SUNSET BOULEVARD (1950)

A screenwriter develops a dangerous relationship with a faded film star determined to make a triumphant return.

A screenwriter develops a dangerous relationship with a faded film star determined to make a triumphant return.

Gloria Swanson’s Norma Desmond is ever-present in Sunset Boulevard, even in scenes where she doesn’t appear! Other characters discuss her, and the audience worries what she might think if she knew what’s being kept from her. And, of course, that’s the historical irony of Billy Wilder’s 1950 classic: this film about a woman longing to regain her lost stardom itself made the character a star, and perhaps also brought back into public awareness the many gods and goddesses of the silent screen who had, as co-writer Charles Brackett put it, been “brushed into obscurity” by the coming of sound.

Indeed, Brackett and director/co-writer Billy Wilder conceived of Norma before anything else in Sunset Boulevard. The author Sam Staggs suggests that Wilder may have hit upon the character after witnessing an embittered outburst from D.W Griffith, the mighty silent director who never made it in talkies. But in any case, although Sunset Boulevard’s final shape was uncertain even while it was being shot, and at one stage this bleak noir was (amazingly) conceived of as a comedy, Norma was a constant.

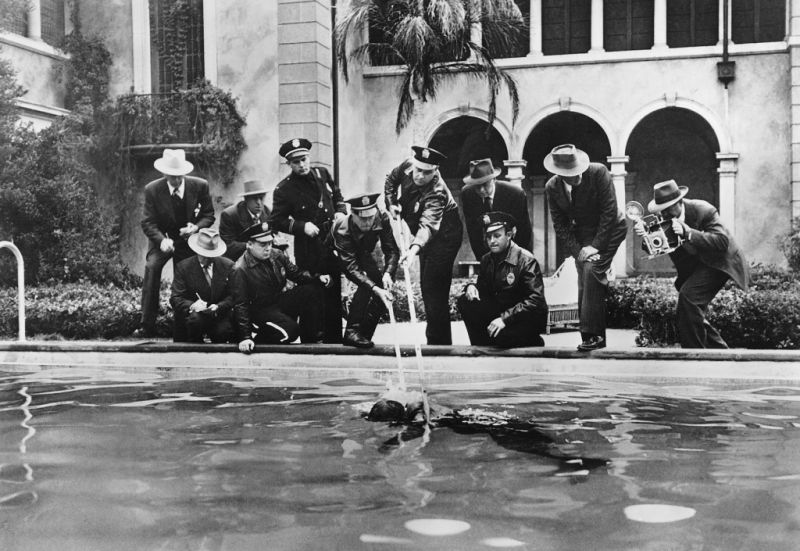

The film doesn’t start with her, though. It starts with Joe Gillis (William Holden) floating dead in a swimming pool, and with voiceover narration—hardboiled and perceptive—that we soon realise is his. Almost the entire movie, save for the final few minutes, will be told as a flashback leading up to this point, and the narration continues throughout.

The story proper begins with Joe (a not-very-successful young screenwriter who’s left Ohio for Hollywood) failing to sell a script to Paramount (the studio which made Sunset Boulevard and which features prominently therein), then being visited by a pair of repo men who want to take away his car. Evading them, he plans to hide it at an apparently deserted mansion on Sunset Boulevard.

But the mansion turns out to be inhabited by the fading silent movie star Norma (Swanson) and her manservant Max (Erich von Stroheim)… and so, after a non-stop and completely absorbing whirl around Joe’s unsettled life, we now meet the woman and the place who will dominate the rest of the film as Joe becomes script doctor for Norma’s dreamed-of comeback movie, then her reluctant but perhaps inevitable toy boy.

Joe never really likes Norma, though his posthumous narration does display a little sympathy for her at the very end. Norma, for her part, seems hardly aware of anyone else existing at all, except insofar as they reflect on her. So they are not so much an odd couple as a clearly doomed one, their initial mutual antipathy never fully overcome. And their conflicting realities are evident from their first encounter, where (in one of Sunset Boulevard’s most famous exchanges) Joe says “you used to be big” and Norma replies “I am big. It’s the pictures that got small.”

It’s this that gives Sunset Boulevard its pervasive air of desperation and its strong sense of noir, despite having a much grander milieu than most. Both Joe and Norma are failing, in their different ways; both see the other as a potential solution, not a person. Perhaps Joe’s exploitation of Norma is more self-aware than hers of him, for he realises that Cecil B. DeMille is never going to direct her terrible script of Salome, and perhaps his self-loathing is more conscious as a result, but in any case neither is a likeable character.

Yet neither is truly wicked, and even if Sunset Boulevard is often as overwrought as the silent movie that Norma screens in her mansion (actually the real Swanson vehicle Queen Kelly) it’s more humanly subtle than it might seem at first glance. Joe and Norma are both victims in this “story of how Hollywood makes promises it doesn’t keep”, as actress Nancy Olson—who plays Betty, Joe’s more genuine love interest—put it in an interview.

Subtlety is not always Sunset Boulevard’s strongest point, however, perhaps because audiences of the 1950s needed themes brought out. The screenplay by Brackett and Wilder hammers home the idea of Norma’s obsolescence, often using her car or house as a metaphor. Joe calls the mansion “a white elephant”, “the kind crazy movie people built in the crazy ’20s”. He compares it to Dickens’s Miss Havisham and describes “the ghost of a tennis court… with faded markings and a sagging net”. The references clearly are not really to the house itself, but to Norma.

Similarly, his dream of “a chimp dancing for pennies” (presumably his view of himself) is dime-store Freudianism, and the whole movie indeed hangs on a not-quite-plausible coincidence (Norma happens to be awaiting delivery of a coffin for her dead chimp at the exact moment Joe turns up).

But there are countless much less heavy-handed touches from Brackett and Wilder. The image of the man shot in the swimming pool must be harking back to Fitzgerald’s Great Gatsby, referencing another American Dream gone wrong. Norma’s comment that “I don’t want to be left alone” is a clever inversion of Greta Garbo’s most famous statement. And in a movie that reveals something new every time you see it, even seemingly throwaway lines can be telling. For example, when Norma visits DeMille (playing himself) on the Paramount lot and he tells his set technicians to “turn that light back where it belongs”, the unspoken meaning is that the spotlight no longer belongs on Norma.

There are some great non-Norma moments, too, notably the brief exchange in a clothing store where a comment from the clerk prompts Joe to defiantly deny that he’s a kept man and the wonderful scene where Joe and Betty (whose character is also an aspiring screenwriter) flirt in improvised, super-clichéd Hollywood dialogue. Like much of Sunset Boulevard, this is unusually meta for the period. And again, as in much of the movie, though Norma’s not there, the scene implicitly alludes to her. Joe and Betty are blurring the movies and their real lives in exactly the way that Norma does.

Less overt, but also undoubtedly contributing much to Sunset Boulevard’s enveloping atmosphere, is the faint air of the supernatural. (Indeed, the original cut began with a voiceover conversation among ghosts, including Joe’s, but that was dropped after preview audiences laughed at it.) It’s never quite explained how von Stroheim’s Max could’ve made up a bed for Joe in Norma’s house before he knew that Joe would come by, for example. And the shot when Norma pulls Joe toward her for a first kiss, stretching out a bony hand on New Year’s Eve just as Auld Lang Syne concludes, could almost come from a vampire tale. It would be wrong to assume that Wilder and Brackett truly intended us to imagine anything paranormal, but the spookiness adds a further layer of unreality to life in Norma’s mansions.

More than any of this, though, Swanson’s Norma remains the most-remembered thing from Sunset Boulevard, playing the silent movie queen in melodramatic silent style, and only letting us fully see her madness at the very close; up until then she has always seemed at least partially in touch with reality. Swanson also reportedly did much to shape the character, insisting that Norma be softened and made less monstrous, something that was probably achieved through the portrayal of a vulnerable side in her scene with DeMille on the Paramount lot.

Even if the other leads never have her presence—and it would have been a misjudgement if they had—they do, nevertheless, contribute much. Most memorable, perhaps, is von Stroheim’s manservant, initially seeming threatening but eventually emerging as the only truly decent person in the mansion, his facial expressions more restrained than Swanson’s but equally revealing.

Holden is blander, and the film might have been an even more interesting one with the original choice of Montgomery Clift taking the part of Joe; though Clift was only slightly younger than Holden, he looked a lot younger, and his casting would have heightened the (then) shocking nature of Norma and Joe’s sexual relationship.

Still, Holden does a nice line in world-weariness and moral decay, his performance as a hack who can’t quite make it in Hollywood perhaps informed by the doldrums his own career had lately been in (Sunset Boulevard returned him to the limelight). Olson, meanwhile, thoroughly deserved her Academy Award nomination, investing Nancy with just the right balance of energetic enthusiasm and emergent youthful cynicism.

The cast of Sunset Boulevard is noteworthy, too, for the Hollywood names playing themselves: not just DeMille, but also Buster Keaton, legendary gossip columnist Hedda Hopper, and others. They’re human equivalents of the Hollywood locations like the Paramount studio and Schwab’s Pharmacy which add such verisimilitude to the film.

Yet the biggest star of Sunset Boulevard (after Swanson/Desmond, of course) is the writing team of Brackett and Wilder, whose last collaboration it would be. They had worked together on a string of well-regarded movies such as Ninotchka (1939) and The Lost Weekend (1945), the latter—rather like Wilder’s 1944 Double Indemnity, which he co-wrote with Raymond Chandler—as dark and daring as Sunset Boulevard. And although today we tend to think of Sunset Boulevard as a Wilder film, credit should really go to him and Brackett jointly, so extensive was Brackett’s part in building the movie we know. (D.M Marshman also contributed to the script.)

Wilder was unusual as a director in being primarily interested in the words, less so in the visuals. Even so, Sunset Boulevard works well enough in directorial terms, and the way that Norma’s house and the outside world are contrasted is effective (we never quite get the sense that Joe is trapped in the house, or quite feel that he’s free when beyond its walls; both possibilities are tantalisingly close, though). But, like the fine score from Wilder’s friend Franz Waxman, the direction and photography are inobtrusive supporters of the mood created by screenplay and performances, not principal contributors to it.

Sunset Boulevard was not a huge hit with audiences, but critics were mostly quick to see its qualities, identifying early on the characteristics that have established it as a major classic of the period. Among the most astute observations was that of The Christian Century’s reviewer: “Morbid characterizations of unadmirable people make this a most unpleasant but very effective film.” James Agee, writing in Sight & Sound, considered it “much the most ambitious movie about Hollywood ever done” (and it was perhaps the most honest up to that time in destroying illusions too), yet he was also right to comment that it’s a rather cold film as well. At the Academy Awards, Sunset Boulevard won only for its screenplay, score, and art direction, although it almost certainly would’ve garnered more Oscars had it not been up against Joseph L. Mankiewicz’s All About Eve.

There has been no remake or sequel (though a movie of Norma’s trial might have its own over-the-top appeal…), yet Sunset Boulevard’s strong influence continues to be felt. The Andrew Lloyd Webber musical of the same name is the most directly linked work, but it’s impossible to avoid echoesin many places: in the aged, deranged actress of Whatever Happened to Baby Jane? (1962) and the Henry Farrell novel on which it is based, for instance.

Then there’s Midnight in the Garden of Good and Evil (1997), where the piano played at a jolly party is contrasted with the pipe organ in Kevin Spacey’s mansion just as the piano at a New Year’s Eve shindig to which Joe escapes is opposed to the lugubrious organ in Norma’s home.

There’s David Lynch’s Mulholland Drive (2001), surely referring to Sunset Boulevard in its title and more generally in its world of nightmare, decay, and broken Hollywood dreams. Or AMC’s Mad Men, where it’s easy to imagine that the character of Peggy Olson could be partly based on Nancy Olson’s Betty.

But Sunset Boulevard’s biggest legacy is, of course, Norma: a character realised so vividly and indelibly by Swanson that it is hard not to believe her real. She’s familiar, as a type if not a name, even to those who haven’t seen the film. And so it’s fitting that (in a film full of such meta comment on film) her deluded, self-flattering declaration during Sunset Boulevard’s unforgettable finale (“Mr. DeMille, I’m ready for my close-up”) as she is being led toward the waiting patrol cars and presumably a life in jail or a mental institution—turned out, in its own way, to be quite accurate.

For Norma Desmond, after all, the last 70 years since Sunset Boulevard have been one long, mythologising close-up.

USA | 1950 | 110 MINUTES | 1.37:1 | BLACK & WHITE | ENGLISH

director: Billy Wilder.

writers: Charles Brackett, Billy Wilder & D.M Marshman Jr.

starring: William Holden, Gloria Swanson, Erich von Stroheim, Nancy Olson, Fred Clark & Lloyd Gough.