GENTLEMEN PREFER BLONDES (1953)

Two showgirls travel to Paris, pursued by a private detective hired by the suspicious father of one's fiancé, as well as a rich, enamoured old man and many other doting admirers.

Two showgirls travel to Paris, pursued by a private detective hired by the suspicious father of one's fiancé, as well as a rich, enamoured old man and many other doting admirers.

1953 was a banner year for Marilyn Monroe. She starred in three hits (Niagara, How to Marry a Millionaire, and Gentlemen Prefer Blondes), ascending from a supporting player to a bonafide star. Gentlemen and How to Marry a Millionaire were both in the Top 10 highest-grossing films of that year, earning the seventh and fourth spot, respectively.

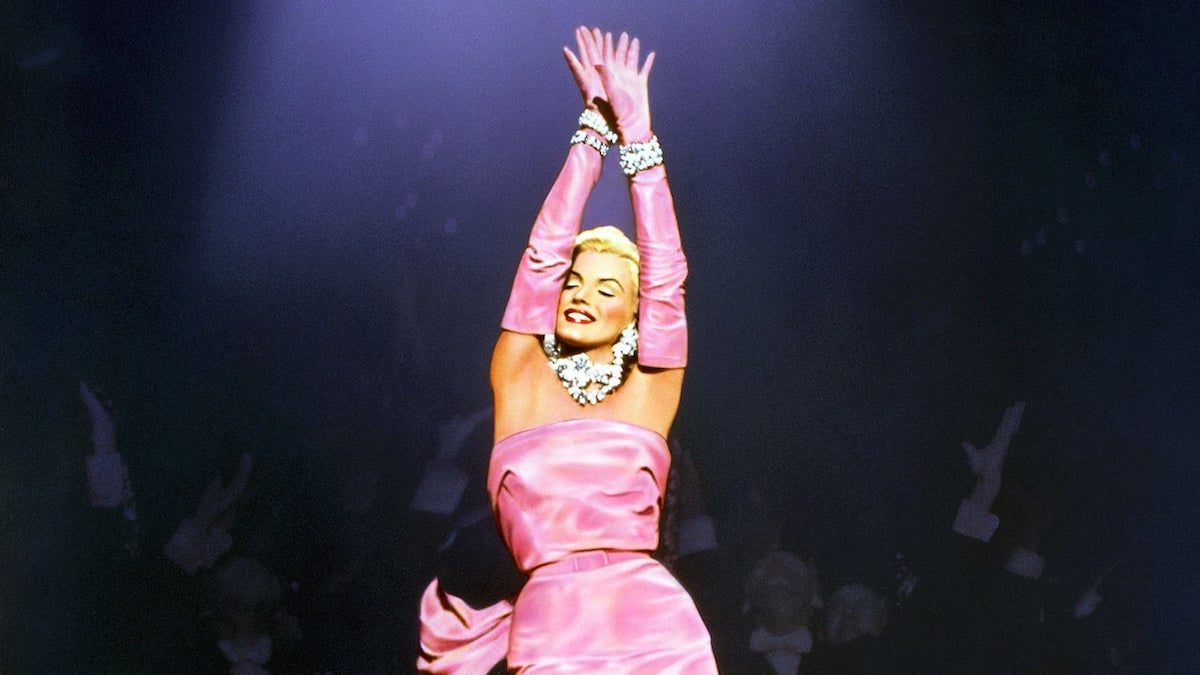

But of the three, none have become as intrinsically intertwined with her image and legacy as Gentlemen Prefer Blondes. The film turns 70 this year and, true to the philosophy of its most famous musical number, “Diamonds are a Girl’s Best Friend”, has lost none of its lustre. It’s actually better regarded now than it was upon release, as it reads as being ahead of its time for its incisive commentary on gender and class politics.

Decades before a term like “intersectionality” lept from the academic sphere into the cultural one, Gentlemen Prefer Blondes deftly portrayed the complications of mingling femininity and wealth and managed to do it in a sparkling and entertaining fashion. Many contemporary feminists, myself included, consider the film, and particularly Monroe’s performance, to be delightfully subversive. Considering the source material and its trajectory from literary phenomenon to Technicolor immortality, this comes as no surprise.

The story of Lorelei Lee begins with a 1925 novella of the same name by Anita Loos. An immediate success, Gentlemen Prefer Blondes made the leap to the stage in 1926, before being adapted into a 1928 silent film and finally a 1949 Broadway musical starring Carol Channing—which became the basis for the 1953 remake directed by Howard Hawks. The original story was set in the 1920s, but the time period and other plot points were updated for the ’53 version by screenwriter Charles Lederer. Ultimately, the backbone of the story remained the same: Lorelei Lee (Monroe) is a performer from a working-class background who wants to live well, marry rich, and isn’t ashamed of her desires.

Several of the original songs from the musical are included in the film, most famously the aforementioned “Diamonds Are a Girl’s Best Friend”, but some new songs were added. The changes resituated the story to the present day, making the two leading showgirls instead of flappers, then expanding the character of Dorothy (Jane Russell) to make the film more of a two-hander. Russell was a bigger name than Marilyn Monroe at the time, whose star was on the rise but the studio was betting on Russell being the box office draw. (Accordingly, Russell’s pay was enormously higher than Monroe’s.) But it’s Monroe’s character who anchors this film and her performance is what made it a classic.

The reason for this has to do with the content of the story itself. Lorelei and Dorothy, we learn in the iconic opening number, are from “the wrong side of the tracks” in Little Rock, Arkansas. Coming before the opening title sequence, the song efficiently establishes the two leading ladies and their goals. Rising from poverty, they desire love and financial security—but not necessarily in that order. As Monroe croons towards the end of the song, gazing at her lover the wealthy Mr Esmond, “I learned an awful lot in Little Rock, And here’s some advice I’d like to share: Find a gentleman who is shy or bold, Or short or tall, or young or old. As long as the guy’s a millionaire!”

Intended to be a send-up of Lorelei’s gold digger mentality, it also sets up the thornier themes at play in the film. Is it selfish to marry for money, as many other characters in the film tell Lorelei it is? Or rather, is it a concern she can’t afford to live without? Dorothy and Lorelei discuss this explicitly once aboard their ship to France, where Lorelei plans to marry her betrothed away from the influence of his overbearing father, and Dorothy accompanies her to chaperone. Lorelei is encouraging Dorothy to turn away from the attractive men in her orbit and instead find a wealthy one she can settle down with. Dorothy responds, “Honey, has it ever occurred to you that some people just don’t care about money?” to which Lorelei admonishes, “Please, don’t be silly. We’re talking serious.”

Though it was easier to laugh at such a brazenly materialistic character in 1953, today’s audiences are more likely to empathize with her plight and understand that what she covets goes deeper than diamonds. Social mobility remains elusive to those not born to privilege at the time, to women especially, and Lorelei’s comical quest for financial stability exposes how deeply the odds are stacked against her. She’s constantly being objectified and underestimated by men in the film (even by the men who made the film), who see her as a craven opportunist, but a more thoughtful reading of the film shows her to be exceedingly pragmatic.

In a world where she’s entirely on her own with little support (save her friend Dorothy), what choice does she have but to use her talents to obtain her goal? And how does that make her any different from a man? This point is made explicitly in one of the final scenes, where Lorelei confronts her future father-in-law about the nature of her desires. Monroe virtuosically plays every note in the scene, showing not just the keen intellect of her character, who for the entire film was belittled as a “dumb blonde”, but the deftness of her talent as an actor. In particular, this exchange stands out:

MR ESMOND: You admit that all you’re after is money? LORELEI: No I don’t. Aren’t you funny? Don’t you know that a man being rich is like a girl being pretty? You might not marry a girl just because she’s pretty, but by goodness doesn’t it help? And if you had a daughter, wouldn’t you rather she didn’t marry a poor man? MR ESMOND: But I’d--- LORELEI: You’d want her to have the most wonderful things in the world, and to be very happy. Well, why is it wrong for me to want those things?

The implications of her philosophy are undoubtedly complex, but they expose the very real choices we all must make, no matter what our attitudes towards love may be. It’s easy to say money shouldn’t matter in matters of the heart, but Lorelei knows better. We all need our basic needs to be met, we all deserve a life free of the pressures of poverty, but not all of us have access to such freedom. Her speech also highlights the hypocrisy of people like her future father-in-law, who’d presumably prefer his son to marry someone from their own elite circle instead of a showgirl from Little Rock. Modern day viewers resonate with the film’s frankness on matters of class and gender, and since most of the humour in the film derives itself from these conflicts that still persist, it holds up well today.

This isn’t to say the film entirely transcends its era. It’s obviously impossible to separate this film from the time in which it was made. Though there are progressive elements to the story and the main characters, it remains a product of a deeply misogynistic time. It’s clear from the filmmaking we’re not meant to view its heroines as fully formed agents of their own destiny, but as hapless nitwits who are easy on the eye. Jokes abound which reduce both Russell and Monroe’s value to their appearance. Furthermore, details about the making of the movie, in addition to the initial critical response upon release paint a more complicated picture of how this film has been understood, or misunderstood.

Hawks himself thought little of the project when making it, stating “The girls were unreal; the story was unreal; the sets, the whole premise of the thing was unreal. We were working with complete fantasy.” Hawks, a legendary director, made a name for himself directing other comedies such as Bringing Up Baby (1938) and His Girl Friday (1940), and dramas The Big Sleep (1946) and To Have and Have Not (1944). Though he’d developed a reputation for making films with strong female leads, even creating his own archetype of the “Hawksian woman” he didn’t consider Monroe to be in the same echelon as the likes of Katherine Hepburn or Lauren Bacall. In fact, he’s quoted as saying he found Monroe to be “so goodman dumb” after working with her on his previous film Monkey Business (1952) starring Cary Grant and Ginger Rogers. It’s hard to imagine his disdain was lost on her.

Hawks didn’t seem to have much patience for Monroe the actress, for Lorelei the character, or for the film itself. He also didn’t direct the film’s musical numbers and instead delegated that task to choreographer Jack Cole. But ultimately, his attitude towards the film and towards Monroe are reflective of the attitudes of the time, as early reviews of the film also showed. The New York Times review states that “the screenplay contrived by Mr Lederer is less the classic saga of two smart dames, which was originally played beneath this title, than it is a silly tale of two dumb dolls”, adding “there is not much class in this picture.” Variety wrote “a strong play to the sophisticated dialog and situations is given by Howard Hawks’ direction and he maintains the racy air that brings the musical off excellently at a pace that helps cloak the fact that it’s rather lightweight, but sexy, stuff. However, not much more is needed when patrons can look at Russell-Monroe lines as displayed in slick costumes and Technicolor.” As reflected in the reviews, more attention was paid to how the film’s leading ladies looked than to what they were saying (or rather, singing).

This view has persisted, even pervading the way we think about Marilyn Monroe as an icon. So much so that we’ve conflated her with her most famous character! But with the added benefit of time, and greater consideration to the talent she displayed throughout her career, it’s possible to see the film both for what it was and for what it is: a reflection of our changing attitudes on matters of gender and wealth. Of course, Monroe and Russell both stun in fabulous costumes by William Travilla, and the film is incredibly fun to watch, but its superficial delights should not overshadow the more interesting facets of the story. And in spite of his resentment, Hawks had the excellent instinct not to mess with the story too much. Though he may not have thought much of it at the time, he at least had the good sense to trust his leading ladies to make the story work, which they do with aplomb. Watching Gentlemen Prefer Blondes today, one can expect a more nuanced experience than may have been possible in 1953, to our benefit. The film gets richer with every viewing.

USA | 1953 | 91 MINUTES | 1.37:1 | COLOUR | ENGLISH • FRENCH

director: Howard Hawks.

writer: Charles Lederer (based on the stage play by Anita Loos & Joseph Fields, itself based on the novella by Anita Loos).

starring: Jane Russell, Marilyn Monroe, Charles Coburn, Elliott Reid, Tommy Noonan, George Winslow, Marcel Dalio & Taylor Holmes.