Savage Guns: Four Classic Westerns Vol.3 (1968-1975)

Maniacal outlaws thirsting for blood! Corrupt capitalists profiting from the suffering of the common folk! Desperate people pushed to violent revenge!

Maniacal outlaws thirsting for blood! Corrupt capitalists profiting from the suffering of the common folk! Desperate people pushed to violent revenge!

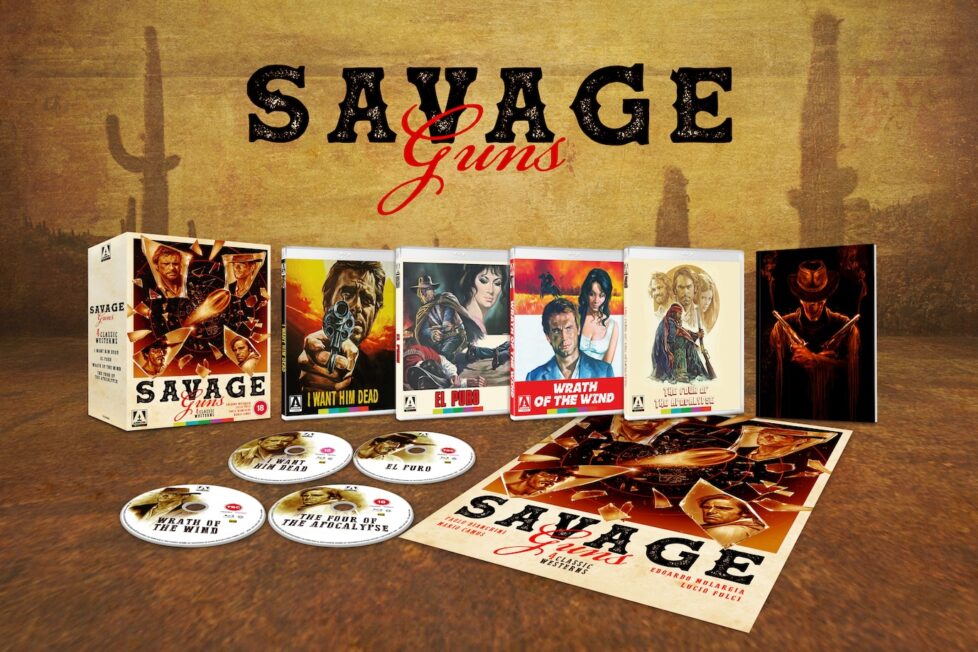

Preceded by Arrow Video’s Vengeance Trails and Blood Money box sets, this latest quartet of European westerns is the third volume of what has, so far, presented an excellent catalogue of the multi-facetted spaghetti western genre. Collected here are a few of the most atypical examples, each restored from 2K scans of the original 35mm camera negatives and handsomely packaged on separate Blu-ray discs with individual artwork and plenty of appropriate bonus material.

That said, Paolo Bianchini’s well-crafted I Want Him Dead (1968) is first up and so predictably by-the-numbers that it’s a reminder of what was, by then, a well-worn template. It provides a useful yardstick against which the other three movies can be compared. Edoardo Mulargia’s El Puro (1969) is a complete change of pace that takes a bunch of tired tropes and deliberately remixes them into a metaphysical character-study carried by western stalwart Robert Woods. Wrath of the Wind (1970) is hardly a western at all with its indeterminate period setting and Terrence Hill cast against type in a provocative political allegory directed by Mario Camus. Finally, the last film standing is Lucio Fulci’s Four of the Apocalypse (1975), starring two fan favourites of Italian pulp cinema, Fabio Testi and Tomas Milian, in a delightfully dark foray into the fringes of the genre that’s certainly the most interesting.

An ex-Confederate soldier vows revenge after his sister is raped and murdered, but finds himself embroiled in a dastardly plot to disrupt peace talks between the North and South.

Who wants who dead? That’s the question, and it’s not long until there’s plenty of candidates for both. The opening minutes of I Want Him Dead / Lo voglio morto are promising, with sweeping shots of vast landscapes and close-up portraits of characters that suggest a tale of enduring landscapes and the transient human endeavours to conquer them. This is indeed part of the story’s essence.

Clayton (Craig Hill) and his sister, Mercedes (Cristina Businari), are hoping to buy a run-down ranch and make a fresh start. The first action scene makes use of some clever camera work as Clayton spots the reflection of a stealthy rifleman in his cup of very black coffee. It’s an ambush, suggesting that the lives they’re fleeing are in danger of catching up with them. Apparently, this brief though rather fine sequence was improvised as an afterthought to meet the desired body count specified by the distributors. Clayton dispatches several attackers with the ease of a seasoned gunslinger and the two settlers pack-up and move on to the nearest town, where he leaves his sister in the safety of the hotel before riding off to seal the deal with Mac (Tomás Blanco) for their new homestead. He’s hoping to pay with US dollars, but is told that due to the war his savings are worthless, and Mac demands the payment in pesos.

In his absence, Mercedes has caught the eye of Jack Blood (José Manuel Martín), a bandit working for local arms dealer, Malleck (Andrea Bosic). This was Cristina Businari’s screen debut after winning Miss Italia 1967 and, as is often the case for a pretty woman in a western, Mercedes is only there to get raped, beaten, and clearly define who the irredeemable bad guys are while providing the motive for our hero’s revenge. On his return, Clayton finds her dead and the only clue to the identity of her attacker is a draw-string coin purse she managed to hold onto.

While still in shock from discovering her body, he lashes out at an obnoxious drunk in the hotel saloon who draws a gun. Of course, Clayton’s faster and the contingency of Confederate soldiers who’re drinking there agree it was self-defence. However, the man was the Sherriff’s brother so, instead of helping find the murderer of Mercedes, the corrupt Sherriff (Remo De Angelis) decides that he wants Clayton dead, who manages to escape summary execution after a severe beating, setting out to track down Jack Blood, whom he wants dead. So, he now pursues his sister’s killer while being pursued by the Sherriff and his cronies.

Thus, everything about this story of tangled vengeances is laid out in the first 15-minutes or so, but there’s still plenty to enjoy in Paolo Bianchini’s I Want Him Dead, despite a terrible script by Carlos Sarabia—probably a random nom-de-plume because the real writer didn’t want to own up. The underlying story has some good points, and it seems the original treatment was penned by the uncredited Adriano Bolzoni, who had a hand in Sergio Leone’s A Fistful of Dollars (1964), and Maurizio Lucidi’s My Name is Pecos (1966). He also contributed to the screenplay for notable giallo, Your Vice is a Locked Room and Only I Have the Key (1972), co-written and directed by Sergio Martino.

Bianchini was a jobbing director with arthouse aspirations who debuted with the espionage thriller, Our Men in Bagdad (1966), followed by two science-fiction films—The Devil’s Man (1967) with its bonkers brain-swapping premise, and the low-budget Massacre Mania (1967) starring Robert Woods, an actor much better known for his roles in westerns, a genre Bianchini then took on with two films made back-to-back God Made Them… I Kill Them / Dio li Crea… Lo li Ammazzo! (1968) and I Want Him Dead.

There are some inspired shots here, including an extended fight scene filmed among horses, their legs framing the action. There’s plenty of extreme wide shots, close-ups, and great use of dynamic angles and depth of field—it all looks exactly how a spaghetti western should. But, although the story suggests several interesting strands and there are one or two surprises, I Want Him Dead never quite surmounts its poor screenplay.

Being a typical western hero—unable to process emotions except through action—Clayton tracks down his sister’s murderer to a band of deserters and bandits who bond through slapping women around while laughing raucously. In some scenes they’re already laughing as we join them but it’s rarely clear what’s tickled them. They can’t seem to stop, even when eating messily with their mouths open and slopping cider down their beards—which seems to be a compulsory scene for most spaghetti western villains. Perhaps it’s meant to lighten the tone a little, but it grates and gets tiresome. Though, it does grant some respite from the unrelentingly hackneyed dialogue which is only ever expositional.

Clayton finds accomplices in Aloma (Lea Massari) and Marisa (Licia Calderón), two women who clean and cook but are also expected to ‘entertain’ the men at one of Mallek’s ranches. Theatre-trained Lea Massari turns in the strongest performance and it’s a pity she isn’t given more screen time and better dialogue, especially in her scenes with Hill. Clearly, Clayton’s attracted to Aloma, and the younger Marisa reminds him of his sister. Perhaps he can atone for his failure to protect Mercedes by saving them instead? He briefly infiltrates the gang and learns of a plot to assassinate two generals who plan to discuss an armistice between the warring Confederates and Unionists, placing the film’s period firmly in 1865—the final year of the American Civil War. For an arms dealer like Mallek, peace would be bad for business. So, he wants them dead, hoping both sides would blame the other and rekindle hostilities. Can our hero pursue personal vengeance as well as preventing political catastrophe?

ITALY | 1968 | 87 MINUTES | 1.85:1 | COLOUR | ITALIAN • ENGLISH

A legendary gunfighter has to fight alcoholism and a gang of ruthless bounty hunters intent on removing the competition.

El Puro / La taglia è tua… l’uomo l’ammazzo io (a.k.a The Reward’s Yours… The Man’s Mine) takes us into refreshingly different territory of both style and story. We all know the drunken sheriff-cum-gunslinger stereotype, but instead of using this as a stock character, we spend a great deal of time with them, getting into their mindset and slowly building empathy for the central antihero. Wanted, dead or alive, Joe Bishop (Robert Woods) is hiding from his bloody past as ‘El Puro’, a notorious gunslinger whose primary employment seems to have been keeping some sort of order south of the border—a kind of mercenary enforcer protecting those who could pay for his services. His clients included Fernando (Gustavo Re), who forewarns him about the gang of desperados intending to fill the position he’s left vacant, after they prove themselves worthy by killing him and collecting the $10,000 bounty. But who can El Puro trust, after all. Fernando could sure use the reward money, too…

Director Edoardo Mulargia is very aware of the familiar tropes being employed, relying on a few genre clichés to quickly establish characters before examining them from more unusual perspectives. For example, Tim (Mario Brega), one of the desperados is introduced with the rape of a random underage girl after he strangles her grandfather for trying to protect her. That the rest of the gang are fine with that clearly defines who the irredeemable bad guys are. Going against the formula, we meet El Puro, too incapacitated to resist as he’s severely beaten for not paying his excessive bar bill. By chance, he’s recognised by one of the saloon girls, Rosie (Rosalba Neri), who also comes from south of the border where he’s infamous but seemingly liked by the poor people for protecting their villages from outlaws, ostensibly so they can continue working for the landowners who pay his fees.

Rosie takes El Puro in and cares for him, suggesting they both make their escape to settle into a normal life together. But we know the genre won’t let him escape his past so easily. Rosalba Neri was already a veteran of pulp cinema with around 70 previous appearances and fresh from working with cult Spanish director Jesús Franco on The Castle of Fu Manchu (1969) and Marquis de Sade’s Justine (1969). I know her from Silvio Amadio’s accomplished giallo, Smile Before Death (1972), also recently released by Arrow Video. Here, she’s as reliable as ever, adding extra depth and strength to a role she elevates above the ‘hooker with a heart of gold’ trope.

The principal cast are all great, perhaps responding to the central performance of Robert Woods as the alcohol-damaged, formerly feared gunman unable to escape his own legend. This character study of a damaged man suffering the post traumatic stress of being a macho western hero propels the narrative, taking in a couple of metaphysical sojourns along the way. In one way, El Puro is no more, and we are witnessing his struggle to be reborn. The allegory of a repeating cycle of death and reincarnation was a deliberate subtext in the initial script that Mulargia retained, though played down.

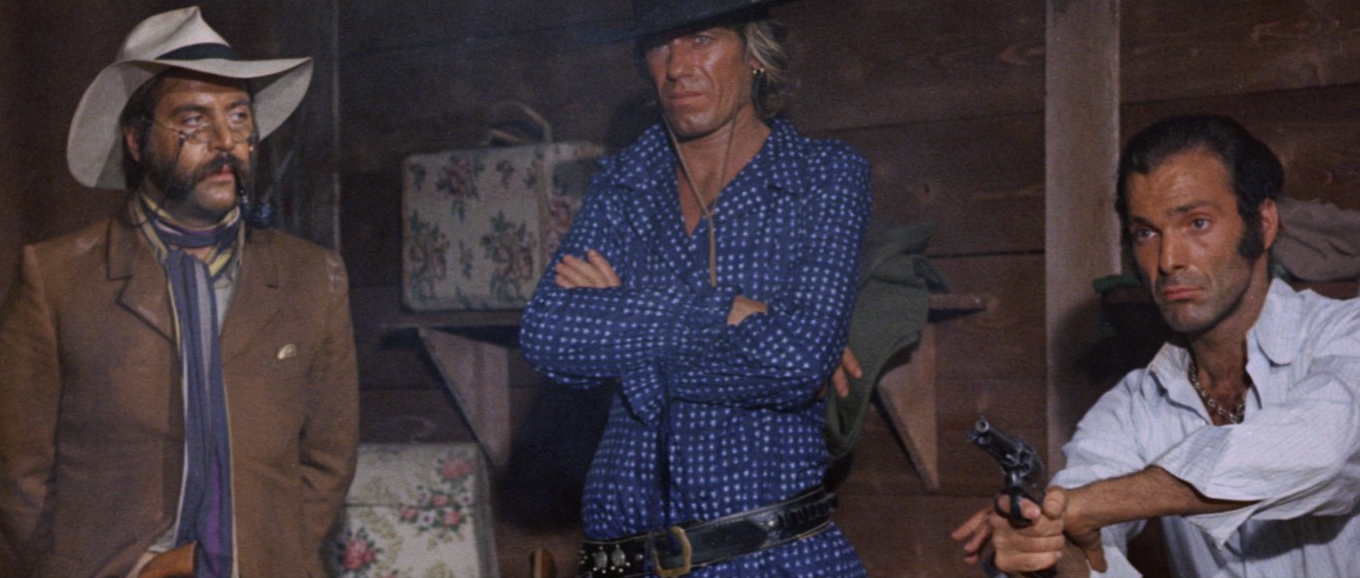

Gypsy (Marc Fiorini) is the psychotic leader of the gang seeking El Puro and is also conducting a metaphysical battle with personal demons. American actor Marc Fiorini put his own spin on the tormented villain trope and apparently relied on copious drugs to bring an off-kilter sense of unpredictable menace to the character. Gypsy suffers hypnopompic hallucinations and shoots at phantoms but also seems morally torn when he shoots a sheriff who is only performing his duty. His number one henchman, Cassidy (Aldo Berti), is also effectively chilling with a contrastingly quiet and understated performance that still speaks eloquently of brooding passions and barely restrained violence. At the culmination of one of the most brutal scenes, in which he beats a woman to death, Gypsy is moved to praise him as “magnificent”, and they exchange an ardent kiss. Far as I know, this is the first cowboy-on-cowboy snog in cinema, beating Brokeback Mountain (2005) to it by three-and-a-half decades. This was apparently suggested by the two actors and introduces a subtext that’s both brave and problematic.

It could be argued that aligning homosexuality with outlaws and criminality only reinforces an idea that it is somehow deviant. Interestingly, Italy had abolished laws against same-sex relationships in 1890, around the era of the story’s setting, but the decriminalisation of same-sex sexual activity in the US had only begun in the 1960s, starting with Illinois state legislation, and wasn’t accepted across the nation until 2003! In the context of El Puro, it could also be interpreted as suggesting discrimination that reinforces marginalisation of minorities is what may’ve denied Gypsy and Cassidy access to societal acceptance, forcing them to become outcasts and eventually leading them to become outlaws. Though this doesn’t redress the problem of associating male homosexuality with violent misogyny. Many years later, Aldo Berti would make an autobiographical documentary for Sky TV in which he talks about his bisexuality.

Another big plus is the textured, often tenebrous cinematography resulting from a collaboration between the director and Antonio L. Ballesteros. On occasions the low light levels bring out the film grain to create a painterly texture that suits the almost baroque compositions of the night scenes. This style of naturalistic lighting was a welcome innovation for Italian cinema which had generally relied on bright, even illumination. Partly for stylistic reasons and perhaps due to these kinds of films being considered B Movies, filmmakers began to rely on more modest rigs, sometimes utilising just one or two lamps. The result, which has parallels with the noir style of the 1940s, would become a trait of Italian pulp cinema through the 1970s, helping late-era spaghetti westerns, gialli, and horror develop their distinctive look.

One element that doesn’t quite work is the score’s blatant pastiche of Ennio Morricone’s theme music for Sergio Leone’s Dollars trilogy. It’s been pointed out that prolific composer, Allessandro Allessandroni had worked with Morricone and even had a hand in those scores, so it’s only to be expected that he’d use a similar approach to associate El Puro with its hugely successful predecessors. However, it’s pretty certain that if Morricone had been hired as composer, he would’ve provided something entirely more sympathetic to the movie’s more sombre tone.

ITALY | 1969 | 98 MINUTES • 108 MINUTES | 2.35:1 | COLOUR | ITALIAN • ENGLISH

An assassin finds his conscience when he and his brother get involved in a plot to kill the leaders of a growing labour movement.

From the opening scenes, Wrath of the Wind / La collera del vento barely feels like a spaghetti western. It’s more like a 1930s gangster movie, as two hit men in dark suits gun down a dignitary of some sort in the forecourt of a grand public building. It’s clearly some kind of gangland assassination and introduces us to the killers, Marcos (Terrence Hill) and his younger protégé Jacobo (Mario Pardo). Spanish director Mario Camus cleverly exploits audience preconceptions by casting Hill in this ambiguous role, fully aware we’ll be swayed by his square-jawed, blue-eyed good looks and track record of playing good guys. He builds on this enigma as Marcos and Jacobo travel to their next job, arriving separately, in a farming community dominated by exploitative landowners who are beginning to have problems with their disgruntled workers.

On arrival, Marco is approached by the schoolmaster (Carlos Otero) who seemingly mistakes him for someone the village is expecting. It becomes apparent that the local gentry, led by Don Antonio (Fernando Rey) and his son Ramon (Máximo Valverde), have hired someone to quell dissent among their tenant farmers through some targeted terror tactics. But it turns out the villagers, organised by the schoolmaster and the blacksmith (Ángel Lombarte), have also hired a professional of their own. So, which side are Marcos and Jacobo working for? Are they on the same side? Are they playing both sides against each other? Or is there a third, anonymous agent in the mix?

Intrigue increases when Soledad (Maria Grazia Buccella), the mistress of the inn where Marcos is lodging appears to be covering for him and providing alibis when key players in the dispute are killed. Although she is already having an affair with the blacksmith, she also begins to have feelings for Marcos. Can he be redeemed by a woman’s love and the possibility of a settled life?

Of all the four films presented here, Wrath of the Wind has the most intriguing storyline but only wears the genre loosely. Because of its locations in Andalucia Spain, the exploitative elite wearing Spanish styles, and with a Spanish director at the helm, it’s been called a tortilla, or chorizo, western. But above all, Camus presents us with a political thriller that serves as a critique of Francoist Spain thinly veiled in metaphor. The primary inspiration came from the writings of Spanish intellectual Juan Díaz del Moral, particularly his 1929 book History of the Andalusian Peasant Agitations. It also echoes aspects of the 1930s Great Depression, but more explicitly the protest movements of the 1960s and the contemporary unrest as Italian student-worker coalitions unionised and occupied factories in the late 1960s, with workers sometimes resisting the demands of both unions and management.

SPAIN | 1970 | 106 MINUTES | 1.85:1 | COLOUR | ITALIAN • ENGLISH • SPANISH

A quartet of misfits go from sharing the same jail cell to embarking on a savage odyssey that will lead to torture, rape and cannibalism.

At this time, horror maestro Lucio Fulci was better known for his early musical comedies and giallo-style thrillers and just one previous western, Massacre Time (1966). He’d yet to earn his reputation as the ‘Godfather of Gore’ but there are a few scenes in The Four of the Apocalypse / I quattro dell’Apocalisse that presage his extreme ‘Gates of Hell’ sequence comprising Zombie Flesh Eaters (1979), City of the Living Dead (1980), The Beyond (1981), and The House by the Cemetery (1981). There’s certainly a horror aesthetic at work when a group of characters turn to cannibalism to survive, possibly inspired by the historic events of the Jamestown settlers who did eat their dead during the harsh winter of 1609.

However, the film’s setting is the late-19th-century and opens with the arrival of professional card-sharp Stubby Preston (Fabio Testi) in the town of Salt Flats, where he’s greeted from the train by the Sheriff (Donald O’Brien), who burns his marked decks and throws him in jail for the night with orders to leave the next day. That night, the town is attacked by a masked gang of vigilantes, resembling the Ku Klux Klan, who set about lynching most of the inhabitants, particularly those in the saloons and casino. The Sherriff does nothing to interfere and seems to have known the massacre was planned, perhaps even instigating it. The morning after, as he leads Stubby and his three cell mates through the aftermath, he explains that the town needed purging so that decent people could now move in. He releases his four charges from custody, giving them a cart and sending them away.

The film now follows a road movie format as the four unlikely companions get to know each other, overcoming their differences, eventually finding respect, and finally love. The three joining Stubby are young and pregnant prostitute, Emanuelle ‘Bunny’ O’Neill (Lynne Frederick), town drunk Clem (Michale J Pollard), and Bud (Harry Baird), a crazy young black man who believes he can commune with the dead. Apart from Bud, versions of these characters all feature in the 1869 short story The Outcasts of Poker Flats by Bret Harte, from which the screenplay draws heavily while significantly reworking the elements. Though it may be hard to believe, Fulci’s film isn’t as dark and pessimistic, which is super-surprising as he and screenwriter Ennio De Concini also weave in parts from another, just as tragic short story of Harte’s The Luck of Roaring Camp, published in 1868. The stories of Bret Harte had already been adapted into numerous westerns as well as musicals and operas.

The Four of the Apocalypse is a memorable, picaresque sequence of set-pieces that’s been compared to Dante’s Inferno or a journey through purgatory with some genuinely nightmarish imagery, including the ‘demonic’ presence of Chaco (Tomas Milian) who joins them for part of their journey, providing plenty of duck and hare with his dead-shot rifle skills before revealing himself to be a completely amoral bandit. I think the rest of the group start to worry when he captures a lawman who’d been pursuing them, strings him up and commences to flay him alive. Milian has explained that he based the character on the infamous cult leader, Charles Manson.

During one of the movie’s more hallucinatory intervals he distributes peyote and while the others are tripping, ties them up, rapes Bunny, and makes off with their wagon, horses, and supplies, leaving them to die… which they don’t. Instead, they continue their arduous journey on foot, with Stubby and Bud now carrying the injured Clem on a makeshift stretcher, first through a parched landscape and then through a deluge of Biblical proportions. They also come across the aftermath of Chaco’s sadistic raids in which he kills entire groups of settlers and pilgrims, including women and children. Stubby swears, more than once, that he will find and kill him.

All the main cast are great and play well off each other. This is particularly true in the scenes between Fabio Testi and Lynne Frederick who both manage some truly heart-rending moments. Harry Baird also does a good job of juggling Bud’s innocence and insanity so that we still root for him, even after some pretty transgressive acts. It took me a few moments to place the actor as one of the recurring characters, Mark Bradley, in UK TV series UFO (1970-71).

Eventually, Stubby and Bunny hook up with a travelling preacher (Adolfo Lastretti) who guides them to a snow-bound mining town where Bunny’s baby can be delivered. The set was a left-over from Fulci’s previous production, Challenge to White Fang (1974), built in the Austrian Alps near the winter sports resort of Bad Mitterndorf. Although surprisingly cohesive, each section of the narrative has its own a distinctive feel achieved by the beautiful, poetic, often psychologically sympathetic cinematography of Sergio Salvati who would become Fulci’s repeat collaborator. This chapter introduces a lighter tone where the rough outcasts of the town begin to mend their ways in the presence of an expectant mother and newborn baby who brings hope for the town’s future. That’s before it all takes a sinister turn once more and heads toward its unpredictable, ultimately satisfying finale.

ITALY | 1975 | 104 MINUTES | 1.85:1 | COLOUR | ITALIAN • ENGLISH

directors: Paolo Bianchini (Dead) • Edoardo Mulargia (Puro) • Mario Camus (Wrath) • Lucio Fulci (Apocalypse).

writers: Carlos Sarabia (Dead) • Fabrizio Gianni, Ignacio F. Iquino & Edoardo Mulargia, Fabio Piccioni (Puro) • Manuel Marinero & Mario Camus (Wrath) • Ennio de Concini & Lucio Fulci (Apocalypse).

starring: Craig Hill, Lea Massari, José Manuel Martín, Andrea Bosic & Licia Calderón (Dead) • Robert Woods, Aldo Berti, Marc Fiorini, Mario Brega, Rosalba Neri, Fabrizio Gianni & Maurizio Bonuglia (Puro) • Terence Hill, Maria Grazia Buccella, Mario Pardo, Máximo Valverde, Carlo Alberto Cortina, Ángel Lombarte & Fernando Rey (Wrath) • Fabio Testi, Lynne Frederick, Michael J. Pollard, Harry Baird & Tomas Milian (Apocalypse).