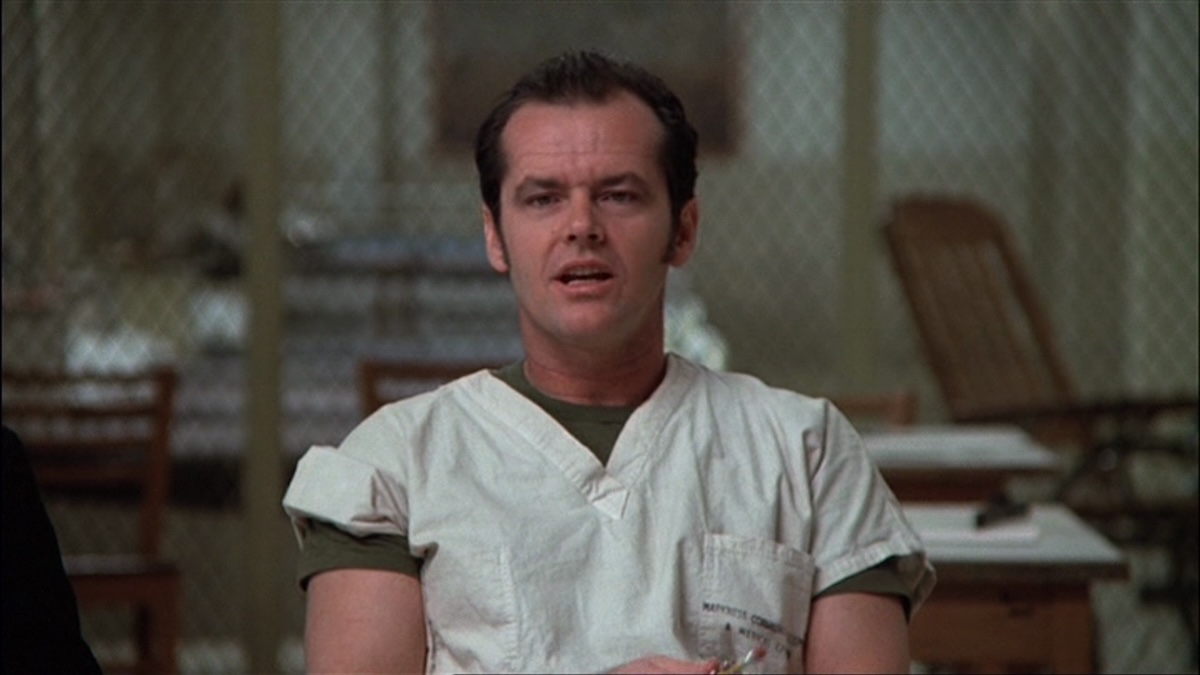

ONE FLEW OVER THE CUCKOO’S NEST (1975)

A convict is sent to a psychiatric hospital for evaluation and encourages his docile companions to take control of their lives and defy the tyrannical head nurse.

A convict is sent to a psychiatric hospital for evaluation and encourages his docile companions to take control of their lives and defy the tyrannical head nurse.

One Flew Over the Cuckoo’s Nest is a film of expanding and of restricting. We start with a vista just before first light, the sun creeping up on the snow-capped Oregon mountains, a dull snowy lake brooding in the foreground. A car snakes through the dark. The dream is washed away. The smell of ice and snow and trees suffocated now by the chemical compounds of pus-like yellowy-white paint. The halls stretch in quiet echoes, broken up occasionally by barred windows, as if under siege from the elements brewing outside, blind to those blooming within.

This psychiatric hospital (which remains unnamed in the film) will come to represent the antithesis of personal freedom, but did any of these people have it in the first place? Do any of us? The patients shuffle along in white uniforms, mostly pacified, some jittering with nervous energy. One man is strapped to a bed. The rest take their medicine. The janitors, all African-American, mop the floors in identical white shirts and bow-ties, forcing out ‘good morning Mrs Ratched’ almost in unison.

When Randle Patrick McMurphy (Jack Nicholson) arrives, he’s already in handcuffs, retrieved by guards from the backseat of the car we’d seen crawling along in the dark earlier—perhaps he managed to snatch a final view of nature through frosted windows, or perhaps it was all too dark to make anything out. To someone like Randle, it probably all looks the same anyway. He isn’t one to think of anything larger than his own immediate needs. And at the moment, his needs are shackled.

McMurphy is a convict with a long rap sheet. He has a history of assaults and, most recently, he was arrested for the statutory rape of a 15-year-old girl. Now, sitting before the superintendent, Dr Spivey (Dean Brooks, who was the real-life superintendent of the psychiatric hospital in which Cuckoo’s Nest was filmed—this was his only acting credit), we get our first sense of who McMurphy is…or at least, who he wants us to believe he is.

Nicholson is in enthralling form here; his devilish eyebrows never quite so insistent, his grin flashing between moments of fitful squirming; he’s like a kid in the principal’s office, desperate to get back out on the playground. When he’s amongst his fellow patients, he’s watchful, surveilling their behaviours and dynamics with studious remove. But when he’s amongst the doctors and nurses, the showman in McMurphy is teased out.

He sucks on a cigarette with the laconic cool of someone trying to look like they’re unaware they’re being photographed. He throws out phrases as if he’s hoping to be quoted. “I fight and fuck too much”, he grins as an answer to why he believes he’s there. Spivey has a different view of things. “You’re resentful in your attitude towards work. You’re lazy”. He thinks it’s all an act to avoid prison labour.

The film, based on Ken Kesey’s novel of the same name, is set in 1963. Yet, whether it’s 1963, 1975, or 2025, the attitude remains unchanged; you’re a reprobate if you don’t care about contributing to a system that only serves to uphold an oppressive status quo. Kesey had worked the night shift at a mental health facility in the 1950s, and what he saw during his time there influenced him to start work on the novel.

Kesey’s caustic material is well served by Miloš Forman, whose warmth and humanism never sands down Kesey’s edges. Rather, Forman’s focus on people, on actors, allows for a level of connection between us and these characters, whether we like their company or not. McMurphy can be vile—we aren’t asked to ignore the despicable act with which he has been charged.

But Forman’s film, with a screenplay adapted by Lawrence Hauben and Bo Goldman, isn’t interested in heroism or even anti-heroism; instead, these characters exist on a more life-like scale, fucked up in ways that are difficult to look at—even the film’s quasi-villain, Nurse Ratched (Louise Fletcher), is more complicated than the film’s thorny legacy allows for.

Nurse Ratched is a name one might hear alongside Norman Bates or Michael Myers these days—certainly not helped by the fact that Ryan Murphy’s soulless empire of cultural cannibalism disguised as bingeable TV produced a psycho-thriller prequel series titled Ratched (2020).

But this could only happen if there wasn’t already a just-beneath-the-surface wellspring of misogyny in the culture’s response to Nurse Ratched in the first place. Her name itself has become a stand-in for loathsome bureaucratic cruelty—she even came in at number five on the American Film Institute’s list of the big screen’s greatest movie villains, beating out the likes of Ralph Fiennes’ murderous Nazi Amon Göth from Schindler’s List (1993) and Dennis Hopper’s sadistic rapist Frank Booth in Blue Velvet (1986). She ranked higher than the Great White shark in Jaws (1975), the xenomorph from Alien (1979), and child murderer Freddy Krueger from the Nightmare on Elm Street series. One spot above her on the list is Star Wars villain Darth Vader.

Nurse Ratched wouldn’t appear on this list if Louise Fletcher’s performance wasn’t so brilliantly calibrated. Ratched wears a fixed expression when talking to the patients, an almost smirk, as if to undercut McMurphy’s mad grin—a sort of condescending interpretation of the Mona Lisa Smile, her lips creeping ever so slightly at the corners, her eyes warm but remote. She speaks calmly, a therapeutic cadence that you might hear these days on some digital assistance device.

You can see some of the reasoning behind her reputation as the most evil person in film history. Within Cuckoo’s Nest, she’s the blank face of authority; the form you didn’t fill in on time; the medication you’re prescribed without knowing what’s in it; the petty rules that can make life feel so incredibly stifling. Her abuses don’t stretch to the physical, as far as we see, but the emotional torment of these patients is more than enough.

And she’s a woman against 18 men. The nascent, angry man energy of the ward is whipped up into a frenzy by McMurphy’s slacker-machismo; if he’s the walking embodiment of fing and fighting, does that make Ratched the thing that must be fought, and fed? Ratched, under Forman, is like his Salieri in Amadeus; a representation of larger shadowy villainy, but with a withering, bitter humanity underpinning it all. Could she possibly be happy?

During interactions between Ratched and her colleagues in meeting rooms, she appears genuine, troubled by the jeopardy that her patients might find themselves in with the appearance of this outside agitator. Forman does not depict her as a sadist, but as someone attempting to tranquilise the inherent nature of the ‘mentally ill’—an act which, in itself, is perhaps an even greater evil.

McMurphy tries to run the place like a jail. He introduces ‘Chief’, a six-foot-something deaf-mute Native American, to modern American culture; he gives him Juicy Fruit bubble gum and teaches him how to dunk a basketball. He rallies the guys together to try and convince the staff to let them watch the first game of the World Series. He gathers them around to play poker with cards with naked women printed on them, betting with cigarettes. Eventually, he even breaks them out for an unsanctioned fishing trip, complete with booze and women.

McMurphy is the impulsive, wild spirit of the 1960s, adrift in the post-war years, not looking for a revolution so much as a few hours of fun. If the staff at the institute represent a fascist leaning America seeking to medicate and placate individualism, then McMurphy is pure id, ‘dangerous’, but ‘not crazy’.

When One Flew Over the Cuckoo’s Nest was written, America had only just witnessed the McCarthy witch hunts, not to mention the fallout experienced as it dawned on the people that their government did not have their best interests at heart—particularly if you held a belief or friendship at odds with the prevailing systems.

If a government could turn friends against friends, family against family, if it could legally dismantle a person’s very way of thinking and being, before a court and before the world, then it had authority to do basically anything else it deemed necessary. And locked away in a prison cell, or on a ship back to a mother country, or within the walls of a psychiatric hospital, we find a microcosm of a world at large, tearing itself to pieces to try and root out the infidels, a quest for dominance and control never ending.

McMurphy fights against uniformity, but we sense a slow immersion with his surroundings. His trademark denim shirt is soon layered underneath the boxy white shirts of the ward, and when he’s amongst his fellow patients we see a back-and-forth ease, a man letting his guard down. He talks about how desperate he is to leave, but he seems more like a class clown who’s been held back several years, happier than he’d admit being the big fish in a small pond, casually dazzling his hangers-on with tales of adventure from the outside.

McMurphy may be under the rules and watchful eye of the institute, but he’ll assert his dominance where he can, installing himself as the ersatz leader of the hospital. And it’s amongst these men that Forman’s film is at its warmest, its most touching. Will Sampson’s smile, as he skips along the basketball court, is enough to make your entire year, and Brad Dourif’s first film role as the young, stuttering Billy Bibbit, is entirely winning, a performance so sweet-natured and vulnerable it can be painful to witness.

Forman is careful to dial his actors’ performances to something earth-bound and fundamentally human. William Redfield is another standout as Dale Harding, a middle aged neurotic clad in a dressing gown with a cigarette permanently wedged between his fingers. He talks about his wife’s supposed infidelities, seemingly in the throes of a breakdown. But he’s erudite, clear-eyed—his friends mock him for his choice of language, and the session descends into arguing.

Even when these men are amusing (and they are—Danny DeVito and Christopher Lloyd deliver a two-hander of hysterical physical performances), they are not punchlines, nor are they clichés waiting to give profound insights into the workings of an unconventional mind. Some of them are there voluntarily, some are aware of their conditions, others not. Each is struggling in a manner that neither McMurphy nor Nurse Ratched can understand. Nobody is meeting these people on their level.

There was, and remains still, a true misunderstanding of mental health in our culture, and how it affects a person beyond the happy-sad, black-and-white dichotomy. McMurphy is unprepared for how bad it can get. At first he’s a method actor, ready to inhabit the role at whatever cost. Then he’s something of a folk hero, having blown in across the cold wilderness, arriving here to liberate the minds and hearts of the men. Nothing is ever that simple.

These men are not here to avoid jail time; those that are there voluntarily remain because they are frightened of a world that is inhospitable to them, because there’s nobody else on the outside who will understand it like this strange family that has grown on the inside. McMurphy can’t fathom that anyone would be there by choice, and is horrified to learn that the hospital can keep him there as long as they feel it necessary.

They medicate McMurphy and give him shock treatment. We see wards where men have been given lobotomies or are else too drugged to see straight. Frederick Wiseman’s seminal documentary Titicut Follies (1967) comes to mind, in which images of men in gowns drift by like ghosts, where sparse rooms offer nothing but long periods of waiting. One Flew Over the Cuckoo’s Nest isn’t disturbed by these people, but by their treatment from a society that wants nothing to do with them, and from institutions that benefit from their captivity.

But let’s return finally to that first scene. The first thing that we hear is the wind howling, harsh and frigid. The electricity in the air is tangible by the time an eagle screeches from somewhere off-screen—and is joined by the ominous quivering of composer Jack Nitzsche’s musical saw. The sound is played by taking an ordinary handsaw and using a bow to play it like a violin. It sounds like the future and the past at once; ancient like a long extinct creature, yet approaching the electronic cry of a theremin. The jagged teeth of the saw give a rugged, dangerous beauty; soul stolen from metal. Woodwind pipes, tambourines, sleigh bells, a gently plucked guitar, loping like a cowboy theme met with something Native and ghostly.

It’s pure nature, a meeting of disparate human cultures, whereupon a common ground is built, an ineffable human persistence that’s quite apart from any one person, or any one action. It cannot be medicated, untaught, or locked away, only listened to. We eventually learn to listen to Chief. “Mac, I feel as big as a damn mountain”, he confides in McMurphy, recalling again that beautiful opening vista.

The music swelling, humanity once more rejoined with the natural world, both internal and external, I recall the song “After the Gold Rush” from Jack Nitzsche’s close collaborator, Neil Young. The track, which brings up images of a natural world in peril, of a sequestered people searching for a way forward, repeats the refrain “look at mother nature on the run in the 1970s”. This is what we find in Cuckoo’s Nest: a withdrawing to supposed safety, to padded rooms, to tranquil, inoffensive music, far away from the dangers and wilds of the world, in a last gambit of self-preservation before the sun finally rises over the mountains and all is clear again.

USA | 1975 | 135 MINUTES | 1.85:1 | COLOUR | LANGUAGE

This release of One Flew Over the Cuckoo’s Nest is presented in 4K Ultra HD 2160p with HDR, taken from a 2025 restoration by The Academy Film Archive, which used the original 35mm picture negatives as the source, and the 2001 5.1 theatrical mix, which was previously approved by Miloš Forman. This is a beautiful film that now looks the best it ever has. The film’s interiors are as painterly as anything in Forman’s later hit, Amadeus (1984), with colours vibrant and bold throughout—the whites and blues of the costuming are particularly arresting.

The film’s natural grain is present, and the image is crisp and sharp besides one or two brief moments of a slightly softer image. This is preferable to over-corrected, far too sharp images, however. The soundtrack is hefty when music plays and when chaos erupts (the film’s iconic final moments sound especially impactful), but this is largely a dialogue heavy film, which all sounds clear, crisp and well mixed.

director: Miloš Forman.

writers: Lawrence Hauben & Bo Goldman (based on the novel by Ken Kesey).

starring: Jack Nicholson, Louise Fletcher, William Redfield, Will Sampson, Brad Dourif, Sydney Lassick, Christopher Lloyd, Danny DeVito, Dean Brooks, William Duell, Vincent Schiavelli & Michael Berryman.