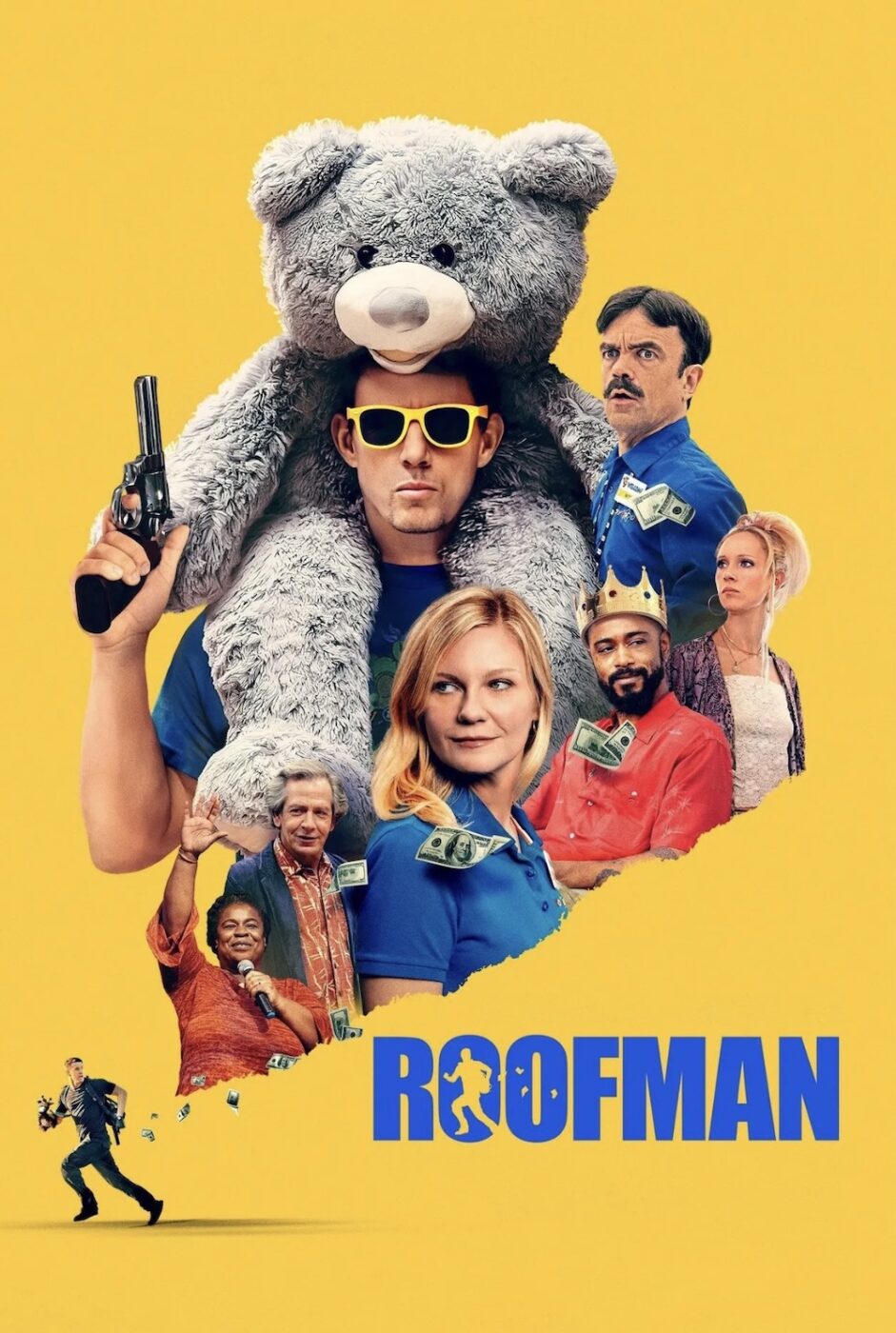

ROOFMAN (2025)

A charismatic criminal, while on the run from the police, hides in a hidden space of a toy store.

A charismatic criminal, while on the run from the police, hides in a hidden space of a toy store.

The year is 1998. Just down the street from a Blockbuster Video, Beanie Babies and Tickle Me Elmo adorn the shelves of a Toys “R” Us while Windows 98 hums noisily in the store manager’s office. That nostalgic overload takes centre stage in Derek Cianfrance’s Roofman, based on the life story of criminal Jeffrey Manchester (Channing Tatum), who took on the nickname. Cianfrance (Blue Valentine) uses that late-1990s haze and the bright consumer fantasy of the era as a backdrop for a story considerably darker in tone.

Manchester became known as ‘Roofman’ by entering businesses—mostly McDonald’s restaurants—through their ceilings, cleverly sidestepping alarm systems. The film walks a daring line in trying to paint a picture of what kind of man Jeffrey is. In the opening sequence, he wobbles a firearm while robbing a McDonald’s and locks a few employees in a freezer, making sure they all have jackets in a moment played for uneasy laughs. It’s a scene meant to quickly establish him as a good guy doing a bad thing. The whole film hinges on the audience’s willingness to buy into this notion—forgetting, ignoring, or forgiving that he’s committing a string of serious crimes.

Roofman’s bad deeds catch up to him when police chase him from his daughter’s birthday party and eventually track him down. A judge’s decision makes it clear they can only prove one McDonald’s break-in, though they strongly suspect him of many others. Somehow this still earns him a 45-year sentence. For the crimes shown on screen, it’s a baffling punishment, and anyone thinking too hard about it may conclude that the real-life events were harsher than what’s portrayed. A certain degree of suspended disbelief is required for the story to work at all.

One theme the film drives home, whether it intends to or not, is that of confinement. Not only is the main character an escaped prisoner, but he’s a prisoner in his own life. After he breaks out, the first thing he does is voluntarily lock himself inside a Toys “R” Us, serving a longer sentence there than in the prison he fled. When he finally ventures out, his first stop is a church, where he’s ushered in, seemingly against his will, and feels socially obligated to stay. It’s a reminder that one doesn’t have to be behind bars to be trapped. Freedom is available to Jeffrey at every turn, yetsomething always keeps him from choosing it. It’s symbolic of people stuck in lives they’re unhappy with but unwilling to change.

Much of the film unfolds in that toy store during the busy holiday season. Jeffrey builds a hidden living space behind a wall, steals what he needs, spies on employees with baby monitors, and eavesdrops on their conversations. There are layers of irony in play with Jeffrey hiding out in a Toys “R” Us. Set aside the name of the chain’s mascot, Geoffrey the Giraffe, and consider the first line of its famous jingle—a line etched into the minds of most millennials: “I don’t want to grow up.” A man on the run from life’s basic responsibilities taking refuge in a place built for children is poetry writing itself. In hindsight, the store was as doomed as the man hiding inside it. Toys “R” Us would collapse in 2018 under the weight of its own nostalgia and debt, leaving his temporary refuge as one more reminder that even childhood joy isn’t recession-proof.

Channing Tatum’s come a long way since his Step Up (2006) days. Once cast primarily for his good looks and charm—with line delivery that audiences often overlooked—he found his footing in comedy with Phil Lord and Christopher Miller’s 21 Jump Street (2012). In the decade since, his acting has matured with each new role. Here, he fits perfectly as the “bad guy you’re supposed to root for anyway.” He brings a goofy charm that works for the character, but he struggles in several key moments. Ironically, the romance—the kind of role that launched his career—is where he falters most.

While spying on the daily lives of store employees, Jeffrey develops feelings for Leigh (Kirsten Dunst), a recently divorced mother of two. He concocts a plan to meet her outside the store, and the two begin a clunky, forced romance. Dunst is not at fault; in fact, she delivers arguably the film’s best performance. Her accent can be a bit distracting, but there’s genuine emotional weight to her character. Unfortunately, she and Tatum share no real chemistry. Their relationship feels obligatory, as though it were a box to check on the screenplay’s to-do list. It moves fast—almost uncomfortably so—and his interactions with her daughters (Lily Colias, Kennedy Moyer) are equally awkward.

The supporting cast is filled with familiar names whose screen time ranges from fleeting to cameo-level. LaKeith Stanfield (Get Out) gets the most to do, playing Jeffrey’s confidant and adviser. Peter Dinklage (Game of Thrones) is wasted as the store manager, reduced to a stock “bully boss” role he performs well but far beneath his ability. Most puzzling are Ben Mendelsohn (Rogue One: A Star Wars Story), who plays a singing, dancing pastor, and Juno Temple (Ted Lasso), who appears briefly to help Jeffrey craft a disguise. Both are capable actors whose limited presence feels like a missed opportunity. It raises the question of whether they were cast merely for name recognition or if their scenes were cut in post-production. Uzo Aduba (Orange is the New Black) also appears briefly as the pastor’s spouse, leaving a stronger impression in a fraction of the time.

Cianfrance directs with a muted hand. There’s no flourish, no indulgent score, and little stylised framing—nothing that lingers once the credits roll. That restraint isn’t always a flaw; at times, it suits a story based on true events. But here it leaves long stretches feeling emotionally flat. The pacing drags early, then rushes to wrap things up, creating a film that feels oddly lopsided. For a story so steeped in nostalgia, it almost begs for more style—or at least a clearer point of view.

Beneath all the irony and nostalgia runs a current of desperation. Roofman isn’t just about confinement; it’s about the choices people make when every other door has closed. Jeffrey robs because he can’t imagine another path forward, hides because the world has stopped making space for him, and reaches for love because he’s terrified of being unseen. Cianfrance frames that desperation with empathy, but he never quite gives it the emotional gravity it deserves.

For all its surface irony, Roofman keeps circling back to one thing: the sadness of people trying to rewrite their lives in miniature. Jeffrey’s days in the toy store have a tenderness. He watches others live the normal life he’s forfeited, playing house through observation instead of participation. Cianfrance captures those small moments with empathy. He’s less interested in the crime than the psychology of a man desperate to feel useful again. In that way, the film becomes a portrait of loneliness as much as desperation.

In the end, Roofman is an interesting idea that doesn’t become an interesting film. Cianfrance’s understated direction keeps the story grounded but also strips it of energy, while Tatum’s earnest charm can only do so much with a script that never commits to its own tone. There are glimmers of insight—a clever metaphor here, a sharp image there—but they’re buried under uneven pacing and emotional detachment. It’s not a terrible movie, just an oddly hollow one: a film too strange to dismiss, yet too shallow to recommend.

USA | 2025 | 126 MINUTES | 2.39:1 | COLOUR | ENGLISH

director: Derek Cianfrance.

writers: Derek Cianfrance & Kirt Gunn.

starring: Channing Tatum, Kirsten Dunst, LaKeith Stanfield, Ben Mendelsohn, Peter Dinklage, Juno Temple & Uzo Aduba.