JAWS (1975)

When a killer shark unleashes chaos on a beach community, it's up to a local sheriff, a marine biologist, and an old seafarer to hunt the beast down.

When a killer shark unleashes chaos on a beach community, it's up to a local sheriff, a marine biologist, and an old seafarer to hunt the beast down.

In a film as near-perfect as Jaws, it’s almost impossible to pick out highlights. With a few minor exceptions, every scene helps progress a story that’s as relentless as it is simple; finely-crafted in the tiniest details but never self-conscious about them.

The beginning is as good a place to start as anywhere. The opening few minutes of Jaws illustrate why it remains such an effective movie 45 years after its release in the summer of 1975, even for those who’ve seen it more times than they can count in an era when VFX has vastly improved.

The first shot is underwater, creeping through murk and ocean flora. It’s teasing audience who know they’re watching a movie about a shark. The soundtrack is ominous thanks to John Williams’ famous Jaws theme, one forever associated with sharks now. And there’s even a touch of shrieking strings, bringing the shower scene from Psycho (1960) to mind… and this segues directly into a young guy playing the harmonica at what seems to be a college kid’s beach party.

The sea felt sinister, but now we’re on land, so we must be safe, hearing jollier music… right?

Already the fundamental power of Jaws is clear: it’s not a story about a shark but a story about water. A liquid that covers most of the planet and in which humans are almost completely helpless. The shark is more of a convenience for the narrative; a way of concentrating that threat into deeper unease—rather like how the fire in The Towering Inferno (1974) was a vivid manifestation of wider fears about technological hubris.

From this late-night party emerge two young characters, Chrissie (Susan Backlinie) and Tom (Jonathan Filley), who leave the group to go for a swim. Chrissie strips off and enters the sea (looking for all the world like a coed unwisely taking a shower in one of the 1980s slashers Jaws helped influence), while Tom collapses drunk on the beach.

Next, in one of the most striking compositions of a film where the photography’s always careful despite looking naturalistic, Chrissie dives beneath the surface… and as she does so her arm rises above the water, resembling a shark’s dorsal fin, symmetrically balanced in the frame by a buoy. We notice, perhaps, just how tiny both her arm and the buoy are compared with the sea. Now we cut to the underwater again, but this time the implications are unmistakable: it’s a shark’s point of view, but we don’t yet see the creature itself.

Certainly, we don’t see this shark while it eats Chrissie. We mostly see the ocean. The buoy to which she briefly clings is a pathetic and useless substitute for land, and the shot foreshadows the way Roy Scheider’s character likewise clings to the mast of a sinking ship in the climax: another futile attempt by humans to impose their will on the sea.

Tom, meanwhile, is still on the shore, oblivious to Chrissie’s plight. The gentle remnants of a wave wash over him as if warning us that even those on the land aren’t going to be safe from the water for long.

But the next scene is as different as could be. It’s now daytime, the colours are bright and pastel and the mood domestic as police chief Brody (Scheider) and his wife Ellen (Lorraine Gary) chat away. “Somebody feed the dogs,” she says, and there’s a distinct pause after the word “feed” as if alluding back to what we’ve just watched. The Jaws of myth (and marketing) may be a terrifying thriller, but it’s also a film brimming with humour.

This vein of comedy continues as their son (Chris Rebello) enters the house with a bleeding hand. “I got hit by a vampire!” he exclaims happily. (It remains a mystery why he says hit and not bit), then asks his parents “can I go swimming?”

And in just those couple of lines, screenwriter Carl Gottlieb and promising young director Steven Spielberg have managed to casually sow two more seeds in the audience’s mind: the idea this shark is a monster (something almost supernaturally lethal like a vampire) and the idea it will soon get personal for Brody. All this has taken around six minutes, and it’s a rarely paralleled masterpiece of an opening.

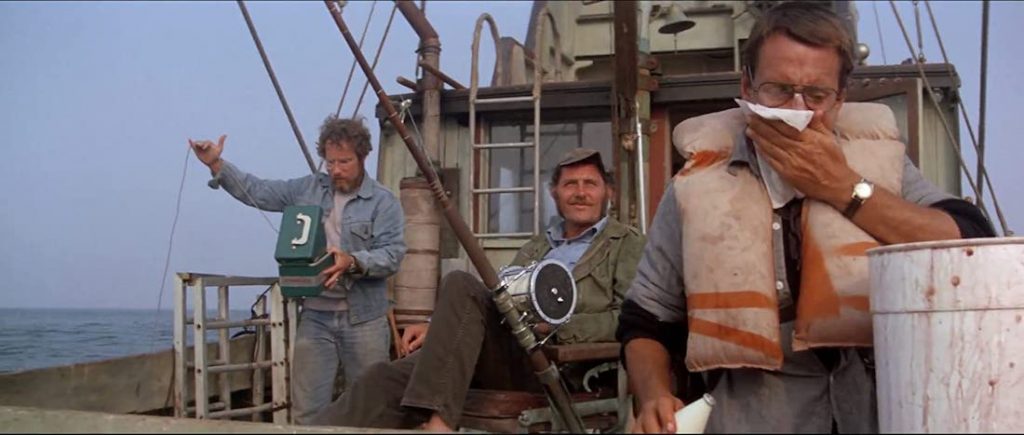

Indeed, what makes Jaws such an achievement is that it seems so uncomplicated and unfussy on the surface despite being so meticulously constructed. It’s mostly driven by a forward narrative rather than by contemplation (as Gottlieb said, “nobody but the story was the star”), and though the three principal characters—chief Brody, scientist Matt Hooper (Richard Dreyfuss) and shark-hunter Sam Quint (Robert Shaw)—never feel unbelievable, no time’s wasted in giving them complex motivations or backstories. Those emerge from their performances.

It’s also a virtually non-stop film where only one sequence is questionable—the flabby beginning of the 4th of July beach scene, which doesn’t add much to what audiences already know. Apart from that, every moment contributes to the whole endeavour; whether to push the narrative forward, crank up the tension, lull audiences into false security, or develop characters. Yet it never feels hyperactive. In fact, despite the urgency of the situation it portrays, most of the time it has the same relaxed atmosphere of a summer beach resort where it’s set.

Indeed, two of the most powerful scenes are among the stillest: the confrontation between Brody and a woman who’s lost her child to the shark (where the town’s hubbub seems to cease to focus solely on her fury), and Quint’s account of a shark attack on shipwrecked sailors during WWII.

The plot is well-known and straightforward. After the attack on Chrissie, the shark strikes three more times off the fictional town of Amity, New England. (The movie was actually shot in Martha’s Vineyard near Cape Cod, with nearly all the ocean scenes shot offshore using real boats). Chief Brody, a newcomer to both his job and community, wants to close the beaches to protect people, but the mayor (Murray Hamilton) initially won’t let him, concerned about the effect on tourism.

Eventually, it’s accepted even by the hesitant mayor that this shark must be hunted down and killed. And so, just a few days after the attack on Chrissie, Brody sets off in a small craft (the Orca) with shark expert Hooper an irascible sailor Quint. The rest is cinematic history….

Broadly, it’s the same plot as Peter Benchley’s best-selling 1974 novel but trimmed down. In the book, for example, Ellen and Hooper have an affair, the mayor has links to organised crime, and class issues loom larger. In Spielberg’s film, there’s certainly a class-conflict aspect to working man Quint’s relationship with the wealthy and educated Hooper, but the book and film remain different enough that Spielberg reportedly asked Dreyfuss not to read the source material.

In other words, Jaws the movie directs its attention more single-mindedly to the water than Jaws the book, with its political and sexual shenanigans. The water is a constant, usually shown or being discussed even during the moments on terra firma. The shark barely appears at all before the climax, and nor are there as many attacks as its reputation might suggest.

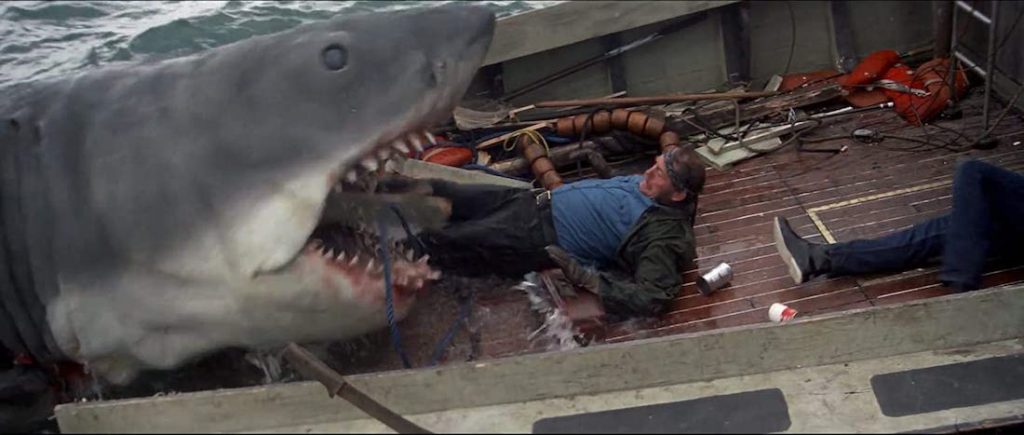

The creature strikes five times in all, with the fatalities including a child and a dog (surprising for Hollywood tastes), but Quint’s is the only death we actually see in detail. This relatively low body count and restrained gore helped get Jaws a PG-certificate when it was released in the US, but it’s a stretch to consider this family-friendly even today. At the time, Charles Champlin of the Los Angeles Times warned that “Jaws is too gruesome for children and likely to turn the stomach of the impressionable at any age.”

Surely the blood and guts are in the service of deeper meaning, though? At the time of its release, many certainly thought so. Yet the range of interpretations conferred on Jaws perhaps reflected the preoccupations of the mid-1970s more than anything inherent in the film itself: the shark allegedly represented the silent and deadly Viet Cong, or Communism, or phallic male aggressiveness, or economic decay, or even nuclear weapons. The latter is an especially unpersuasive theory, supported only by one tenuous connection–that the USS Indianapolis, on which Quint had sailed in the war, delivered parts of the bomb that fell on Hiroshima.

The land story, meanwhile, was suggested by some to recall Watergate, perhaps helped by Hamilton’s vague resemblance to President Nixon. (More recently this same fictional mayor’s reluctance to close the beaches has been compared to US governors unwilling to impose social lockdown during the COVID-19 pandemic.)

Much more persuasive is the position of critic Antonia Quirke, who argues that Jaws doesn’t have any special meaning. Just as the shark kills and eats without any subtle motive, the makers of Jaws entertain simply because that’s what they do. That doesn’t mean it’s a dumb film. Indeed, the absence of any characteristics in the shark apart from hunger is a stroke of genius; nobody can ever accuse Jaws of anthropomorphising the way that they might King Kong, for example, though it does manipulate our bloodthirsty selves into rooting slightly more for the shark than for the people in the first half, at least.

Gottlieb, Spielberg, and a team including cinematographer Bill Butler extract a huge amount from the potent land/sea contrast, too, even extending it to water/air contrasts with some shots that are partly beneath the surface and partly above. More than half the movie is set in the town of Amity, so most of the time the sea is out there, threatening but not too familiar. This heightens the tension in the second half after the Orca sets out, and indeed the real terror at the end is not that the shark is prowling, but that the boat is sinking.

Even the three main characters are differentiated by their approach to the water. Quint is the old salty sea dog, Hooper is the scientist fascinated by the sea but detached from it (symbolically so by his shark cage), and Brody is downright afraid of the water, giving him the clearest arc in the film as he grapples with his fear.

The three main players meld beautifully in these roles, much of their success ironically coming from the long delays in filming caused by the malfunctioning mechanical shark. All from theatre backgrounds, they were able to improvise and develop their characters while waiting for shooting to resume, despite some offscreen clashes (especially between Shaw and Dreyfuss).

None of the actors was a major star in ’75, though Scheider had come to prominence in William Friedkin’s The French Connection (1971), while Dreyfuss had received award nominations for The Apprenticeship of Duddy Kravitz (1974) and, before that, George Lucas’s American Graffiti (1973). But the characters they create are among the most memorable of the decade, and of Spielberg’s oeuvre.

Quint may be the most boldly drawn—almost a parody, singing “yo ho ho and a bottle of rum” as the Orca sets sail. Like many Spielberg characters, he’s obsessive. One of the best-known scenes in Jaws tries to explain that obsession as Quint recalls being adrift in the sea with fellow sailors for days after the sinking of the Indianapolis in 1945, the survivors gradually picked off by sharks.

There’s still controversy about who wrote this iconic speech because it’s not in the novel, and there’s an intriguing subtext to it as well. Several details Quint mentions are incorrect or self-contradictory. Although the Indianapolis incident undoubtedly occurred, this raises the question of whether such a teller of tall tales was really there to witness it…

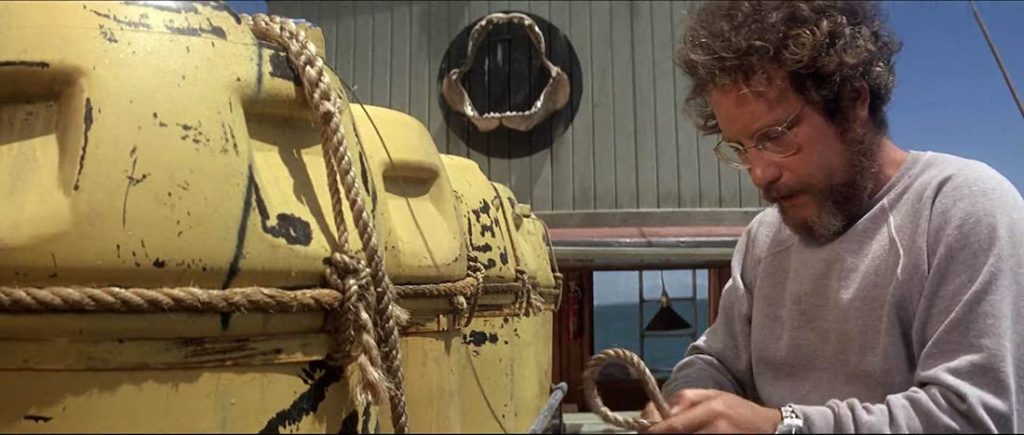

At other times Jaws builds character through briefer touches; for example when Hooper struggles to control his shock after seeing the chewed-up remains of Chrissie in the morgue. And particularly strong insights come from contrasts in the way they’re portrayed. Consider, for example, how Brody is such a meek klutz in an Amity shop buying sign-painting equipment before closing the beaches, while Quint (in a deleted scene available on YouTube) completely dominates another shop that he enters to buy piano wire. Or consider how the seafaring novice Brody is still learning to tie a knot at exactly the same moment the old hand Quint is strapping himself into his chair on the Orca, after noticing a tiny movement in his line.

The leads are inseparable from Jaws in the collective memory now. It would surely have been a lesser movie with Jan-Michael Vincent as Hooper (as the studio wanted), and would’ve sunk without a trace had Charlton Heston succeeded in getting the part of Brody. But some other actors under consideration, like Jon Voight as Hooper and Robert Duvall as Brody, might have become part of the legend too.

Few others stand out, apart from Hamilton’s wonderfully insincere mayor with his lurid jackets, and many smaller parts were taken by Martha’s Vineyard locals. Screenwriter Gottlieb appears as the town’s newspaper editor, novelist Benchley cameos as a TV reporter, while Spielberg’s voice can be heard as a coast guard.

And then, of course, there is the titular star: the mechanical shark nicknamed ‘Bruce’ after Spielberg’s lawyer, a relatively realistic Great White though sleeker than any living animal its length would be.

The unreliability of the three complex shark models and budget overspends, with a planned schedule of 50-odd days growing to nearly 160, led the film to be nicknamed Flaws. But the setbacks were perhaps crucial to its success. Not only did they give the actors time to hone their performances, but it’s also because filming with Bruce the shark was so difficult that it was rarely seen until the ending. Instead it existed mostly in everyone’s imaginations, stoked by Williams’ iconic theme.

Flaws wasn’t expected to be a major success. “It was considered a big B-movie”, Gottlieb recalled. Universal had pinned more hopes on The Hindenburg (a now nearly-forgotten disaster movie redeemed only by a gripping closing sequence). Spielberg himself was still a relative newcomer to feature films, and while Duel (1971) and Sugarland Express (1974) had been well-received, neither was a big hit. Indeed, Spielberg worried that Jaws might be too similar to Duel and could unhelpfully pigeonhole him as a “shark-and-truck director.”

But scepticism about its fortunes was soon replaced by huge confidence, and the heavily-advertised Jaws opened in the US on more than 400 screens simultaneously—a remarkable statistic back then, if small by the standards of the modern blockbusters it became the template for. It became the highest-grossing movie of all time, beating The Godfather (1972) and The Exorcist (1973), although Star Wars (1977) trumped it a few years later.

Jaws got nominated for ‘Best Picture’ at the Academy Awards, too, though it only picked up three Oscars. Alongside its ‘Best Sound’ award, Verna Fields won for ‘Best Film Editing’ (it was in her swimming pool that the famous head-in-the-boat scene was shot after principal photography had finished and audience previews had started), and Williams for ‘Best Original Dramatic Score’. His music for Jaws is now considered a high point of film composing. Not always foreboding, it’s sometimes summery in an Aaron Copland style, sometimes exuberantly dramatic, and works so well that he went on to score nearly all Spielberg’s subsequent movies.

Critics were largely enthusiastic about Jaws, many singling out its humour as well as its thrills. “It’s a film that’s as frightening as The Exorcist, and yet it’s a nicer kind of fright, somehow more fun because we’re being scared by an outdoor-adventure saga instead of by a brimstone-and-vomit devil,” wrote Roger Ebert. “You will recognize it as nonsense, but it’s the sort of nonsense that can be a good deal of fun,” agreed Vincent Canby in The New York Times. It was “funny in a Woody Allen way,” said Pauline Kael in The New Yorker.

There were three sequels, none directed by Spielberg, though he had wanted to do one based on Quint’s Indianapolis anecdote. The first of them, Jaws 2 (1978), is workmanlike enough but ultimately a weaker retread of the original, emphasising the slasher idea with a focus on a group of teens.

For Jaws 3-D (1983), the first movie’s designer, Joe Alves, took the directorial reins and Richard Matheson (who’d written Duel but turned down Jaws for being too similar) wrote the screenplay. Reviews of that one were poor, and by the time Jaws: The Revenge (1987) arrived in cinemas, the franchise had sunk into ludicrousness, with a Great White shark somehow following the Brody family from Amity to the Bahamas!

As significant as its own sequels are the films Jaws helped influence. And not just the obvious cash-ins like Piranha (1978), Tentacles (1977), and Orca (1977), but a multitude of other killer-creature flicks like Grizzly (1976) and Day of the Animals (1977). In the latter two, Susan Backlinie (who played Chrissie in Jaws) again plays the first victim! She also appeared in Spielberg’s own mini-Jaws spoof, as part of his flop comedy 1941 (1979).

Jaws’ impact wasn’t limited to the screen. Time magazine called the 1975 season “The Summer of the Shark”. Toothy merchandise of every kind proliferated. The Killer Shark arcade game seen at the beginning of Jaws’s 4th of July scene turned out to be prescient. Universal opened its first Jaws theme-park ride in 1976. The movie thrust sharks into the centre of pop culture discussion, in much the same way Spielberg’s own Jurassic Park (1993) did with dinosaurs nearly 20 years later. Hooper’s description of “an eating machine, a miracle of evolution” could equally well apply to the T-Rex.

And, just as Hamilton’s mayor had warned, beach resorts suffered from low attendances!

Inevitably, the huge literature on Jaws seeks to identify its forerunners as well as its successors. There are the obvious monster movies, like Creature from the Black Lagoon (1954), as well as a distinct element of the Western genre—Gottlieb even compares Jaws to “High Noon, pumped up” with its lone sheriff going out to confront evil. Beyond the cinema, Henrik Ibsen’s 1882 play Enemy of the People, with its nervous small-town mayor, and Herman Melville’s 1851 tale of whale-obsession Moby-Dick are often cited.

These influences are undoubtedly real. Jaws, unlike the shark, didn’t appear out of thin air. But they aren’t why it works so well. The actors are great, the script makes every line a valuable contribution, the action sequences are exciting, the pacing is astutely judged, and the shark actually isn’t terrible even by the high standards of our photorealistic CGI era.

No, above all, this movie succeeds because of how Spielberg hones in so ruthlessly on connecting audiences through empathy, amusement, anticipation, apprehension, and shock. 45 years and innumerable viewings later, the ‘head in the boat’ shot still makes you jump. And that’s the point of Jaws: it convinces you there’s something nasty out in the water, where we don’t belong.

USA | 1975 | 124 MINUTES • 130 MINUTES (EXTENDED) | 2.35:1| COLOUR | ENGLISH

I am indebted to the following resources: Antonia Quirke’s BFI Modern Classics • Nigel Andrews’ Bloomsbury Pocket Movie Guides • Carl Gottlieb’s The Jaws Log • Patrick Jankiewicz’s Just When You Thought it Was Safe: A Jaws Companion • Molly Haskell’s Steven Spielberg: A Life in Films.

director: Steven Spielberg.

writers: Peter Benchley & Carl Gottlieb (based on the novel by Peter Benchley).

starring: Roy Scheider, Robert Shaw, Richard Dreyfuss, Lorraine Gary & Murray Hamilton.