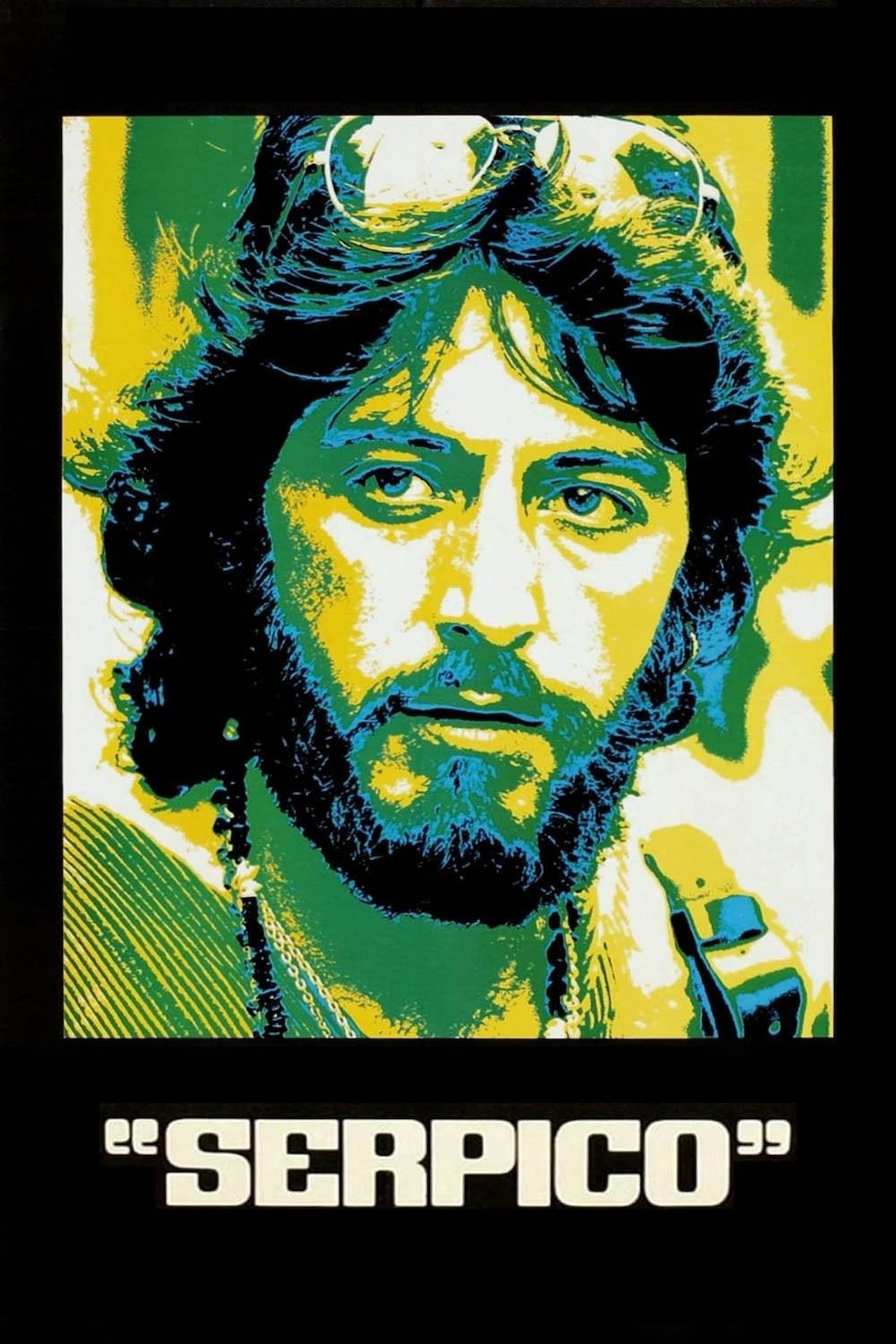

SERPICO (1973)

A young NYPD recruit in the 1960s struggles to expose the corrupt practices of other cops.

A young NYPD recruit in the 1960s struggles to expose the corrupt practices of other cops.

Gritty realism was the stock-in-trade of early-1970s US cop films, and Serpico is one of the grittiest. Indeed, its grimy, messy New York City streetscapes are among the film’s most memorable elements. However, it’s as different as can be from films like The French Connection (1971) or Dirty Harry (1971) in its portrayal of a police officer protagonist who’s scrupulously law-abiding but not a traditional Hollywood hero: Al Pacino’s Frank Serpico is, frankly, annoying, self-pitying, obsessive, and utterly dysfunctional in his social interactions.

There’s also very little actual police work in Serpico, to the point it’s almost the opposite of a cop movie. Despite its focus on a criminal investigation into corruption within the New York Police Department (NYPD), the presence of “ordinary” bad guys is surprisingly sparse. And even when they do appear, it’s mostly to illustrate their unhealthy relationships with the police.

Serpico is a surprisingly weak movie in many respects, given its enduring fame. Sidney Lumet’s film is built entirely around the character of Serpico and is inseparable from the image of Pacino playing him, with his increasingly wild hair and grungy dress. However, perhaps because his real-life equivalent was very much alive, and still is, it never gets far beyond the surface of the character. We witness his actions, and his various eccentricities are paraded as if to emphasize his unusualness, but we never truly understand his motivations or the person he is.

While it may not fully deliver, the film does have some memorable moments and performances, as well as playing a significant role in the careers of Al Pacino and Sidney Lumet, and occupying an intriguingly ambiguous position in the genre’s development.

Pacino is virtually the only person from Serpico who remains well-known today. The film helped to cement his reputation after The Godfather the previous year; earning him his second Academy Award nomination, with Lumet’s Dog Day Afternoon (1975) later providing another.

For Lumet, Serpico was not only one of many films that showcased the powerful impact of New York City settings—having utilized the city’s locations extensively in previous films like The Pawnbroker (1964) and The Anderson Tapes (1971)—but it also marked a recurring theme of corruption within law enforcement, a theme he revisited in later works such as Prince of the City (1981), Q&A (1990), and Night Falls on Manhattan (1996).

Far from merely being a conventional cop-and-mean-streets movie, Serpico deftly weaves together several distinct threads of 1970s US cinema, often in unexpected ways. By contrast to the rough-and-tumble lawmen epitomized by Dirty Harry’s Harry Callahan and The French Connection‘s Popeye Doyle, Serpico’s unwavering integrity stands as a stark antithesis. Yet, as an individual, Serpico transcends even these unconventional archetypes. He’s neither a traditional detective hero nor a revisionist cop protagonist playing fast and loose with the law.

In a broader sense, Serpico also shares a strong affinity with another significant genre of 1970s cinema that extends beyond the realm of law enforcement: movies like Three Days of the Condor (1975), Capricorn One (1977), and Coma (1978), where a valiant outsider or partial outsider attempts to expose malfeasance within the system. The apogee of this trend might be considered All the President’s Men (1976), and it’s noteworthy that Serpico was released just as the Watergate scandal was emerging. Corruption within a revered institution had never been more topical.

That said, Serpico is more about the personality than the details of the issues and events it depicts. Lumet had replaced filmmaker John G. Avildsen, who wanted to concentrate more on the political aspects of NYPD corruption and its exposure. While Serpico doesn’t ultimately succeed in this, leaving much of the central character unexplored, it’s an interesting example of a film that appears to be a cop movie but is something quite different. It’s easy to imagine Serpico set in a completely different context, such as a large corporation, and still retain the film’s essence, albeit not one so closely based on truth.

Serpico is based on the book of the same name by New York crime journalist Peter Maas, published in 1973 and written with the collaboration of its subject. It opens near the end of its story, with a wounded Serpico being rushed to the hospital in a police car (Pacino looking as much like a suffering Jesus as he ever has); soon, as we see the police department’s reactions to his shooting, we will realize that Serpico is important—but not yet why.

The bulk of the movie tells us that, technically in flashback. Whether this is intended to depict Serpico’s own recollection of the events leading up to his shooting or simply Lumet’s presentation of them remains unclear. While the flashback doesn’t reveal any information that Serpico wouldn’t be privy to, it doesn’t suggest he’s an unreliable narrator.

In any case, the main story begins 11 years earlier (however, the time that passes doesn’t feel quite as long in the film), with the young Serpico graduating from the police academy and listening to an inspiring speech about the fight against crime before starting as a uniformed officer on patrol. Though naive (requesting a different menu item when a cafe owner offers him and his partner free food), he’s also enthusiastic, vying to take a call that they could easily skip; this leads to the first real meat of the movie, a tense, kinetic sequence where Serpico and his partner interrupt a gang rape, chase the perpetrators, and arrest one of them.

In the subsequent police station scene, Lumet’s film sympathises with the victim. But it also sides with the young man (Franklin Scott) as he endures a violent interrogation at the hands of an officer ominously nicknamed Muscles (Hank Garrett); Serpico leaves the room as the beating takes place, later informing the boy “that’s not my kind of fun” upon taking him for a cup of coffee and engaging in gentler chat, ultimately persuading him to turn in his friends in a manner that more brutal treatment failed to elicit.

Although he’d only just been portrayed as wet behind the ears in the previous scene, Serpico is perhaps unconvincingly assured in this one-to-one interaction with the young suspect. However, this serves an important dramatic function in distinguishing him from his fellow officers. The exact issue that’ll permanently separate them becomes clear soon after: it’s not the treatment of prisoners, but the other cops’ endemic rule-breaking.

The first indication of this is when others insist on taking credit for his arrest. Shortly thereafter, Serpico is offered money in an envelope, and this leads him into a years-long crusade against corruption within a department where some officers pocket hundreds of dollars a month in bribes. This practice is so deeply ingrained that Serpico, rather than the bribe-takers, appears to be the deviant one. “Who can trust a cop who don’t take money?” one officer questions; “I feel like a criminal ’cause I don’t take money,” Serpico later confesses.

Meanwhile, time passes, signified by Pacino’s increasingly shaggy appearance—the movie was shot in reverse chronological order so he could start filming with long hair and end it with a shorter cut—as well as his updated wardrobe and glimpses into his personal life. All of these changes further distance him from his colleagues. While other “undercover” cops wear formal civilian clothing that makes them stick out as much as a uniform would, Serpico convinces his superiors that he should dress as if he belongs on the street (and as a result, he’s nearly shot when someone mistakes him for a criminal, perhaps a symbolic moment).

He also sings along to opera in the car, buys a puppy, keeps a pet mouse, goes to Spanish literature classes, and studies ballet—all of this very atypical for the conservative, uber-masculine NYPD. It’s no surprise that at one point he’s accused, on the flimsiest of grounds, of being a “fag”.

Lumet films all this in a very straightforward, almost fly-on-the-wall style. It’s not a movie where the direction intrudes at all visually, even if it’s thoroughly a Lumet film in thematic terms—and though the widely-criticised score by Mikis Theodorakis can be excessively sentimental (especially in the hospital section, and in a local-colour street scene with kids playing in the water from a fire hydrant) at least its more jazzy passages work better than the Godfather-tinged quasi-Italian music.

For the most part, the screenplay and performances are allowed to speak for themselves, enhanced but not overpowered by the New York ambience. And at times, they do shine. Several small scenes stand out, such as Serpico’s spur-of-the-moment purchase of a puppy from a couple of kids on the street, or the distribution of marijuana joints to a roomful of officers at the station to familiarize them with the then-unfamiliar drug. While few, the action sequences are executed with aplomb.

Pacino is undeniably the central figure in the cast. The entire movie revolves around him and his experiences; although he occasionally verges on overacting in a Method style that was prevalent at the time, he still convincingly embodies his character, gradually revealing the man’s inner turmoil (his angriest lines are those that convey his turmoil).

Although the script doesn’t delve deeply enough into Pacino’s portrayal of Serpico, and other characters are even less developed, there are still some persuasive performances. And the absence of other stars, or even particularly noticeable faces, further helps to establish a sense that it’s Serpico against the world.

Tony Roberts, playing Bob Blair, one of the few to stand by Serpico, stands out prominently. More politically astute than the Pacino character, he frequently serves as a voice of reason, and at one juncture criticizes Serpico for being unrealistic; a criticism which, at least in today’s context, might resonate with many audience members’ reactions. (Blair was based on the real-life David Durk; Serpico garnered more support within the police department than the film explicitly portrays, and not every single officer was corrupt, despite its implications—another example of how Lumet and the writers choose not to delve too deeply into nuances.)

Norman Ornellas brings scenes to life in his brief role as Rubello, a cop full of nervous energy whose cheerfully corrupt approach to his job partially conceals a vicious side. Richard Foronjy also grabs one’s attention as the dapper gangster Corsaro; Serpico arrests him but soon finds him chatting and joking with the rest of the squad. Edward Grover as Lombardo, is also great as a sympathetic commander for Serpico who appears towards the end and is one of the few likeable characters.

However, nearly every character in the film exists solely to illustrate Serpico’s dilemmas or, in rare instances, to reflect his views. This applies not only to the police officers but also to his girlfriend Laurie (Barbara Eda-Young), who, despite having a biggish part, is even more devoid of character than the Pacino girlfriend played by Karen Allen in William Friedkin’s Cruising (1980). In fact, in a film so dialogue-driven and often characterized by close-ups, there are barely any “characters” in the true sense; most of them consist entirely of their actions, with minimal or no effort made to show perspective or motivations.

Despite the film’s superficiality, it did well at the box office, no doubt due to the presence of Al Pacino and the topicality of the real Serpico. While it didn’t reach the heights of The Exorcist, The Sting, or American Graffiti, it still performed quite well. It also received critical acclaim, with Pacino and the screenwriters being nominated for Oscars. (Although they didn’t win, Pacino did receive a Golden Globe and the screenwriters were awarded a Writers Guild award.)

Critics were mostly positive as well, except where Theodorakis’s score was concerned. Vincent Canby of The New York Times called it “a galvanizing and disquieting film,” singling out Pacino’s “splendid performance in the title role” and the “tremendous intensity that Mr Lumet brings to this sort of subject.” However, he also rightly noted that the film’s major shortcoming was its lack of exploration of the character. Pauline Kael of The New Yorker acknowledged it was “far from perfect” but still considered it “a hugely successful entertainment.”

A short-lived NBC TV series in 1976-77, starring David Birney in the title role and preceded by a movie-length pilot called Serpico: The Deadly Game (1976), brought Frank Serpico to the screen once more. However, it’s Lumet’s film and Pacino’s performance in it that remains most widely remembered, even more so than the real man or the book by Maas.

Yet it also remains a film with a huge hole at its heart: who is he? Why is he doing this? Lumet claimed that “there’s a lot of me in Serpico” (the character) yet that seemingly didn’t encourage him to fill out the man.

In a scene set at an artsy party, Serpico encounters individuals styling themselves as novelists, poets, and other literary figures, despite their mundane day jobs. The implication is that Serpico stands apart as the only “real” person, simply identifying himself as a cop. However, this supposed authenticity remains elusive. Despite his tormented demeanour, as film critic Pauline Kael wrote, there’s really “no pain” in the film. We’re unable to empathize with Serpico because the movie never reveals his true self. Instead, he appears to inhabit a fantasy land much like the aspirational literary types he encounters.

There is also a risk that his righteousness comes across as inflexible or selfish. Even when he gets the investigation he’s been calling for, he’s grumpy, resentful, and unhelpful, insisting it will only be desultory. And when he (who had eschewed violence with the young suspect at the beginning of the movie) becomes violent himself at home, it’s very easy to see this as an expression of a man who can’t bring himself to compromise, rather than a reasonable man pushed to the limit.

As Pauline Kael also noted, “The movie turns this hero into a mere freak.” Despite some undeniable strengths in performances, dramatization, and atmosphere, Serpico fails to fully explore its subjects (human, institutional, or legal) to their fullest potential. While Sidney Lumet was undoubtedly capable of misjudgment—as evidenced by The Anderson Tapes, a film that is both bizarre and rather dull—Serpico remains a standout performance for Al Pacino, even if it falls short of Lumet’s best work.

ITALY • USA | 1973 | 130 MINUTES | 1.85:1 | COLOUR | ENGLISH • ITALIAN • SPANISH

director: Sidney Lumet.

writers: Waldo Salt & Norman Wexler (based on the book by Peter Maas).

starring: Al Pacino, John Randolph, Jack Kehoe, Biff McGuire & Barbara Eda-Young.