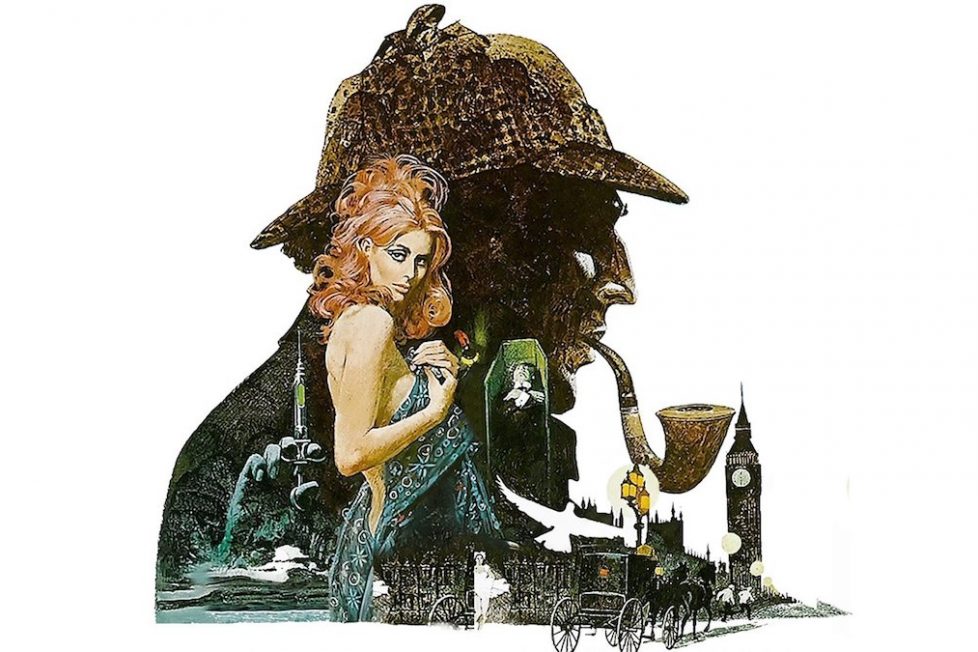

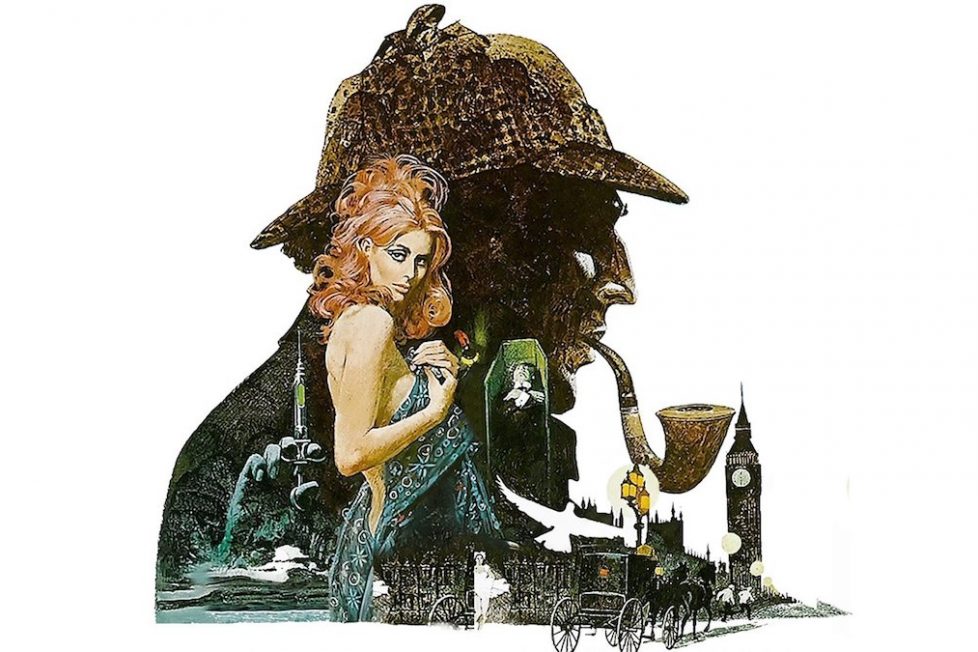

THE PRIVATE LIFE OF SHERLOCK HOLMES (1970)

When a bored Holmes eagerly takes the case of Gabrielle Valladon after an attempt on her life, the search for her missing husband leads to Loch Ness and the legendary monster.

When a bored Holmes eagerly takes the case of Gabrielle Valladon after an attempt on her life, the search for her missing husband leads to Loch Ness and the legendary monster.

I first saw The Private Life of Sherlock Holmes on TV when I was about 10-years-old, and it left an indelible impression. It’s what gave me my love of most things Sherlockian and set the benchmark for what I expected from a Holmes story. Ironic, when you consider that it’s not adapted from any of the original Arthur Conan Doyle stories, although it does weave in many references to them.

The premise is that some of the exploits of Holmes and Watson were just too delicate to be published in The Strand magazine; either because they were politically provocative, or simply too personally embarrassing, and should only be read posthumously. So, Dr. Watson consigned them to a tin dispatch box to be held in a London Bank, with instructions that it be opened 50-years after his death. The ensuing Gothic plot takes us from the streets of Olde London Town to the highlands of Scotland, piecing together a baffling puzzle involving white canaries, missing midgets, hooded monks, German spies, the Loch Ness Monster, ruined castles, a steam-punk submarine, even Queen Victoria herself! What more could one ask?

Billy Wilder, who read all the Conan Doyle stories as boy, shared a deep love for the Sherlock Holmes milieu with his writing partner I.A.L Diamond, and they’d been working towards the Private Life script for more than a decade, which explains why the film is so perfectly formed and cohesive. Prior to this version, the scripts had gone through many incarnations. One was planned as a musical with Rex Harrison in the lead, à la My Fair Lady (1964); indeed Wilder had approached the same songwriting team, Alan Jay Lerner and Frederick Loewe. Fortunately, perhaps, this idea fell through, because the film we have showcases the passion of the writers with every line of delightful dialogue.

Private Life is trying to get to grips with how Dr. Watson sees and writes about his friend, and what a ‘real’ Holmes may have been like. The depth of characterisation is what you’d expect from Wilder, one of the truly great writer-directors, responsible for a string of classics. These include my favourite Barbara Stanwyck comedy, Ball of Fire (1941), noirs like Double Indemnity (1944), The Lost Weekend (1945), Sunset Boulevard (1950), romantic comedies like Sabrina (1954), Marilyn Monroe movies The Seven Year Itch (1955) and Some Like It Hot (1959), acerbic Jack Lemmon romps like The Apartment (1960) and The Front Page (1974), and the mysterious Fedora (1978). He had a varied filmography of more than 80 titles, many of which he co-wrote with Diamond.

On release, his Sherlock Holmes movie flopped. Audiences rejected it, and it’s a real challenge to find any favourable reviews from 1970. It just wasn’t what audiences expected: not really a spoof (as it’s still sometimes described), not a familiar Rathbone-style heroic adventure, not a cosy crime caper and, although there are some scenes played for laughs, it’s not an outright comedy. It may well be the most serious, and I believe successful, attempt to get to the heart of the Holmes character ever attempted. I will always maintain that Jeremy Brett’s portrayal, in the long-running ITV drama series, is the definitive version, in terms of the literary Holmes, but Private Life’s Sherlock is the one I think of as the real character. The man behind the myth, as it were, and certainly a Holmes I would like to have known.

The great British actor, Robert Stephens, plays Holmes with a generous dose of the ‘Oscar Wildes’, and manages to imbue him with a deep humanity, fluctuating between overbearing arrogance, subtle irony, needle-sharp wit, scintillating sarcasm, touching sensitivity, surprising kindness and, at times, the deepest melancholia. The film doesn’t shy away from his cocaine addiction and was the first to explore this explicitly, six years ahead of The Seven-Percent Solution (1976). It’s a masterful character study that adds as much to, as it takes from, the original canon.

Wilder pushed for Stephens to be cast in the lead after seeing him in The Prime of Miss Jean Brodie (1969) because he played Teddy Lloyd, an intellectual yet vulnerable teacher. Wilder wanted a Holmes that “looked like he could be hurt.” Peter O’Toole was the only other contender, presumably because of his performance in Goodbye Mr. Chips (1969), which has some parallels.

Wilder wanted his Holmes and Watson to have a deep rapport, so it was Stephens who suggested his friend, Colin Blakely for the role. Blakely interprets Watson as a passionate, energetic character—a ‘man’s man’, full of bravery and bluster, with just the merest hint of buffoon brought out by great physical acting as he often fumbles and stumbles his way through the action.

To some extent, Holmes and Watson now look upon each other with envious eyes. Watson wishes he was more coolly analytical whilst Holmes would like to be able to just let go… and have as much fun as his best friend. It’s a bit like Spock’s logical intellect being the perfect foil for Captain Kirk’s gung-ho heroism, though both needing the other to be complete.

This counterplay between the two characters, and their conflicting characteristics, pinions the whole story. Far from being the cold, emotionless, “calculating machine” we often see, Watson describes Holmes as, “the most brilliant man I had even known, and the most infuriating: moody, egocentric, and altogether unbearable…” In other words, not at all cold and distant, but an emotionally volatile individual, seeking pure intellect as a refuge from inner turmoil. Perhaps a deep emotional scar he may have suffered in the past?

The film doesn’t avoid the gay subtext, either. In order to extricate himself from a potentially intimate situation involving a Russian Prima Ballerina, Holmes claims to be living with Watson, rather than simply sharing lodgings. The outraged Watson confronts him with a question, “I hope I’m not being presumptuous,” he says, “but, there have been women in your life?” to which Holmes replies “the answer is, yes” before adding “you’re being presumptuous.” This gender-centric theme becomes central to the whole film…

Enter Gabrielle Valladon (Geneviève Page), a young lady rescued from the Thames by a cabby and delivered to 221b Baker Street, still clad in her torn, wet and clinging dress, with no memory of how she came to be in London. Later in the story, Holmes and Valladon assume the aliases of Mr. and Mrs. Ashdown, sharing a sleeper carriage on the train to Scotland. In this scene, Holmes chooses to share several accounts of his rather racy, and ill-fated, affairs with quite a catalogue of, shall we say, ‘interesting’ women including concubines, murderers, and a succession of ‘maniacs’: klepto-, pyro- and nympho-, not to mention the rather tragic tale of his fiancé. We get a small glimpse as to where his mistrust of the ‘fairer sex’ may have originated, though it also becomes clear that he is still certainly susceptible to the womanly wiles and charms of his attractive travelling companion.

The other pivotal player in the conspiracy is Holmes’ older, and supposedly intellectually superior, brother Mycroft (Christopher Lee). Lee was no stranger to the world of Holmes, having appeared in Hammer’s adaptation of The Hound of the Baskervilles (1959) as Sir Henry, and playing Sherlock Holmes himself for an obscure foreign production called Sherlock Holmes and the Deadly Necklace (1962). He would go on to play Holmes twice more in Sherlock Holmes and the Leading Lady (1991), and Incident at Victoria Falls (1992). George Sanders and Laurence Olivier were both considered for the part, but apparently Wilder and Diamond wanted Lee, who didn’t even test for the part. They also insisted that he look unrecognisable, so he was made-up using a bald-cap, to have less hair than he did once he reached the age of 90!

The prolific Christopher Lee made 10 films that same year, though this one was something very special. This new Masters of Cinema edition from Eureka Video, includes an informative archival interview, giving insight into the production, from casting to completion. He claims it was an experience that changed his life as an actor, praising Wilder as the greatest director he ever worked with. Lee’s distinctively rich voice is always a pleasure to listen to and this bonus, though just 15-minutes long, is pretty in-depth with hard facts and plenty of personal reminiscences. Which brings me to the extras…

I don’t think I’ve ever been so excited about extras before! A ‘lost prologue’, shared here in the form of script pages interspersed with archive stills, has a Dr. Watson, who turns out to be the grandson of ‘our Watson’, visiting from Canada where he practises veterinary medicine… The props seen in these stills do appear in the final version of the opening titles, redesigned by Maurice Binder (famed for his epic opening credits for James Bond). The words, read aloud from a letter, become their scene-setting narration.

It seemed the film was originally to introduce Holmes and Watson with a vignette on a train, when Holmes demonstrates his prowess in observation and deduction by solving a case solely form noting the attire of a fellow traveller—there is some fine, sharp dialogue that helps to establish the characters and repurpose them for this fresh insight to their relationship.

Another deleted scene, from early on, features Inspector Lestrade showing up at Baker Street, finding Holmes playing violin in his nightshirt, and letting slip a red-herring about six anarchist midgets attempting to assassinate the Tsar… He then procures Holmes’ help in solving ‘The Curious Case of the Upside-down Room’. The delicious archive photographs are visually striking, and the segment serves as a stand-alone episode that could have been the pilot for a television series! The solution that Holmes finds to this particular lost case lays out a huge slab of character development that would have informed the viewer’s approach to rest of the film, and it certainly contributes a fresh twist to the relationship of Holmes and Watson. “In my cold, unemotional way, I am very fond of you, Watson.”

The extended scene of Sherlock and Gabrielle sharing the sleeper car was planned to include a flash-back to Holmes’ college days and his first romantic infatuation, which ends with a tragi-comic twist. Even without this material, the scene as it survives gives plenty of background to the Great Detective’s interactions with women, hinted at, though barely touched upon in the original stories.

In another missing minisode, The Dreadful Business of the Naked Honeymooners, Dr. Watson plays the central part in (not) ‘solving’ the case “with consequences that were nothing short of devastating.” This segment was filmed and has survived in its entirety, but with no sound. It can be enjoyed here as a silent movie with subtitles and provides more than a few good laughs. It would have been the film’s most comedic set-piece…

These ‘lost cases’ show how seemingly superhuman and infallible Holmes is, whereas the main story reveals his very human traits, including fallibility. They form a sort of mini-series in themselves and it is a shame they were never completed. They would have added nearly an hour to the run-time, so I expect it was decided that a three-hour film would have met with even more resistance from the distributors and audiences of the time.

It would have been great to see these missing episodes restored, given the ‘Doctor Who treatment’, and presented as animations. Or even a mini-comic included as part of the package. How cool would that have been! Such a shame it was before the days when discarded footage was valued and put aside for possible DVD extras. I would love to see the director’s cut as originally intended by Diamond and Wilder. Although the film is a stone-cold classic and near perfect as is, it would be nice to have more of it! I believe the original vision would have been an even greater contribution to the Sherlock Holmes heritage.

It seems only the audio survives of the one minute ‘epilogue’ included here: Lestrade calls at 221b Baker Street, to bring a series of murders, attributed to a certain ‘Jack the Ripper’, to the attention of Holmes who’s otherwise occupied with his 7% solution. Watson assures the inspector that Scotland Yard should have no problem solving the case on their own! Perhaps this was best left out, as it would have diluted the poignancy of the final scene… Though I like to think this was the inspiration for my other favourite Sherlock Holmes movie, Murder by Decree (1979), which I consider to be a, somewhat more sombre, sequel.

Instead of a commentary, the package includes some worthwhile interviews. Ernest Walter, the editor, tells us how he started as a wartime army cameraman and then trained at MGM Borehamwood. Private Life of Sherlock Holmes was one of the 20 or so feature films he went on to cut. He’s very thorough and comments on many of the key scenes and, along with the likes of Christopher Lee, remembers working with Billy Wilder as an important experience, the film being the highpoint of his career. Although now in his seventies, he remembers the experience in surprising detail, correcting a few things that have been previously misreported, and places the film into a context of the film industry at the time. I think the curved Sherlock-style pipe he clutches and gestures with during the interview is actually his, and not some prop he grabbed. The interview runs to 28 minutes, but I could have listened to him for hours…

Neil Sinyard, Professor of Film Studies at the University of Hull, gives an excellent and well-considered talk about why the film is so relevant today, perhaps more so than on its release. He gives plenty of opinion, well-researched titbits and discusses the subtleties of the extensive subtext. Well worth a watch and a welcome inclusion with this Blu-ray release. One particular nugget was that Wilder, in the 1950s, had been at a performance of a violin concerto written by veteran soundtrack composer, Miklós Rózsa. Afterwards, he had commented that the music sounded like something Sherlock Holmes may have played. He was taken with its moments of light-hearted humour and deep melancholy and told the composer that one day he would write a film around the ideas the music had inspired in him. So, it is fitting that Rózsa, who had worked with Wilder several times since the 1940s, wrote the highly evocative score for Private Life of Sherlock Holmes and makes a brief cameo as the conductor of the orchestra in the Russian Ballet scene.

It was a pleasure to watch a lovely high-definition Blu-ray copy. The picture quality does fluctuate a bit, and colour saturation’s a little inconsistent, but Eureka assure us their Masters of Cinema editions are always duplicated from the most recent re-maters or the “most pristine” prints available. Besides, I enjoyed the tiny scratches and glitches which threw me right back to seeing it for the first time, with the bright young eyes of a ten-year-old!

The Private Life of Sherlock Holmes is a brilliant piece of cinema. It has certainly inspired and informed nearly all the subsequent interpretations, and perhaps remains the finest of them all. A must-see for anyone with a passing interest in Sherlock Holmes and there’s something to appeal to the whole family. It’s so good, I would wish I could forget it entirely, so I could enjoy it for the first time again. This may not be possible, but now, with this beautiful Blu-ray package, I can at least relive it as often as I like!

director: Billy Wilder.

writers: I.A.L Diamond & Billy Wilder.

starring: Robert Stephens, Geneviève Page, Colin Blakely & Christopher Lee.