensational visual quality should not be expected of these new 4K versions, but the transfers are unproblematic.

directors: ‘Psycho’: Alfred Hitchcock. ‘Psycho II’: Richard Franklin. ‘Psycho III’: Anthony Perkins. ‘Psycho IV: The Beginning’: Mick Garris.

writers: ‘Psycho’: Joseph Stefano (based on the novel by Robert Bloch). ‘Psycho II’: Tom Holland. ‘Psycho III’: Charles Edward Pogue. ‘Psycho IV: The Beginning’: Joseph Stefano.

starring: ‘Psycho’: Anthony Perkins, Vera Miles, Janet Leigh & Martin Balsam. ‘Psycho II’: Anthony Perkins, Vera Miles, Meg Tilly & Robert Loggia. ‘Psycho III’: Anthony Perkins, Diana Scarwid, Jeff Fahey & Roberta Maxwell. ‘Psycho IV: The Beginning’: Anthony Perkins, Henry Thomas, Olivia Hussey & C.C.H. Pounder.