THE MAN WHO LAUGHS (1928)

When a proud noble refuses to kiss the hand of the despotic King James in 1690, he is cruelly executed and his son surgically disfigured.

When a proud noble refuses to kiss the hand of the despotic King James in 1690, he is cruelly executed and his son surgically disfigured.

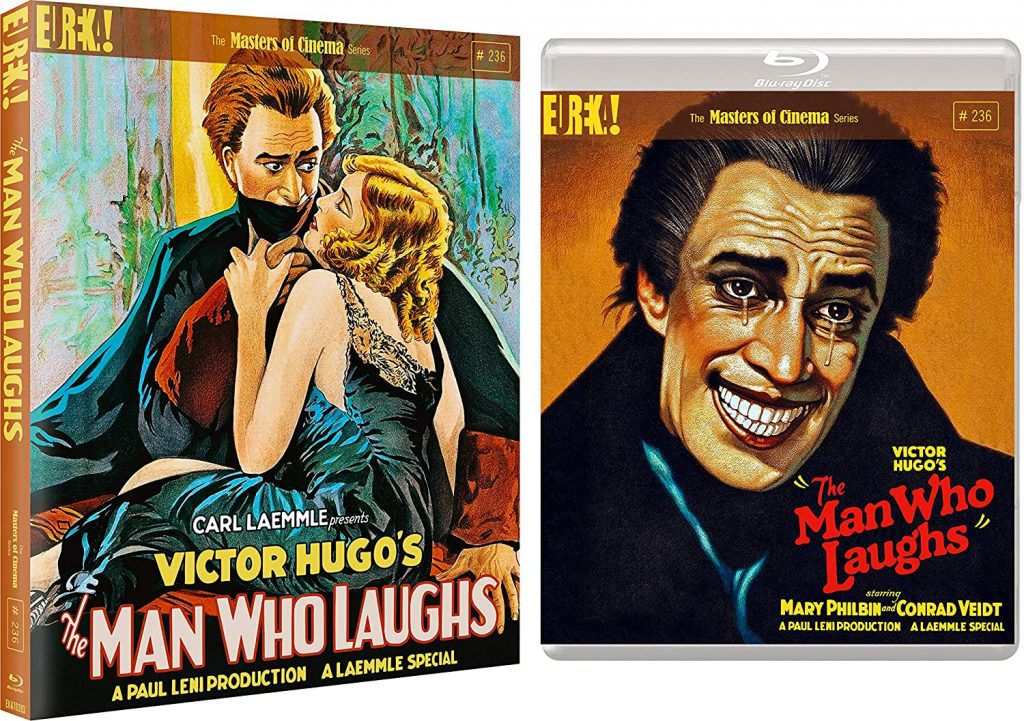

Finally, thanks to this superlative restoration on Blu-ray as part of Eureka Entertainment’s ‘Masters of Cinema’ collection, I get to see Paul Leni’s The Man Who Laughs. For a long time, all I knew about several classic silent films were snatches of their imagery. Some of my favourite film stills are from the silent age and a select few hang framed over my desk.

Many of these tantalising glimpses are from lost films or ones that were too decayed to be released. But, since the turn of the millennium, digital technologies have improved exponentially and it’s now possible for some of these rare movies to be rescued, restored, even reconstructed, and re-released. It’s always with a little trepidation that I seek them out, though, because sometimes they don’t live up to the expectations stoked by years of seeing those isolated images.

One of the almost legendary silent movies I knew well, but only from photos, long before I saw it was The Cabinet of Dr Caligari (1920). It turned out to be pretty much what I was hoping for, with its distinctively distorted sets and a mesmeric performance from Conrad Veidt as Cesare, Caligari’s mesmerised somnambulist. Then there was that other masterpiece of German Expressionist cinema, The Golem (1920), thought to have been destroyed in a fire but, eventually, a later extended print was reassembled and restored for release by Eureka just last year. Wonderful!

Possibly my favourite of all film frames is the Masque of the Red Death scene from The Phantom of the Opera (1925). Y’know, when Lon Chaney descends the grand staircase in that ostentatiously plumed hat, skull mask and with a skull-topped staff? (It’s my costume of choice for Halloween parties!) When I got to see the movie, I certainly wasn’t let down. It’s a work of art, boasting the iconic Paris Opera House set and Lon Chaney’s best performance at its heart, which remains one of the greatest of the silent age.

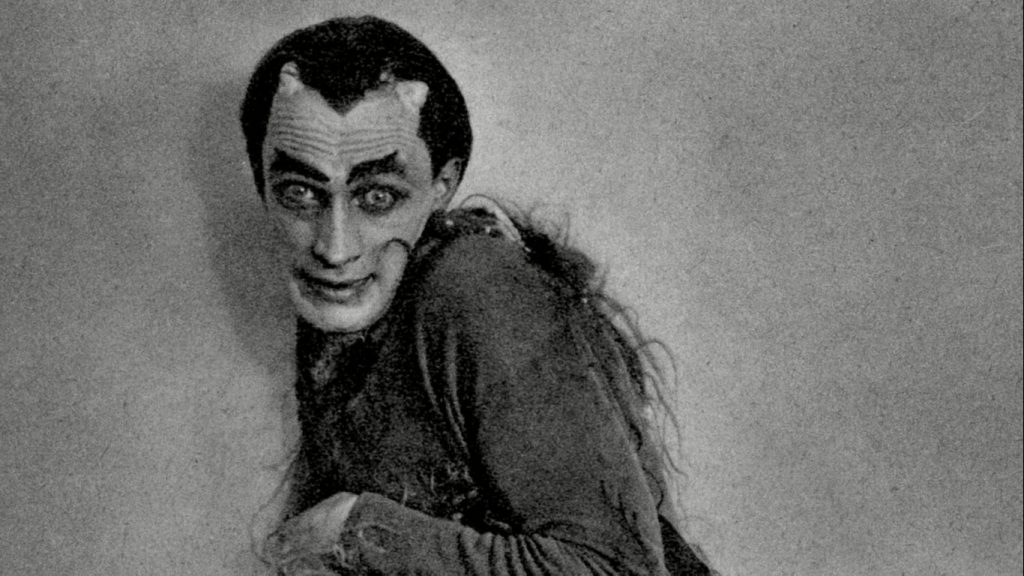

It’s now well-known that a single image, along with just an inkling of the plot from The Man Who Laughs, inspired the creators of Batman (Bob Kane and Bill Finger) when they came up with his nemesis. There’s a striking image of Conrad Veidt in his rictus grin make-up for the film that appeared in many books about the early days of horror cinema. Kane freely admits that, without having seen the film, he lifted that particular image for his first concept sketches of the Joker. I wonder if he knew the film’s arch-villain was also an unfunny ‘joker’, an evil court jester, and the man with the impossible grin in that publicity shot was the protagonist.

For the maverick producer and founder of Universal Studios, Carl Laemmle, The Man Who Laughs completed an informal trilogy of stories adapted from great French novels. The Hunchback of Notre Dame (1923), from the 1831 grand Gothic novel by Victor Hugo, was one of the earliest films to show that big budgets could pay big dividends. It cost around $1.8M, which was colossal for the time, and it earned back $3.1M. It remains Universal’s most successful silent film.

Laemmle knew the film owed its success, in no small part, to the towering talent of its star and co-director, Lon Chaney. So he immediately looked for another vehicle of similar potential to suit ‘The Man of a Thousand Faces’. He returned to the Romantic literature of Victor Hugo for his source material and settled on The Man Who Laughs, a lesser-known historical novel written in 1869.

He failed to secure the rights to the story and instead embarked on production for The Phantom of the Opera based on the 1910 Gothic horror novel by Gaston Leroux. The second of the French classics trilogy became another box office hit, so Laemmle was eager to exploit this successful formula further and, by then, could afford to get The Man Who Laughs back on track…

Set against the tumultuous backdrop of Stuart era England, it’s a politically-charged allegory written by Hugo while he was in exile due to his overtly socialist views that opposed the Napoleonic regime in France. No doubt Laemmle saw strong parallels with the changing politics of contemporary Germany as their short-lived, post-war republic was being dismantled and tensions were building that would inevitably lead them to a second war.

The story has a humanist core and champions democracy of the people over hereditary hierarchies. It was adapted by writers from the Universal stable, overseen by J. Grubb Alexander, and while faithfully preserving the central plot and historical setting, moderates its political message. Thankfully, it also neglects to include the novel’s unbearably tragic ending.

Approached as a sequel of sorts for The Phantom of the Opera, which was also about a disfigured character, it was expected to star Lon Chaney with Mary Philbin again. By then, Chaney was box office gold and had been sold-off to MGM… but, despite this, Laemmle managed to negotiate a contract that freed him up for the part. As the production was in development, it was Chaney who caused consternation and withdrew, leaving Laemmle in the lurch. Who else could possibly pull off the role?

Without the presence of Chaney, Laemmle knew he needed an assured director at the helm. After Paul Leni’s first two films for Universal, the stylistically bold, darkly comic horror The Cat and the Canary (1927), and The Chinese Parrot (1927), a Charlie Chan mystery, Laemmle was confident he’d be perfect for the job.

Paul Leni had a proven track record long before his move to Hollywood. After working as a theatrical set designer and in the art departments for numerous German productions, his first proper film as director was Prima Vera (1917), made a decade earlier.

He’d come to the attention of Hollywood with Das Wachsfigurenkabinett / Waxworks (1924), an inventive horror portmanteau of three linked stories with the distinctive stylings of German Expressionist cinema. It starred Conrad Veidt as Ivan the Terrible and Leni knew the versatile Veidt was maybe the only actor who could step into Chaney’s shoes.

Conrad Veidt was to prove him right with his bravura performance as Gwynplaine, though we first see him as Lord Clancharlie, one of the rebel Lords who refused to acknowledge the rule of King James II (Sam De Grasse). He has returned to plead for the life of his young son who’s being held captive in a ploy to entrap Clancharlie.

It’s Barkilphedro (Brandon Hurst), the king’s jester and scheming confidant, who suggests he spare the boy’s life, but only after he’s had him disfigured by mad surgeons so he will be forever laughing at his father’s failure and humiliating execution in the Iron Maiden.

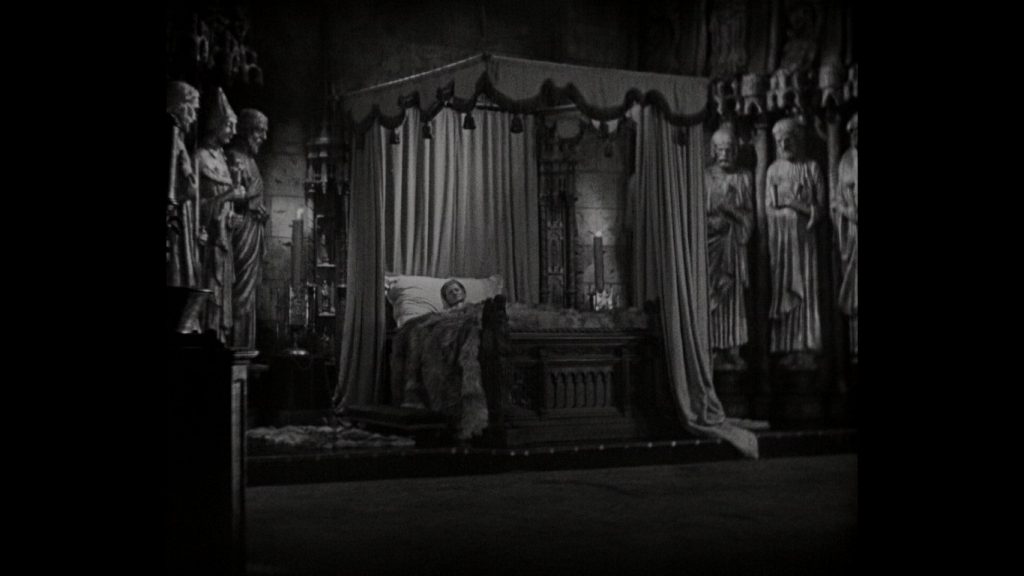

Paul Leni’s flair for costume and décor are evident throughout this opening sequence. The walls of the King’s chambers are lined with sternly oppressive gothic statuary recycled from the cathedral façade of the Hunchback of Notre Dame set. Quite literally a dismantled face. The textures of torn lace and soiled velvet textures in Clancharlie’s costume are absolutely exquisite, and truly showcase the extent and quality of this 4K restoration too!

Barkilphedro’s evil jester costume and fool’s cap with flaccid waist-length jingling horns is certainly in keeping with an expressionist aesthetic, and Brandon Hurst sure makes the most of it. He’s an excellent physical actor, well-suited to silent media, and was already known to audiences as the villainous and similarly manipulative Jehan in The Hunchback of Notre Dame.

Here, he navigates a sick balance of malice and mirthless irony in every attenuated gesture and obsequious grin. We can tell, at a glance, that he’s the true villain of the piece. Even so, we don’t yet realise that suggesting the mutilation of a child is just the entrée as far as his machinations of cruelty will go.

What they do to the young Gwynplaine, though suitably shocking, is considerably toned-down compared to what’s described in Hugo’s book and is kept from us as we watch, from the child’s eye-level point of view, as the iron maiden closes upon his father. The stark horror of the act isolated against featureless black, because there is nothing else to see—that was his whole world, destroyed.

The toddler is then handed over to the ‘surgeon’ who mutilated him and at the same time, he and all his Comprachico compatriots are exiled under pain of death by royal decree. It seems the Comprachicos are a racist invention of Victor Hugo. They’re a fictitious clan of gipsy-like ‘child-stealers’ who reputedly took-in young orphans and then, through various surgical and chemical techniques, mutilated their features, and stunted their growth.

They are described as practising “the antithesis of orthopaedy” to manufacture freaks for the entertainment of noble courts or to be sold to circus sideshows. There’s scant historical evidence for such a trade. It’s referenced in medieval literature, including Shakespeare, though thought to have died out by the time this story takes place, in the 17th-century. Still, child-stealers are a mainstay of folklore and the stuff of nightmares.

We only get to see young Gwynplaine (Julius Molnar) when he’s abandoned by the Comprachicos as they set sail, leaving him to die on the shore in a dramatic snowstorm. He wanders alone past the rotting corpses of Comprachicos who have been caught and summarily hanged on high gibbets.

This a starkly haunting image of a small figure alone in a vast unforgiving landscape, was achieved by the ingenious use of miniatures by effects genius Charles D. Hall who had already worked on The Phantom of the Opera and with Leni on The Cat and the Canary. He would go on to contribute to many major productions, such as Show Boat (1929) and All Quiet on the Western Front (1930), but is best known in cult circles for his magnificent work on Tod Browning’s Dracula (1931) and James Wale’s Frankenstein (1931).

Just when Gwynplaine is losing all hope he comes across the corpse of a dead mother still cradling her baby. He seems ready to lie down and join the almost saintly tableau when he feels that the baby is still warm. This spurs him on for a little longer as he tries to find help and saving the baby will also symbolise his rebirth into a new life. He finds refuge with the curmudgeonly yet kind Ursus (Cesare Gravina), a travelling tinker and entertainer, who is obviously poor yet prepared to share his meagre rations with the disfigured young boy and the baby girl he declares is blind…

… and all that happens in just the first 15 of its 110-minute duration!

It’s no wonder contemporary critics and reviewers alike complained that it was too dark and morbid to be called entertainment. I’ll admit the imagery of that opening sequence is incredibly intense and draws heavily from Leni’s deep roots in the cinema of German Expressionism, which pioneered what we would recognise today as the horror genre. In the 1920s this was a relatively new vibe for Hollywood and Carl Laemmle’s French classics trilogy ushered in the golden age of Hollywood horror which would be dominated by Universal for the next decade.

After the backstory has been established with impressive economy, the film becomes far more beautiful than bleak. We flash forward to the grown-up Gwynplaine (Conrad Veidt), who’s been lovingly raised by Ursus, along with the beautiful girl whose life he saved, Dea (Mary Philbin). They’re now the star act in a travelling troupe of clowns and players.

Gwynplaine is a clown billed as ‘The Laughing Man’ and Dea acts and sings opposite him. An unspoken love has grown between them, but Gwynplaine feels he cannot declare it and believes she only cares for him because, being blind, she doesn’t know what he looks like. What seemed to be a horror film suddenly becomes a bitter sweet gothic romance with unexpected depth and sensitivity.

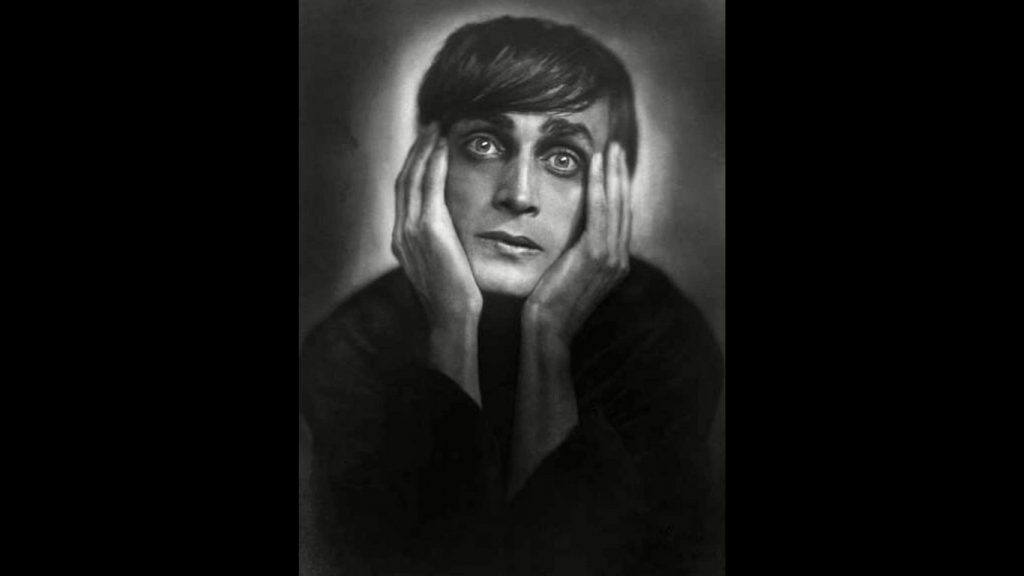

Conrad Veidt’s performance is a revelation. Even though the lower half of his face is all but immobilised, he manages to do more than enough with his eyes. Combine this with his physical presence and talent with mime and he conveys a greater depth of emotion than many an actor does with their full set of physical faculties. He also uses his expressive hands to great effect, speaking volumes with how they touch Dea’s hair, or apply his white-face clown makeup, or close the doors over his dressing room mirror.

To add to the mystique of Veidt and the character, the makeup artist was not credited at the time. The fixed rictus grin of Gwynplaine was created by Jack P. Pierce by inserting a false palate and enlarged teeth over Veidt’s own. This isn’t dissimilar to the tricks devised by Lon Chaney, who famously always did his own makeup effects. Wires then looped from this insert and hooked into the corners of Veidt’s mouth, stretching them painfully into the extreme, nearly immobile grin. Perhaps that inner agony we see in his wonderfully expressive eyes is actually just, well, straightforward pain.

Pierce became a pioneer of Hollywood horror makeup working on most of the Universal classics. He repeatedly worked with directors Tod Browning and James Whale and was responsible for Dracula, Frankenstein and his Bride, The Invisible Man (that’s not as easy as it sounds), The Mummy and a couple of Wolfmen…

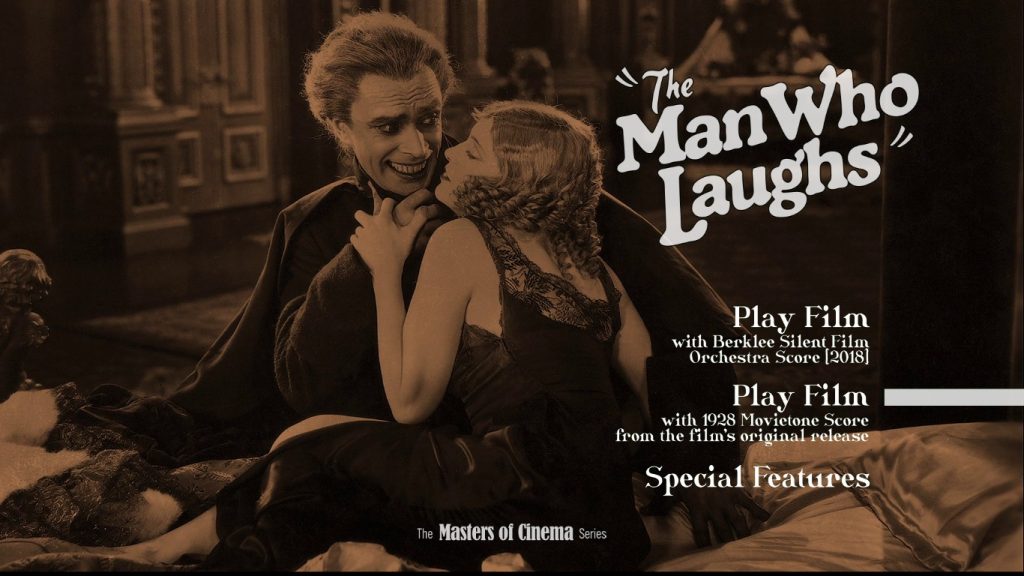

Fate takes an unexpected turn when Duchess Josiana (Olga Baclanova) a noblewoman in the court of Queen Anne (Josephine Crowell), anonymously sneaks in to watch their show. She’s a scheming and amoral tear-away but something inside her is profoundly affected by Gwynplaine’s performance. She finds his monstrous appearance thrilling, possessing a terrible form of beauty that she feels reflects her inner self.

Leni makes much of reflections and outward appearances. He explores the idea of how we choose to see ourselves in contrast with how others might. We often watch Gwynplaine’s face reflected in a mirror while he talks with Dea and we can see what he doesn’t—that she clearly reflects his love. This is possibly Philbin’s best performance. I haven’t seen them all, but her adequate performance opposite Chaney in Phantom is not as electrified as when she shares the screen with Veidt.

Having said that, many of the subtleties of all the performances here may be lost to a modern audience unused to the grammar of silent movies. I find it helps to let go of your preconceptions of cinema and think of such films as performed graphic novels. Indeed, the silent film is similarly a purely visual medium. The beautifully composed shots and painterly uses of chiaroscuro would work just as well as the best frames from any respected comic-book.

Lusty Josiana invites Gwynplaine to come and visit her at the palace and this confuses his emotional state further. Here’s a desirable woman, known for her many suitors, who’s seen him and yet still finds him attractive. One just knows his past would catch up with him at some point and offer a shot of revenge in ‘Count of Monte Cristo’ style… and, at this point, just when things were beginning to drag a little, that narrative starts to kick-in, complicating things considerably.

For the second half of the story, I don’t think any character arc follows a perfectly smooth trajectory. They all do unexpected things and their behaviours are often surprising, yet totally congruent. Maybe the unusual depth of the central characters, at a time when cinema was all about stereotypes and shorthand, is derived from the richness of the literary source material.#

I’ll give no more away, except we recognise Josiana’s menacing man servant, even though he’s no longer wearing his evil jester guise. At least to begin with, he’s the only character with knowledge of who Gwynplaine really is. Barkilphedro’s such a great, genuinely nasty, villain that you’re dying for him to get his comeuppance for the remainder of the movie. Question is, does he?

It builds to a genuinely ‘edge of the seat’ and fully satisfying finale. There’s some swashbuckling style action with sword fights on castle ramparts. Epic scenes involving hundreds of extras in the streets of a town that looks more like an expressionistic Bavaria than 17th-century England. The large, theatrical sets are impressive throughout. There are even villagers with torches and what is one of the best, though fleetingly brief, cinematic moments involving a dog.

I went into The Man Who Laughs in the hope of finding another silent film that may aim at a similar level of sublime beauty as The Phantom of the Opera. I mean, I knew there couldn’t be another performance to touch the heights of horror and depths of pathos like Chaney’s Erik did. I see now that I was wrong!

On many levels, The Man Who Laughs is an even better movie. Certainly, the motivations that drive the characters are more unusual and intriguing. I urge any fans of Hollywood’s silent age to give it a viewing. Even if you’re not one for the silents, this wouldn’t be a bad place to start. Though it would then set the bar rather high.

Perhaps unsurprisingly, it didn’t do well when it was initially released during a time of great upheaval in cinema. Its budget was estimated at around $1M dollars and it struggled to claw back just $30,000… as the new ‘talkies’ were suddenly all the rage. It’s all the audiences were talking about! Although The Man Who Laughs was completed and ready to go in 1927, it was held back a year to have a synchronised soundtrack added, mainly from Movietone’s stock sound effects.

It really doesn’t work when you hear music, drums, and crowds cheering but, when the central characters say anything, they make no sound. Even the addition of a popular song, “When Love Comes Stealing”, couldn’t save it. But its fate was probably sealed by some stiff competition.

It was vying for attention next to Laugh, Clown, Laugh (1928) another silent sinister clown story, but starring Lon Chaney and Loretta Young. Also, The Singing Fool (1928), a follow-up to The Jazz Singer (1927) and again starring Al Jolson, was released around the same time. It was the first full-length movie with a synchronised soundtrack that included sequences of dialogue and plenty of music and singing. It broke all box office records at the time and remained the most financially successful film for nearly a decade until Disney set a new record with Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs (1937). The Man Who Laughs didn’t really stand a chance and sank into comparative obscurity.

Like The Phantom of the Opera, the story has been remade several times since. My favourite remake being Sergio Corbucci’s wonderfully camp swashbuckling romp of 1966, which transposed the action to Italy under the Borgias and made up for what it lacked in budget with exuberance and vivid colour saturation. I’ve not seen the 2014 remake with Gérard Depardieu as the fatherly Ursus and Marc-André Grondin as Gwynplaine, but judging from the trailer, not much effort was put into the grinning makeup and the result is nowhere as impressive, or affecting…

Leni is often cited as the single most important influence upon horror cinema albeit translated through the work of other, more famous pioneers of the genre. The Man Who Laughs was a direct inspiration for Tod Browning, most evidently in his infamous, once banned movie, Freaks (1932). Leni’s earlier film, The Cat and the Canary, can be seen resounding through the work of James Whale, perhaps most clearly in The Old Dark House (1932).

All the great Universal horror films of the 1930s owe a great stylistic debt and, decades later, makeup artists Randall William Cook tried to emulate the look of Veidt’s Gwynplaine, merged with Chaney’s Phantom, for his own role as Dr Kessler in I, Madman (1989).

Sadly, Paul Leni, who’d proved himself to be a director with huge potential only made one more film, The Last Warning (1928), a murder-mystery with horror undertones. He died the following year, age 44, due to sepsis arising from an untreated tooth abscess.

USA | 1928 | 110 MINUTES | 1.20:1 | BLACK & WHITE | ENGLISH

director: Paul Leni.

writers: J. Grubb Alexander, Walter Anthony, Mary McLean & Charles E. Whittaker (based on the book by Victor Hugo)

starring: Mary Philbin, Conrad Veidt, Brandon Hurst, Olga V. Baklanova, Cesare Gravina, Stuart Holmes, Samuel de Grasse, George Siegmann & Josephine Crowell.