MAJOR DUNDEE (1965)

Towards the end of the American Civil War, a Union officer assembles a motley force to cross into Mexico and defeat the Apache

Towards the end of the American Civil War, a Union officer assembles a motley force to cross into Mexico and defeat the Apache

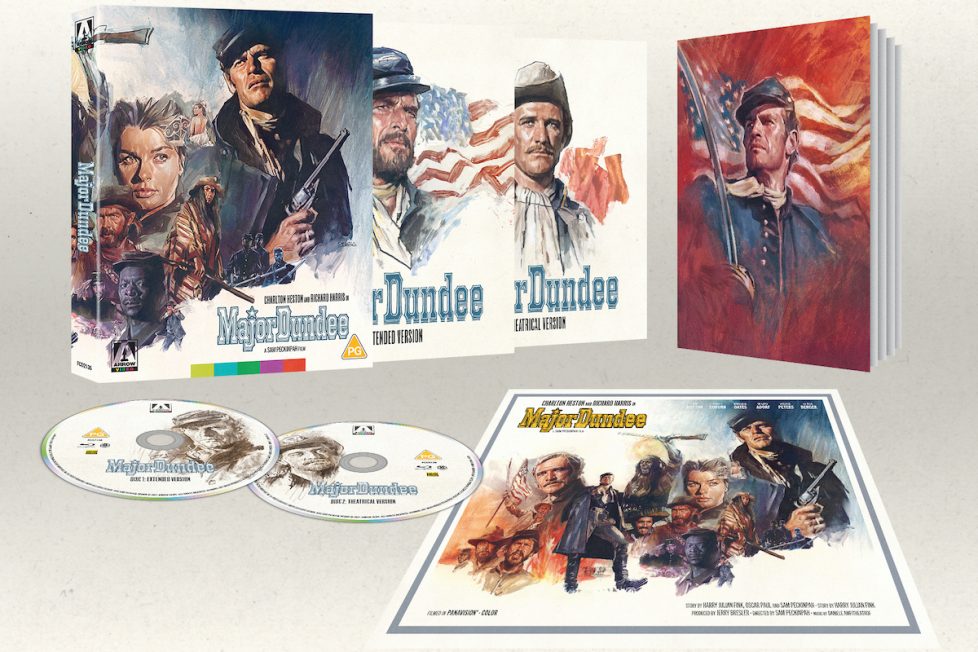

Described by the historian of western films, Jim Kitses, as “one of Hollywood’s great broken monuments”, Sam Peckinpah’s Major Dundee is probably still more famous for the messiness of its production than its merits as a movie. But if the original cut of 1965 is deeply unsatisfactory, the restored version premiered in 2005 (now re-released by Arrow in a lavish two-disc set with a panoply of extras), works perfectly well as a film in its own right, despite a few flaws, and offers a glimpse of what Peckinpah was aiming for.

Although he was already a successful director of televisions westerns with The Westerner (1960) and Gunsmoke (1955-1975), and had made two theatrical features including the well-received Ride the High Country (1962), Peckinpah wasn’t the first choice for Major Dundee. Producer Jerry Bresler and leading man Charlton Heston (who had long wanted to do a Civil War movie) had already decided to film Harry Julian Fink’s screenplay, but first-choice director John Ford was busy making Cheyenne Autumn (1964). Heston approved Peckinpah as an alternative, and once he was on board he reworked Fink’s unwieldy and over-long script with co-writer Oscar Saul.

Tensions between Peckinpah and Columbia Pictures began early, however, with disagreements over personnel choices and a then-huge last-minute budget cut from $4.5M to $3M. (Despite this, Peckinpah went and spent $4.5M anyway—roughly $40M in today’s money, enough to make 2019’s Knives Out. When the movie finally reached cinemas, such was its reputation for excess that The New York Times headlined its review ‘Costly Western Opens at Capitol Theater‘.) Filming itself was chaotic, with Peckinpah frequently drunk, considered out of control by the studio, and nearly fired.

The finished product was also far too long. Major Dundee had originally been envisaged as an epic, complete with intermission, but Columbia had become more cautious and the budget cut reflected the studio’s trimmed-down ambitions. So it was heavily edited for previews, and then again for release, with the result being what Peckinpah’s biographer David Weddle described as “hopelessly fragmented and at times incoherent. Characters seemed to act without motivation, conflicts, relationships and plot points were set into motion but never brought to fruition; in its last half-hour the story collapsed like a house of cards into a jumble of arbitrary scenes.” Unsurprisingly, it was a flop, and Newsweek termed it “a disaster”.

The 2005 restoration essentially takes Major Dundee back to the preview version (except for Daniele Amfitheatrof’s music, which Peckinpah justifiably disliked and which is replaced by a far superior new score from Christopher Caliendo). So it’s not a director’s cut, as there’s still about half-an-hour of Peckinpah’s original footage missing, but it’s clearly closer to what he intended and works far better as a film. The 1965 release version is also included in Arrow’s package, for historical interest.

Taking place over a few months in 1864-65, Major Dundee is a tale of of obsession described by one of its actors, R.G. Armstrong, as “Moby-Dick on horseback.” The Civil War is nearly over and Dundee (Heston), a Union officer who apparently disgraced himself by disobeying orders at Gettysburg, has been given the ignominious assignment of supervising prisoners of war in New Mexico. He sees a chance at redemption, though, when civilians and soldiers are slaughtered in an Apache raid, and starts to assemble a ragbag force including criminals and former Confederate troops—amongst them his onetime pal and now enemy Ben Tyreen (Richard Harris).

Dundee leads this force over the border into Mexico, intending to rescue some children kidnapped by the Apaches and capture or kill their leader, Sierra Charriba. Their incursion will also bring them into conflict with the French military (at that time deployed in Mexico to fight for the emperor’s side in its own civil conflict), and inevitably there are bitter divisions within Dundee’s own force as well. For example, between former Confederate troops and black Union soldiers now finding themselves supposedly on the same side. It’s an appropriate irony that a film whose production was so riven by ill feeling derives much of its drama from a similar situation, not only among the rank and file but also between Dundee and Tyreen.

The Moby-Dick comparison is apt, to a point. Dundee is stubborn and single-minded in his pursuit of Charriba, almost to the point of self-destruction. Acting on his own initiative rather than deferring to more senior officers is exactly the thing that got him into trouble at Gettysburg, and hardly likely to redeem them in his eyes, especially when it involves an illegal crossing into Mexico and engaging the French.

However, it’s easy to suspect that what he wants to do is simply make war in general, rather than pursue Charriba in particular. As he says to the film’s love interest, Teresa (Senta Berger), “men can understand fighting. I guess maybe they need it sometimes. The truth is, it’s easy.” Perhaps he even has a death wish. Later, when Heston says “the war won’t last forever”, he’s told “it will for you, Major”. His isolation from his men, his own army, even his own Southern origins is pointed up on several occasions by medium long shots of Dundee alone.

Some of the specific interpretations of Major Dundee that have been put forth are more dubious. Superficially, the long journey of Dundee and his men deeper and deeper into Mexico (again, mirrored in the filmmaker’s own treks from one far-flung location to another), might suggest a progressive departure from the norms of civilisation, represented by the stability of their American base—much as the river journey does in Francis Ford Coppola’s Apocalypse Now (1979). And indeed, Peckinpah does make a point of displaying military discipline frequently in the American sections at the beginning of the film, but much less in the Mexican ones. On the other hand, the disagreements that fracture Dundee’s makeshift army are if anything fiercer when it is first formed, and they fight well together toward the end.

Even less tenable is the suggestion that Dundee’s questionable adventure in Mexico stands for the United States’s in southeast Asia. Simple chronology refutes this, as shooting on Major Dundee ended in April 1964, months before the Gulf of Tonkin incidents that led to the first major ramping-up of America’s involvement in Vietnam. Peckinpah’s certainly interested in what happens when military power is misapplied to a self-destructive quest, but on a personal level rather than a political one.

Quite beautiful to look at despite its cynicism, Major Dundee shows the still fairly young Peckinpah (just shy of 40 when it was made) to be a master of his craft already. Especially notable is his terrific sense for the spatial layout of scenes and shots, with depth as well as breadth, while his strong interest in the western movies of directors like Ford, Howard Hawks, and John Huston is evident in the accomplished way he puts his own twist on the standard tropes of the genre. (Peckinpah liked to hint at a Wild West childhood himself, though the reality was more staid.) Also impressive, if maybe a little too contrived, is a scene where Dundee’s forces ride out of their fort singing conflicting songs—the “Battle Hymn of the Republic” for the Union soldiers, “Dixie” for the Confederates, and “Oh My Darling, Clementine” for the civilians—which seems to pastiche a similar, straighter scene in Ford’s Fort Apache (1948). More conventional, though adroitly handled, is the final set-piece battle with the French.

Peckinpah is perhaps most famous for his movie’s violence, of course, and while Major Dundee never approaches the almost neurotic brutality of films like Straw Dogs (1971) or Bring Me the Head of Alfredo García (1974), it’s still unsparing from the opening scene depicting the aftermath of Charriba’s attack on the Americans: a blood-soaked child on the ground stuck with arrows, a tortured man hanging above a fire. Later, the sudden intrusion of another arrow into a love scene between Dundee and Teresa makes it clear where the director’s real passion lies.

An exceptionally strong cast, many of them Peckinpah regulars, helps hold together Major Dundee, which even in the restored version has some structural weaknesses. Heston, an actor of impressive gravitas in the right role, and some clunkiness when he doesn’t, here has a character that suits him every bit as much as his later part in Planet of the Apes (1968). Harris never knowingly under-acts but still captures well the pride and frustrations of Tyreen, arising not only from the Confederacy’s defeat but also from longer-standing chips on his shoulder; Dundee describes Tyreen as “a would-be cavalier, an Irish potato farmer with a plumed hat” aspiring to a Southern-gentleman ideal he will never attain.

In supporting roles, meanwhile, a taciturn James Coburn is impressive, as are Brock Peters, Armstrong, and Jim Hutton as members of Heston’s force; the latter always trying to do the correct soldierly thing and often not quite getting it, adds some welcome comic relief. Berger, meanwhile, is not as terrible as some critics suggest. The Apache warlord Charriba is played by an Australian, Michael Pate, and the Apache scout Riago by a Hispanic Mexican, José Carlos Ruiz—casting which inevitably feels dated today but works as well as it can given that.

The restored, longer version of Major Dundee corrects many of the problems that afflicted the theatrical release. For example, the fate of Riago is finally made clear, but the film still suffers from some narrative flaws. The most obvious, though charitably it could be seen as a deliberate indication of Dundee’s drive toward conflict in general, rather than the defeat of a specific opponent, is the near-disappearance of the Apaches from the storyline for a long period after the French come into play. (This makes it all the stranger that in some international markets the movie was released under the title Sierra Charriba.) The kidnapped children, the original pretext for the whole escapade, are also given short shrift, and the eventual besting of Charriba by a bugle boy is almost anti-climactic, though this too may be a deliberate de-romanticisation.

A lengthened fiesta scene becomes somewhat interminable, as well, but it’s a small price to pay for getting back so much other footage. The replacement of Amfitheatrof’s simplistic, over-dramatic score with its ludicrous closing song from Mitch Miller & The Gang is also most welcome. On one of the extras, film historian Glenn Erickson comments that it’s as if the producer Bresler “purposely wanted to sabotage Major Dundee” with this. Caliendo’s music is relatively conventional too but shows a much more sophisticated understanding of the relationship between screen and score. His treatment of the battle with the French is exciting, and earlier on there’s a terrific riding theme which, like so many in westerns, has a carefree levity that’s blackly at odds with the deadly mission it accompanies.

Add to all this a useful set of extras, and Arrow’s new Blu-ray set is a fine showcase for an imperfect but impactful movie which deserves to be watched as a fascinating revisionist western in its own right, not merely a notorious film maudit.

USA | 1965 | 122 MINUTES (THEATRICAL) • 136 MINUTES (2005 RESTORATION) | 2.39:1 | COLOUR | ENGLISH • FRENCH • SPANISH

director: Sam Peckinpah.

writers: Harry Julian Fink, Oscar Saul & Sam Peckinpah (story by Harry Julian Fink).

starring: Charlton Heston, Richard Harris, Jim Hutton, James Coburn, Michael Anderson Jr., Mario Adorf, Brock Peters & Senta Berger.