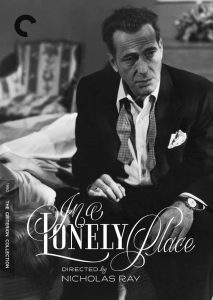

IN A LONELY PLACE (1950)

In a Lonely Place is a film about Hollywood. But, more precisely, it’s a film about Dixon Steele (Humphrey Bogart), a screenwriter whom we’re told is talented. He dismisses commercial film projects and rails against others in the industry who he sees as mere “popcorn salesmen”. It’s right to doubt his talents, though: not because we see any examples of his work, but because Dix is a conflicted man, hard to pin down. The film spends its time trying to work him out, as do the characters surrounding him. He can do one thing while his face tells us that he’s thinking and feeling something else entirely. This is no doubt aided by the conflict only Bogart could’ve brought to the character.

The film opens on the road with Dix driving through Hollywood at night. As he pulls up at a red light, an actress recognises him and her husband gets jealous. Dix steps out of the car to fight the man—the first sign he’s a violent figure who could never walk away from a chance to throw a punch. Later, love and violence will become intermingled during In a Lonely Place; Dix can’t always recognise the line between the two. He’s pulled into even darker territory when the girl he takes home one night is murdered after leaving his apartment. His history of violence and the fact that he was the last one to see her alive make him the prime suspect.

Luckily for Dix, Laurel Gray (Gloria Grahame), the young actress who lives in the apartment opposite, is on hand to offer him an alibi. He’s not off the hook, though. No one seems to really think that Dix is guilty; but no one seems convinced he’s innocent either. This contradiction is at the heart of the entire film. He might not have killed the girl, but Dix is not a man that anyone could call ‘innocent’ while keeping a straight face. Even Laurel—the woman who said she saw Dix, thereby giving him an alibi—finds it hard to be absolutely sure that he’s not the murderer.

Director Nicholas Ray’s compositions are striking on a number of occasions. He paints a picture of serene beauty when Dix and Laurel are in a piano bar together after falling in love. Despite the murder investigation, it’s as if there is nothing else going on in their lives. The smooth tracking shots and symmetrical framing tell us that they’re nothing more than two lovers spending a night out together. Ray then shatters the moment dramatically as Laurel, peering over Dix’s shoulder, spots the police officer trailing them; she sees something shocking that he doesn’t. All of a sudden, the cleanliness of the scene is dragged through the mud as Dix gets up and storms out, disrupting the singer at the piano in the process.

Director Nicholas Ray’s compositions are striking on a number of occasions. He paints a picture of serene beauty when Dix and Laurel are in a piano bar together after falling in love. Despite the murder investigation, it’s as if there is nothing else going on in their lives. The smooth tracking shots and symmetrical framing tell us that they’re nothing more than two lovers spending a night out together. Ray then shatters the moment dramatically as Laurel, peering over Dix’s shoulder, spots the police officer trailing them; she sees something shocking that he doesn’t. All of a sudden, the cleanliness of the scene is dragged through the mud as Dix gets up and storms out, disrupting the singer at the piano in the process.

At the start of the 1950s, it became common for Hollywood to analyse itself. Many films of the period idealised Hollywood—Singin’ in the Rain (1952) is the prime example. But In a Lonely Place is one of the films that took a more cynical swipe at the film industry. Everyone is fighting to stay relevant and stay employed. This means competing with others, fostering jealousies, and being completely self-interested. And one of the things that Dix finds hardest to deal with is the sycophants and hangers-on that Ray makes sure keep popping up throughout the film. The director manages to deconstruct Hollywood and the people populating it like no film ever had before.

Laurel is a curious character in the film. She isn’t dragged into the narrative against her will. She’s interested in Dix and implants herself in his life, but Ray never makes it clear whether she really did see Dix after the murdered girl left the apartment or not. Is she using the false alibi to get closer to Dix? Or did she really see him? If she did, Ray makes a point of not making this clear. This disconnect between what she saw and what she says she saw complicates the relationship and keeps the audience asking questions and doubting the motives and intentions of the characters.

The worries and paranoia of Laurel really come to the fore in the second part of the film. Her doubts over Dix are like an infection that takes hold and spreads. She can’t escape those doubts. In many ways, it recalls Hitchcock’s Suspicion (1941) in the second half as she becomes convinced her life is at risk, and she might not be entirely wrong. The line between the seemingly normal, placid man and the volatile, creative man, and their respective propensities for violence, is challenged in the film’s climax. This is also when we see the best of that conflict that Bogart plays so well. Can Dix be both basically decent and irredeemably violent at the same time? His body language seems to suggest so. And when Bogart even manages to look like a violent maniac when cutting a grapefruit, you can certainly understand Laurel’s dread and desire for escape.

writer: Edmund H. North & Andrew Solt (based on the novel by Dorothy B. Hughes).

starring: Humphrey Bogart, Gloria Grahame, Frank Lovejoy, Carl Benton Reid, Art Smith, Martha Stewart, Miss Jeff Donnell, Robert Warwick & Morris Ankrum.