SPACESHIP EARTH (2020)

A look at the group of people who built the Biosphere 2, a giant replica of the earth's ecosystem, in 1991.

A look at the group of people who built the Biosphere 2, a giant replica of the earth's ecosystem, in 1991.

Spaceship Earth is an unassuming telling of an extraordinary story. Or, rather, two stories: the ‘Biosphere 2’ experiments of the early-1990s (in which people were sealed inside an artificial habitat for years), and the tale of the group that conceived of the idea.

In fact, it’s not really about the ‘Biosphere 2’ project much at all. Those seeking engineering minutiae or detail on everyday life inside this giant structure in the Arizona desert will come away disappointed. It’s more about the people—but, again, not so much the so-called ‘Biospherians’ who participated in the experiment, but the folk behind it, who all came together in 1960s counterculture and never split up.

Filmmaker Matt Wolf achieves his aims through a mix of archive footage, talking-head interviews, and still images. He’s fortunate that the group were keen on documenting their activities on camera from the start, and that Biosphere 2 was a big enough news story in the ’90s to generate plenty of TV coverage. Throughout Spaceship Earth, Wolf presents events in an uncomplicated manner, minus any fancy titles or editing tricks. And the music complements the general mood nicely, too, while being slightly obtrusive at times.

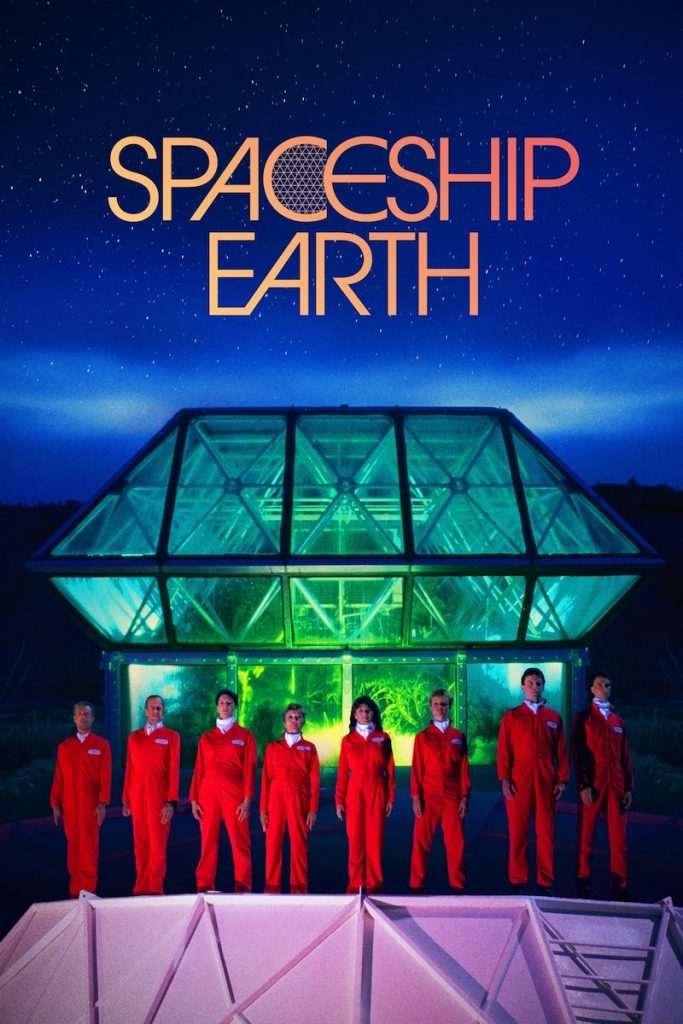

Although the film begins in 1991 with the initial eight volunteers entering Biosphere 2 for a two-year stay, each clad in camp Star Trek-style red jumpsuits, it almost immediately switches focus to the project’s progenitors after a TV commentator observes “its supporters say it’s science, its detractors say it’s a tourist attraction run by questionable characters”.

Those characters will be the actual focus of this documentary film, and indeed we’re immediately swept back to San Francisco, 1966, where a bunch of not-quite-hippies became aware of contemporary ideas about impending ecological catastrophe thanks to writers like Rachel Carson.

Their ringleader is John Allen; a former meatpacker, metallurgist, union organiser, army engineer, and Harvard student. Under his charismatic direction, the team build themselves a homestead (Synergia Ranch, near Santa Fe in New Mexico) which about 20 of them live together inside, trying their hand at a sustainable lifestyle.

Already one can see the beginnings of what led them to Biosphere 2 more than two decades later, but we also start to suspect this is more than a group of like-minded friends. Could they be a cult?

The participants (interviewed in the present-day) laugh any cult associations off, however. And, indeed, there’s not the barest hint of coercion or dubious practices going on. Instead, they embark through the 1970s and 1980s on a series of ventures far grander than one might expect from their origins, like building an oceangoing ship and setting up a hotel in Kathmandu and an art gallery in London. They’re hippie-capitalists, perhaps, and their ambition is huge. “The magic of the entire enterprise was to always increase the challenge”, says one.

By the early-1980s the team is running environmental conferences when plans to create Biosphere 2 start to take shape. (They named it so to imply that “Biosphere 1” was planet Earth, which hadn’t worked out, prompting a need to rethink our relationship with the environment.)

The biosphere (a vast steel-and-glass structure covering more than three acres) would come to contain multiple different ecosystems complete with plants and animals—including a rainforest and a coral reef and grassland, as well as more than a thousand sensors to monitor every facet.

Critics called it entertainment rather than science, arguing there were too many variables to draw firm conclusions from whatever transpired. But although many scientific experts were consulted during its creation, it wasn’t intended as an “experiment” in the formal sense of the word. It was more of an opportunity to learn. Great attention was given to its potential for teaching us about mankind’s long-term survival prospects beyond Earth, though that wasn’t its sole reason for existing.

Of course, this project cost a lot of money, and though the Synergia Ranch group had been successful in their earlier business ventures they still needed to bring in an outside backer. Step forward Ed Bass, a Texan oil billionaire and philanthropist. Amiable as he seems, Bass’s arrival on the scene is the big turning point in Wolf’s documentary. This is where it all starts to turn sour, in terms of how the Biosphere 2 project was conducted and the bitter management wrangling outside its perimeter.

The film is careful not to blame Bass, or anyone else, for the many problems encountered. The impression one gets is both that the founders simply bit off more than they could chew, and that Bass didn’t see eye-to-eye with them on the way everything should be run.

The actual experiment, to which Wolf returns about halfway through the movie after that lengthy narration of the Synergia group’s background, was also fraught with issues. The structure was supposed to be airtight (the inhabitants only had phone contact with the outside), leading to major problems with the carbon dioxide levels. To remedy this, a CO2 scrubber (shades of Apollo 13) was installed in secret. It’s argued in the film that this made little overall difference to the environment inside the biosphere, but the lack of transparency casts doubt on the project’s bona fides, given that the absence of outside help was its much-trumpeted purpose.

Similarly, when one Biospherian was temporarily released to go to the hospital after an accident with a threshing machine, she wasn’t even supposed to eat in the outside world because the purity of self-containment would be sullied. But she smuggled in two bags of supplies…

We see comparatively little of the biosphere’s interior, alas, or at least little that’s informative, apart from some work sequences that evoke some atmosphere. Certainly, Wolf doesn’t seem interested in the dynamics that must have developed among the Biospherians over their glasses of home-made banana wine. Sometimes that’s a pity. For instance, it’s striking that on their last day (termed “re-entry”) some people didn’t want to come out of their two-year lockdown. But there’s little insight into the experience’s effect on its participants, as the real drama of Spaceship Earth takes place outside.

Is this just another story of big bucks elbowing out idealism? Many filmmakers would be tempted to play it that way, but Wolf resists. There are no obvious heroes or villains here, and even the Synergia group (many of whom are still together to this day) don’t seem to harbour any resentment of Bass. After all, they were capitalists in their way, and he was an idealist in his. Perhaps there’s no Big Lesson to be drawn from Spaceship Earth… except that, despite best intentions, things won’t always go to plan.

It’s a remarkable tale, and one to which Wolf’s straightforward style is well-suited. He lets the material tell the story. Spaceship Earth can be confusing sometimes, however. It’s not made clear enough that there were two separate sets of biosphere inhabitants at different times, and it’s not always evident who’s talking on camera, or easy to remember who’s who among the interviewees.

But this isn’t a movie about precise details. What stays with you is the sense of potential glimpsed even in failure, and the way that a ragbag group stuck together for decades to pursue dreams that sounded absurd, to eventually built a whole new world.

USA | 2020 | 113 MINUTES | 1.33:1 • 2.35:1 | COLOUR | ENGLISH

director: Matt Wolf.

starring: John Allen, Tony Burgess, William Dempster, Kathy Dyhr, Kathelin Gray & Marie Harding.