CINEMA PARADISO (1988)

A filmmaker recalls his childhood when falling in love with the pictures at the cinema of his home village and forms a deep friendship with the cinema's projectionist.

A filmmaker recalls his childhood when falling in love with the pictures at the cinema of his home village and forms a deep friendship with the cinema's projectionist.

From a young age, I saw something extraordinary and inspiring in the artistry of cinema. The images thrilled me but also illuminated something within me. Some people find similar solace in poetry, dance, or music… but , for me, my life revolves around film. It may sound pretentious to describe cinema as life, but Giuseppe Tornatore’s second feature film proved exactly that. Released in 1988, Cinema Paradiso / Nuovo Cinema Paradiso is a movie about the magic of cinema and reminds us why we fall in love with flickering images. Although it received only modest reviews in Italy, it found critical acclaim internationally and won ‘Best Foreign Language Film’ at the Academy Awards, revitalised Italy’s film production.

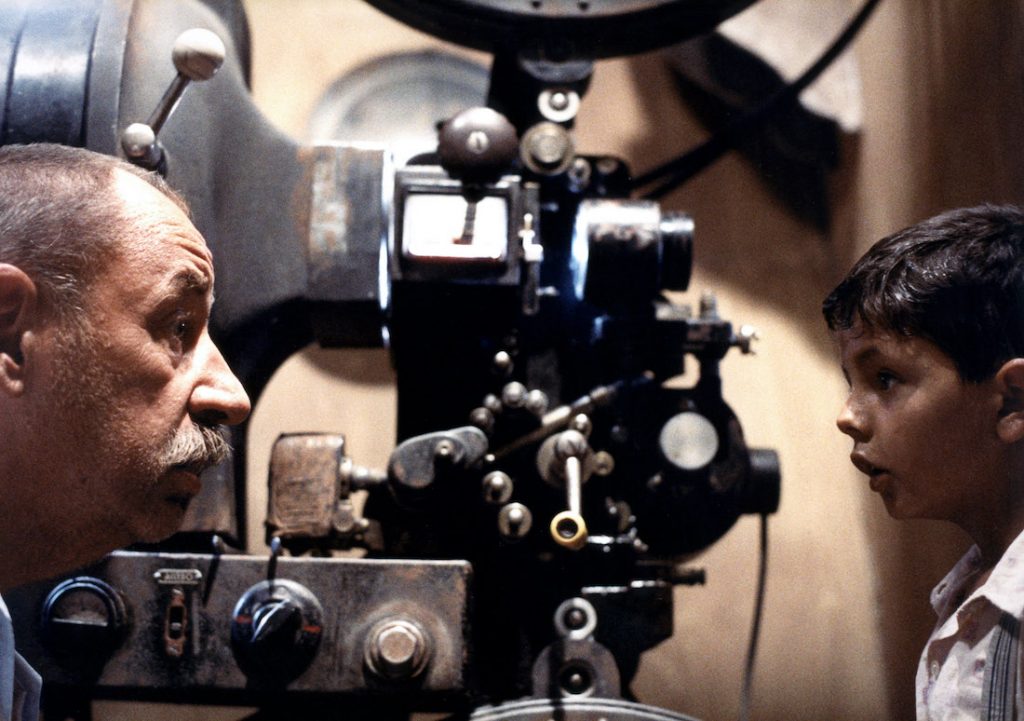

Set in a small Sicilian village during the 1940s and 1950s, Cinema Paradiso follows a boy called Salvatore (Salvatore Cascio) under the tutelage of the projectionist, Alfredo (Philippe Noiret). As a youngster, Salvatore aggravates Alfredo until he agrees to teach him the techniques required to control the cinema’s projector. But after a tragic turn of events the theatre burns down, leaving Alfredo without his eyesight. Later, when a lottery winner invests in a new cinema, Salvatore becomes the new projectionist and Alfredo continues to guide the now-teenage Salvatore (Marco Leonardi) as he falls in love with Elena (Agnes Nano). When she moves away, Alfredo encourages Salvatore to leave town and pursue his dreams, but he must never return. Salvatore keeps his promise for 30 years until he receives a phone call from his mother with tragic news. Now a successful filmmaker, an adult Salvatore (Jacques Perrin) returns to his hometown to confront everything he left behind.

In the three roles of Salvatore, the highlight is easily Salvatore Cascio (Everybody’s Fine) as our young protagonist. His winning smile lights up the room, whereas his carefree innocence and mischievous personality make him a joy to watch. Every minute he’s on-screen, he captures the essence of youth and his passion for films is easily relatable. Watching the wonder of cinema through a child’s eyes instantly provided me with a sense of warm nostalgia. His mesmerising expression reminded me of my first cinema experiences.

Marco Leonardi (Once Upon a Time in Mexico) as the teenage Salvatore picks up perfectly where Cascio left off, with a charming performance that’s more complex as a young man trying to figure out where to go in life. He’s engaging and handsome, showing just the correct amount of angst as a young man falling in love for the first time. Although only briefly featured, Jacques Perrin (Girl with a Suitcase) is also excellent as the adult Salvatore. His face contains a similar innocence as his child counterpart and his emotional closing scene is truly outstanding. Collectively, it’s believable that all three actors are the same person.

The venerable Philippe Noiret (Topaz) as Alfredo delivers the best performance and remains one of the greatest fictional mentors in film history. Noiret plays Alfredo wonderfully, with a perfect mix of humour, wisdom, and sentimentality. With his droopy long face, thick moustache and big eyes, the image of Alfredo is difficult to forget. The French actor manages to juggle various character aspects of Alfredo with ease. While mainly reciting film quotes, he’s responsible for several of the lighter moments, particularly during a scene where he offers Salvatore some advice saying “the bigger the man, the deeper the footprint. And if he loves, he suffers, knowing it’s a dead-end street”. As Salvatore replies “that’s nice, what you said. But sad”, Alfredo responds “I didn’t say it. It was John Wayne in The Shepard of the Hills”. However, he’s dramatic when the plot requires (“life isn’t like in the movies. Life… is much harder”). Noiret breathes the correct amount of heart into his character and everything he does is because he genuinely cares about Salvatore.

Writer-director Giuseppe Tornatore masterfully constructs a period-piece that’s undeniably one of the greatest love letters to the medium. More so than La La Land (2016) and Once Upon a Time… in Hollywood (2019), Cinema Paradiso serves as a celebration of Hollywood’s Golden Age. Throughout there are dozens of clips that evoke the heritage of cinema from Jean Renoir’s Lower Depths (1936) to Frank Capra’s It’s A Wonderful Life (1946). Simultaneously, the director demonstrates the ways in which film can compel, challenge, and unify individuals from a variety of backgrounds.

Although the townsfolk remain divided over war-time alliances, class division, and personal grudges, once they sit down in the darkened room, everything’s forgotten until the end credits roll. An argument could be made that the director’s formulaic and romanticised perspective makes a less substantial film. However, it can easily be contested that Cinema Paradiso epitomises what film does best. The cinema is a place where people can escape from the mundane realities of life and where people can feel happy. Tornatore proves that for some, the cinema is more than a location of passive entertainment, it’s a place of enchantment.

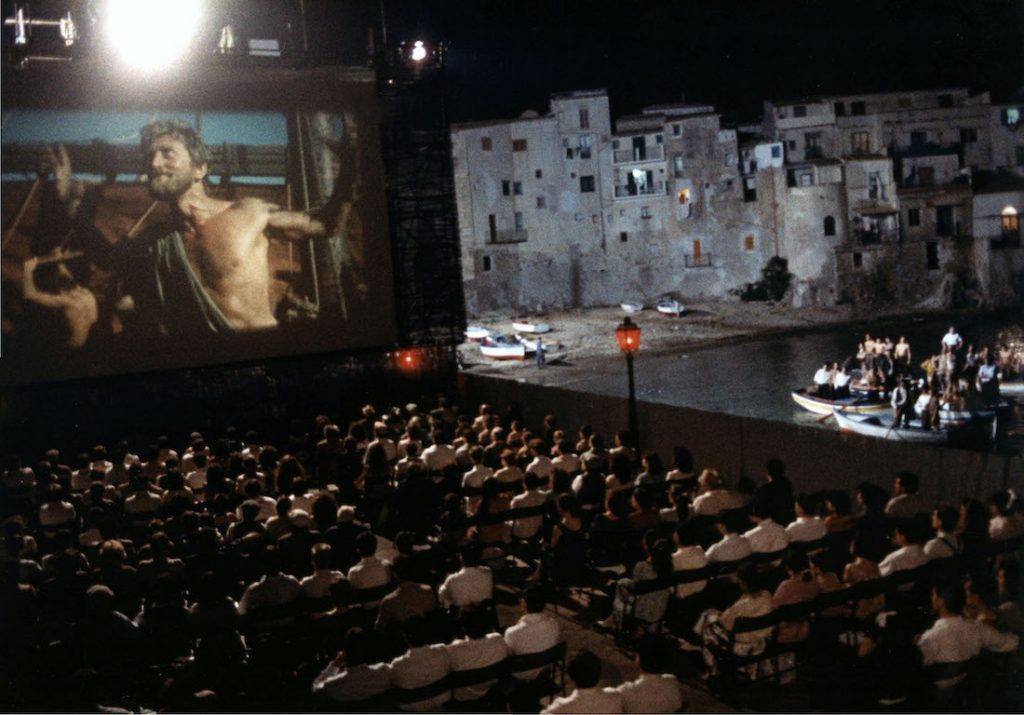

Similar to Federico Fellini’s 8 1/2 (1963), each sequence within Cinema Paradiso emphasises the magical quality of cinema. Tornatore crafts a film that not only has mass appeal for film lovers but also for filmmakers as he delivers one stunning visual after another. One personal favourite is a most inspiring scene that’s so simple yet totally captures the allurement of film. During an evening when the cinema’s reached capacity, the patrons are gathering outside waiting to enter. As they’re rejected by the owner, they call up to Alfredo to help them. The projectionist smiles knowingly and asks Salvatore if they should satisfy the crowd’s appetite. As the young boy agrees enthusiastically, Alfredo adjusts the mirror on the projector and an image appears on the wall. Salvatore’s eyes widen in excitement and wonder, as the mirror is moved further and the image moves along the wall. It crosses the room before appearing full-sized on the wall of the building across the town square. The sequence is beautifully constructed and hearing the villagers rejoice creates goosebumps upon each viewing.

Seeing the town of Giancaldo watching films on the big screen is both charming and hysterical. Whether it’s the John Wayne western Stagecoach (1939) or the hilarious Charlie Chaplin comedy The Knockout (1914), their reactions provide plenty of humour and pathos. Similar to Fellini’s Amarcord (1973), Tornatore creates a whole series of background characters that are so distinctive and endearing. There’s a couple who meet and fall in love in the cinema due to their shared enjoyment of horror films. Along with a wealthy snob spits on the ‘cheap seats’ from the balcony, ending up with an ice cream sandwich thrown in his face. However, the highlight is the local priest Father Adelfo (Salvatore Cascio), who approves each film before public viewing and censors scenes of intimacy he deems immoral. As he loudly rings his bell when he objects, Alfredo marks the scene and cuts the reel. This leads to a great moment of the village erupting in anger in the theatre. One man exclaims “I’ve been going to the movies for twenty years and I never saw a kiss”. Tornatore captures so much life within the cinema that every shot is filled with someone that could have an entire story.

The heart and soul of Cinema Paradiso is the sentimental relationship between Salvatore and Alfredo. The first half of the film, as the narrative follows their blossoming relationship, is the strongest portion. As a young altar boy, Salvatore has little interest in anything apart from the film and, luckily for him, there’s a cinema in his small village. The young cinephile spends most of his time around the projection booth where Alfredo is screening films to the town. Although his mischievous antics infuriate the old man, they are brought together by their mutual fascination for film. The gruff projectionist grudgingly nurtures and guides Salvatore, allowing him to work in the projection booth as his protege. Alfredo soon takes pride as he watches the young boy master the intricate craft of running a projector, splicing film, and changing reels. As the child finds a paternal figure in Alfredo, the elderly man finds solace in Salvatore. Both Noiret and Cascio create a defined and organic relationship between the two characters that is incredibly heartwarming.

Once Salvatore becomes a teen, Cinema Paradiso changes from being a nostalgic celebration of cinema to a more traditional coming-of-age drama. The protagonist’s love of film evolves into a standard love story as he meets Elena. Her father, a wealthy banker, frowns upon a peasant boy courting his daughter of privilege. During a scene, Alfredo offers Salvatore some advice, sharing a story about a knight. The knight sought after the heart of a beautiful lady, who promised to marry him if he waited under her balcony for 100 nights. The knight waited for 99 nights, before finally leaving with his heartbroken. As Salvatore does the same with Elena, she eventually falls in love with him. At the height of their romance, Salvatore is required to serve his compulsory military service and heartbroken when his letters to Elena are undelivered. Returning to the village after completing his service, he discovers his girlfriend’s family have settled elsewhere. It’s here when Alfredo pushes him to take the step towards his destiny and leave for Rome. In an incredibly bittersweet moment, he says “I don’t want to hear you talk anymore. I want to hear others talk about you”.

Originally Cinema Paradiso had a runtime of 155-minutes. However, due to a poor box office performance, Miramax removed over 30-minutes for its international release. The Theatrical Cut garnered numerous awards including the Oscar for ‘Best Foreign Picture’. Unlike Ridley Scott’s Blade Runner (1982) and James Cameron’s Aliens (1986), Cinema Paradiso is one of those rare films that benefitted from studio interference. In 2002, the Director’s Cut was released, running a lengthier 174-minutes. The additional 50-minutes examined Salvatore’s relationship in more depth. Although one can argue the romance is the weakest element, the love story remains genuine and sweet. Tornatore creates an incredibly romantic scene as Salvatore is working as a projectionist, throughout the summer. During one night, he lies on his back wishing for the summer to end so he can return to Elena. He muses “In a film, it’d already be over. Cut, and there’s a storm”. Suddenly, there is a clap of thunder and rain pours down. A relieved Salvatore remains on the ground delighted that his wish came true. As a broad smile rises on his face, suddenly Elena appears above him and kisses him.

Although it’s incredibly charming watching their romance blossom, it severely disrupts the pacing of the second half. While several relatively inconsequential scenes have been added into the Director’s Cut, such as Salvatore losing his virginity to a prostitute. The majority of the additional footage arrives during the third act, giving closure to Salvatore and Elena’s story. The extended version provides additional depth and poignancy to their relationship. However, an argument can be made that it removes some of the mystery posed by the Theatrical Cut. We see a middle-aged Salvatore return to his hometown for the first time since he left for Rome, along with the destruction of the theatre. He also reunites with an adult Elena and discovers how easily his life might have turned out differently. It’s a personal preference, but the cut version handles the friendship between Salvatore and Alfredo so well, that the love story overthrows the narrative. Nonetheless, without disavowing the Director’s Cut, I still believe it’s still worth viewing.

Lensed by the Italian cinematographer Blasco Giurato (A Pure Formality), Cinema Paradiso is a visual feast. The sun-kissed aesthetic captures the director’s hometown with great authenticity and brings a wonderful look to the film. Each composition romanticises the beautifully alluring vistas of Sicily and the exterior shots of the theatre equally look as gorgeous. It’s enhanced by the seamless editing of Mario Morra (The Battle of Algiers), who was nominated for a BAFTA for his work. A highlight is the sequence of Salvatore changing from a child to a teenager. After a tragic incident, a blind Alfredo returns to the Cinema Paradiso to visit the young boy. As he reaches out to touch his face, the old man says “now I’ve lost my sight, I see more. I see everything I didn’t see before…” As the camera cuts back to Salvatore, we notice he’s become a handsome young man. It’s an incredible moment and a breathtaking way to progress the narrative.

The BAFTA-winning score by the iconic Italian composer Ennio Morricone is utterly spellbinding. His upbeat and whimsical harmony is different from the legendary work he created for Sergio Leone’s The Good, The Bad, and The Ugly (1966). The gentle and elegant piano melodies complement the sentimental tone that Tornatore aims for. The main theme “Cinema Paradiso” is beautifully bittersweet, evoking a warm feeling of nostalgia. Whereas “Childhood And Manhood” and “Love Theme” highlights Salvatore’s journey through adolescence as he falls in love for the first time, ultimately facing the world outside of the theatre. Whereas the melancholy strings perfectly reflect the character’s emotions, while creating a sense that we’re watching the director’s personal history. It’s a travesty that Morricone’s work was overlooked for an Academy Award nomination and lost to Disney’s The Little Mermaid (1989). Nevertheless, it remains a personal favourite and one of the composer’s most iconic pieces of work.

Cinema Paradiso isn’t just a coming-of-age drama that examines friendship and romance… it’s a celebration of the silver screen at its finest. It highlights the sensation all cinephiles experience when they sit in a darkened room in front of a larger-than-life screen. Tornatore captures that moment in time when the images and sound wash over you and transport you to a magical place. The final scene, which I’ve alluded to this entire review, includes one of the most moving montages I’ve ever seen on celluloid. Without delving into spoilers, it’s one of the most heartfelt moments in cinema that transcends the language barrier. Cinema Paradiso simultaneously encourages laughter and tears but most importantly will make you appreciate the love of those surrounding you.

If you enjoyed reading this review, please support my writing and buy me a coffee.

ITALY | 1988 | 174 MINUTES | 1:66:1 | COLOUR | ITALIAN

As expected, Arrow Academy has done a wonderful job delivering a 4K Ultra HD restoration of the Theatrical Cut. Sourced from the original 35mm negatives, Cinema Paradiso is presented in its original aspect ratio of 1:66:1 in 2160p. Additionally, the Director’s Cut has also received an impressive 2K restoration with a 1080p transfer supervised by director Giuseppe Tornatore. The result is an incredibly crisp and detailed image that is a significant improvement compared to Arrow’s previous 2017 release. The real showcase are the sun-kissed panoramic shots of Giancaldo, the rich naturalistic colour is a feast for the eyes. The daylight footage boasts a tremendous depth with each background building remaining incredibly detailed. Additionally, background details such as Gone with the Wind (1939) and Casablanca (1942) posters hanging throughout the theatre appear sharp and well defined.

The film texture contains a noticeable but not overwhelming amount of grain, capturing the highly desirable filmic appearance the director aspired to. Contrast levels remain stable throughout with natural skin tones. Arrow’s previous release contained heavy noise and blue tint during the interior scenes. Thankfully the black levels and shadow definition has been corrected offering a sharper contrast. Unfortunately, the Director’s Cut not presented in 4K, but the restoration still looks incredibly beautiful. There’s some noticeable evidence of debris, scratches, and dirt being removed during the additional footage. However, it doesn’t distract from the overall image. It’s clear Arrow has taken great care to ensure the film’s original texture, grain structure, and soundtrack remain unaffected.

There are two audio options for each version of Cinema Paradiso. The Theatrical Cut features Italian DTS-HD 5.1 and LPCM 2.0 Mono, whereas the Director’s Cut features Italian DTS-HD 5.1 and LPCM 2.0 Stereo. Unlike Arrow’s previous release, the English subtitles for the main feature are optional. Admittedly, there’s no discernible difference between the two audio tracks on either option. Dialogue is consistently clear and stable with no undertones of distortion such as cracks of hiss. Background village activity is evenly balanced throughout the sound field, whereas the raucous scenes surround rear channels creating an ambiance. Arrow’s 5.1. track handles Ennio Morricone’s superb score exceptionally well. It’s crisp, spacious, and benefits a great deal from the surround presentation. However, don’t expect to hear a dramatic improvement in overall dynamic intensity when switching between LPCM 2.0 and DTS-HD 5.1.

writer & director: Giuseppe Tornatore.

starring: Philippe Noiret, Salvatore Cascio, Marco Leonardi, Jacques Perrin, Agnes Nano, Brigitte Fossey, Antonella Attili, Pupella Maggio, Enzo Cannavale, Isa Danieli, Leopoldo Trieste, Nino Terzo, Giovanni Giancono.