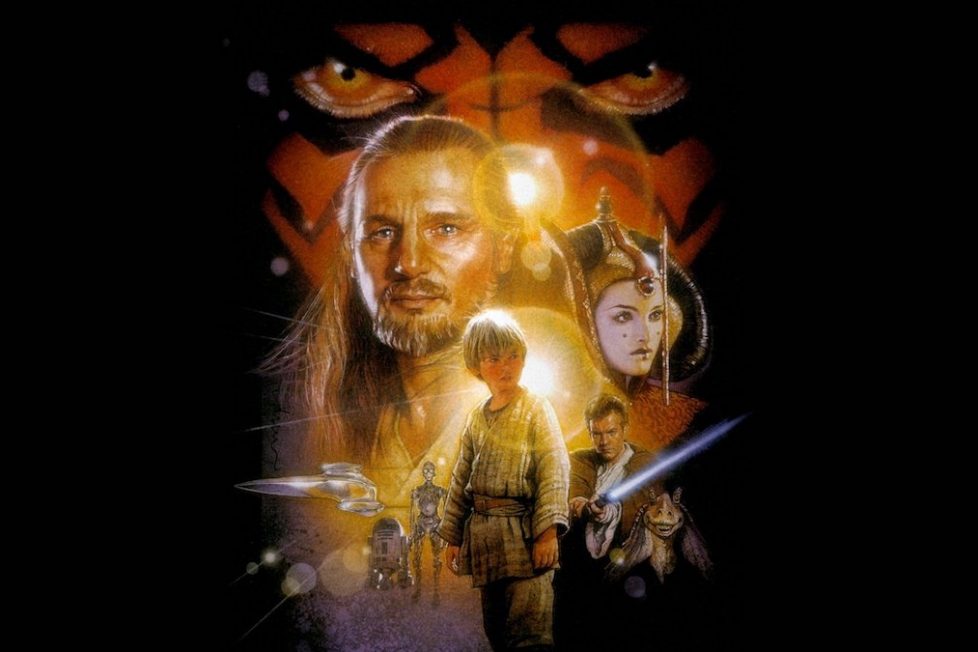

STAR WARS: EPISODE I – THE PHANTOM MENACE (1999)

A short time ago, in a cinema not far away...

A short time ago, in a cinema not far away...

One of the clearest memories I have of the first time I watched Star Wars: Episode I — The Phantom Menace (hereafter Phantom Menace) is of my brother, who’d already seen it, taking me to the cinema as a late birthday present. He didn’t mind a rewatch: as a twenty-something in 1999, he had endured the whole, excruciating 16-year hiatus in the Star Wars production since Return of the Jedi (1983).

Rumours about the continuation of George Lucas’s space opera had been circling for years, until the prequels were finally announced in 1997 after the divisive ‘Special Edition’ re-releases of his original trilogy. The hype was at galactic levels by 1999, and fans were ready to queue for days to score tickets to the very first screening in Los Angeles.

I’m more than 10 years younger than my brother, so my approach was completely different. I had obviously watched the original trilogy, but only a handful of years before. Although I felt the need for more Star Wars, I couldn’t possibly appreciate the hysteria surrounding this millennial cinematic event.

I have few memories of those early days, but I actually remember very well my older brother sitting next to me at the cinema, asleep no more than 15 minutes into the film. This image still perfectly conveys the utter disappointment Phantom Menace represented. Granted, after so many years of hype and anticipation, even the second coming of Christ would fall short of fan expectations, but it’s undeniable that Phantom Menace, and by extension Lucas himself, got way too many things wrong, and will be forever remembered as an embarrassment to the franchise.

If there is ever a time to take stock of our lives, what we are and what we can learn, turning 18 is one of the most important milestones. Phantom Menace’s coming-of-age seems a fitting occasion to take a look back at its legacy…

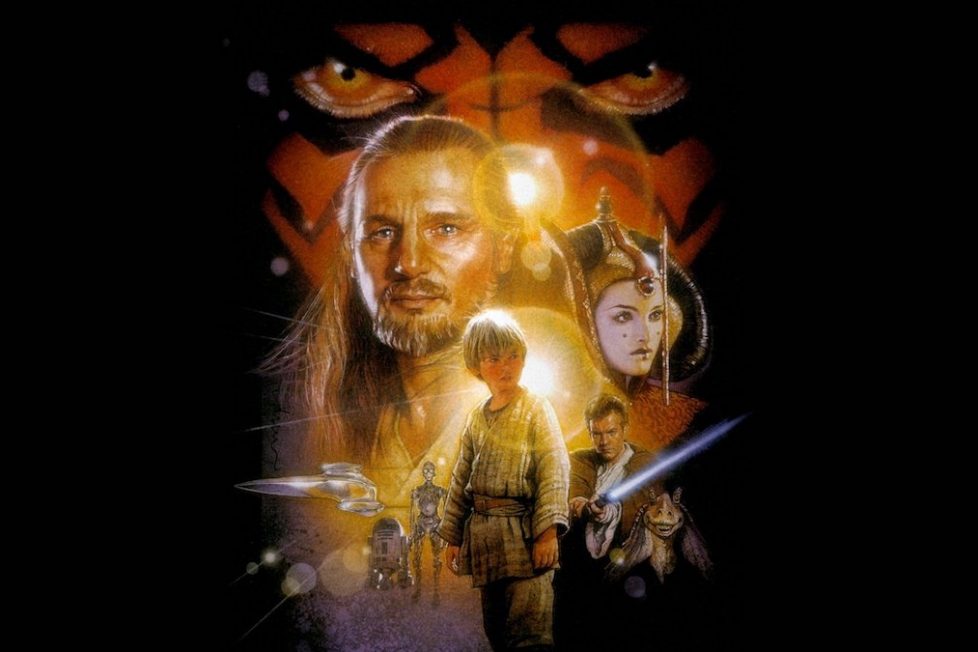

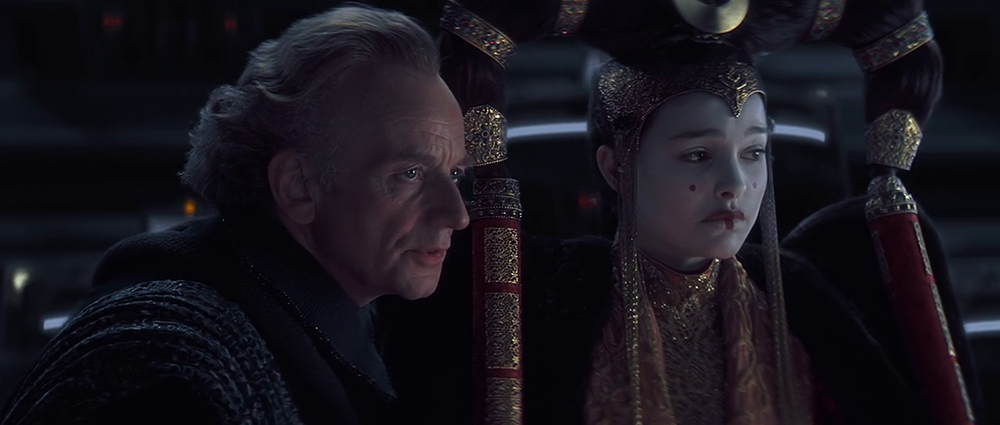

An incalculable number of words (at least 12 parsecs) has been spent to dissect the intricacies of Phantom Menace’s plot, which twists around the Queen of Naboo’s mission to thwart an attack on her planet, with a backdrop of trade disputes, manipulations, and conspiracies in the galactic Senate. After many rewatches and multiple reads of Star Wars material, I still have millions of questions about character motivations and storytelling logic, especially what duplicitous senator Palpatine’s trying to achieve and how.

The original Star Wars (1977), rebranded as as Episode IV — A New Hope in 1997, was about a teenager, an old monk, and a space cowboy, trying to save a princess kidnapped by a dark knight. It was an adventure children and adults alike could instantly relate to. Which kid could ever like the stern, cold Qui-Gon, or the whiny Obi-Wan of Phantom Menace? Or the irritating slave boy who doesn’t show up until one hour into the film, for that matter? Who wants to hear more about the taxation of trade routes?

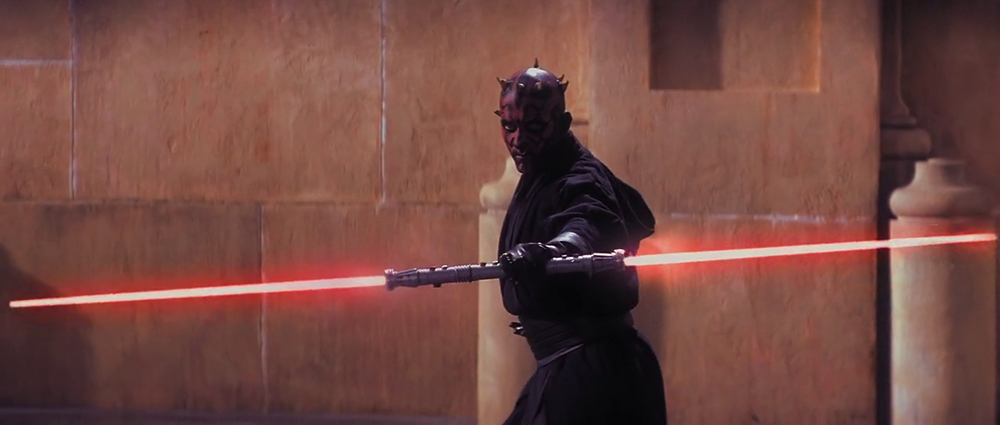

Critics didn’t particularly like Phantom Menace, but they unanimously praised its visual effects. Lucas himself waited so long to resuscitate the saga because he was waiting for technology to evolve enough to match his imagination. The result: only one scene in Phantom Menace was filmed without an element of greenscreen. The director had no constraints in creating vivid worlds, unique characters, and grand action scenes. He asked for characters’ costumes to look elaborate and sophisticated. He exploited new editing techniques to tweak and digitally correct actors’ performances. The film consequently looked stunning, at least at a first glance. But in doing all this, Lucas forgot to portray even a glimpse of the misery forced on the victims of the invasion in Naboo; he forgot to give the slightest trace of personality to Darth Maul, one of his most badass-looking villains; he forgot to add the bare minimum of dramatic stakes in most of the overdone battle sequences.

Star Wars was the third film George Lucas ever directed, and 22 years later Phantom Menace became the fourth. Although he’d been writing, producing, and executive producing, by 1999 he hadn’t sat in the director’s chair for over two decades. For the original trilogy he also had help from screenwriter Lawrence Kasdan, mentor Irvin Kershner, director Richard Marquand, his then-wife Marcia, and many others who helped shaped Star Wars as we know it. For the prequels, Lucas ran wild with his ideas, unhindered and enabled by a team of producers and corporate yes-men. He ended up with a soap opera filled with dull, sketchy, borderline racist characters, awful dialogue, and a vapid, incoherent story. Plus, the infamous Jar Jar Binks.

In hindsight, post-Star Wars: The Force Awakens and Rogue One: A Star Wars Story, we can at least commend Lucas’s attempt at giving life to a new idea without sticking too much to the original trilogy’s blueprints. The Death Star (or its equivalent) is the perfect example of this. Although JJ Abrams and Gareth Edwards’s films turned out to be far better than Phantom Menace, they still followed the same path Lucas created 40 years ago. A path that, it’s worth remembering, Lucas created after taking inspiration from early American sci-fi and the work of Akira Kurosawa. This is probably why Rogue One’s war scenes are the most powerful in the film: because they hint very clearly to a completely different source of inspiration.

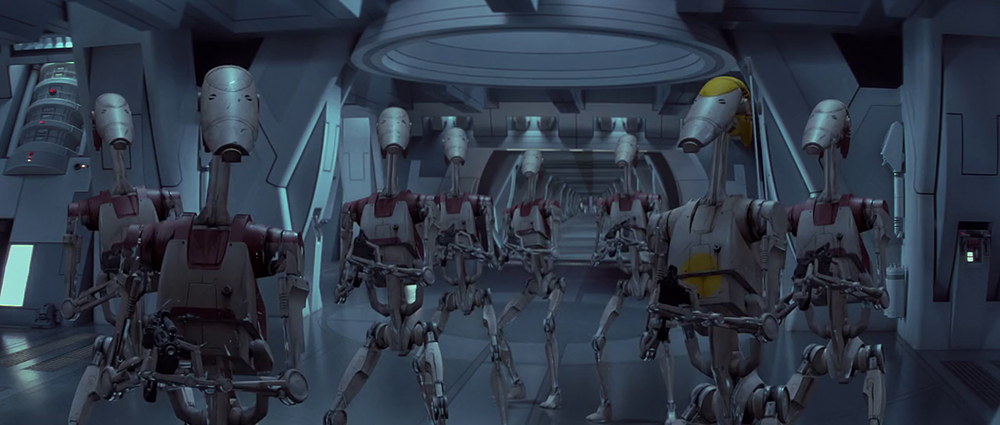

An unintended consequence of Phantom Menace’s abundance of lightsaber duels and use of the Force, which many welcomed, was that supposedly threatening situations became completely bland. Think of Luke and Han rescuing Princess Leia in the Death Star (fighting with laser guns and retreating in the garbage compactor), then compare this with Qui-Gon and Obi-Wan effortlessly mowing down droids in the Trade Federation spaceship. What are the consequences for the characters?

In Phantom Menace we never get to see them interact as effectively as in A New Hope (Leia: “You cut off our only escape!”, Han: “Maybe you’d like it back in your cell, Your Highness!”). The polished, lavish sets might be designed to perfection and rich in detail, but they’re instantly forgettable compared to the shoddy, rusty spaceships, or the dark Mos Eisley cantina. The sandstorm in Tatooine never gets as real as Luke tinkering with tools, rags, and motor oil to clean the droids. Phantom Menace taught us that we can’t fully appreciate the extraordinariness of space travel, the mysticism of the Force, and the flashy lightsaber duels without the little earthly moments the original Star Wars was made of.

Jake Lloyd’s performance as young Anakin was distracting and irritating — one of Phantom Menace’s biggest flaws. The venomous attacks against him, just nine years old at the time of filming, directly led him to quit acting. In a similar way, Hayden Christensen still bears the brunt of all jokes for playing an older Anakin Skywalker in Attack of the Clones and Revenge of the Sith. Time gave us the chance to reflect, and reach a more mature conclusion: they might have been guilty of poor performances, but what about the person who was supposed to direct them, or write their lines?

Phantom Menace proved that all the nitpicking on the plot and snarky jabs at the characters cannot downplay Lucas’ enormous responsibilities. It also showed us that resentment is a nasty feeling: when Daisy Ridley and John Boyega became the new victims of misplaced Star Wars purism, if not plain discrimination, critics and real fans closed ranks and energetically defended them.

Enough with overblown computer-generated elements, and enough with actors constantly swallowed in greenscreen, endlessly talking while sitting down. No more absurd plot points just to squeeze in an action sequence. No more Asian-sounding accents for funny or evil characters. Phantom Menace made us less sycophantic in our quasi-fetishist veneration for Star Wars: we are now aware it’s just a movie. It’s nothing sacred. Actors have passed, filming has changed, cinema is now different. All we hold dear from Star Wars, Empire, and Jedi can’t be replicated. It’s up to a new generation of filmmakers to take those stories from a galaxy far, far away, and give them a new lease of life. And we shall be there, queuing in the cinema, waiting to be amazed once again.

Star Wars: Episode I — The Phantom Menace premiered in Los Angeles on 16 May 1999. Happy birthday, dear friend. You were a surprise, to be sure… but a welcome one.