WAXWORKS (1924)

A wax museum hires a writer to give the sculptures stories. The writer imagines himself and the museum owner's daughter in the stories.

A wax museum hires a writer to give the sculptures stories. The writer imagines himself and the museum owner's daughter in the stories.

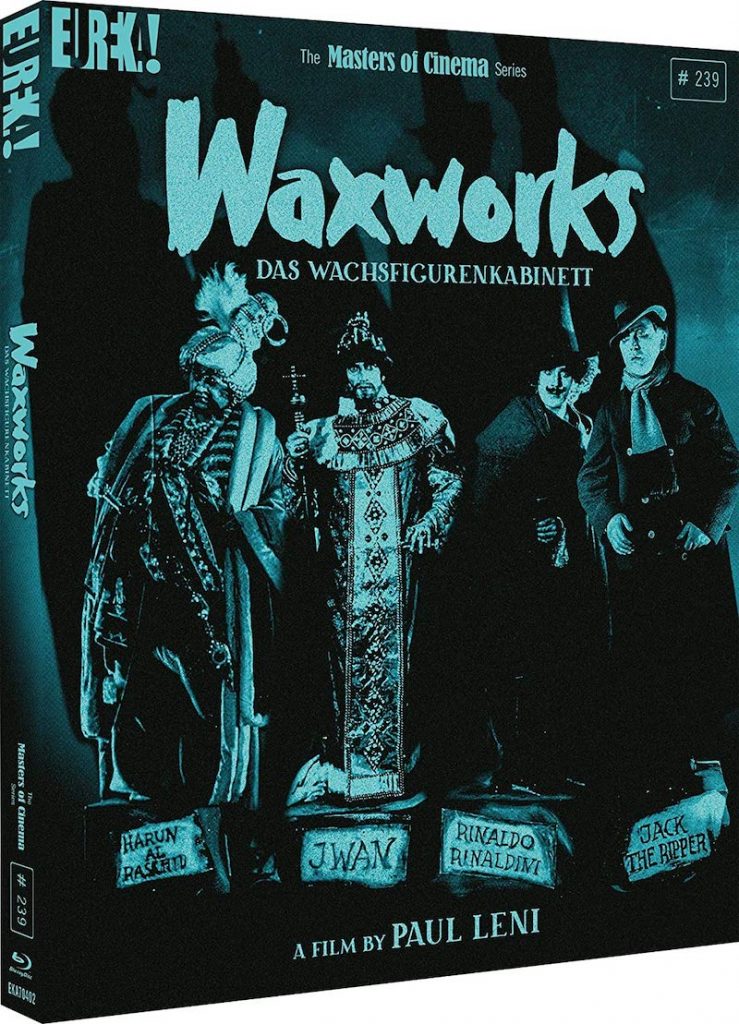

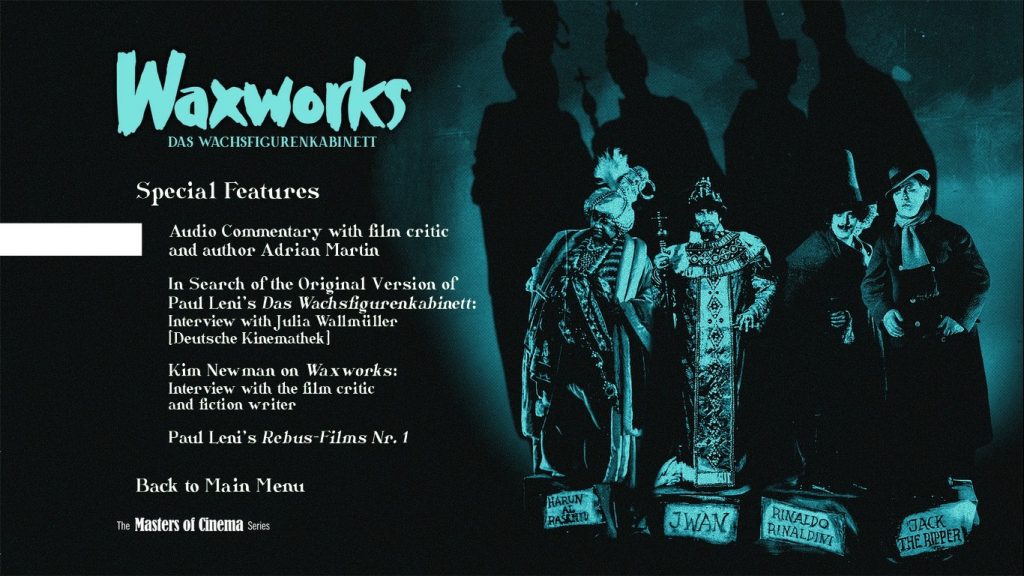

Horror fans will be familiar with the ‘waxworks’ trope, though few will have seen Paul Leni’s seminal film, Waxworks / Das Wachsfigurenkabinett. That’s because the original movie no longer exists. Like many films made during Germany’s interwar period, it was thought lost, but after an international effort, here it is on Blu-ray! And hot on the heels of Leni’s classic interpretation of Victor Hugo’s The Man Who Laughs (1928), it’s joining Eureka Entertainment’s ever-expanding ‘Masters of Cinema’ catalogue.

Waxworks is an early example of the horror portmanteau, being an anthology of three tales told within a framing coda. A poet (William Dieterle) has been drawn to a fairground by a classified ad in the newspaper: ‘WANTED—An imaginative writer for publicity work in a waxworks exhibition.’ Well, what writer could resist? He finds the sideshow tent and is welcomed by the proprietor (John Gottowt) and his happy, attractive daughter (Olga Belajeff).

The job entails writing “startling stories” about three (or four) historic figures immortalised as wax statues—so real that they’re actually played by actors. We’re introduced to Haroun-al-Rashid (Emil Jannings), Ivan the Terrible (Conrad Veidt), and a figure introduced by caption as Spring-Heeled Jack (Werner Krauss). Observant viewers may note his pedestal is labelled ‘Jack the Ripper’.

That’s quite a cast for the time! Those with an enthusiasm for silent horror will know John Gottowt as Professor Bulwer, the Van Helsing character in F.W Murnau’s Nosferatu (1922), and Werner Krauss as the titular mesmerist in The Cabinet of Dr Caligari (1920), which also starred Conrad Veidt as his zombie ‘somnambulist’, and Emil Jannings appeared in Murnau’s Faust (1926).

The opening shots of carousels, drumming clowns, top-hatted gents, and bustling punters, are dreamlike yet dynamic—created with an overlay of imagery reminiscent of contemporary German Expressionist painters. The busy, neo-cubist compositions of George Grosz or Otto Dix, perhaps?

German Expressionism was a product of a national aspiration. It embodied an ideal of social equality, whilst addressing the problems that had led Germany into World War I and its dire aftermath. It was the art of the nascent Weimar Republic, attempting to map-out a new German identity before the nation’s economic failure. Sadly, the reactionary Nazi Regime were on the rise and would deem it ‘degenerate’, but not before the style had left its indelible mark on world cinema.

Early German Expressionist films grew from a spirited response to miniscule budgets. It wasn’t long after the dawn of cinema, so there were no established conventions anyhow and filmmakers were creatively unfettered. For a time, theatres were banned from showing foreign films, and yet the public were flocking to the picture houses as a cheap form of entertainment as the value of their Deutschemarks rapidly declined.

To meet the demand, studios welcomed any measures that could cut costs. Painted sets and backdrops were cheap. Thing is, they’d look cheap unless something inventive was done with them. Letting go of the pretense of realism and embracing the Expressionistic approach meant that painting windows, doors, objects, in an exaggerated manner, with dramatic distortions created some striking sets. Only essential props were needed along with suitable costumes and some clever lighting to emphasise the contrast with deep chiaroscuro shadows, thus concealing a multitude of shortcomings.

It wasn’t long before Expressionism became the style of choice rather than necessity, and 1920 saw filmmakers positively embracing it with a handful of definitive productions: Karlheinz Martin’s darkly stark From Morn to Midnight / Von Morgens bis Mitternachts (1920), Paul Wegener’s Golem films of which The Golem: How He Came into the World (1920) is the only surviving version. The Cabinet of Dr Caligari may be the best-known example, though director Robert Wiene would also bring us another Expressionist classic with The Hands of Orlac (1924)—both starring the amazingly versatile Conrad Veidt, who also steals the show in Waxworks.

The first story in this loose trilogy is of Hasoun-al-Rachid, the corpulent Caliph of Baghdad. His mannequin needs repair as an arm has fallen off. The writer finds instant inspiration, as he’ll tell how Hasoun lost his arm. A great hook!

How we use stories in different ways, in different situations, is key to the narrative of Waxworks. The proprietor picks-up instantly on the chemistry between his daughter and the writer. He seems to approve as he makes himself scarce for a while. In placing the advert, he’d already acknowledged the power of stories to stimulate the imagination and engage his sideshow audience. The initial motivation of the writer seems to be using his storytelling prowess to impress the daughter. So here we have a showman wanting to attract punters, a man trying to impress a woman, a writer hoping to please his readers, a director impressing his audience.

The tale we’re told has nothing to do with the great first century Caliph, Hārūn Ar-Rašīd, who founded the House of Wisdom during Baghdad’s golden age, and more to do with the fictionalised character he inspired in The One Thousand and One Nights—perhaps the original portmanteau which collected stories about Aladdin, Ali Baba, and Sinbad, which also dealt with the power of storytelling itself.

The writer places himself in the story as Assad a Baker of Baghdad, who’s trying to demonstrate his virility by vigorously kneading his dough while his beautiful wife, in the form of the proprietor’s daughter, watches. Now, I wasn’t expecting this ‘Dick Emery’ level of campness but the first segment, which will take us past the mid-point of the total 81-minute runtime, is only just getting started.

He becomes so distracted that he burns his bread. The smoke drifts over rooftops to where the Caliph is playing chess and gets the blame for putting him off his game. He’s a sore loser and orders his Vizier (Paul Biensfeldt) to ensure the Baker is sent to meet Allah forthwith. But, before he gets round to the execution, he’s also so distracted by the beauty of the Baker’s wife that forgets why he was visiting them…

Next, we graduate to almost Carry On levels! Once the bread’s in the oven, the couple can contain themselves no longer and in a rather risqué clinch, the Baker leaves embarrassing floury handprints on the bodice of his wife’s dress. Yes, that old chestnut! She’s not too happy about it though, complaining that she only has the one dress and she’s fed-up of being so poor even though her husband works day-in day-out. So, he sets off, Thief-of-Bagdad-style, to prove his manhood by stealing the Caliph’s famed wishing ring for her.

I must admit that, though it raised a smile or two, the first segment does drag a bit, at least to begin with, but it’s worth sticking around. Once you get used to the deliberate pacing, sink into the painterly cinematography, enjoy the flowing sculptural sets, and forgive the Les Dawson-style gurning of Emil Jannings, the fairy tale is exceptionally well-crafted with a satisfying climax that’s both complex and clever. There’s a spattering of horror elements, but at heart, the first half of Waxworks is a well-meaning broad comedy.

Not so the second instalment! The waxwork’s proprietor returns to wind-up his mannequin of Ivan the Terrible, which is an automaton. It’s uncannily life-like and destined to repeat the same actions over and over as it cranks a revolving tableau showing scenes from the life of the Russian ruler.

The idea of inescapable destiny and the repeating of a fruitless set of actions sparks another story idea for the poet. This time there aren’t many laughs to be had—in fact, the second tale is decidedly and deliciously grim. The writer begins, “Ivan was a blood-crazed monster on a throne, who turned cities into cemeteries. His crown was a tiara of mouldering bones, his sceptre an axe. His council-room was a torture chambre, with the Devil and Death as chief ministers.” I could see that becoming a meme to comment of the politics of today!

The outrageous portrayal of Hasoun already established that this is not a historical film and the version of Ivan has nothing to do with biography either. It’s about as authentic as Christopher Lee’s Dracula was to Vlad the Impaler, and I wouldn’t be surprised if Lee took some tips from Conrad Veidt’s performance here, which has definite vampiric undertones.

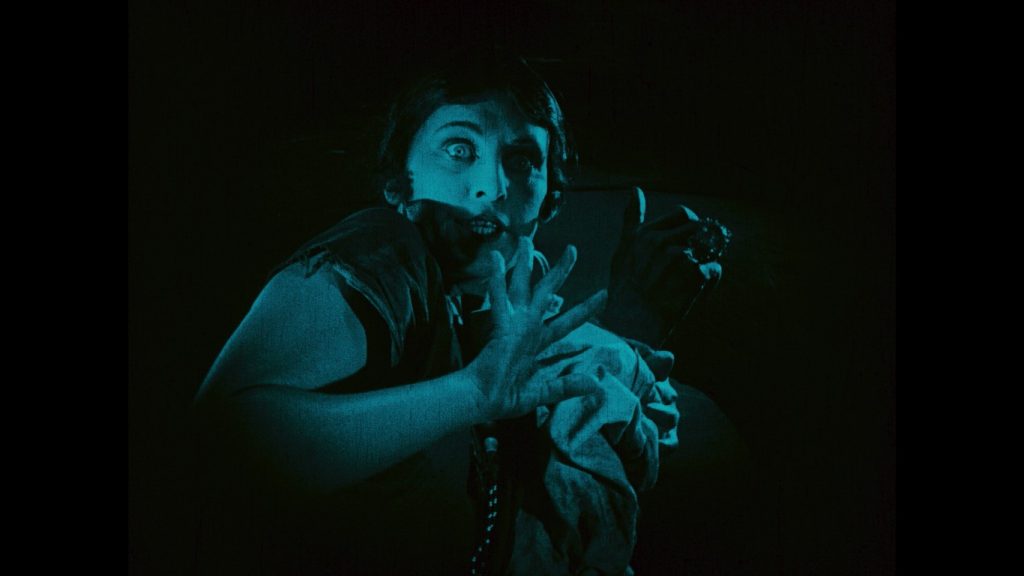

This time, the writer enters the story as a Russian Prince and the daughter is his betrothed. This segment is superbly creepy and delirious with smoky textures and deepest shadows from which emerges the attenuated figure of Conrad Veidt, possibly the greatest actor of German Expressionism. At times, his face looks almost animatronic, he seems to be able to inflate his veins at will… and his eyes!

He fills the scene with his presence whenever he’s in shot and his eyes seem to be illuminated from within. It’s impossible to look away. Of course, all silent acting is a form of expressive mime, all about gesture and body language, but Veidt takes it to the next level. In one scene, he’s animalistic and stooped as he accommodates low doorways, then towering over the proceedings in the next.

Ivan rules through fear and only really loves his alchemist (Georg John) for his deadly skill in mixing poisons. There’s a fantastically sadistic plot device where the poisoner inscribes the name of a victim on a huge hourglass and measures the dose so precisely that he guarantees that death will occur when the last grain of sand settles.

The scene when Ivan watches, his eyes flicking back and forth between a dying victim and his hourglass is perhaps overstated, but effectively chilling regardless. The way Veidt moistens his lips and shudders with orgasmic anticipation is truly terrible. The cruel actions and creeping insanity of Ivan bears a resemblance to the fanatical Stalin, who had just taken office as General Secretary of the Soviet Union a couple of years prior to the film. Likewise, he’s riddled with paranoid delusions, and Ivan begins to fear the power of his master poison mixer.

This is another great story, and it doesn’t drag for a moment. The ending is as inventive, philosophical, and satisfying as any short tale from all the horror portmanteaus that followed. The look is quite different from the Hasoun segment, although some formal motifs carry through, such as repeated domes, this time topped with crosses instead of crescents. The use of colour tinting to differentiate the scenes also helps each tale have a distinctive feel. The cinematography of Helmar Lerski capitalises on the play of light, shadow, and drifting smoke to give this vignette a very painterly texture. The results are darkly beautiful and delightfully disturbing.

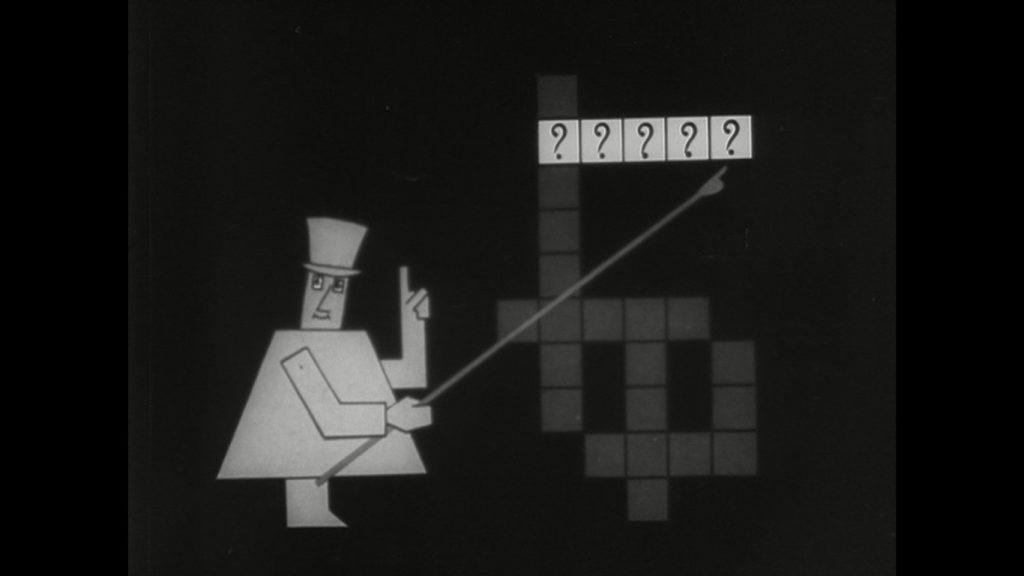

The final tale is hardly a story at all. In the opening scenes we were promised Spring-heeled Jack, one of the most intriguing folkloric characters from Victorian England, a mystery madman who terrorised the streets and escaped by taking impossible leaps over roofs and rivers—as if he had springs attached to his heels, hence his moniker. What we get is the figure of Jack the Ripper, stalking the poet and his beloved with glinting blade at the ready. I guess the two Jacks have merged in the German imagination, but I was a little disappointed. After all, Jack the Ripper, or his clones, show op all too often in numerous horror movies… but can you think of a film featuring Spring-heeled Jack?

This fragment may not be a great story, but that’s okay because its framed as a dream sequence and the cinematography was startlingly inventive at the time. Echoing the brief opening scenes, the denouement overlays multiple exposures of slanting sets as the translucent couple try to elude the seemingly relentless approach of Jack, dressed in long, dark overcoat, hat and scarf, his darkness giving him more substance than the shadows he slips through.

There was to be another story in the original script written by Henrik Galeen, who’d been writing strong and silent expressionist films since he collaborated with Paul Wegener as co-writer and co-director of the first version of The Golem (1915). He also adapted the story of Dracula for Murnau’s Nosferatu. The missing tale would’ve been about Rinaldo Rinaldini, a romanticised robber baron in the mould of Robin Hood or perhaps Dick Turpin. We glimpsed his wax figure at the beginning, but the constraints of schedule and budget curtailed the production. Though I’d love to see that story, I was more than satisfied with the serving as is.

It’s a miracle we get to see any of it at all. The reconstruction presented here is the result of international cooperation and the skillful splicing of several different prints and surviving fragments. Resolution and colour values were smoothed out and digitally matched to blend as seamlessly as possible. Yes, there are few times where one can ‘see the joins’, but unless a full, pristine original print ever comes up, this is as good as it gets!

The film also served its makers well enough as a ‘showreel’ to help its director and some of its stars to escape Nazi oppression and transition successfully to Hollywood. Paul Leni would export the Expressionist style to America and showcase its distinctively dramatic sets and dark shadows in The Cat and the Canary (1927).

With The Man Who Laughs he’d go on to establish the Expressionist style as a template for what would define the horror genre in the look of Universal’s classic monster movies that dominated the studio’s output through the 1930s. He once again called upon the talents of Conrad Veidt for the lead in The Man Who Laughs, setting him up for a long career.

Hollywood also suited William Dieterle where he became a prolific director himself. Ironically, both Veidt and Dietele would have longer careers than Leni who died too early, in 1929, from an infected tooth abscess. Sad, but he left us such a notable legacy… one that’s ripe for reappraisal.

GERMANY | 1924 | 107 MINUTES (ORIGINAL) • 82 MINUTES (RESTORED) | 1.33:1 | BLACK & WHITE | GERMAN (SILENT)

directors: Paul Leni & Leo Birinski (2nd Unit & Producer).

writer: Henrik Galeen.

starring: Emil Jannings, Conrad Veidt, Werner Krauss & William Dieterle.