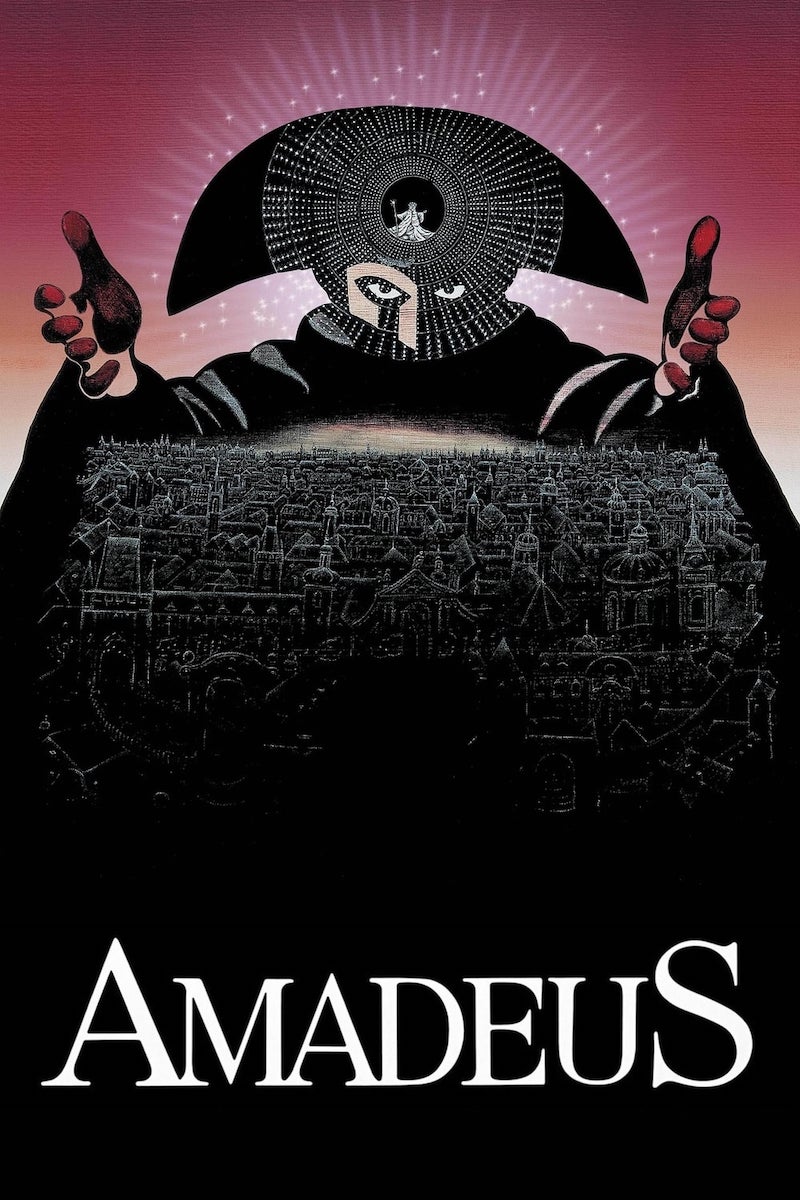

AMADEUS (1984)

The life, success and troubles of Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart, as told by Antonio Salieri, the contemporaneous composer who was insanely jealous of Mozart's talent and claimed to have murdered him.

The life, success and troubles of Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart, as told by Antonio Salieri, the contemporaneous composer who was insanely jealous of Mozart's talent and claimed to have murdered him.

You’re definitely Mozart, mate, and I’m definitely Salieri.

That’s the highest compliment pop star Ed Sheeran can pay to a fellow songwriter in Danny Boyle’s Yesterday (2019), but it’s doubtful Sheeran would have an opinion on the relative merits of two 18th-century composers if it weren’t for Miloš Forman’s 1984 drama Amadeus.

This fictional saga of Antonio Salieri’s (F. Murray Abraham) murderous resentment is surely the best-known movie about classical music. A difficult art to represent onscreen because the works are so comparatively long (you can show a four-minute rock song in its entirety, but hardly a 40-minute symphony). It’s also one of the most successful in both commercial and critical terms, although Roman Polanski’s The Pianist (2002) delivered even better box-office returns and runs a close second to Amadeus for winning major awards.

Certainly, Amadeus wowed the critics in ’84. Few were worried by the over-the-top performances or the feeling that there’s always a proscenium arch just out of sight. It won eight Academy Awards, including ‘Best Picture’, ‘Best Director’, and ‘Best Adapted Screenplay’, and also did well at the Golden Globes. Financially, it was the highest-grossing “serious” movie of that year, although inevitably it couldn’t compete on raw numbers with mainstream fare like Beverly Hills Cop, Ghostbusters, Indiana Jones and the Temple of Doom, and Gremlins.

However, Amadeus has had a profound influence that goes well beyond the cinema, largely because—despite only being loosely based on reality—it has often been taken as an accurate account of Mozart’s life, character, and death. Indeed, it’s remembered not so much as a film as for the historical figures it depicts or misrepresents: the foul-mouthed, infantile, but exquisitely talented Wolfgang “Wolfie” Amadeus Mozart (Tom Hulce) now provides the popular image of Mozart, while poor old Salieri epitomises the unimaginative, conservative artistic establishment trying to suppress true creativity.

Even if many of Amadeus’s departures from strict historical accuracy are minor, this dichotomy between the two main characters is a principal reason that it’s often loathed across the classical music scene. The real Mozart was certainly not above a dirty joke or ten, but equally (as his letters show) he was capable of thoughtfulness and spirituality. Amadeus, however, paints him as a kind of idiot savant, incapable of reflection or judgement but blessed with an incomprehensible genius for producing sublime music from out of nowhere. Everything about the way he’s presented (like he messiness of his home versus the economy and elegance of his music) reinforces this duality.

Equally, though Salieri was no Mozart, he was a more than competent composer—not a talentless plodder as the movie depicts. Ironically although he’d been all but forgotten, except by a few musicologists, his own work has enjoyed a revival post-Amadeus. And there’s no evidence at all that Salieri resented Mozart, which is the foundational idea of this film and the original play by Peter Shaffer, let alone plotted to kill him!

More broadly—and to be fair this criticism can be aimed at many movies about composers, writers, or artists—there’s an annoyance that Amadeus perpetuates the myth of art deriving directly from life. It is simplistic, critics say, to imply that Mozart based the character of the fearsome Commendatore in Don Giovanni so overtly on his father, or to suggest that the nagging shrieks of Mozart’s mother-in-law were translated straight into the shrill Queen of the Night aria from The Magic Flute. Real creation is a more complex process.

There’s some merit to these complaints, but Forman’s Amadeus itself is often misunderstood too. Most notably, when Salieri swears lifelong enmity, depressed by his own inability to produce work like Mozart’s despite his dedication to music, his real foe is not the younger man… but God. Salieri believes he’s made a bargain with the deity to gain fame as a composer in return for leading a devout life. So when bawdy, un-pious Mozart seemingly finds it so easy to produce music so much more glorious than Salieri’s, it seems like God is reneging on their deal. However, though this is made very clear both in the movie and in the rather different stage play, there’s still a widespread idea that Salieri’s hatred is directed at Mozart himself.

In fact, the relationship between Salieri and what he describes as the “dirty-minded creature” Mozart is one of the more interesting and understated touches in a movie that generally paints big, broad pictures rather than finessing the details. Salieri may envy Mozart but he cannot help respecting him too, and (not being a malicious man, at least until twisted by his disappointment) he also cannot help liking Mozart a little, or feeling sorry for him in his final illness.

This comes through in two important scenes. First, when the pair discuss Mozart’s opera The Marriage of Figaro we see that, despite Salieri’s duplicitousness, he cannot restrain his genuine enthusiasm for what Mozart’s composed. Then, later, as the dying Mozart dictates part of his Requiem to Salieri from his deathbed, we perceive an almost intimate connection between them.

On one level, this scene toward the end of the film might represent the triumph of Salieri’s devious plan—having commissioned the Requiem from Mozart in disguise, he plans to pass it off as his own once the younger man is dead. Yet however much he might want to be bad, he can’t entirely overcome his innate decency and recognition of Mozart’s genius. (The whole Salieri-disguise-Requiem scheme is an invention of Shaffer’s with no historical evidence to support it; the identity of the actual commissioner, a minor nobleman called von Walsegg, is known.)

Amadeus does not always, then, thematically say exactly what it’s believed to say. But in many other respects, it delivers just what it’s remembered for: the lavish, colourful sets and costumes often echoing 18th-century paintings, the atmosphere of old Vienna recreated by Forman and cinematographer Miroslav Ondříček in Communist Prague, the dominance of two larger-than-life characters, and of course the torrents of Mozart on the soundtrack.

Sometimes the music is diegetic, at other times not. Sometimes it switches roles, sometimes it’s in the composer’s mind. There’s one particularly impressive scene where Mozart’s dancing around his apartment, thumbing his nose at his father’s portrait to the backing of the Magic Flute overture (presumably in his head) when a sinister figure knocks at the door… and the soundtrack abruptly switches to the Commendatore motif from Don Giovanni, a much darker opera, mirroring the sudden change in Mozart’s mood. This may be an egregious case of Amadeus linking life to music too literally, yet it’s a masterful piece of theatre nonetheless.

Indeed, Amadeus is a very theatrical movie in every sense, right from the schtick with Salieri’s servants bringing him cakes at the beginning. So much so that it’s amazing playwright Shaffer wrote of its “naturalism” and the way it was “not a stagey hybrid”. For example, scenes are very clearly divided and often shot rather statically from a mid-distance, giving the audience a view roughly similar to a playgoer’s. And, of course, there are many actual staged sequences showing Mozart’s operas as well as one of Salieri’s. (For obvious reasons of visual interest, the film tends to concentrate on Mozart the opera composer, and there’s comparatively little of his orchestral or chamber music, for example.)

Amidst all this visual and aural grandeur, Amadeus delivers its ideas—or, more precisely, repeatedly reiterates its one big idea—through the script co-written by Forman and Shaffer. Several of the latter’s plays had already been adapted for the screen, most recently Equus (1977), and Amadeus the movie does take from Shaffer’s play the central notion of Salieri’s aggrieved reaction to Mozart. This was not an original concept: Pushkin had written Mozart and Salieri in 1830, with an opera by Rimsy-Korsakov following later in the 19th-century and a silent movie in the early-20th. But to modern audiences, it was primarily Shaffer’s idea and it was his Amadeus, rather than any earlier version of the tale, which rescued Salieri from obscurity.

All the same, the screenplay was written from scratch by both Shaffer and Forman over several months during which they lived together, and it departs from the play in major respects. Significantly, for example, the first word to be heard on stage is “Salieri” but the first word in the film is “Mozart”. The movie treats them more as co-stars, rather than focusing on the older man.

Yet what really compels is not so much the sometimes repetitive and often mannered script as the performances—particularly F. Murray Abraham as Salieri, a role for which he won ‘Best Actor’ at the Oscars. (Tom Hulce, as Mozart, was also nominated.) Especially persuasive is the contrast between the suave, outwardly confident, successful court composer of the 1780s and the elderly Salieri confined in an asylum many years later who, in a framing device, recounts to a priest the events leading up to Mozart’s death.

He’s decrepit and self-pitying at one moment, but then wily and dangerous like a cornered animal the next. “I speak for all mediocrities in the world, I am their champion,” he says, and you can’t be sure whether he feels ultimately victorious or defeated in his struggle with God.

Abraham’s performance is not devoid of hamminess, but it’s indisputably powerful. Hulce’s Mozart is even less subtle, though that’s clearly Forman’s and Shaffer’s intention rather than a failure on the actor’s part, and he’s most memorable for what Salieri describes as his “obscene giggle”. But he has great presence and, despite the caricatured way the role is written, he drops hints of depth into his character, especially when conducting. The childish vapidity ebbs away as he sickens toward the end of the film to be replaced by a convincing, urgent intensity; faced by death, Wolfie grows up.

Also strong in the cast are Elizabeth Berridge as his wife Constanze, more changeable in mood than Mozart; Simon Callow (in his movie debut) as Schikaneder, the cheerfully disreputable librettist of The Magic Flute; and Jeffrey Jones as Emperor Joseph II, played with a friendly aloofness that’s perfectly judged. Jones captures in his expression and his manner the emperor’s conflict when he’s intrigued by the idea of Figaro even while feeling he ought to ban it, and the amusement he seems to secretly harbour—though he won’t mention it—at the obsequiousness of his courtiers.

It’s probably no coincidence that several of these actors are better known as stage performers than for their screen work, and indeed Hulce’s movie career post-Amadeus was markedly low-key. He eventually abandoned acting to concentrate on producing and directing theatre productions. Abraham has worked in cinema more extensively, although he never became a huge star in the way his Amadeus success might have suggested. Even the Czech director Forman, who came to the project with the vastly acclaimed and profitable One Flew Over the Cuckoo’s Nest (1975) under his belt, made only a few more movies, none of them approaching this one’s prominence.

A Director’s Cut of Amadeus, released in 2002, added 20-minutes onto a film that was already 161-minutes long, restoring some scenes and extending others. Although one new sequence between Salieri and Constanze clarified an aspect of their relationship that wasn’t quite clear in the original—the extent to which he had tried to seduce her—the Director’s Cut made relatively little impact. It gained some positive reviews but many others suggested that Mozart’s famous line about a piece of music having exactly the right number of notes, neither too many nor too few, could be applied to the original film too.

That reference to perfection may be praising the 1984 version too far. Even if the non-narrative aspects like design and music are superb, and individual scenes are never less than engaging, 35 years later there’s a sedate staginess and lack of naturalism that gives Amadeus a dated air. That is not a fatal flaw—it affects many classic movies, after all—but it does mean that Forman’s film isn’t as fresh and stimulating in 2019 as it struck audiences in 1984.

Equally importantly, for a modern audience already familiar with the whole Mozart-Salieri myth, there’s not as much to surprise us as there was back then. So the point can feel hammered home once too often. This is the real problem with Amadeus: it has only one idea which everything else serves. When that idea ceases to be intriguing and novel to more educated viewers, so does much of the film.

Yet what makes it still worth seeing is not (as its creators might have believed) the philosophising, but the performances, especially Abraham’s—rising above the limitations of the script and bringing us a human Salieri who we can at least half believe in, a strange and memorable antihero.

director: Miloš Forman.

writer: Peter Shaffer (based on his stage play).

starring: F. Murray Abraham, Tom Hulce, Elizabeth Berridge, Simon Callow, Roy Dotrice, Christine Ebersole, Jeffrey Jones & Charles Kay.