MURDER BY DECREE (1979)

Sherlock Holmes investigates the murders committed by Jack the Ripper and discovers a conspiracy to protect the killer.

Sherlock Holmes investigates the murders committed by Jack the Ripper and discovers a conspiracy to protect the killer.

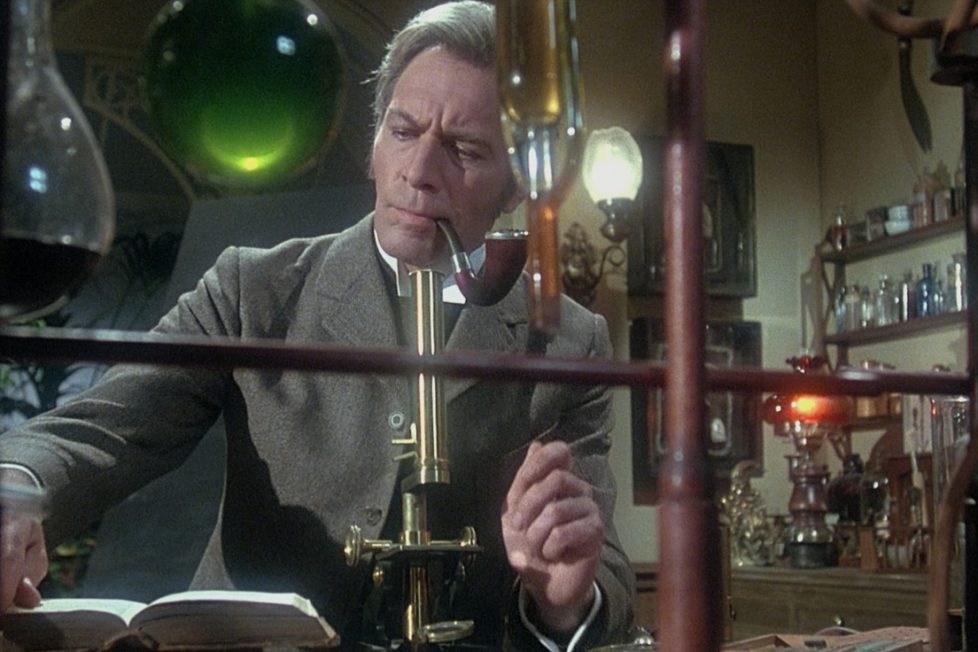

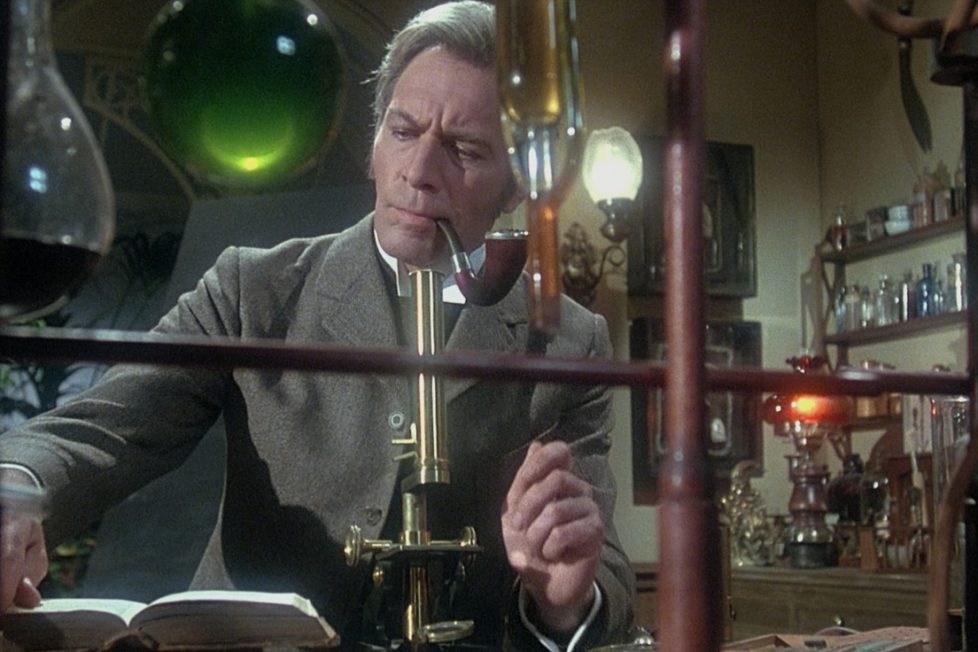

A clever fusion of fact and fiction blending several genres, Murder by Decree remains one of the best big-screen portrayals of Holmes (Christopher Plummer) and Watson (James Mason); here pitting their wits against infamous serial killer ‘Jack the Ripper’. Over the years, I’ve talked with plenty of people who think Sherlock Holmes was a real person, and it’s true we know far more about Holmes than we’ll ever learn about Jack the Ripper.

What we do know about Jack is generally guesswork. He may even have been more than one person. So, our idea of him is just as much a fiction, if not more so! On the other hand, the lives of Holmes and Watson are just as entangled with real places and events. They’ve become a part of London lore; a meme of the collective imagination. Tourists can even choose between Sherlock Holmes and Jack the Ripper tours of the capital, visiting real locations associated with both men. It’s only natural then that these characters would end up running into each other. Which they have done several times on page, stage, and screen…

Ever since his reign of terror in the London of 1888, Jack the Ripper’s fascinated the public because his crimes (the murders of at least five women) were so horrific and sensationalised, back when he was simply known as ‘the Whitechapel murderer’. Also, he was never brought to justice, so criminologists and amateur sleuths continue to try and solve the mystery and uncover his identity to this day. ‘Ripperology’ became a highly marketable genre! There are hundreds of books written on the subject and Jack’s shown up in numerous movies since his first surreal screen appearance in Paul Leni’s Waxworks (1924).

There was a peak of interest in the mid-1970s with the publication of a new theory expounded upon in the book Jack the Ripper: The Final Solution. Its author, Stephen Knight, had tied the murders to an intricate conspiracy involving the power-play of opposing political factions, secret societies, the Prime Minister, and even the Royal Family. He suggested the murderer was a high-level court physician and the killings were central to an elaborate plot intended to silence just one of the victims and cover-up a royal indiscretion. Knight’s theories were certainly woven around a compelling bunch of facts, but he’d also introduced considerable conjecture to make them fit the pattern he’d invented.

Knight’s work of fiction, loosely based on some historic evidence, was partly the inspiration for Murder by Decree, but director Bob Clark was disappointed that the central theory was so quickly contested and discredited. So, when he began working on the screenplay with writer John Hopkins, they turned to another book—The Ripper File by John Lloyd and Elwyn Jones—which was published in 1975 as a tie-in with the BBC docu-drama Jack the Ripper (1973). The series starred Stratford Johns and Frank Windsor, reprising their characters of DCS Charlie Barlow and DCS John Watt, respectively, who were famous from the classic police drama series Z Cars (1962-1978). The inventive format had them poring over the unsolved case files, illustrated with dramatised inserts of the historic events. John Hopkins and Elwyn Jones had both worked as writers on Z Cars and Hopkins went on to write Thunderball (1965).

Bob Clark had already directed a handful of exploitation and horror movies, including Children Shouldn’t Play with Dead Things (1972), and Black Christmas (1974), the psycho-Santa thriller that also involved a string of unsolved murders. He was working on a John Carpenter script, Prey, when that project fell-through due to casting difficulties. So, he was suddenly free to pursue his Ripper ideas, with Hopkins penning a script titled Sherlock Holmes and Saucy Jack. After six extensive re-writes, they’d settled on a new title: Murder by Decree.

Their premise was to reinvent the Holmes and Watson dynamic by making them both more human. Holmes would be a man with emotional intelligence, relying as much on psychological understanding as clinical deduction. Watson would prove to be a stable, stolid support. Though there’s plenty of wit and repartee in their relationship, there would also be a genuine affection between them and Holmes wouldn’t be condescending toward his companion. The entire film depended on how these two lead characters were played.

Although Peter O’Toole and Laurence Olivier had been the first choices, the pairing of Christopher Plummer and James Mason proved to be perfect. They manage to believably convey everything that Clark and Hopkins had hoped for, and more. They’re joined here by other members of the thespian elite, in a most impressive cast of British and Canadian talent. We have Frank Finlay playing Inspector Lestrade, either as an incompetent or someone in fear of losing his job but not as the usual comedic bumbling stereotype. And in a key scene, John Gielgud plays the Prime Minister with suitable Victorian gravitas… or should that be pomposity?

Anthony Quayle plays Sir Charles Warren, one of the few real, named historical personages to appear here, as an infuriatingly self-serving villain. It seems that may be a true representation as the real Warren was Commissioner of the Metropolitan Police and generally seen as responsible for the Bloody Sunday riots of November 1887, when protesters clashed with police, cavalry, and army. Many were injured on both sides and there were hundreds of arrests.

The riots were led by ‘radical socialists’ and the Irish National League, sparked by a number of circumstances—including rising unemployment, economic depression, and new laws being passed to suppress escalating unrest in Northern Ireland. The funerals of activists killed in the riots sparked further clashes. However, these didn’t serve their cause and the sitting Tory government used the violence and its aftermath to vilify their political opponents. This is all touched upon by Murder by Decree and feeds into the storyline. Indeed, the real Sir Warren lost his position due to his ineptitude at bringing in Jack the Ripper. It seems that either the Ripper investigation was incredibly mishandled throughout, or more likely, there were influences at play that did not want the killing stopped or the killer caught… but why?

Donald Sutherland turns in one of the more subtle and intriguing performances of the piece as the psychic Robert James Lees. Lees is another real person associated with the historic case, who claimed to have learned the identity of the Ripper through his visions and divulged his suspicions to the authorities. Surprisingly, Holmes visits the spiritualist and takes him seriously, as does Inspector Foxborough (David Hemmings), a policeman who may not be all that he seems as he’s prepared to manipulate the investigation for his own political ends.

Plummer’s Holmes is one of the best and easily on par with Robert Stephen’s inspired interpretation in Billy Wilder’s The Private Life of Sherlock Holmes (1970)—an equally brilliant, though decidedly different treatment of the character. It’s interesting that neither of the two best cinematic versions of the iconic character are technically canon and neither are based on stories written by Holmes’s creator Sir Arthur Conan Doyle. Also, both give us a more human and emotionally invested man with a deep empathy for others and genuine affection for his friend, Watson. Incidentally, Mason’s version of Watson is also top-notch, beautifully nuanced and complex.

The two female leads were filled by Canadians with Susan Clark as Mary Kelly and Geneviève Bujold as Annie Crook. Both are excellent and, although Bujold only appears in a single scene, it’s one of the most crucial in terms of plot and arguably the most brilliant showcase of bravura acting among several here. The international cast came with the funding as an international coproduction, with Canada contributing $3M and the UK topping it up with and extra $2M.

The look of the film is wonderful, evoking Victorian Gothic with London streets so dark and foggy it must’ve saved a fortune on building sets! What we do see of the extensive sets constructed at Shepperton Studios are fantastic, and enhanced with extensive miniature work for the cityscapes that help build a pervasive, dream-like strangeness. Cinematographer Reginald H. Morris was already a regular collaborator with Bob Clark, and used to making the most of what he’d be given on a comparatively modest budget. He also made good use of dilapidated, though still standing, London locations that were to disappear over the next few years under a wave of yuppy-powered gentrification.

Morris is clearly fond of wide lenses, used here to imply a distortion of reality—either due to the madness of Jack, or the contrived conspiratorial meddling by the powers that be. He’s certainly not afraid of shooting in low-light and, at times, the screen’s almost entirely consumed by oppressive darkness. Equally, there are scenes when lamps or windows glare into a haze of brilliance. This high contrast may be an artefact of 1970s stock and equipment, but it’s exploited here as a narrative device, to highlight the dualities of good and evil, class division, the public and the private, the unknown and the intentionally obfuscated.

The plot of Murder by Decree is deliberately complex, yet meticulously laid out for the viewer to unpick along with the pair of protagonists. Also, just as Holmes has to, we must engage our emotional and intellectual faculties to get the most out of the story. At times, it’s the emotional side that wins out and don’t be surprised if there’s a surreptitious tear here and there. It’s a testament to the power of the performances. The apt score by Canadian composer Paul Zaza and his collaborator Carl Zittrer, certainly help with some heartfelt themes and perfect cues, but I think it’s mainly Plummer’s voice, especially when words and music join forces during the incredible emotive monologues in the third act.

For what it is, Murder by Decree is near perfect from beginning to end. So, it may be surprising to learn it didn’t do well on initial release. Box office was brisk to begin with but soon tailed off and the film only managed to recoup about half its budget. Various reasons have been put forward for this. One is that it was perhaps a little too sombre, though there’s no denying it has some clever comedy elements. Maybe it was too clever? But everyone who’s seen the film will fondly recall the beautifully delivered scene where Watson utters the line “but, to squash a fellow’s pea.”

Another possible reason might have been the release of Time after Time (1979), an excellent film also featuring Jack the Ripper, who steals H.G Wells’s time machine and escapes from Victorian London to modern-day San Francisco. Nicholas Meyer’s enjoyable time-traveling romp was clearly a genre piece and could be marketed as such. Murder by Decree is definitely a horror film—the scene where Holmes stumbles upon the final grizzly murder scene remains as effectively shocking today—but it’s perhaps too mainstream and subtle for a ’70s audience with more Hammer horror expectations. As Kim Newman puts it in the commentary, the Victorian London of Murder by Decree has no “Knees up, Mother Brown and cockney sparras!” For all its stylistics and thick atmosphere, it remains grounded in real human emotions and manages to make its unlikely plot rather too convincing.

Distribution problems, associated with the rights retained by the BBC, have also been blamed. And while this may be the case, the BBC had exclusive early rights to screen the film, so it became a regular event on UK late-night TV throughout the 1980s. Many viewers saw it when they were perhaps a bit too young and it left an indelible impression that ensured its cult status only grew over the years. Which is why it’s great to get this newly restored Blu-ray release from StudioCanal’s ‘Vintage Classics’ catalogue…

UK • CANADA | 1979 | 124 MINUTES | 1.85:1 | COLOUR | ENGLISH

The audio and picture are better that ever, taken from a new 4K digital scan. Scratches are cleaned up and colour tone nicely graded, but there’s an occasional vertical artefact that must be present on the best available print. It doesn’t distract from the absorbing narrative and won’t be noticed unless you’re looking for it.

director: Bob Clark.

writer: John Hopkins (based on ‘The Ripper File’ by John Lloyd & Elwyn Jones, and ‘Sherlock Holmes’ characters created by Sir Arthur Conan Doyle).

starring: Christopher Plummer, James Mason, David Hemmings, Susan Clark, Anthony Quayle, John Gielgud, Frank Finlay, Donald Sutherland & Genevieve Bujold.